A Performance Guide to Three Representative Electroacoustic Piano Works by Mario Davidovsky, Dan Vanhassel and Peter Van Zandt Lane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report to the Friends of Music

Summer, 2020 Dear Friends of the Music Department, The 2019-20 academic year has been like no other. After a vibrant fall semester featur- ing two concerts by the Parker Quartet, the opening of the innovative Harvard ArtLab featuring performances by our faculty and students, an exciting array of courses and our inaugural department-wide throwdown–an informal sharing of performance projects by students and faculty–we began the second semester with great optimism. Meredith Monk arrived for her Fromm Professorship, Pedro Memelsdorff came to work with the Univer- sity Choir as the Christoph Wolff Scholar, Esperanza Spalding and Carolyn Abbate began co-teaching an opera development workshop about Wayne Shorter’s Iphigenia, and Vijay Iyer planned a spectacular set of Fromm Players concerts and a symposium called Black Speculative Musicalities. And then the world changed. Harvard announced on March 10, 2020 that due to COVID-19, virtual teaching would begin after spring break and the undergraduates were being sent home. We had to can- cel all subsequent spring events and radically revise our teaching by learning to conduct classes over Zoom. Our faculty, staff, and students pulled together admirably to address the changed landscape. The opera workshop (Music 187r) continued virtually; students in Vijay Iyer’s Advanced Ensemble Workshop (Music 171) created an album of original mu- sic, “Mixtape,” that is available on Bandcamp; Meredith Monk created a video of students in her choral class performing her work in progress, Fields/Clouds, and Andy Clark created an incredible performance of the Harvard Choruses for virtual graduation that involved a complicated process of additive recording over Zoom. -

Pianist WILLIAM WESTNEY Was the Top Piano Prize-Winner of The

LUNCHTIME CONCERT in CAFETERIA 4, UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN DENMARK at ODENSE 12:00 noon – 1:00 p.m. NOVEMBER 24, 2011 WILLIAM WESTNEY Piano From The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book II Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 – 1750) Prelude and Fugue in E major Prelude and Fugue in A minor Four Preludes Alexander Scriabin Op. 22 #3 (1872 – 1915) Op. 13 #4 Prelude for the Left Hand, op. 9 #1 Op. 11 #14 Evocation (from Iberia) Isaac Albeniz (1860 – 1909) Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Händel, op. 24 Johannes Brahms (1833 – 1897) Pianist WILLIAM WESTNEY returns to the University of Southern Denmark (Odense) to perform this lunchtime concert after having previously been in residence here as a Hans Christian Andersen Guest Professorial Fellow during the 2009-10 academic year. He was hosted by the Institute of Philosophy, Education and the Study of Religions, and he continues to be an active member of the SDU cross-disciplinary research group The Aesthetics of Music and Sound. Westney was the top piano prize-winner of the Geneva International Competition, and he appeared thereafter as soloist with such major orchestras as l'Orchestre de la Suisse Romande and the Houston, San Antonio and New Haven Symphonies. He holds a Bachelor of Arts degree from Queens College in New York and a Masters and Doctorate in performance from Yale University, all with highest honors. During his study in Italy under a Fulbright grant he was the only American winner in auditions held by Radiotelevisione Italiana. Solo recital appearances include New York's Lincoln Center, the National Gallery and Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., St. -

Battles Around New Music in New York in the Seventies

Presenting the New: Battles around New Music in New York in the Seventies A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY David Grayson, Adviser December 2012 © Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher 2012 i Acknowledgements One of the best things about reaching the end of this process is the opportunity to publicly thank the people who have helped to make it happen. More than any other individual, thanks must go to my wife, who has had to put up with more of my rambling than anybody, and has graciously given me half of every weekend for the last several years to keep working. Thank you, too, to my adviser, David Grayson, whose steady support in a shifting institutional environment has been invaluable. To the rest of my committee: Sumanth Gopinath, Kelley Harness, and Richard Leppert, for their advice and willingness to jump back in on this project after every life-inflicted gap. Thanks also to my mother and to my kids, for different reasons. Thanks to the staff at the New York Public Library (the one on 5th Ave. with the lions) for helping me track down the SoHo Weekly News microfilm when it had apparently vanished, and to the professional staff at the New York Public Library for Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, and to the Fales Special Collections staff at Bobst Library at New York University. Special thanks to the much smaller archival operation at the Kitchen, where I was assisted at various times by John Migliore and Samara Davis. -

