Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morning Coffe E

PAGE 10 Yankton Daily Press & Dakotan ■ Saturday, March 5, 2011 www.yankton.net PHOTOS OF THE DAY SCOREBOARD Sioux Falls Washington 55, Christa Paul, Madison; Shannon Harrisburg; Taylor Harris, Harrisburg; Sacramento 15 44 .254 26 1/2 Dallas at San Jose, 9:30 p.m. City Basketball Yankton 37 Spurgin, Madison; Lexy Hofer, West Josh Mettler, West Central; Tyler Thursday’s Games Sunday’s Games A Soleful Crowd MEN’S C LEAGUE District 3AA Third Place Central; Allie Macdonald, West Central; Stolsmark, West Central; Tim Weber, Orlando 99, Miami 96 Philadelphia at N.Y. Rangers, RESULTS: Gause Honey def. Huron 66, Aberdeen Central 50 Brianna McEntee, Lennox; Lexi West Central; Spencer Hastings, West Denver 103, Utah 101 11:30 a.m. Miller Painting 59-51; Cortrust def. The District 4AA Regenrus, Vermillion Central; Brett Bye, Vermillion, Regan Friday’s Games New Jersey at N.Y. Islanders, 2 Blazers 94-38 Championship HONORABLE MENTION: Katie Bye, Vermillion, Lance Burkhart, New Jersey 116, Toronto 103 p.m. STANDINGS: Cortrust 8-2, Miller Rapid City Central 59, Sturgis 49 Goldammer, Harrisburg; Bailey Milne, Vermillion; Dexter Mehlhaf, Vermillion; Chicago 89, Orlando 81 Washington at Florida, 4 p.m. Painting 6-3, Waterboys 5-4, Gause Third Place Madison; Hilary Mettler, West Central; Will Mart, Vermillion, Austin Lynde, Philadelphia 111, Minnesota 100 Buffalo at Minnesota, 5 p.m. Honey 4-6, The Blazers 1-9 Rapid City Stevens 65, Spearfish Chelsea Sweeter, Lennox; Kelly Lennox Oklahoma City 111, Atlanta 104 Nashville at Calgary, 7 p.m. 38 Amundson, Vermillion HONORABLE MENTION: Derek Boston 107, Golden State 103 Vancouver at Anaheim, 7 p.m. -

Media Kit Bakersfield Condors Vs Ontario Reign Game #369: Friday

Media Kit Bakersfield Condors vs Ontario Reign Game #369: Friday, December 16, 2016 theahl.com Bakersfield Condors (10-8-2-0) vs. Ontario Reign (11-6-5-0) Dec 16, 2016 -- Citizens Business Bank Arena AHL Game #369 GOALIES GOALIES # Name Ht Wt GP W L OT SO GAA SV% # Name Ht Wt GP W L OT SO GAA SV% 31 Laurent Brossoit 6-3 202 13 6 6 1 2 2.23 0.927 1 Jack Campbell 6-3 195 13 8 3 2 1 2.91 0.895 34 Nick Ellis 6-1 180 8 4 2 1 0 2.39 0.931 36 Jack Flinn 6-8 233 5 1 2 1 0 3.41 0.874 SKATERS SKATERS # Name Pos Ht Wt GP G A Pts. PIM +/- # Name Pos Ht Wt GP G A Pts. PIM +/- 2 Mark Fraser D 6-3 220 20 0 1 1 38 0 2 Damir Sharipzianov D 6-2 205 9 0 0 0 23 -1 3 Dillon Simpson D 6-2 197 12 1 0 1 8 3 5 Vincent LoVerde D 5-11 205 22 5 11 16 13 0 5 Ben Betker D 6-6 225 15 1 2 3 10 2 6 Paul LaDue D 6-1 186 19 1 9 10 12 3 6 David Musil D 6-4 207 16 1 5 6 8 4 7 Brett Sutter C 6-0 192 21 4 5 9 15 4 7 Jujhar Khaira C 6-3 215 14 5 5 10 10 2 8 Zach Leslie D 6-0 175 20 3 6 9 13 -1 8 Griffin Reinhart D 6-4 212 10 0 2 2 15 7 9 Adrian Kempe LW 6-1 187 21 4 3 7 22 -5 11 Joey Benik LW 5-10 175 16 4 1 5 0 -6 10 Alex Lintuniemi D 6-2 214 12 0 2 2 2 -4 12 Ryan Hamilton LW 6-2 225 20 7 10 17 19 8 11 Patrick Bjorkstrand C 6-1 176 6 3 1 4 2 1 14 Kyle Platzer C 6-0 185 19 0 4 4 2 -4 14 Rob Scuderi D 6-0 218 6 0 1 1 4 -1 15 Jordan Oesterle D 6-0 182 8 3 2 5 0 2 15 Paul Bissonnette LW 6-2 216 16 0 3 3 31 3 17 Joey LaLeggia D 5-10 185 20 2 5 7 14 0 16 Sean Backman RW 5-8 165 22 4 9 13 6 -7 18 Josh Currie C 5-11 190 19 4 3 7 4 2 17 T.J. -

