Empirical Section of the Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Minutes

MM 23.06.2020 LISBURN & CASTLEREAGH CITY COUNCIL Minutes of the Remote Monthly Meeting of Council held on Tuesday, 23 June, 2020 at 5:32 pm PRESENT IN The Right Worshipful the Mayor CHAMBER: Councillor N Trimble Deputy Mayor Councillor Jenny Palmer Aldermen O Gawith, A Grehan, S Martin, S P Porter and J Tinsley Councillors N Anderson, H Legge, C McCready, U Mackin, T Mitchell, John Palmer PRESENT IN REMOTE Aldermen J Baird, W J Dillon MBE, D Drysdale, LOCATION: A G Ewart MBE, A Grehan and M Henderson MBE Councillors R T Beckett, R Carlin, S Carson, D J Craig, S Eastwood, A P Ewing, J Gallen, A Givan, A Gowan, M Gregg, M Guy, D Honeyford, S Hughes, J Laverty BEM, S Lee, S Lowry, J McCarthy, G McCleave, A McIntyre, R McLernon, S Skillen and A Swan IN ATTENDANCE: Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council Chief Executive Director of Environmental Services Director of Leisure and Community Wellbeing Director of Service Transformation Head of Communities Head of Human Resources & Organisation Development PCSP/Member Services Manager Member Services Officers IT Officer Mayor’s Chaplain Commencement of the Meeting Alderman S Martin and Councillor T Mitchell arrived to the meeting during this item of business (5.34 pm). Alderman S Martin and Councillor H Legge left the meeting during this item of business (5.36 pm). At the commencement of the meeting, The Right Worshipful the Mayor, Councillor N Trimble, welcomed those present to the remote meeting of Council, which was being live streamed to enable members of the public to hear and see the proceedings. -

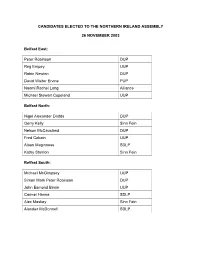

Peter Robinson DUP Reg Empey UUP Robin Newton DUP David Walter Ervine PUP Naomi Rachel Long Alliance Michael Stewart Copeland UUP

CANDIDATES ELECTED TO THE NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY 26 NOVEMBER 2003 Belfast East: Peter Robinson DUP Reg Empey UUP Robin Newton DUP David Walter Ervine PUP Naomi Rachel Long Alliance Michael Stewart Copeland UUP Belfast North: Nigel Alexander Dodds DUP Gerry Kelly Sinn Fein Nelson McCausland DUP Fred Cobain UUP Alban Maginness SDLP Kathy Stanton Sinn Fein Belfast South: Michael McGimpsey UUP Simon Mark Peter Robinson DUP John Esmond Birnie UUP Carmel Hanna SDLP Alex Maskey Sinn Fein Alasdair McDonnell SDLP Belfast West: Gerry Adams Sinn Fein Alex Atwood SDLP Bairbre de Brún Sinn Fein Fra McCann Sinn Fein Michael Ferguson Sinn Fein Diane Dodds DUP East Antrim: Roy Beggs UUP Sammy Wilson DUP Ken Robinson UUP Sean Neeson Alliance David William Hilditch DUP Thomas George Dawson DUP East Londonderry: Gregory Campbell DUP David McClarty UUP Francis Brolly Sinn Fein George Robinson DUP Norman Hillis UUP John Dallat SDLP Fermanagh and South Tyrone: Thomas Beatty (Tom) Elliott UUP Arlene Isobel Foster DUP* Tommy Gallagher SDLP Michelle Gildernew Sinn Fein Maurice Morrow DUP Hugh Thomas O’Reilly Sinn Fein * Elected as UUP candidate, became a member of the DUP with effect from 15 January 2004 Foyle: John Mark Durkan SDLP William Hay DUP Mitchel McLaughlin Sinn Fein Mary Bradley SDLP Pat Ramsey SDLP Mary Nelis Sinn Fein Lagan Valley: Jeffrey Mark Donaldson DUP* Edwin Cecil Poots DUP Billy Bell UUP Seamus Anthony Close Alliance Patricia Lewsley SDLP Norah Jeanette Beare DUP* * Elected as UUP candidate, became a member of the DUP with effect from -

OFFICIAL REPORT (Hansard)

