Speaking of Kisses in Paradise: Burne-Jones's Friendship with Swinburne John Christian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simeon Solomon and the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili

VISIONS OF LOVE: SIMEON SOLOMON AND THE HYPNEROTOMACHIA POLIPHILI D.M.R. Bentley When Simeon Solomon met his “idol” Dante Gabriel Rossetti “early in 1858” and began working in Rossetti’s studio (Reynolds 7), he entered an artistic circle whose influence on his work was marked enough for it to be considered Pre-Raphaelite. Prior to meeting Rossetti, Solomon had made only a few drawings that show the influence of Pre-Raphaelitism, most notably Faust and Marguerite (1856) and Eight Scenes from the Story of David and Jonathan (1856), but he would soon become in all things Pre-Raphaelite. 1 Love (1858) and The Death of Sir Galahad While Taking a Portion of the Holy Grail Administered by Joseph of Arimathea (1857-59) are Pre- Raphaelite in manner and subject-matter, while Nathan Reproving Daniel (1859), Babylon Hath Been a Golden Cup (1859), Erinna Taken from Sappho (1865), The Bride, Bridegroom and Sad Love (1865), and other works of the late 1850s and early 1860s are Pre-Raphaelite in manner but bespeak, by turns, Solomon’s Jewish heritage and his increasingly forthright homo- sexuality . Portrait of Edward Burne-Jones (1859) is an idealized portrait of the artist as a clear-eyed visionary, and Dante’s First Meeting with Beatrice (1859-63) is an homage to Rossetti that is so extreme in its imitativeness as to verge on parody. But did Solomon’s admiration of Rossetti and Burne- Jones include knowledge of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (1499), the book that was arguably as important to the “New Renaissance ” phase (Allingham 140) of Pre-Raphaelitism as was the Morte D’Arthur to its Oxford phase – and, moreover, identified by Rossetti as “the old Italian book .. -

Victorian Paintings Anne-Florence Gillard-Estrada

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archive Ouverte en Sciences de l'Information et de la Communication Fantasied images of women: representations of myths of the golden apples in “classic” Victorian paintings Anne-Florence Gillard-Estrada To cite this version: Anne-Florence Gillard-Estrada. Fantasied images of women: representations of myths of the golden apples in “classic” Victorian paintings. Polysèmes, Société des amis d’inter-textes (SAIT), 2016, L’or et l’art, 10.4000/polysemes.860. hal-02092857 HAL Id: hal-02092857 https://hal-normandie-univ.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02092857 Submitted on 8 Apr 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Fantasied images of women: representations of myths of the golden apples in “classic” Victorian Paintings This article proposes to examine the treatment of Greek myths of the golden apples in paintings by late-Victorian artists then categorized in contemporary reception as “classical” or “classic.” These terms recur in many reviews published in periodicals.1 The artists concerned were trained in the academic and neoclassical Continental tradition, and they turned to Antiquity for their forms and subjects. -

Angeli, Helen Rossetti, Collector Angeli-Dennis Collection Ca.1803-1964 4 M of Textual Records