Dobber's 2010-11 Fantasy Guide

DOBBER’S 2010-11 FANTASY GUIDE DOBBERHOCKEY.COM – HOME OF THE TOP 300 FANTASY PLAYERS I think we’re at the point in the fantasy hockey universe where DobberHockey.com is either known in a fantasy league, or the GM’s are sleeping. Besides my column in The Hockey News’ Ultimate Pool Guide, and my contributions to this year’s Score Forecaster (fifth year doing each), I put an ad in McKeen’s. That covers the big three hockey pool magazines and you should have at least one of them as part of your draft prep. The other thing you need, of course, is this Guide right here. It is not only updated throughout the summer, but I also make sure that the features/tidbits found in here are unique. I know what’s in the print mags and I have always tried to set this Guide apart from them. Once again, this is an automatic download – just pick it up in your downloads section. Look for one or two updates in August, then one or two updates between September 1st and 14th. After that, when training camp is in full swing, I will be updating every two or three days right into October. Make sure you download the latest prior to heading into your draft (and don’t ask me on one day if I’ll be updating the next day – I get so many of those that I am unable to answer them all, just download as late as you can). Any updates beyond this original release will be in bold blue. -

Salary Caps in Professional Sports: Closing the Kovalchuk Loophole in National Hockey League Player Contracts♦

SALARY CAPS IN PROFESSIONAL SPORTS: CLOSING THE KOVALCHUK LOOPHOLE IN NATIONAL HOCKEY LEAGUE PLAYER CONTRACTS♦ INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 375 I. BACKGROUND ........................................................................ 377 A. Salary Caps and the 2005 Collective Bargaining Agreement ................................................... 377 II. THE LOOPHOLE ...................................................................... 382 A. Clubs Begin to Exploit .............................................. 382 B. The Final Straw.......................................................... 383 III. THE ARBITRATION HEARINGS ................................................ 384 A. The Kovalchuk Decision ........................................... 384 B. Not A New Problem .................................................. 388 C. An End to the Matter?................................................ 391 IV. FIXING THE CBA .................................................................... 393 A. Remaining Loopholes ................................................ 393 B. Flawed Solutions ....................................................... 393 1. League-Issued Advisory Opinions ........................ 393 2. Amend Section 26.3 .............................................. 394 3. National Basketball Association Approach .......... 395 C. Salary Cap Solution ................................................... 398 CONCLUSION .................................................................................... -

