Juan Rosai, ‘Master of the Neoplastic Universe’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sleuths BEHIND the Scenes for PATHOLOGISTS, the UNUSUAL IS the USUAL

ON THE COVER sleuths BEHIND THE scenes FOR PATHOLOGISTS, THE UNUSUAL IS THE USUAL. BY HOWARD BELL ennifer Boland’s path to pathology began during her sec- ond year of medical school at Washington University in St. Louis. Boland would take study breaks by looking at Jspecimen slides and images, learning to identify them. “Pathology is a visual science. I found it more enjoyable than memorizing notes,” she recalls. After a surgical pathology elective during her clinical rotations, she was hooked. “In medicine it can be hard to find the field you love,” says Boland, who is now a pathologist at Mayo Clinic. “I was lucky enough to find it.” Boland began practicing at Mayo three years ago, after com- pleting a pathology residency as well as pulmonary and surgical pathology fellowships there. She specializes in pulmonary and bone and soft-tissue pathology. Her particular expertise is in lung and chest sarcomas. “They’re a rare and interesting set of tumors,” she says. “Very few are diagnosed in this country each year.” Like many Mayo pathologists, she spends about half her time evaluating specimens from around the world for Mayo Medical Laboratories and the other half evaluating specimens from Mayo patients. Depending on case complexity, she evaluates around 25 to 50 specimens each day. “I like the mystery-solving of pathol- ogy,” she says. Boland is one of 332 pathologists who practice in Minnesota, according to the Minnesota Board of Medical Practice. Often thought of as either white-coated geeks hunched over microscopes or sexy swashbucklers who spend more time solving crimes than analyzing specimens (thanks to TV), pathologists 20 | MINNESOTA MEDICINE | OCTOBER 2014 ON THE COVER OCTOBER 2014 | MINNESOTA MEDICINE | 21 ON THE COVER are sleuths working behind the scenes to ogy, Boland says, adding that many don’t years for neuropathology). -

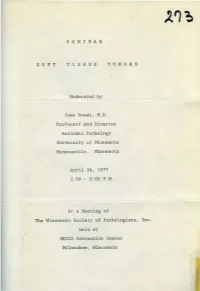

S E M I N a R TISSUE Juan Rosai, M.D. Professor and Director

' S E M I N A R S 0 F T TISSUE T U M 0 R S Moderat~d by Juan Rosai , M.D. Professor and Director Anatomic Pathology University of t1innesota Minneapolis, Minnesota April 16, 1977 2:00~ - 5:00P.M. At a Meeting of The Wisconsin Society of Pathologists, Inc. held at ~mCCA Convention Center Milwaukee, Wisconsin • Contributors : Harilyn O'Brien, 11.0. Rocco Latorraca, H.D. 'l'rinity MellOrial Hospital Cudahy, Wisconsin This lS·year old girl had been aware of some pain and discomfort on the lateral aspect of he·r l eft thigh for several years . There was no recollection of what may have started this pain. There was no ~~own injur.y OJ: £all. About a year bef ore her hospitaliza.tion, her .pain and discomfort increased w~th dancing and increased activit y. The area involved was the outer aspect of the left t high just bel01~ the great~r t rochanter. About four months prior to admission, a small swelling was ~oted. The x-rays of the extremity were not available. The consultant' s report described an i ll-defined soft tissue swelling with some speckling in the tissues, indicative of calcification. There was no bone involve ment. Pelvis and chest x- rays were negative. The mass was excised. It was oval, encapsulated,, lobul ar and creamy tan to light red v1ith vascular markings . Lab Data - normal. • ~ISP-2-77 Contributor: Mary Fernandez, 11 .0. Lutheran Hospital of Milwaukee Milwaukee, Wisconsin . The hist ory is that of a 39 year old white male school teacher who first noticed a tumor beneath t he left eye in January of 1976. -

Siegal, G.P. Curriculum Vitae Page 2 FACULTY CURRICULUM VITAE UNIVERSITY of ALABAMA at BIRMINGHAM SCHOOL of MEDICINE