Percussion Instruments of the Mind by Scott Deal

Percussion Instruments of the Mind By Scott Deal onsider what it was like to be a musician 100 or so years ago, when so was impractical. As a result, techniques to capture sounds on reel-to-reel tape many ideas grew into things that changed humanity: the lightbulb, ra- became a prime factor in the compositional process. Some well-known works in dio, car, airplane (what an amazing thing that must have been to see in the pioneering days of electro-acoustic percussion music include “Synchronisms those first years). Also, the new noise of the era: cities, traffic, machin- No. 5” (1969) for percussion quintet by Mario Davidovsky, and “Machine Music” Cery, electricity. It makes sense that un-pitched sound became the new territory (1964) for piano, percussion, and tape by Lejaren Hiller, in which the tape part for artists. There was a spirit of adventure in the air, and people began looking for was created with the aid of computational processes. new and different ways to express themselves. Currently, most musicians working with electronics have taken the genre In 1916, Edgar Varèse famously dreamt “of instruments obedient to my higher by using Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs) and smaller, more special- thought” (Hansen). An interesting exercise is to think about him imagining ized applications referred to as patches. Patches are often created specifically for various sounds, and then listen to his chamber work “Déserts” (1950–54) for just one piece of music, or to initiate a specific set of actions. They are designed winds, percussionists, piano, and electronic tape, or his landmark electronic tape and created in programming environments such as Max MSP, Pure Data (PD), “Poème électronique” (1958). -

Worldnewmusic Magazine

WORLDNEWMUSIC MAGAZINE ISCM During a Year of Pandemic Contents Editor’s Note………………………………………………………………………………5 An ISCM Timeline for 2020 (with a note from ISCM President Glenda Keam)……………………………..……….…6 Anna Veismane: Music life in Latvia 2020 March – December………………………………………….…10 Álvaro Gallegos: Pandemic-Pandemonium – New music in Chile during a perfect storm……………….....14 Anni Heino: Tucked away, locked away – Australia under Covid-19……………..……………….….18 Frank J. Oteri: Music During Quarantine in the United States….………………….………………….…22 Javier Hagen: The corona crisis from the perspective of a freelance musician in Switzerland………....29 In Memoriam (2019-2020)……………………………………….……………………....34 Paco Yáñez: Rethinking Composing in the Time of Coronavirus……………………………………..42 Hong Kong Contemporary Music Festival 2020: Asian Delights………………………..45 Glenda Keam: John Davis Leaves the Australian Music Centre after 32 years………………………….52 Irina Hasnaş: Introducing the ISCM Virtual Collaborative Series …………..………………………….54 World New Music Magazine, edition 2020 Vol. No. 30 “ISCM During a Year of Pandemic” Publisher: International Society for Contemporary Music Internationale Gesellschaft für Neue Musik / Société internationale pour la musique contemporaine / 国际现代音乐协会 / Sociedad Internacional de Música Contemporánea / الجمعية الدولية للموسيقى المعاصرة / Международное общество современной музыки Mailing address: Stiftgasse 29 1070 Wien Austria Email: [email protected] www.iscm.org ISCM Executive Committee: Glenda Keam, President Frank J Oteri, Vice-President Ol’ga Smetanová, -

Annotated Graduate Course Guide 2021-22

DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC AND DANCE GRADUATE COURSES 2021–2022 Note that some of the courses listed below may not be on SPIRE and/or you may find them on SPIRE w/ different room assignments. This Annotated Guide represents the department’s latest understanding of courses, days, times and credits. Because the Registrar’s Office is so busy, it may take time for new information to appear on SPIRE. COMPOSITION & ARRANGING Fall 2021 Music 586 – MIDI Studio Tech (3 credits) Required for M.M. in Composition Mon, 5:30 – 8:30, FAC 444 This course provides a comprehensive introduction to computer music, with a focus on studio techniques for computer music composition, performance, and recording, as well as an overview of the history of electronic music. The required text is Curtis Roads' The Computer Music Tutorial (1999). We will use the object oriented software Max/MSP to build virtual electronic musical instruments and prototypes from the textbook. Apple's Logic Pro music production software will also be used extensively throughout the course. Topics covered include ring modulation, amplitude modulation, FM synthesis, additive synthesis, sampling, filtering, compression, effects processing, step sequencing, multitrack recording and mixing, Fourier transform, syncing sound to digital video, techniques for live electronic music performance. We will study the compositions and techniques of electronic music pioneers such as Vladimir Ussachevsky, Otto Luening, Edgard Varese, Mario Davidovsky, Bruno Maderna, Milton Babbitt, Charles Dodge, John Chowning, Pierre Boulez, Gareth Loy, and others. Listening assignments include over 25 compositions from early electronic music to the present day. The course is designed to provide a thorough understanding of computer music, with relevance to graduate-level music students of all concentrations. -

Musical Analysis of Works for Performers and Electronics: an Alternative Approach