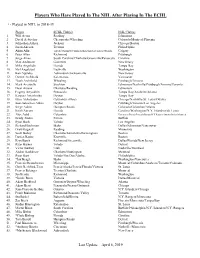

Players Who Have Played in the NHL After Playing in the ECHL

Players Who Have Played In The NHL After Playing In The ECHL * - Played in NHL in 2020-21 Player ECHL Club(s) NHL Club(s) 1. Will Acton Reading Edmonton 2. David Aebischer Chesapeake/Wheeling Colorado/Montreal/Phoenix 3. Johnathan Aitken Jackson Chicago/Boston 4. *Jack Ahcan Jacksonville Boston 5. Jason Akeson Trenton Philadelphia 6. Akim Aliu Toledo/Gwinnett/Colorado/Bakersfield/Florida/Orlando Calgary 7. *Frederic Allard Norfolk Nashville 8. Peter Allen Richmond Pittsburgh 9. Jorge Alves South Carolina/Charlotte/Greenville/Pensacola Carolina 10. Matt Anderson Gwinnett New Jersey 11. Mike Angelidis Florida Tampa Bay 12. Mel Angelstad Nashville Washington 13. Ken Appleby Adirondack/Jacksonville/Florida New Jersey 14. Darren Archibald Kalamazoo Vancouver 15. *Josh Archibald Wheeling Pittsburgh/Arizona/Edmonton 16. Mark Arcobello Stockton Edmonton/Nashville/Pittsburgh/Arizona/Toronto 17. Dean Arsene Charlotte/Reading Edmonton 18. Evgeny Artyukhin Pensacola Tampa Bay/Anaheim/Atlanta 19. Kaspars Astashenko Dayton Tampa Bay 20. Blair Atcheynum Columbus (Ohio) Chicago/Nashville/St. Louis/Ottawa 21. Jean-Sebastien Aubin Dayton Pittsburgh/Toronto/Los Angeles 22. Serge Aubin Hampton Roads Colorado/Columbus/Atlanta 23. Keith Aucoin Florida Carolina/Washington/N.Y. Islanders/St. Louis 24. Alex Auld Columbia Vancouver/Florida/Phoenix/Boston/N.Y.Rangers/Ottawa/Dallas/Montreal 25. Brady Austin Elmira Buffalo 26. Ryan Bach Toledo Los Angeles 27. Richard Bachman Idaho Dallas/Edmonton/Vancouver 28. Drew Bagnall Reading Minnesota 29. Scott Bailey Charlotte/Johnstown/Birmingham Boston 30. Darren Banks Knoxville Boston 31. Krys Barch Richmond/Greenville Dallas/Florida/New Jersey 32. Ryan Barnes Toledo Detroit 33. Victor Bartley Utah Nashville/Montreal 34. Andrei Bashkirov Charlotte/Huntington Montreal 35. -