OFFICIAL REPORT (Hansard) Vol u m e 2 (15 February 1999 to 15 July 1999) BELFAST: THE STATIONERY OFFICE LTD £70.00 © Copyright The New Northern Ireland Assembly. Produced and published in Northern Ireland on behalf of the Northern Ireland Assembly by the The Stationery Office Ltd, which is responsible for printing and publishing Northern Ireland Assembly publications. ISBN 0 339 80001 1 ASSEMBLY MEMBERS (A = Alliance Party; NIUP = Northern Ireland Unionist Party; NIWC = Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition; PUP = Progressive Unionist Party; SDLP = Social Democratic and Labour Party; SF = Sinn Fein; DUP = Ulster Democratic Unionist Party; UKUP = United Kingdom Unionist Party; UUP = Ulster Unionist Party; UUAP = United Unionist Assembly Party) Adams, Gerry (SF) (West Belfast) Kennedy, Danny (UUP) (Newry and Armagh) Adamson, Ian (UUP) (East Belfast) Leslie, James (UUP) (North Antrim) Agnew, Fraser (UUAP) (North Belfast) Lewsley, Patricia (SDLP) (Lagan Valley) Alderdice of Knock, The Lord (Initial Presiding Officer) Maginness, Alban (SDLP) (North Belfast) Armitage, Pauline (UUP) (East Londonderry) Mallon, Seamus (SDLP) (Newry and Armagh) Armstrong, Billy (UUP) (Mid Ulster) Maskey, Alex (SF) (West Belfast) Attwood, Alex (SDLP) (West Belfast) McCarthy, Kieran (A) (Strangford) Beggs, Roy (UUP) (East Antrim) McCartney, Robert (UKUP) (North Down) Bell, Billy (UUP) (Lagan Valley) McClarty, David (UUP) (East Londonderry) Bell, Eileen (A) (North Down) McCrea, Rev William (DUP) (Mid Ulster) Benson, Tom (UUP) (Strangford) McClelland, Donovan (SDLP) (South -

Leverhulme-Funded Monitoring Programme

Leverhulme-funded monitoring programme Northern Ireland report 2 February 2000 Contents Summary Robin Wilson 3 Getting going Rick Wilford 4 The media Liz Fawcett 17 Public attitudes and identity (Nil return) Finance Paul Gorecki 19 Political parties and elections (Nil return) Intergovernmental relations Graham Walker/ 21 Robin Wilson Relations with the EU Elizabeth Meehan 26 Public policies Robin Wilson 30 Into suspension Robin Wilson 32 2 Summary The last monitoring report from Northern Ireland was unique in the tripartite study because only in Northern Ireland had powers not been transferred to the new devolved institutions. This, second, report is also unique in that, whatever crises the Scottish and Welsh executives have experienced, the Northern Ireland Executive Committee has, within the space of a little over two months, not only come but also, for the moment at least, gone. If ever the point needed proving that the region is, constitutionally and politically, sui generis, this latest episode on the roller coaster blandly described as the Northern Ireland ‘peace process’ surely underscored it. This report is therefore, in its tenor, once more a victim of the hypertrophy of politics in Northern Ireland. Relatively little emphasis is given to the ‘normal’ concerns addressed elsewhere, compared with the iterative reworking of the already well-worn themes in the political discourse—of decommissioning and devolution. As a result, what would come under the headings of the devolved government and the assembly/parliament in the other reports here focuses more on the establishment of the institutions than on their substantive work. And there is inevitably a long exegesis of the process leading to their demise. -

The Northern Ireland Assembly

No. 1/99 NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS MONDAY 6 DECEMBER 1999 The Assembly met at 10.30 am, the Presiding Officer in the Chair 1. Personal Prayer or Meditation 1.1 Members observed two minutes’ silence. 2. Statutory Committee Business 2.1 Motion Proposed: That this Assembly confirms ‘MLA’ as designatory letters for Assembly Members. [Mr F Cobain] [Mr D Haughey] After debate, the Question being put, the Motion was carried without division. 2.2 Motion Proposed: After Standing Order 57 insert a new Standing Order: Standing Committee on European Affairs 1. There shall be a Standing Committee of the Assembly to be known as the Standing Committee on European Affairs. 2. It shall consider and review on an ongoing basis: (a) matters referred to it in relation to European Union issues; and (b) any other related matter or matters determined by the Assembly. 199 3. The Committee shall have powers to call for persons and papers. 4. The procedures of the Committee shall be such as the Committee shall determine. [Mr F Cobain] [Mr D Haughey] After debate, the Question being put, the Motion was carried without division. 2.3 Motion Proposed: After Standing Order 57 insert a new Standing Order: Committee on Equality, Human Rights and Community Relations 1. There shall be a Standing Committee of the Assembly to be known as the Equality, Human Rights and Community Relations Committee. 2. It shall consider and review on an ongoing basis: (a) matters referred to it in relation to Equality, Human Rights and Community Relations; and (b) any other related matter or matters determined by the Assembly. -

