Aliya Hamid Rao January 25Th 2011 Penn DCC Workshop 1 with One

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Deobandi Ulema in Strengthening the Foundations of Indian Freedom Movement (1857-1924)

The Role of Deobandi Ulema in Strengthening the Foundations of Indian Freedom Movement (1857-1924) The Role of Deobandi Ulema in Strengthening the Foundations of Indian Freedom Movement (1857-1924) * Turab-ul-Hassan Sargana **Khalil Ahmed ***Shahid Hassan Rizvi Abstract The main objective of the present study is to explain the role of the Deobandi faction of scholars in Indian Freedom Movement. In fact, there had been different schools of thought who supported the Movement and their works and achievements cannot be forgotten. Historically, Ulema played a key role in the politics of subcontinent and the contribution of Dar ul Uloom Deoband, Mazahir-ul- Uloom (Saharanpur), Madrassa Qasim-ul-Uloom( Muradabad), famous madaris of Deobandi faction is a settled fact. Their role became both effective and emphatic with the passage of time when they sided with the All India Muslim League. Their role and services in this historic episode is the focus of the study in hand. Keywords: Deoband, Aligarh Movement, Khilafat, Muslim League, Congress Ulama in Politics: Retrospect: Besides performing their religious obligations, the religious ulema also took part in the War of Freedom 1857, similar to the other Indians, and it was only due to their active participation that the movement became in line and determined. These ulema used the pen and sword to fight against the British and it is also a fact that ordinary causes of 1857 War were blazed by these ulema. Mian Muhammad Shafi writes: Who says that the fire lit by Sayyid Ahmad was extinguished or it had cooled down? These were the people who encouraged Muslims and the Hindus to fight against the British in 1857. -

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction The Invention of an Ethnic Nationalism he Hindu nationalist movement started to monopolize the front pages of Indian newspapers in the 1990s when the political T party that represented it in the political arena, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP—which translates roughly as Indian People’s Party), rose to power. From 2 seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian parliament, the BJP increased its tally to 88 in 1989, 120 in 1991, 161 in 1996—at which time it became the largest party in that assembly—and to 178 in 1998. At that point it was in a position to form a coalition government, an achievement it repeated after the 1999 mid-term elections. For the first time in Indian history, Hindu nationalism had managed to take over power. The BJP and its allies remained in office for five full years, until 2004. The general public discovered Hindu nationalism in operation over these years. But it had of course already been active in Indian politics and society for decades; in fact, this ism is one of the oldest ideological streams in India. It took concrete shape in the 1920s and even harks back to more nascent shapes in the nineteenth century. As a movement, too, Hindu nationalism is heir to a long tradition. Its main incarnation today, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS—or the National Volunteer Corps), was founded in 1925, soon after the first Indian communist party, and before the first Indian socialist party. -

The Khilafat Movement in India 1919-1924

THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT IN INDIA 1919-1924 VERHANDELINGEN VAN HET KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR T AAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE 62 THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT IN INDIA 1919-1924 A. C. NIEMEIJER THE HAGUE - MAR TINUS NIJHOFF 1972 I.S.B.N.90.247.1334.X PREFACE The first incentive to write this book originated from a post-graduate course in Asian history which the University of Amsterdam organized in 1966. I am happy to acknowledge that the university where I received my training in the period from 1933 to 1940 also provided the stimulus for its final completion. I am greatly indebted to the personal interest taken in my studies by professor Dr. W. F. Wertheim and Dr. J. M. Pluvier. Without their encouragement, their critical observations and their advice the result would certainly have been of less value than it may be now. The same applies to Mrs. Dr. S. C. L. Vreede-de Stuers, who was prevented only by ill-health from playing a more active role in the last phase of preparation of this thesis. I am also grateful to professor Dr. G. F. Pijper who was kind enough to read the second chapter of my book and gave me valuable advice. Beside this personal and scholarly help I am indebted for assistance of a more technical character to the staff of the India Office Library and the India Office Records, and also to the staff of the Public Record Office, who were invariably kind and helpful in guiding a foreigner through the intricacies of their libraries and archives. -