Leaguestat Daily Report for the ECHL Generated 2009-06-23 11:13 Am

Leaguestat Daily Report for the ECHL Generated 2009-06-23 11:13 am Standings AMERICAN NORTH GP W L OTL SOL PTS PCT GF GA PIM HOME ROAD LAST TEN STREAK xy Dayton 72 37 26 2 7 83 0.576 213 191 1410 18-13-1-4 19-13-1-3 3-4-1-2 0-1-0-1 x Toledo 72 39 30 1 2 81 0.562 211 220 1634 27-9-0-0 12-21-1-2 6-3-1-0 4-0-0-0 x Cincinnati 72 37 29 4 2 80 0.556 213 198 1667 19-13-2-2 18-16-2-0 3-6-1-0 0-2-0-0 x Trenton 72 36 31 1 4 77 0.535 250 242 1400 18-15-1-2 18-16-0-2 5-5-0-0 0-1-0-0 x Johnstown 72 33 33 3 3 72 0.500 216 232 1204 18-16-2-0 15-17-1-3 6-4-0-0 1-0-0-0 Reading 72 32 33 2 5 71 0.493 221 235 1700 17-15-1-3 15-18-1-2 4-5-1-0 0-1-0-0 Wheeling 72 32 34 2 4 70 0.486 215 255 1521 18-14-2-2 14-20-0-2 7-3-0-0 1-0-0-0 SOUTH GP W L OTL SOL PTS PCT GF GA PIM HOME ROAD LAST TEN STREAK xy Florida 72 44 22 4 2 94 0.653 272 212 1346 23-11-1-1 21-11-3-1 6-3-0-1 4-0-0-0 x Texas 72 41 22 5 4 91 0.632 265 222 1521 21-8-4-3 20-14-1-1 6-4-0-0 0-2-0-0 x Gwinnett 72 41 24 5 2 89 0.618 289 256 1324 26-8-1-1 15-16-4-1 5-5-0-0 0-1-0-0 x Charlotte 72 42 27 1 2 87 0.604 252 220 1561 22-14-0-0 20-13-1-2 7-3-0-0 0-1-0-0 x Augusta 72 39 29 1 3 82 0.569 258 265 1230 21-13-1-1 18-16-0-2 6-3-0-1 0-2-0-1 x South Carolina 72 36 27 4 5 81 0.562 250 251 1400 18-12-3-3 18-15-1-2 4-4-1-1 1-0-0-0 x Columbia 72 29 34 4 5 67 0.465 217 256 1348 14-17-1-4 15-17-3-1 5-5-0-0 2-0-0-0 Pensacola 72 20 46 2 4 46 0.319 233 318 1777 12-19-2-3 8-27-0-1 1-7-1-1 1-0-0-0 NATIONAL PACIFIC GP W L OTL SOL PTS PCT GF GA PIM HOME ROAD LAST TEN STREAK xy Las Vegas 72 46 12 6 8 106 0.736 231 187 1379 -

Template-Free Data-To-Text Generation of Finnish Sports News

Template-free Data-to-Text Generation of Finnish Sports News Jenna Kanerva, Samuel Ronnqvist¨ , Riina Kekki, Tapio Salakoski and Filip Ginter TurkuNLP Department of Future Technologies University of Turku, Finland fjmnybl,saanro,rieeke,sala,[email protected] Abstract Further, this development needs to be repeated for every domain, as the templates are not easily trans- News articles such as sports game reports ferred across domains. Examples of the template- are often thought to closely follow the un- based news generation systems for Finnish are derlying game statistics, but in practice Voitto2 by the Finnish Public Service Broadcast- they contain a notable amount of back- ing Company (YLE) used for sports news genera- ground knowledge, interpretation, insight tion, as well as Vaalibotti (Leppanen¨ et al., 2017), into the game, and quotes that are not a hybrid machine learning and template-based sys- present in the official statistics. This tem used for election news. poses a challenge for automated data-to- Wiseman et al. (2018) suggested a neural tem- text news generation with real-world news plate generation, which jointly models latent tem- corpora as training data. We report on plates and text generation. Such a system in- the development of a corpus of Finnish creases interpretability and controllability of the ice hockey news, edited to be suitable generation, however, recent sequence-to-sequence for training of end-to-end news generation systems represent the state-of-the-art in data-to- methods, as well as demonstrate genera- text generation. (Dusekˇ et al., 2018) tion of text, which was judged by journal- In this paper, we report on the development ists to be relatively close to a viable prod- of a news generation system for the Finnish uct. -

Hockey and Spectacle: Critical Reflections on Canadian Culture

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Hockey and Spectacle: Critical Reflections on Canadian Culture By Peter Zuurbier A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATIONS CALGARY, ALBERTA JULY, 2011 Peter Zuurbier 2011 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-81959-3 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-81959-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

![Arxiv:1910.01863V1 [Cs.CL] 4 Oct 2019 Volume of News, Combined with the Expectation of Our Aim Is to Generate Reports That Give an a Relatively Straightforward Task](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6546/arxiv-1910-01863v1-cs-cl-4-oct-2019-volume-of-news-combined-with-the-expectation-of-our-aim-is-to-generate-reports-that-give-an-a-relatively-straightforward-task-6936546.webp)