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1997 Musical analysis of works for performers and electronics: an alternative approach David Robert Boyle University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Boyle, David Robert, Musical analysis of works for performers and electronics: an alternative approach, Master of Arts (Hons.) thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1997. -

Geoffrey Kidde Music Department, Manhattanville College Telephone: (914) 798 - 2708 Email: [email protected]

Geoffrey Kidde Music Department, Manhattanville College Telephone: (914) 798 - 2708 Email: [email protected] Education: 1989 - 1995 Doctor of Musical Arts in Composition. Columbia University, New York, NY. Composition - Chou Wen-Chung, Mario Davidovsky, George Edwards. Theory - J. L. Monod, Jeff Nichols, Joseph Dubiel, David Epstein. Electronic and Computer Music - Mario Davidovsky, Brad Garton. Teaching Fellowships in Musicianship and Electronic Music. 1986 - 1988 Master of Music in Composition. New England Conservatory, Boston, MA. Composition - John Heiss, Malcolm Peyton. Theory - Robert Cogan, Pozzi Escot, James Hoffman. Electronic and Computer Music - Barry Vercoe, Robert Ceely. 1983 - 1985 Bachelor of Arts in Music. Columbia University, New York, NY. Theory - Severine Neff, Peter Schubert. Music History - Walter Frisch, Joel Newman, Elaine Sisman. 1981 - 1983 Princeton University, Princeton, NJ. Theory - Paul Lansky, Peter Westergaard. Computer Music - Paul Lansky. Improvisation - J. K. Randall. Teaching Experience: 2014 – present Professor of Music. Manhattanville College 2008 - 2014 Associate Professor of Music. Manhattanville College. 2002 - 2008 Assistant Professor of Music. Manhattanville College. Founding Director of Electronic Music Band (2004-2009). 1999 - 2002 Adjunct Assistant Professor of Music. Hofstra University, Hempstead, NY. 1998 - 2002 Adjunct Assistant Professor of Music. Queensborough Community College, CUNY. Bayside, NY. 1998 (fall semester) Adjunct Professor of Music. St. John’s University, Jamaica, NY. -

BEAUTIFUL NOISE Directions in Electronic Music

BEAUTIFUL NOISE Directions in Electronic Music www.ele-mental.org/beautifulnoise/ A WORK IN PROGRESS (3rd rev., Oct 2003) Comments to [email protected] 1 A Few Antecedents The Age of Inventions The 1800s produce a whole series of inventions that set the stage for the creation of electronic music, including the telegraph (1839), the telephone (1876), the phonograph (1877), and many others. Many of the early electronic instruments come about by accident: Elisha Gray’s ‘musical telegraph’ (1876) is an extension of his research into telephone technology; William Du Bois Duddell’s ‘singing arc’ (1899) is an accidental discovery made from the sounds of electric street lights. “The musical telegraph” Elisha Gray’s interesting instrument, 1876 The Telharmonium Thaddeus Cahill's telharmonium (aka the dynamophone) is the most important of the early electronic instruments. Its first public performance is given in Massachusetts in 1906. It is later moved to NYC in the hopes of providing soothing electronic music to area homes, restaurants, and theatres. However, the enormous size, cost, and weight of the instrument (it weighed 200 tons and occupied an entire warehouse), not to mention its interference of local phone service, ensure the telharmonium’s swift demise. Telharmonic Hall No recordings of the instrument survive, but some of Cahill’s 200-ton experiment in canned music, ca. 1910 its principles are later incorporated into the Hammond organ. More importantly, Cahill’s idea of ‘canned music,’ later taken up by Muzak in the 1960s and more recent cable-style systems, is now an inescapable feature of the contemporary landscape. -

Kyong Mee Choi • Dma

KYONG MEE CHOI • DMA Professor of Music Composition | Head of Music Composition Chicago College of Performing Arts | Roosevelt University 430 S. Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL 60605, AUD 950 Email: [email protected]/Phone: 312-322-7137 (O)/ 773-910-7157 (C)/ 773-728-7918 (H) Website: http://www.kyongmeechoi.com Home Address: 6123 N. Paulina St. Chicago, IL 60660, U.S.A. 1. EDUCATION • University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, U.S.A. Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Composition/Theory, 2005 Dissertation Composition: Gestural Trajectory for Two Pianos and Percussion Dissertation Title: Spatial Relationships in Electro-Acoustic Music and Painting • Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, U.S.A. Master of Arts in Music Composition, 1999 • Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea Completed Course Work in Master Study in Korean Literature majoring in Poetry, 1997 • Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea Bachelor of Science in Science Education majoring in Chemistry, 1995 PRINCIPAL STUDY • Composition: William Brooks, Agostino Di Scipio, Guy Garnett, Erik Lund, Robert Thompson, Scott Wyatt • Lessons and Master Classes: Coriun Aharonian, Larry Austin, George Crumb, James Dashow, Mario Davidovsky, Nickitas Demos, Orlando Jacinto Garcia, Vinko Globokar, Tristan Murail, Russell Pinkston, David Rosenboom, Joseph Butch Rovan, Frederic Rzewski, Kaija Saariaho, Stuart Smith, Morton Subotnick, Chen Yi • Music Software Programming and Electro-Acoustic Music: Guy Garnett (Max/MSP), Rick Taube (Common music/CLM/Lisp), Robert Thompson (CSound/Max), -