Siegal, G.P. Curriculum Vitae Page 2 FACULTY CURRICULUM VITAE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA AT BIRMINGHAM SCHOOL OF MEDICINE Date: June 14, 2017 GENE PHILIP SIEGAL 4927 Cold Harbor Drive Born: - Bronx, NY Mountain Brook, AL 35223 Married - Sandra H. Siegal, B.S., M.S. Office - (205) 934-6608 Two Adult Daughters - Gail and Rebecca Fax - (205) 975-7284 Home - (205) 956-6199 CITIZENSHIP: United States of America Email - [email protected] EDUCATION Degree Major Institution Dates of Attendance ---- Academic Plainview High School 9/63 - 6/66 Regents Diploma Plainview, NY B.A. Biology Adelphi University 9/66 - 6/70 Garden City, NY M.D. ---- University of Louisville 9/70 - 5/74 School of Medicine Louisville, KY Ph.D. Experimental University of Minnesota 7/75 - 9/79 Pathology Minneapolis, MN Certificate in Management Univ. of North Carolina 8/88 - 11/88 Hospital Institute Kenan-Flagler Sch. of Bus. Admin. Management Chapel Hill, NC Certificate UAB Health Univ. of AL at Birmingham 9/99 - 1/00 Care Leadership School of Health Rel. Prof. &. Institute School of Business Admin. EXPERIENCE AND TRAINING Extern in Pediatrics Long Island Jewish-North Shore Summer, 1972 University Health System (A. Einstein College of Medicine) Senior Medical School University of Louisville Fall/Winter, 1973 Tutorials Department of Pathology Anatomic Pathology (W.M. Christopherson), Electron Microscopy (G.R. Schrodt), Pediatric Pathology (D.R. Kmetz) Intern in Pathology Mayo Graduate School of Medicine 7/74 - 6/75 Mayo Clinic College of Medicine Mayo Clinic/Foundation Resident in Pathology Mayo Graduate School of Medicine 7/75 - 6/76 Mayo Clinic College of Medicine Siegal, G.P. -

Presentation Transcript

Good morning everybody. I'm Juan Rosai, or better the digital image of Juan Rosai whose body is many miles away from here. I wish I was here with my friends, but circumstances beyond my control prevent me from doing this. You will have to do with my image and the images that you will see in a minute in this screen. Let me first thank Dr. Rachel Factor the director of the course for the kind invitation and Dr. Mary Bronner the chief of surgical pathology. The task that they gave me for the meeting was that of discussing the intraductal proliferative lesions of the breast, and that is what I'm going to do. But a disclaimer first. If you expect me to show you to go over the minute criteria that I use to distinguish one proliferative type of breast tissue from the other, you will be disappointed. Those you can find in many textbooks and monographs, some of which I will show. I'm going to discuss instead this field from a holistic point of view, from a historic point of view, describing how the changes and the constant change over the years, who are the main players, what influence they have in these changes, where we are now, and what can we expect in the future. Well these lesions have been around for a long time and the various names that have been given to them is a good reflection on how difficult, how mysterious, how challenging they were to the pathologists who examined them. -

Engage to the Power of E PATHOLOGY’S Evolution

ENGAGE TO THE POWER OF e PATHOLOGY’S eVOLUTION Healthcare organizations are focused on improving patient care by making significant investments in health information technology for the creation of patients’ electronic health records (EHR). The need to assemble patient data electronically exists in all areas, including Pathology. TODAY, PATHOLOGY IMPACTS AS MUCH AS 70% OF ALL PERSONALIZED MEDICINE INTEGRATION OF ALL PATIENT HEALTHCARE INFORMATION: IMAGES & DIAGNOSTICS DECISIONS AFFECTING 2016 THERAPEUTICS DIAGNOSIS AND PRECISION PATHOLOGY IS INSTRUMENTAL TO TREAT CANCERS AND DISEASES WITH TREATMENT. NEW AND TARGETED DRUGS As the range of Pathology services has evolved 2012 PrognoSTIC so has Digital Pathology. Now more than ever, CANCERS AND OTHER DISEASES NOW Pathologists require easy and immediate access REQUIRE MORE PRECISION USING to slide images and findings. And, they need to be BIOMARKERS OR ONE OF THE “omics” available to monitor treatment response and to provide expert opinions. TRADITIONAL PATHOLOGY TRADITIONAL PATHOLOGY ALONE IS NO The rules of engagement have changed; it’s time LONGER SUFFICIENT TO MEET TODAy’s to equip Pathologists to participate more fully CHANGING HEALTHCARE NEEDS with the entire healthcare team. With Aperio ePathology Solutions, organizations can optimize their pathology operations for transparency, consistency and efficiency to support patient care, personalized medicine and research. ENGAGE, EVALUATE AND EXCEL APERIO® ePATHOLOGY SOLUTIONS From the moment glass slides are digitized to eSlides, Aperio ePathology -