Helen (Rossetti) Angeli - Imogene Dennis Collection An inventory of the papers of the Rossetti family including Christina G. Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Michael Rossetti, as well as other persons who had a literary or personal connection with the Rossetti family In The Library of the University of British Columbia Special Collections Division Prepared by : George Brandak, September 1975 Jenn Roberts, June 2001 GENEOLOGICAL cw_T__O- THE ROssFTTl FAMILY Gaetano Polidori Dr . John Charlotte Frances Eliza Gabriele Rossetti Polidori Mary Lavinia Gabriele Charles Dante Rossetti Christina G. William M . Rossetti Maria Francesca (Dante Gabriel Rossetti) Rossetti Rossetti (did not marry) (did not marry) tr Elizabeth Bissal Lucy Madox Brown - Father. - Ford Madox Brown) i Brother - Oliver Madox Brown) Olive (Agresti) Helen (Angeli) Mary Arthur O l., v o-. Imogene Dennis Edward Dennis Table of Contents Collection Description . 1 Series Descriptions . .2 William Michael Rossetti . 2 Diaries . ...5 Manuscripts . .6 Financial Records . .7 Subject Files . ..7 Letters . 9 Miscellany . .15 Printed Material . 1 6 Christina Rossetti . .2 Manuscripts . .16 Letters . 16 Financial Records . .17 Interviews . ..17 Memorabilia . .17 Printed Material . 1 7 Dante Gabriel Rossetti . 2 Manuscripts . .17 Letters . 17 Notes . 24 Subject Files . .24 Documents . 25 Printed Material . 25 Miscellany . 25 Maria Francesca Rossetti . .. 2 Manuscripts . ...25 Letters . ... 26 Documents . 26 Miscellany . .... .26 Frances Mary Lavinia Rossetti . 2 Diaries . .26 Manuscripts . .26 Letters . 26 Financial Records . ..27 Memorabilia . .. 27 Miscellany . .27 Rossetti, Lucy Madox (Brown) . .2 Letters . 27 Notes . 28 Documents . 28 Rossetti, Antonio . .. 2 Letters . .. 28 Rossetti, Isabella Pietrocola (Cole) . ... 3 Letters . ... 28 Rossetti, Mary . .. 3 Letters . .. 29 Agresti, Olivia (Rossetti) . -

Pre-Raphaelite Sisters

Mariëlle Ekkelenkamp exhibition review of Pre-Raphaelite Sisters Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 1 (Spring 2020) Citation: Mariëlle Ekkelenkamp, exhibition review of “Pre-Raphaelite Sisters ,” Nineteenth- Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 1 (Spring 2020), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2020.19.1.13. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License Creative Commons License. Ekkelenkamp: Pre-Raphaelite Sisters Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 19, no. 1 (Spring 2020) Pre-Raphaelite Sisters National Portrait Gallery, London October 17, 2019–January 26, 2020 Catalogue: Jan Marsh and Peter Funnell, Pre-Raphaelite Sisters. London: National Portrait Gallery Publications, 2019. 207 pp.; 143 color illus.; bibliography; index. $45.58 (hardcover); $32.49 (paperback) ISBN: 9781855147270 ISBN: 1855147279 The first exhibition devoted exclusively to the contribution of women to the Pre-Raphaelite movement opened in the National Portrait Gallery in London in October. It sheds light on the role of twelve female models, muses, wives, poets, and artists active within the Pre- Raphaelite circle, which is revealed as much less of an exclusive “boys’ club.” The aim of the exhibition was to “redress the balance in showing just how engaged and central women were to the endeavor, as the subjects of the images themselves, but also in their production,” as stated on the back cover of the catalogue accompanying the exhibition. Although there have been previous exhibitions on the female artists associated with the movement, such as in Pre-Raphaelite Women Artists (Manchester City Art Galleries, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Southampton City Art Gallery, 1997–98), the broader scope of this exhibition counts models and relatives among the significant players within art production and distribution. -

BOOK REVIEW Modern Painters, Old Masters: the Art of Imitation From

Tessa Kilgarriff 126 BOOK REVIEW Modern Painters, Old Masters: The Art of Imitation from the Pre-Raphaelites to the First World War, by Elizabeth Prettejohn (London: Yale University Press, 2017). 288 pp. Hardback, £45. Reviewed by Tessa Kilgarriff (University of Bristol) Visual allusion and the transhistorical relationship between works of art and their viewers form the subject of Elizabeth Prettejohn’s illuminating study, Modern Painters, Old Masters. The author proposes that the much-maligned term ‘imitation’ most accurately describes the practice by which artists and viewers form relationships with their counterparts in other historical eras. The book argues that ‘imitation’ came in two distinguishing categories during the period from the 1848 founding of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood to the First World War: ‘competitive imitation’ (in which the artist attempts to transcend their predecessor) and ‘generous imitation’ (in which the artist faithfully copies the earlier model) (p. 15). In chapters on originality and imitation, on the influence of Jan van Eyck’s Portrait of (?) Giovanni Arnolfini and his Wife (1434), on the Pre-Raphaelites’ discovery of early Renaissance painters, on Frederic Leighton’s debts to Spanish painting, and on the tension between making art and looking at it, Prettejohn asks fourteen key questions. The formulation and clarity of these questions is explained by the origins of the book, namely Prettejohn’s Paul Mellon Lectures given at the National Gallery in London and at the Yale Center for British Art in 2011. Prettejohn’s incisive questions stringently rebuff the notion that the significance of visual allusions, or references, is limited to identification. -