Grand Pianola Music R

Thursday, August 2, 2018, at 7:30 pm m a Grand Pianola Music r g International Contemporary o Ensemble r Christian Reif, Conductor M|M P M|M Courtney Bryan, Piano e Cory Smythe, Piano h Jacob Greenberg, Piano Peter Evans, Trumpet T Joshua Rubin, Clarinet Ryan Muncy, Saxophone Quince Ensemble M|M Amanda DeBoer Bartlett, Soprano Liz Pearse, Soprano Kayleigh Butcher, Mezzo-Soprano COURTNEY BRYAN Songs of Laughing, Smiling, and Crying (2012) BRYAN GEORGE LEWIS Voyager (1987/2018) EVANS, RUBIN, MUNCY, SMYTHE, YAMAHA DISKLAVIER PIANO PERFORMED BY “VOYAGER” (Lewis interactive music system) Intermission M|M Mostly Mozart Festival debut (Program continued) Please make certain all your electronic devices are switched off. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Gerald W. Lynch Theater at John Jay College Mostly Mozart Festival American Express is the lead sponsor of the Mostly Mozart Festival Endowment support is provided by Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance The Mostly Mozart Festival is also made possible by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, The Ford Foundation, and Rita E. and Gustave M. Hauser. Additional support is provided by The Shubert Foundation, LuEsther T. Mertz Charitable Trust, The Howard Gilman Foundation, The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc., The Katzenberger Foundation, Inc., Mitsui & Co. (U.S.A.), Inc, Mitsubishi Corporation (Americas), Sumitomo Corporation of Americas, J.C.C. Fund, Japanese Chamber of Commerce and Industry of New York, Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal U.S.A., Inc, Great Performers Circle, Chairman’s Council, Friends of Mostly Mozart , and Friends of Lincoln Center Nespresso is the Official Coffee of Lincoln Center NewYork-Presbyterian is the Official Hospital of Lincoln Center “Summer at Lincoln Center” is supported by Bubly Artist Catering provided by Zabar’s and Zabars.com UPCOMING MOSTLY MOZART FESTIVAL EVENTS: Friday, August 3 at 10:00 pm in the Stanley H. -

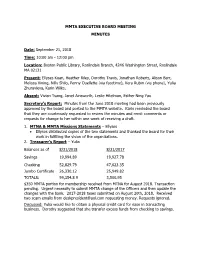

MMTA EXECUTIVE BOARD MEETING MINUTES Date: September

MMTA EXECUTIVE BOARD MEETING MINUTES Date: September 21, 2018 Time: 10:00 am - 12:00 pm Location: Boston Public Library, Roslindale Branch, 4246 Washington Street, Roslindale MA 02131 Present: Ellyses Kuan, Heather Riley, Dorothy Travis, Jonathan Roberts, Alison Barr, Melissa Vining, Nilly Shilo, Penny Ouellette (via facetime), Vera Rubin (via phone), Yulia Zhuravleva, Karin Wilks, Absent: Vivian Tsang, Janet Ainsworth, Leslie Hitelman, Esther Ning Yao Secretary’s Report: Minutes from the June 2018 meeting had been previously approved by the board and posted to the MMTA website. Karin reminded the board that they are courteously requested to review the minutes and remit comments or requests for change to her within one week of receiving a draft. 1. MTNA & MMTA Missions Statements – Ellyses Ellyses distributed copies of the two statements and thanked the board for their work in fulfilling the vision of the organizations. 2. Treasurer’s Report – Yulia Balances as of 8/31/2018 8/31/2017 Savings 19,994.89 19,927.78 Checking 52,829.79 47,623.35 Jumbo Certificate 26,330.12 25,949.82 TOTALS: 99,154.8 9 3,500.95 $350 MMTA portion for membership received from MTNA for August 2018. Transaction pending. Urgent necessity to submit MMTA change of the Officers and then update the changes with the bank. 2017-2018 taxes submitted on August 20th, 2018. Received two scam emails from [email protected] requesting money. Requests ignored. Discussed: Yulia would like to obtain a physical credit card for ease in transacting business. Dorothy suggested that she transfer excess funds from checking to savings.