CURRICULUM-VITAE Saul Suster, M.D

CURRICULUM-VITAE Saul Suster, M.D. PERSONAL DATA: Home Address: N14 W30351 Willow Hill Rd. Delafield, WI 53018 Work Address: Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine The Medical College of Wisconsin Dynacare Lab. Bldg., Room 226 9200 West Wisconsin Avenue Milwaukee, WI 53226 Home phone: (262) 361-4092 Work phone: (414) 805-6968 FAX number: (414) 805-6980 Electronic mail: [email protected] Current Position Professor and Chairman and Title: Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine The Medical College of Wisconsin Milwaukee, Wisconsin Medical Director Dynacare Laboratories Milwaukee, Wisconsin Director, Translational Research and Tissue Banking Divison, Department of Pathology, Medical College of Wisconsin. Date of Birth: December 29, 1950 Place of Birth: Guayaquil, Ecuador Marital Status: Married, two children Citizenship: United States Citizen 8/1/13 Page 1 PREVIOUS PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS: Vice-Chairman and Director of Anatomic Pathology Services, Department of Pathology, The Ohio State University Hospitals and the Arthur G. James Cancer Center and Solove Research Institue, Columbus, OH, 1998-2007. Director of Surgical Pathology, Immunohistochemistry and Electron Microscopy, Mount Sinai Medical Center of Greater Miami, Miami Beach, FL, Clinical Professor of Pathology, University of Miami School of Medicine, 1990-1997. PROFESSIONAL CERTIFICATIONS & LICENSURE: ISRAELI BOARD OF PATHOLOGY: Certificate of passing written examination for pathology of the Scientific Council of the Israel Medical Association, Jerusalem, Israel, July 1, 1982. VISA QUALIFYING EXAMINATION: Certificate of passing Basic Science and Clinical Science components, November 1983. ECFMG CERTIFICATE: Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates; certificate No. 301-114-5, February 15, 1984. FEDERAL LICENSING EXAMINATION: FLEX candidate No. 001096; certificate of passing components 1 and 2, September 1987. -

Dear Esteemed Colleagues and Friends: Together with the Previous Document Prepared by Charter President Henry A

Dear Esteemed Colleagues and Friends: Together with the previous document prepared by Charter President Henry A. Azar, I have thought useful and indeed inspiring to organize a complete list of past Meetings and Officers of the History of Pathology Society. The Society was created on March 22, 1996 by a group of 40 charter members from all corners of the world. Congratulations and wishes of future success are thus due to all distinguished Members and Officers on this 20th anniversary of our Society! (Santo V. Nicosia, Secretary-Treasurer) HISTORY OF PATHOLOGY SOCIETY LIST OF COMPANION MEETINGS - 1997-2016 (List compiled by Santo V. Nicosia, Secretary-Treasurer) 1. March 2, 1997 (Orlando, FL) “The Beginnings of Modern Pathology” Moderator: William H. Hartmann Speakers: Santo V. Nicosia: Giovanni Battista Morgagni and the Beginnings of Anatomic Pathology Christian Nezeloff: Rene` Th. H. Laennec- The Birth of Clinico-Anatomic Model Darryl Carter: Origins of Surgical Pathology at the Johns Hopkins Hospital 2. March 1, 1998 (Boston, MA) “The Emergence of American Surgical Pathology” Moderator: Robert H. Young Speakers: Henry A. Azar: Arthur Purdy Stout Leopold G. Koss: Fred Waldorf Stewart Thomas A. Seemayer: Professor Pierre Masson Juan Rosai: Lauren V. Ackerman 3. March 21, 1999 (San Francisco, CA) “Thomas Hodgkin: The Man and his Disease” Moderator: Peter J. Dawson Speakers: Peter Dawson: The Original Illustrations of Hodgkin’s Disease Louis Rosenfeld: Thomas Hodgkin: Social Activist Clive R. Taylor: The Evolution of Hodgkin’s Disease 4. May 18, 2000 (Bethesda, MD) “How Laboratory Medicine Became a Clinical Specialty” Moderator: Ann M. Nelson Speakers: Dale Smith: From Physician Technician to Medical Specialist – The Origins of Clinical Pathology Fred Meyer: An Ecologic Succession: Differential Models of Microbiology William Gardner and Aaron DeGroft: Laboratorians Commemorated in Stamps 5. -