7 Modernity and ... Ulum Deoband Movement.Pdf

Modernity and Islam in South-Asia Journal of Academic Research for Humanities Journal of Academic Research for Humanities (JARH) Vol. 2, No. 1 (2020) Modernity and Islam in South-Asia: Approach of Darul Ulum Deoband Movement Published online: 30-12-2020 1st Author 2nd Author 3rd Author Dr. Muhammad Naveed Dr. Abul Rasheed Qadari Dr. Muhammad Rizwan Akhtar Associate Professor Associate Professor, Assistant Professor Department of Arabic and Department of Pakistan Department of Pakistan Studies, Islamic Studies, Studies, Abbottabad University of Science University of Lahore, Lahore Abbottabad University of and Technology, (Pakistan) Science and Technology, Abbottabad (Pakistan) Email: [email protected] Abbottabad (Pakistan) [email protected] drmuhammadrizwan_hu@yah oo.com CORRESPONDING AUTHOR 1st Author Dr. Muhammad Naveed Akhtar Assistant Professor Department of Pakistan Studies, Abbottabad University of Science and Technology, Abbottabad (Pakistan) [email protected] Abstract: The response of South Asian Muslims to the British occupation of India and the socio-cultural and institutional reforms that they induced were manifold. The attempts by the British to inculcate modernism in Indian societies was taken up by the Muslims as a political and cultural challenge. Unlike the Muslim ideologues such as Sir Syed Ahmad Khan (1817-18), who launched Aligarh Movement adopting progressive and loyalist approach, the exponent Deoband Movement showed militant resistance towards British imperialism and by sticking to their religious dogmas attempted to reform the society along with orthodox lines. Yet, they afterwards modernized their educational institutions which appeared to be one of the dominant set of Islam and made seminary second largest religious educational institution in the Muslim World. -

The Great Calcutta Killings Noakhali Genocide

1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE 1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE A HISTORICAL STUDY DINESH CHANDRA SINHA : ASHOK DASGUPTA No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. Published by Sri Himansu Maity 3B, Dinabandhu Lane Kolkata-700006 Edition First, 2011 Price ` 500.00 (Rupees Five Hundred Only) US $25 (US Dollars Twenty Five Only) © Reserved Printed at Mahamaya Press & Binding, Kolkata Available at Tuhina Prakashani 12/C, Bankim Chatterjee Street Kolkata-700073 Dedication In memory of those insatiate souls who had fallen victims to the swords and bullets of the protagonist of partition and Pakistan; and also those who had to undergo unparalleled brutality and humility and then forcibly uprooted from ancestral hearth and home. PREFACE What prompted us in writing this Book. As the saying goes, truth is the first casualty of war; so is true history, the first casualty of India’s struggle for independence. We, the Hindus of Bengal happen to be one of the worst victims of Islamic intolerance in the world. Bengal, which had been under Islamic attack for centuries, beginning with the invasion of the Turkish marauder Bakhtiyar Khilji eight hundred years back. We had a respite from Islamic rule for about two hundred years after the English East India Company defeated the Muslim ruler of Bengal. Siraj-ud-daulah in 1757. But gradually, Bengal had been turned into a Muslim majority province. -