Arxiv:1910.01863V1 [Cs.CL] 4 Oct 2019 Volume of News, Combined with the Expectation of Our Aim Is to Generate Reports That Give an a Relatively Straightforward Task

Template-free Data-to-Text Generation of Finnish Sports News Jenna Kanerva, Samuel Ronnqvist¨ , Riina Kekki, Tapio Salakoski and Filip Ginter TurkuNLP Department of Future Technologies University of Turku, Finland fjmnybl,saanro,rieeke,sala,[email protected] Abstract Further, this development needs to be repeated for every domain, as the templates are not easily trans- News articles such as sports game reports ferred across domains. Examples of the template- are often thought to closely follow the un- based news generation systems for Finnish are derlying game statistics, but in practice Voitto2 by the Finnish Public Service Broadcast- they contain a notable amount of back- ing Company (YLE) used for sports news genera- ground knowledge, interpretation, insight tion, as well as Vaalibotti (Leppanen¨ et al., 2017), into the game, and quotes that are not a hybrid machine learning and template-based sys- present in the official statistics. This tem used for election news. poses a challenge for automated data-to- Wiseman et al. (2018) suggested a neural tem- text news generation with real-world news plate generation, which jointly models latent tem- corpora as training data. We report on plates and text generation. Such a system in- the development of a corpus of Finnish creases interpretability and controllability of the ice hockey news, edited to be suitable generation, however, recent sequence-to-sequence for training of end-to-end news generation systems represent the state-of-the-art in data-to- methods, as well as demonstrate genera- text generation. (Dusekˇ et al., 2018) tion of text, which was judged by journal- In this paper, we report on the development ists to be relatively close to a viable prod- of a news generation system for the Finnish uct. -

Players Who Have Played in the NHL After Playing in the ECHL

Players Who Have Played In The NHL After Playing In The ECHL * - Played in NHL in 2018-19 Player ECHL Club(s) NHL Club(s) 1. Will Acton Reading Edmonton 2. David Aebischer Chesapeake/Wheeling Colorado/Montreal/Phoenix 3. Johnathan Aitken Jackson Chicago/Boston 4. Jason Akeson Trenton Philadelphia 5. Akim Aliu Toledo/Gwinnett/Colorado/Bakersfield/Florida/Orlando Calgary 6. Peter Allen Richmond Pittsburgh 7. Jorge Alves South Carolina/Charlotte/Greenville/Pensacola Carolina 8. Matt Anderson Gwinnett New Jersey 9. Mike Angelidis Florida Tampa Bay 10. Mel Angelstad Nashville Washington 11. Ken Appleby Adirondack/Jacksonville New Jersey 12. Darren Archibald Kalamazoo Vancouver 13. *Josh Archibald Wheeling Pittsburgh/Arizona 14. Mark Arcobello Stockton Edmonton/Nashville/Pittsburgh/Arizona/Toronto 15. Dean Arsene Charlotte/Reading Edmonton 16. Evgeny Artyukhin Pensacola Tampa Bay/Anaheim/Atlanta 17. Kaspars Astashenko Dayton Tampa Bay 18. Blair Atcheynum Columbus (Ohio) Chicago/Nashville/St. Louis/Ottawa 19. Jean-Sebastien Aubin Dayton Pittsburgh/Toronto/Los Angeles 20. Serge Aubin Hampton Roads Colorado/Columbus/Atlanta 21. Keith Aucoin Florida Carolina/Washington/N.Y. Islanders/St. Louis 22. Alex Auld Columbia Vancouver/Florida/Phoenix/Boston/N.Y.Rangers/Ottawa/Dallas/Montreal 23. Brady Austin Elmira Buffalo 24. Ryan Bach Toledo Los Angeles 25. Richard Bachman Idaho Dallas/Edmonton/Vancouver 26. Drew Bagnall Reading Minnesota 27. Scott Bailey Charlotte/Johnstown/Birmingham Boston 28. Darren Banks Knoxville Boston 29. Krys Barch Richmond/Greenville Dallas/Florida/New Jersey 30. Ryan Barnes Toledo Detroit 31. Victor Bartley Utah Nashville/Montreal 32. Andrei Bashkirov Charlotte/Huntington Montreal 33. Ryan Bast Toledo/Pee Dee/Alaska Philadelphia 34. *Jay Beagle Idaho Washington/Vancouver 35. -