PRE-RAPHAELITE STUNNERS at CHRISTIE’S in JUNE Works by Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Poynter and Leighton

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE : 20 A p r i l 2 0 1 5 PRE-RAPHAELITE STUNNERS AT CHRISTIE’S IN JUNE Works by Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Poynter and Leighton London – This summer, Christie’s London presents a stellar collection of Pre-Raphaelite and Victorian drawings and paintings – one of the very best collections in private hands with museum-quality works, some of which have not been seen for decades. Offered as part of the Victorian, Pre-Raphaelite & British Impressionist Art sale on 16 June 2015, this beautiful collection features 45 works and is expected to realise in the region of £2 million. Leading the collection is one of eight works by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), Beatrice: A Portrait of Jane Morris (estimate: £700,000-£1 million, illustrated above left). The collection presents the opportunity for both established and new collectors alike to acquire works at a wide range of price points with estimates ranging from £1,000 to £700,000. Harriet Drummond, International Head of British Drawings & Watercolours, Christie’s: “Christie's is delighted to be handling this important and breath-takingly beautiful collection of paintings and drawings brought together by a couple of anglophile art lovers, who combined their passion for the aesthetic of the Victorian Period with the discerning eye of the connoisseur collector. It is the art of this Victorian era celebrating beauty through its depiction of largely female figures, from the monumentality of ‘Desdemona’ to the intimacy of ‘Fanny Cornforth, asleep on a chaise-longue’ that so strongly influenced our idea of beauty today.” With the recent re-emergence of interest in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, led by Tate’s Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-Garde exhibition in 2012, this collection represents many of the ‘Stunners’ who inspired their paintings and made their work truly ‘romantic’, including eight beguiling works by Rossetti. -

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) Had Only Seven Members but Influenced Many Other Artists

1 • Of course, their patrons, largely the middle-class themselves form different groups and each member of the PRB appealed to different types of buyers but together they created a stronger brand. In fact, they differed from a boy band as they created works that were bought independently. As well as their overall PRB brand each created an individual brand (sub-cognitive branding) that convinced the buyer they were making a wise investment. • Millais could be trusted as he was a born artist, an honest Englishman and made an ARA in 1853 and later RA (and President just before he died). • Hunt could be trusted as an investment as he was serious, had religious convictions and worked hard at everything he did. • Rossetti was a typical unreliable Romantic image of the artist so buying one of his paintings was a wise investment as you were buying the work of a ‘real artist’. 2 • The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) had only seven members but influenced many other artists. • Those most closely associated with the PRB were Ford Madox Brown (who was seven years older), Elizabeth Siddal (who died in 1862) and Walter Deverell (who died in 1854). • Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris were about five years younger. They met at Oxford and were influenced by Rossetti. I will discuss them more fully when I cover the Arts & Crafts Movement. • There were many other artists influenced by the PRB including, • John Brett, who was influenced by John Ruskin, • Arthur Hughes, a successful artist best known for April Love, • Henry Wallis, an artist who is best known for The Death of Chatterton (1856) and The Stonebreaker (1858), • William Dyce, who influenced the Pre-Raphaelites and whose Pegwell Bay is untypical but the most Pre-Raphaelite in style of his works. -

Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Art and Design, 1848-1900 February 17, 2013 - May 19, 2013

Updated Wednesday, February 13, 2013 | 2:36:43 PM Last updated Wednesday, February 13, 2013 Updated Wednesday, February 13, 2013 | 2:36:43 PM National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Art and Design, 1848-1900 February 17, 2013 - May 19, 2013 Important: The images displayed on this page are for reference only and are not to be reproduced in any media. To obtain images and permissions for print or digital reproduction please provide your name, press affiliation and all other information as required (*) utilizing the order form at the end of this page. Digital images will be sent via e-mail. Please include a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned and your phone number so that we may contact you. Usage: Images are provided exclusively to the press, and only for purposes of publicity for the duration of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. All published images must be accompanied by the credit line provided and with copyright information, as noted. Ford Madox Brown The Seeds and Fruits of English Poetry, 1845-1853 oil on canvas 36 x 46 cm (14 3/16 x 18 1/8 in.) framed: 50 x 62.5 x 6.5 cm (19 11/16 x 24 5/8 x 2 9/16 in.) The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, Presented by Mrs. W.F.R. Weldon, 1920 William Holman Hunt The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, 1854-1860 oil on canvas 85.7 x 141 cm (33 3/4 x 55 1/2 in.) framed: 148 x 208 x 12 cm (58 1/4 x 81 7/8 x 4 3/4 in.) Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, Presented by Sir John T. -

Fanny Eaton: the 'Other' Pre-Raphaelite Model' Pre ~ R2.Phadite -Related Books , and Hope That These Will Be of Interest to You and Inspire You to Further Reading

which will continue. I know that many members are avid readers of Fanny Eaton: The 'Other' Pre-Raphaelite Model' Pre ~ R2.phadite -related books , and hope that these will be of interest to you and inspire you to further reading. If you are interested in writing reviews Robeno C. Ferrad for us, please get in touch with me or Ka.tja. This issue has bee n delayed due to personal circumstances,so I must offer speciaJ thanks to Sophie Clarke for her help in editing and p roo f~read in g izzie Siddall. Jane Morris. Annie Mine r. Maria Zamhaco. to en'able me to catch up! Anyone who has studied the Pre-Raphaelite paintings of Dante. G abriel RosS(:tti, William Holman Hunt, and Edward Serena Trrrwhridge I) - Burne~Jonc.s kno\VS well the names of these women. They were the stunners who populated their paintings, exuding sensual imagery and Advertisement personalized symbolism that generated for them and their collectors an introspeClive idea l of Victorian fem ininity. But these stunners also appear in art history today thanks to fe mi nism and gender snldies. Sensational . Avoncroft Museu m of Historic Buildings and scholnrly explorations of the lives and representations of these Avoncroft .. near Bromsgrove is an award-winning ~' women-written mostly by women, from Lucinda H awksley to G riselda Museum muS(: um that spans 700 years of life in the Pollock- have become more common in Pre·Raphaelite studies.2 Indeed, West Midlands. It is England's first open ~ air one arguably now needs to know more about the. -