Index More Information

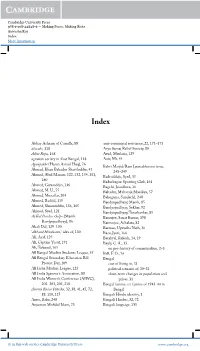

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42828-6 — Making Peace, Making Riots Anwesha Roy Index More Information Index 271 Index Abhay Ashram of Comilla, 88 anti-communal resistance, 22, 171–175 abwabs, 118 Arya Samaj Relief Society, 80 Adim Ripu, 168 Azad, Maulana, 129 agrarian society in East Bengal, 118 Aziz, Mr, 44 Agunpakhi (Hasan Azizul Huq), 76 Babri Masjid/Ram Janmabhoomi issue, Ahmad, Khan Bahadur Sharifuddin, 41 248–249 Ahmed, Abul Mansur, 122, 132, 134, 151, Badrudduja, Syed, 35 160 Badurbagan Sporting Club, 161 Ahmed, Giyasuddin, 136 Bagchi, Jasodhara, 16 Ahmed, M. U., 75 Bahadur, Maharaja Manikya, 57 Ahmed, Muzaffar, 204 Bahuguna, Sunderlal, 240 Ahmed, Rashid, 119 Bandyopadhyay, Manik, 85 Ahmed, Shamsuddin, 136, 165 Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar, 92 Ahmed, Syed, 121 Bandyopadhyay, Tarashankar, 85 Aj Kal Porshur Golpo (Manik Banerjee, Sanat Kumar, 198 Bandyopadhyay), 86 Bannerjee, Ashalata, 82 Akali Dal, 129–130 Barman, Upendra Nath, 36 ‘Akhand Hindustan,’ idea of, 130 Basu, Jyoti, 166 Ali, Asaf, 129 Batabyal, Rakesh, 14, 19 Ali, Captain Yusuf, 191 Bayly, C. A., 13 Ali, Tafazzal, 165 on pre-history of communalism, 2–3 All Bengal Muslim Students League, 55 Bell, F. O., 76 All Bengal Secondary Education Bill Bengal Protest Day, 109 cost of living in, 31 All India Muslim League, 123 political scenario of, 30–31 All India Spinner’s Association, 88 short-term changes in population and All India Women’s Conference (AIWC), prices, 31 202–203, 205, 218 Bengal famine. see famine of 1943-44 in Amrita Bazar Patrika, 32, 38, 41, 45, 72, Bengal 88, 110, 115 Bengali Hindu identity, 1 Amte, Baba, 240 Bengali Hindus, 32, 72 Anjuman Mofidul Islam, 73 Bengali language, 135 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42828-6 — Making Peace, Making Riots Anwesha Roy Index More Information 272 Index The Bengali Merchants Association, 56 C. -

Khalifat and Non-Cooperation Movement in India

Khalifat and Non-Cooperation Movement in India Two mass movements were organized in 1919-1922 to oppose the British rule in India— i)the Khilafat ii) Non-Cooperation. Though the issues were separate but they adopted a unified plan of action—that of non-violent, non- cooperation. The immediate thrust to the movement was provided by the Khilafat issue, though not directly n linked but gave an added advantage of cementing Hindu-Muslim unity against the British. Background: Series of events after the First World War serve as the background which belied all hopes of the Government’s generosity towards the Indian subjects. Few of them are 1. The Rowlatt Act, the imposition of martial law in Punjab and the Jallianwalla Bagh massacre exposed the brutal and uncivilised face of the foreign rule. 2. The Hunter Commission on the Punjab atrocities proved to be eyewash. In fact, the House of Lords (of the British Parliament) endorsed General Dyer’s action and the British public showed solidarity with General Dyer by helping The Morning Post collect 30,000 pounds for him. 3. The Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms with their ill- conceived scheme of Dyarchy failed to satisfy the rising demand of the Indians for self-government. 4. The economic situation of the country in the post-War years had become alarming with a rise in prices of commodities, decrease in production of Indian industries, increase in burden of taxes and rents etc. Almost all sections of society suffered economic hardship due to the war and this strengthened the anti-British attitude. Post-First World War period also saw the preparation of the ground for common political action by Hindus and Muslims: (i) the Lucknow Pact (1916) had stimulated Congress- Muslim League cooperation; (ii) the Rowlatt Act agitation brought Hindus and Muslims, and also other sections of the society together; (iii) Radical nationalist Muslims like Mohammad Ali, Abul Kalam Azad, Hakim Ajmal Khan and Hasan Imam had now become more influential than the conservative Aligarh school elements who had dominated the League earlier. -