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 5/20/2020 Boston Bruins Nashville Predators 1174673 This Date in Bruins History: Tim Thomas shuts out 1174696 Nashville wants to host games if NHL resumes season in Lightning in East Final centralized locations 1174674 Bruins expected to get AHL reinforcements should NHL season resume New Jersey Devils 1174697 N.Y. Gov. Andrew Cuomo doubles down on sports without Buffalo Sabres fans in the stands: ‘Ready, willing and able’ 1174675 Sabres prospect Tage Thompson 'feeling good' while 1174698 NHL players’ fear of Carey Price part of messy return rehabbing from surgery equation BuffaloSabres New York Rangers 1174676 Buffalo Sabres sue immigration officials over denial to 1174699 Rangers' David Quinn to do weekly interview show on grant green card for trainer MSG 1174677 Boston’s bountiful title banners evoke aspiration — and envy — in Buffalo fans Ottawa Senators 1174700 Ottawa Senators' conditioning staff keeping players ready Calgary Flames for every scenario 1174678 Flames prospect Dustin Wolf wins WHL's Del Wilson 1174701 NHL players returning to the ice in Ottawa this week Trophy, takes aim at career shutout record 1174702 Mikkel Boedker signs two-year deal with Lugano in Swiss league starting next season Carolina Hurricanes 1174679 The Carolina Hurricanes are close to a deal to remain at Philadelphia Flyers PNC Arena through 2029 1174703 If NHL returns with gimmicky 24-team tourney, it shouldn’t 1174680 Raleigh native Alex Wilkinson found a different kind of use it beyond this season | Sam Carchidi hockey success -

Sports (2016) Sports / Edited by David Taras and Christopher Waddell

HOW CANADIANS COMMUNICATE V HOW CANADIANS COMMUNICATE V Edited by David Taras and Christopher Waddell Copyright © 2016 David Taras and Christopher Waddell Published by AU Press, Athabasca University 1200, 10011 – 109 Street, Edmonton, AB T5J 3S8 ISBN 978-1-77199-007-3 (pbk.) 978-1-77199-008-0 (PDF) 978-1-77199-009-7 (epub) doi: 10.15215/aupress/9781771990073.01 Cover design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design Interior design by Sergiy Kozakov Printed and bound in Canada by Marquis Book Printers Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Sports (2016) Sports / edited by David Taras and Christopher Waddell. (How Canadians communicate ; V) This volume emerged from a conference that was part of the How Canadians Communicate series of conferences held in Banff in October 2012. Includes bibliographical references and index. Issued in print and electronic formats. 1. Mass media and sports—Canada. 2. Sports—Social aspects—Canada. I. Taras, David, 1950-, author, editor II. Waddell, Christopher Robb, author, editor III. Title. IV. Series: How Canadians communicate (Series) ; 5 GV742.S66 2016 070.4'497960971 C2015-904359-X C2015-904360-3 We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CFB) for our publishing activities. Assistance provided by the Government of Alberta, Alberta Media Fund. This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons License, Attribution– Noncommercial–NoDerivative Works 4.0 International: see www.creativecommons.org. The text may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes, provided that credit is given to the original author. To obtain permission for uses beyond those outlined in the Creative Commons license, please contact AU Press, Athabasca University, at [email protected].