Download This PDF File

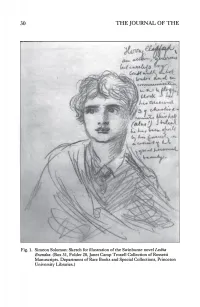

30 THE JOURNAL OF THE Fig. 1. Simeon Solomon: Sketch for illustration of the Swinburne novel Lesbla Brandon. (Box 31, Folder 20, Janet Gamp Troxell Collection of Rossetti Manuscripts. Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Libraries.) RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES 31 SWINBURNE AT PRINCETON BY MARGARET M. SHERRY Dr. Sherry is Reference Librarian and Archivist at Princeton University In the 1860s Swinburne was as engaged in writing fiction as in producing material for his first published volume of poetry, Poems and Ballads. The manuscript of his novel Lesbia Brandon, however, never went into print during his lifetime because Watts-Dunton disapproved of its incestuous subtext.1 The opening pages of the novel, which was published only posthumously by Randolph Hughes in 1952, give a detailed description of two pairs of eyes, those of brother and sister. Their resemblance to one another is so uncanny as to make both seem sexually ambiguous, if not entirely androgynous: "Either smiled with the same lips and looked straight with the same clear eyes."2 The frontispiece to this article, Figure 1, a sketch by the artist Simeon Solomon, gives us some idea of what the idealized beauty of the characters in this novel was to be. The second illustration, Figure 2, shows the younger brother Herbert, recovering from a flogging, sitting with his sister who has turned to look at him from where she sits at the piano. Herbert's teacher Denham, it is explained in the narrative, enjoys flogging his teenage pupil to punish Herbert's sister indirectly for being sexually inaccessible to him — she is already a married woman. -

Simeon Solomon Was a Pre-Raphaelite Artist Who Navigated the Modernity of Victorian

TRUTH TO (HIS) NATURE: JUDAISM IN THE ART OF SIMEON SOLOMON Karin Anger Abstract: Simeon Solomon was a Pre-Raphaelite artist who navigated the modernity of Victorian England to create works revolving around explicitly Jewish themes; often creating overtly Jewish images, highly unusual among the generally explicitly Christian movement. This article will deal with how Solomon constructed and dealt with his own identity as a Gay, Jewish man in the modern, and heavily Christian environment of mid-nineteenth century Victorian London. Using contemporary approaches to historicism, observation, and spirituality, his works deal with the complexities of his identity as Jewish and homosexual in a manner where neither was shameful, but rather, sources of inspiration. 1 Simeon Solomon was born in London to a middle class Ashkenazi Jewish family in 1840. Two of his older siblings, Abraham and Rebecca, were artists while his father worked as an embosser and had some training in design. Simeon was close to Rebecca; it is likely she introduced him to drawing and encouraged him in pursuing art.1 Simeon was admitted to the Royal Academy when he was fourteen and was quickly drawn to the Pre-Raphaelites. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood only lasted from1848-53 and had lost cohesion by the time Solomon was admitted to the Royal Academy in 1854. However, PRB art and ideas stuck around, meaning Solomon was exposed to their ideas and art through the PRB publication The Germ as well as displays of paintings and drawings by the movement during his time at the academy.2 Solomon had begun working in Pre-Raphaelite circles by the time he turned eighteen and became greatly admired by his colleges for his imagination and innovation.3 The Pre-Raphaelite ideas about art as fundamentally spiritual, that nature should be studied carefully, and honouring artistic tradition aside from what was deemed rote, were part of religious discourse in modern Britain. -

The Looking-Glass World: Mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite Painting 1850-1915

THE LOOKING-GLASS WORLD Mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite Painting, 1850-1915 TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I Claire Elizabeth Yearwood Ph.D. University of York History of Art October 2014 Abstract This dissertation examines the role of mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite painting as a significant motif that ultimately contributes to the on-going discussion surrounding the problematic PRB label. With varying stylistic objectives that often appear contradictory, as well as the disbandment of the original Brotherhood a few short years after it formed, defining ‘Pre-Raphaelite’ as a style remains an intriguing puzzle. In spite of recurring frequently in the works of the Pre-Raphaelites, particularly in those by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt, the mirror has not been thoroughly investigated before. Instead, the use of the mirror is typically mentioned briefly within the larger structure of analysis and most often referred to as a quotation of Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434) or as a symbol of vanity without giving further thought to the connotations of the mirror as a distinguishing mark of the movement. I argue for an analysis of the mirror both within the context of iconographic exchange between the original leaders and their later associates and followers, and also that of nineteenth- century glass production. The Pre-Raphaelite use of the mirror establishes a complex iconography that effectively remytholgises an industrial object, conflates contradictory elements of past and present, spiritual and physical, and contributes to a specific artistic dialogue between the disparate strands of the movement that anchors the problematic PRB label within a context of iconographic exchange.