Frederick T. Kraus, MD: an Interview with Thomas M

International Journal of Gynecological Pathology 35:482–496, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore r 2016 International Society of Gynecological Pathologists Other Frederick T. Kraus, MD: An Interview With Thomas M. Ulbright Frederick T. Kraus, M.D. and Thomas M. Ulbright, M.D. Key Words: FT Kraus—LV Ackerman—Surgical pathology—History. Frederick T. Kraus, Fred to his many friends, is a institutions. He developed an extensive consultation still-active pathologist at the age of 86 yr with a practice in the St. Louis area, not only for lesions special interest in gynecologic and placental pathol- related to gynecologic pathology but also covering ogy. He has practiced his entire career in the environs numerous areas of surgical pathology. His diagnostic of St. Louis, Missouri, both at Washington Univer- acumen and understated, modest demeanor made sity and at 2 large private hospitals. For those of my him a sought-after advisor for members of that generation, his book, Gynecologic Pathology, pub- pathology community but his influence has been felt lished in 1967, clarified what at that time was an much further afield. I first became acquainted with especially confusing area of pathology that had Fred when he willingly gave teaching conferences to hitherto been mostly in the province of gynecologists residents in pathology at Washington University, with limited experience in pathology. It remains a fine probably about 1976. These were challenging affairs, example of lucidity and clinicopathologic correlation. requiring not only knowledge of the morphology of Early in his career Fred worked as a faculty member various lesions but their clinical significance and at Washington University in the illustrious Division differential diagnosis. -

SEMINAR on TUMORS of the THYHUS CASE I DIAGNOSIS S.P. I Ttl,Ymoma, Classical, Benign R75-1514 2 Thymoma, Lymphocytic Predominanc

SEMINAR ON TUMORS OF THE THYHUS CASE i DIAGNOSIS S.P. I 1 Ttl,Ymoma, classical, benign R75-1514 2 Thymoma, lymphocytic predominance UH75-2533 3 Mal ignant t hymoma, metastatic R76-91 4 t~ a l igna n t t hymoma in a chi ld R76 -1369 5 t~ a 1igna nt thymoma , sarcomatoid R76-1363 6 Hodgk in's disease of thymus UH74- 4:2.1.7. 7 Halignant lymphoma, lymphoblastic, of thymus R76-1219 8 lola 1i gnant lymphoma vs. thymoma R76-355 9 Yolk sac tumor of mediastinum R76-231 10 Carcinoid tumor of thymus R76-1291 SEMINAR ON PATHOLOGY OF THE THYMUS Or. Juan Rosai ' Professor of Pathology and Director of Anatomic Pathology University of Minnesota Medical School Minneapolis, Minnesota CASE 1 - (R75-1514; Courtesy of Dr . Thomas R. Hal l in, MethodistHospital, l~inn eapoli s). 66-year-old male with history of myasthenia gravis for 6 years, whi ch appeared fo 11 o~1i ng an appendectomy. The main symptoms were di pl opi a, bilateral ptosis and difficulty in chewi ng. A recent chest x-ray s ho1~ed a 6cm. mass located in the anterior mediastinum. Labora tory tests were normal. A thoracotomy was performed and an encapsulated tumor was found. The posterior aspect of this tumor was adherent to the pericardium. There were also fibrous adhesions with left lung and chest w~ll. CASE :2- (#UH75-2533): 25-year-old female 1~ith a history of chronic cough and corticaria. Chest x-rays showed a mass in the anterior mediastinum, which was removed in its entirety. -