The Ideals of Islam in Maulana Abul Kalam Azad's Thoughts

The Ideals of Islam in Maulana Abul Kalam Azad‟s Thoughts 63 The Ideals of Islam in Maulana Abul Kalam Azad’s Thoughts and Political Practices: An Appraisal Dr. Misbah Umar Fozia Umar ** ABSTRACT The article attempts to explore and describe the ideals of Islam as perceived and practised by Maulana Abul Kalam Azad (1888-1958) at various stages of his life. Starting from religious conservatism received from his family, Maulana Azad moved towards rationalism at first and then to Pan-Islamism before finally committing to humanism. In this process of intellectual progression, his perception of Islam and its ideals changed as his social and political interactions changed over time. These changing contours of Maulana Azad‟s thoughts found manifestation in the political practices he carried out from various platforms. Islam served as a great source of legitimation in his political practices. Inspiration for Islamic revivalism drew him into political activities aimed at serving the Muslim cause and fighting British imperialism. Maulana Azad‟s sentiments and aspirations for Islam and Muslims echoed loudly during the Khilafat Movement which brought him closer to communal harmony and also resulted in his lasting association with the Indian National Congress. Whatever the platform he utilised, for Maulana Azad Muslim uplift remained a constant and prime concern in politics which he, ultimately, came to believe could be achieved by Hindu-Muslim unity as a single force against the British colonial power. Key Words: Islam, Pan-Islamism, Rationalism, Khilafat¸ Hijrat-ka-fatwa, Qaul-i-Faisal. Assistant Professor, Department of History, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan. -

Partition and Independence of India: 1924 Chair: Usama Bin Shafqat Committee Chair: Person ‘Year Director

Partition and Independence of India: 1924 Chair: Usama Bin Shafqat Committee Chair: Person ‘year Director: Partition and Independence of India: 1924 PMUNC 2015 Contents Chair’s Letter………………………………………………………...…..3 Short History……………………………………………………………..5 The Brief – 1924…………………………………………………………7 Sources to Consider……………………………………………………...8 Roles……………………………………………………………………..9 Maps……………………………………………………………………12 2 Partition and Independence of India: 1924 PMUNC 2015 Chair’s Letter Dear Delegates, Welcome to one of the most uniquely exciting committees at PMUNC 2015! My name is Usama Bin Shafqat and I will be your chair as we engage in a throwback to the events that continue to define lives for more than a billion people today. I am from Islamabad, Pakistan and will be a sophomore this year—tentatively majoring in Operations Research and Financial Engineering. Model UN has always been my IR indulgence in an otherwise scientific education as I culminated my high school career by serving as the Secretary-General for the largest conference in Islamabad—the Millennial Model UN 2013. I’ve continued Model UN here at Princeton by helping out with both PMUNC and PICSIM last year—in Operations and Crisis, respectively. Outside of Model UN, I’m a major foodie and love cricket. This will be a historical crisis committee where we chart our own path through a subcontinent where the British are fast losing grip over their largest colony. We shall convene in the 1920s as political parties within India begin engaging with the masses and stand up more forcefully against the British Empire. Our emphasis will be on the interplay between the major parties in the discussions—the British, the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League. -

Khilafat Movement and the Province of Sindh

KHILAFAT MOVEMENT AND THE PROVINCE OF SINDH Dr. Nasreen Afzal* KHILAFAT MOVEMENT AND THE PROVINCE OF SINDH ABSTRACT The Khilafat Movement started by the Muslims of India is directly related to the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire of Turkey, the only Muslim power of the world during the twentieth century, at the hands of different European nations and particularly against the hostile attitude of Britain towards Turkey . Like other areas of India Muslim s of Sindh played significant role in this movement. This article deals with the different efforts of Muslims of Sindh along with the Muslims of other areas for saving khlifat. Key words: Non violence non co-operation movement, Congress, Fatwas, Hijrat * Assistant Professor, Department of History , University of Karachi, Pakistan 51 Jhss, Vol. 1, No.1 , January to June 2010 The institution of Khilafat began after the death of Holy Prophet (P.B.U.H) in 632 AD when Hazrat Abu Bakr, who was the successor of the Holy Prophet, adopted the title of Khaltfatu-Rasool-i-illah , successor of Prophet of God. 1 The successor of Hazrat Abu Bakr, Hazrat Umar simplified the title to Khaltfah 2 and the Caliph (An English version of Khaltfah ) became temporal and spiritual head of the entire Muslims of the World. The first four caliphs were all selected democratically. However, after the death of Hazrat Ali, Amir Mu’awiyah laid down the foundation of Umayyad Dynasty, which changed the nature of Khilafat from democratic institution to monarchy. Umayyads and the rulers of the successive Muslim dynasties such as Abbasids, Fatimid (Egypt) and finally Ottomans (Turkey) continued to use the title of Caliph as used by four early Caliphs and further strengthening the institution of Khilafat, as a result Caliph became the symbolic head of the Muslim rule, even outside of Arabia. -