Northern Ireland Assembly

NORTHERN IRELAND Mr Speaker: I thank the Member for her point of order. I not only encourage Whips, but all Members, to ASSEMBLY visit the Business Office to see the procedure for selection of questions to the House. I hope that more Members will do so and will, therefore, have a better understanding of how questions to Ministers are selected. Tuesday 30 September 2008 The Assembly met at 10.30 am (Mr Speaker in the Chair). Members observed two minutes’ silence. ASSEMBLY BUSINESS Mr Lunn: On a point of order, Mr Speaker. Before the start of Question Time last Monday, Basil McCrea made a point of order about the selection of questions for Question Time. Correctly, you said that that issue was not the business of the Speaker’s Office. In his comments, Mr Basil McCrea queried the integrity of Assembly staff. He said: “We have been assured that the selection of questions is a random process. Clearly, it cannot be”. — [Official Report, Vol 33, No 3, p108, col 2]. He also said: “four, five or six of the first six questions are regularly asked by the party to which the responding Minister belongs. There is something not right. I am not saying that something is wrong, but something is not right.” — [Official Report, Vol 33, No 3, p108, col 2]. Assembly staff will be concerned about those comments. Did Mr Basil McCrea breach any of the rules of the House when he made those comments? Would it be appropriate to give him the opportunity in the House to retract his comments? If he was not accusing Assembly staff, who was he accusing? Mr Speaker: I accept the Member’s comments, and there are several issues to address. -

Download Minutes

AM 07.06.2021 LISBURN & CASTLEREAGH CITY COUNCIL Minutes of the Annual Meeting of Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council held remotely and in the Council Chamber, Island Civic Centre, The Island, Lisburn, on Monday 7 June, 2021 at 12.02 pm PRESENT IN The Right Worshipful the Mayor COUNCIL CHAMBER Councillor N Trimble (Outgoing) Alderman S Martin (Incoming) Deputy Mayor Councillor Jenny Palmer (Outgoing) Councillor T Mitchell (Incoming) Aldermen J Baird, M Henderson MBE, O Gawith and J Tinsley Councillors R T Beckett, R Carlin, A P Ewing, J Laverty BEM, S Lee, H Legge, S Lowry, J McCarthy, C McCready, John Palmer, S Skillen and A Swan PRESENT IN A Aldermen D Drysdale, A G Ewart MBE and S P Porter REMOTE LOCATION Councillors N Anderson, S Carson, D J Craig, S Eastwood, J Gallen, A Givan, A Gowan, M Gregg, M Guy, D Honeyford, S Hughes, G McCleave, A McIntyre, R McLernon and U Mackin IN ATTENDANCE IN Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council COUNCIL CHAMBER Chief Executive Acting PSCP/Member Services Manager Member Services Officers Technician IT Officer IN ATTENDANCE IN Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council REMOTE LOCATION Director of Environmental Services Director of Finance and Corporate Services Director of Leisure and Community Wellbeing Director of Service Transformation The Very Reverend Sam Wright Commencement of Meeting At the request of Alderman M Henderson, The Right Worshipful the Mayor (Outgoing), Councillor N Trimble, agreed not to enforce Standing Order 19.6, which required a Member to stand when addressing the meeting, on the basis of medical grounds. 471 AM 07.06.2021 The Right Worshipful the Mayor (Outgoing) welcomed those present to the Annual Meeting of Council which was being live-streamed to enable members of the public to both hear and see the proceedings. -

Local Government Studies Article

This article was downloaded by: [Swets Content Distribution] On: 19 December 2009 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 912280237] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Local Government Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713673447 The Politics of Local Government Reform in Northern Ireland Colin Knox a a School of Policy Studies, University of Ulster, Newtownabbey, Northern Ireland To cite this Article Knox, Colin(2009) 'The Politics of Local Government Reform in Northern Ireland', Local Government Studies, 35: 4, 435 — 455 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/03003930902992691 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03003930902992691 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Autism Debate 2002

Northern Ireland Assembly Tuesday 23 April 2002 (continued) Mrs Courtney mentioned the number of hospitals in her constituency that, at different times, have experienced difficulties with the provision of equipment and services. She too acknowledged the vital role that organisations such as "Friends of Hospitals" provide in meeting the needs of the area that she represents. Rev Robert Coulter has given the reasons why the Ulster Unionist Party cannot support the amendment. We would like "Friends of Hospitals" to be able to operate with total freedom to meet the needs of the hospitals that they represent, and, in collecting for their hospital, contribute to the needs of that hospital and help it to develop the services required in their area. Ms Ramsey: Will the Member give way? Mr Hamilton: No. Therefore, we urge Members to reject the amendment, because it does not provide fully for that. This has been a timely debate, and it is a worthy motion. The proposer highlighted its success in other parts of the UK. The Department should consider seriously the motion. I, therefore, urge Members to reject the amendment and support the motion. Question put, That the amendment be made. The Assembly divided: Ayes 28; Noes 36. Ayes Alex Attwood, P J Bradley, Joe Byrne, Annie Courtney, John Dallat, Bairbre de Brún, Pat Doherty, Mark Durkan, David Ervine, Sean Farren, Tommy Gallagher, Carmel Hanna, Billy Hutchinson, John Kelly, Patricia Lewsley, Alban Maginness, Alex Maskey, Alasdair McDonnell, Gerry McHugh, Eugene McMenamin, Pat McNamee, Monica McWilliams, Conor Murphy, Mick Murphy, Mary Nelis, Eamonn ONeill, Sue Ramsey, John Tierney.