Word from the President Prof. M. Wells

Number 4 – Winter 2009-2010 particularly Bulgaria and Romania; both Table of Contents: countries have a small ageing workforce with little succession planning. Word from the President Prof. M, Wells p.1, p. 2 However, for me, the most significant Important Announcement, Intercongress Meeting of the ESP factor acting to the severe detriment of in Krakow p.2 cellular pathology is the differential What’s New? Minimal Lymph Node Involvement and the salaries (even in the state sector) Outcome of Breast Cancer, p.3, p.4 between pathologists and, for example, Message from Prof. M. Santucci, President of the ECP of the surgeons. This must act as a real disincentive to young doctors to consider ESP in Florence 2009, p.5, p.6 cellular pathology as a career; The Pathologist- interview with Prof. F. Bosman by Prof. M. pathologists are not second class Marichal,p.7,p.8 citizens and, in my view, this matter NEW: News from the ESP Working Groups needs to be addressed urgently at the Nephropathology WG, Message from the Chairman Prof. M. highest level in Europe. Mihatsch, p. 9. Announcements, p.10, p.11, p.12, p.13, p.14, p.15 Over the weekend of 30 October – 1 rd Job Offers, p.16, p.17 November I attended the 3 Hellenic Jordanian Congress of Pathology in Cyprus, organised by Professor Niki Word from the President Agnantis under the auspices of the ESP. Prof. M. Wells I gave a keynote lecture and addressed I am writing this at our Brussels office the congress at its gala dinner. -

Juan Rosai, MD RE

MEMO TO: FDA’s Hematology and Pathology Devices Panel FROM: Juan Rosai, M.D. RE: October 22-23rd 2009 FDA Meeting on the regulatory future for the advancement of Digital Pathology devices to be used to be used as diagnostic instruments to assist pathologists in the evaluation of histopathology tissue samples, in a manner equivalent to the traditional light microscope. DATE OF THIS MEMO: September 18, 2009 Dear Sirs: My name is Juan Rosai. I am an M.D. and a senior surgical pathologist with a long experience in American academic (and lately private) medicine. This includes pathology training under Dr. Lauren Ackerman at Washington University in St Louis, Director of Anatomic Pathology at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis (10 years), Director of Anatomic Pathology at Yale University in New Haven (6 years), Chairman of the Pathology Department at Memorial Sloan- Kettering Cancer Center in New York (10 years), Chairman of the Pathology Department of the National Cancer Institute in Milàn, Italy (5 years), and currently holding the dual position of Senior Diagnostic Pathologist at Genzyme-Genetics, New York, and the directorship of the International Center for Pathology Consultations at the Centro Diagnostico Italiano (Italian Diagnostic Center) in Milàn, Italy. I am the author of the textbook “Rosai and Ackerman’s Surgical Pathology” now in its ninth edition, and widely regarded the premier publication in the field. I have also been the Edtor- in-Chief of the Third Series A.F.I.P. Atlas of Tumor Pathology and senior author of two of the fascicles of that Series (Tumors of Thymus-2nd series; Tumors of Thyroid gland-Third Series). -

Success Story: Secondslide™ Streamlines the Consultation Process, Improves Turnaround Time

Success Story: SecondSlide™ Streamlines the Consultation Process, Improves Turnaround Time Challenge: Turnaround time for a consultation can be extremely slow—requiring days or even weeks for the transport of glass slides—particularly in cases where the consulting pathologist lives in another country and slides are held up in customs. Solution: SecondSlide™ digital slide sharing service was utilized, making it easy to share digital slides regardless of location, streamlining the consultation process and improving the experience for pathologists. Background & Challenges Solution Pathology tissue specimens are typically shared by shipping Dr. Rosai, Dr. Arias-Stella, and Dr. Franco expressed their the glass microscope slide between locations. Shipping glass interest in participating in a pilot study to test and measure the slides to another pathologist is a cumbersome task that involves effectiveness and efficiency of using a digital slide sharing service a significant amount of administrative labor and often results for obtaining a consultation without having to ship the glass. in time delays. Shipping glass slides internationally imposes The pilot leveraged SecondSlide, a digital slide sharing service for even greater challenges as customs laws often prohibit or slow sharing pathology slides domestically or internationally, to achieve down importation and/or exportation of tissue. Furthermore, its objectives. The objectives of the pilot included the following: glass slides can be in only one location at a time, which makes it difficult for two pathologists to engage in productive discussion without traveling to meet at the same location to view the glass slide under a multi-headed microscope. Juan Rosai, M.D., world-renowned expert and consultant in surgical pathology, is familiar with these challenges.