An Appraisal of Ubaid-Allah Sindhi's Mahabharat Sarvrajia Party And

Journal of Political Studies, Vol.20, Issue - 1, 2013, 159:177 A Voice from the Margins: An Appraisal of Ubaid-Allah Sindhi’s Mahabharat Sarvrajia Party and its Constitution Tanvir Anjum♣ Abstract Ubaid-Allah Sindhi is among those very few political thinkers and activists of the twentieth-century India who were initially associated with the traditional theological seminaries but their political vision was marked by liberalism and open- mindedness. He established a non-communal political party— Mahabharat Sarvrajia Party in 1924 in order to translate his political ideals into practice. The Party Constitution envisaged the idea of a unique form of confederal form of government for the country. It also presented an outline of a socio-economic order which was derived from a reconciliation of Socialist ideals with the Quran and Shah Wali-Allahi thought. However, he is among one of the least understood and often misinterpreted Muslim thinkers of India. Thus, there is a need to appreciate and reevaluate the political modernism in his thought and vision. Key-words: Ubaid-Allah Sindhi, Mahabharat Sarvrajia Party, The Constitution of the Federated Republics of India, Confederalism, Socialism Ubaid-Allah Sindhi (1872-1944) of Deoband School is among those very few political thinkers and activists who were trained in traditional madrassahs or theological seminaries, but had a thorough understanding of their contemporary political and economic ideologies, and were endowed with a deep vision and tremendous political foresight. Unlike most of his fellow ulama or scholars and political leaders of Deoband School, he was receptive to modernism, though in a selective manner. It is for this very reason that he has been hailed as ‘the most broad-minded Muslim scholar of South Asia after Shah Wali-Allah of Delhi’ by Said Ahmad Akbarabadi, an illustrious pupil of Sindhi and a renowned scholar of Islam (see introduction in Aslam, n.d., p. -

KAGK Memorial Lecture II Husain Haqqani

SecondSecond Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan MemorialMemorial Lecture Re-imagining Pakistan Husain Haqqani Former Ambassador of Pakistan to the United States Director, South & Central Asia, Hudson Institute Washington D.C Centre for Pakistan Studies MMAJ Academy of International Studies Jamia Millia Islamia The Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan Memorial Lecture instituted by the Centre for Pakistan Studies, MMAJ Academy of International Studies, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi in the memory of the legendary figure Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan is an initiative to propagate the values he stood for. Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, the great Pashtun leader is still remembered in India for his role in the national movement. The values he stood for still remain relevant for contemporary times. Born in Peshawar, North- West Frontier Province in 1890, he is known for his non-violent opposition to British rule during the final years of the Empire on the Indian sub-continent. In his early career, he wanted to uplift his fellow Pashtuns through the means of education. It was during his tireless work to organise and raise the consciousness of the Pashtuns that he came to be known as Badshah Khan, the ‘King of Chiefs.’ A lifelong pacifist and a follower of Mahatma Gandhi, he also came to be known as the ‘Frontier Gandhi.’ He was deeply influenced by Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence and forged a close, spiritual, and personal friendship with him. In 1929, he founded the Khudai Khidmatgar (Servants of God) known as the Red Shirt Movement among the Pashtuns. The Khudai Khidmatgar was founded on a belief in the power of Gandhi’s notion of Satyagraha.