Caring for Patients with Opioid Use Disorder in the Hospital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report

Research Report Revised Junio 2018 Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Table of Contents Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Overview How do medications to treat opioid use disorder work? How effective are medications to treat opioid use disorder? What are misconceptions about maintenance treatment? What is the treatment need versus the diversion risk for opioid use disorder treatment? What is the impact of medication for opioid use disorder treatment on HIV/HCV outcomes? How is opioid use disorder treated in the criminal justice system? Is medication to treat opioid use disorder available in the military? What treatment is available for pregnant mothers and their babies? How much does opioid treatment cost? Is naloxone accessible? References Page 1 Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Research Report Discusses effective medications used to treat opioid use disorders: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Overview An estimated 1.4 million people in the United States had a substance use disorder related to prescription opioids in 2019.1 However, only a fraction of people with prescription opioid use disorders receive tailored treatment (22 percent in 2019).1 Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids more than quadrupled from 1999 through 2016 followed by significant declines reported in both 2018 and 2019.2,3 Besides overdose, consequences of the opioid crisis include a rising incidence of infants born dependent on opioids because their mothers used these substances during pregnancy4,5 and increased spread of infectious diseases, including HIV and hepatitis C (HCV), as was seen in 2015 in southern Indiana.6 Effective prevention and treatment strategies exist for opioid misuse and use disorder but are highly underutilized across the United States. -

ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: 2020 Focused Update

The ASAM NATIONAL The ASAM National Practice Guideline 2020 Focused Update Guideline 2020 Focused National Practice The ASAM PRACTICE GUIDELINE For the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder 2020 Focused Update Adopted by the ASAM Board of Directors December 18, 2019. © Copyright 2020. American Society of Addiction Medicine, Inc. All rights reserved. Permission to make digital or hard copies of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for commercial, advertising or promotional purposes, and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the fi rst page. Republication, systematic reproduction, posting in electronic form on servers, redistribution to lists, or other uses of this material, require prior specifi c written permission or license from the Society. American Society of Addiction Medicine 11400 Rockville Pike, Suite 200 Rockville, MD 20852 Phone: (301) 656-3920 Fax (301) 656-3815 E-mail: [email protected] www.asam.org CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: 2020 Focused Update 2020 Focused Update Guideline Committee members Kyle Kampman, MD, Chair (alpha order): Daniel Langleben, MD Chinazo Cunningham, MD, MS, FASAM Ben Nordstrom, MD, PhD Mark J. Edlund, MD, PhD David Oslin, MD Marc Fishman, MD, DFASAM George Woody, MD Adam J. Gordon, MD, MPH, FACP, DFASAM Tricia Wright, MD, MS Hendre´e E. Jones, PhD Stephen Wyatt, DO Kyle M. Kampman, MD, FASAM, Chair 2015 ASAM Quality Improvement Council (alpha order): Daniel Langleben, MD John Femino, MD, FASAM Marjorie Meyer, MD Margaret Jarvis, MD, FASAM, Chair Sandra Springer, MD, FASAM Margaret Kotz, DO, FASAM George Woody, MD Sandrine Pirard, MD, MPH, PhD Tricia E. -

Medications for Opioid Use Disorder for Healthcare and Addiction Professionals, Policymakers, Patients, and Families

Medications for Opioid Use Disorder For Healthcare and Addiction Professionals, Policymakers, Patients, and Families UPDATED 2020 TREATMENT IMPROVEMENT PROTOCOL TIP 63 Please share your thoughts about this publication by completing a brief online survey at: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/KAPPFS The survey takes about 7 minutes to complete and is anonymous. Your feedback will help SAMHSA develop future products. TIP 63 MEDICATIONS FOR OPIOID USE DISORDER Treatment Improvement Protocol 63 For Healthcare and Addiction Professionals, Policymakers, Patients, and Families This TIP reviews three Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for opioid use disorder treatment—methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine—and the other strategies and services needed to support people in recovery. TIP Navigation Executive Summary For healthcare and addiction professionals, policymakers, patients, and families Part 1: Introduction to Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Treatment For healthcare and addiction professionals, policymakers, patients, and families Part 2: Addressing Opioid Use Disorder in General Medical Settings For healthcare professionals Part 3: Pharmacotherapy for Opioid Use Disorder For healthcare professionals Part 4: Partnering Addiction Treatment Counselors With Clients and Healthcare Professionals For healthcare and addiction professionals Part 5: Resources Related to Medications for Opioid Use Disorder For healthcare and addiction professionals, policymakers, patients, and families MEDICATIONS FOR OPIOID USE DISORDER TIP 63 Contents -

Pain and Opioid Dependence and Increasing Overdose Rates and Fatalities Along with Pharmacology of Buprenorphine

Patricia Pade, MD University of Colorado School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine CeDAR at the University of Colorado Hospital Richard Hoffman, MD Karen Cardon, MD Cynthia Geppert, MD University of New Mexico School of Medicine New Mexico Veterans Administration Health Care System Disclosures No Conflict of Interest to disclose The reported data is a clinical quality improvement project performed at the New Mexico VA Health Care System. Objectives To provide a brief overview of the epidemiology and prevalence of chronic pain and opioid dependence and increasing overdose rates and fatalities along with pharmacology of buprenorphine. To review and analyze data from a clinic integrating primary care pain management and opioid dependence to evaluate effectiveness of buprenorphine therapy. To describe the induction process and utilization of buprenorphine in the treatment of pain and opioid dependence in an outpatient setting along with the monitoring process to assess efficacy. Epidemiology Chronic Pain 116 million people in the US suffer with chronic pain – which is more than diabetes, cancer and heart disease combined1 35% American adults experience chronic pain Annual health care costs – expenses, lost wages, productivity loss estimated to be $635 billion1 Steady Increases in Opioid Prescriptions Dispensed by U.S. Retail Pharmacies, 1991-2011 Opioids Hydrocodone Oxycodone 250 219 210 201 202 200 192 180 169 158 151 144 150 139 131 120 109 100 96 91 100 86 80 76 78 50 Prescriptions (millions) Prescriptions 0 IMS’s Source -

Best Practices Across the Continuum of Care for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder

www.ccsa.ca • www.ccdus.ca Best Practices across the Continuum of Care for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder August 2018 Sheena Taha, PhD Knowledge Broker Best Practices across the Continuum of Care for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder This document was published by the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA). Suggested citation: Taha, S. (2018). Best Practices across the Continuum of Care for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder. Ottawa, Ont.: Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. © Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, 2018. CCSA, 500–75 Albert Street Ottawa, ON K1P 5E7 Tel.: 613-235-4048 Email: [email protected] Production of this document has been made possible through a financial contribution from Health Canada. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada. This document can be downloaded as a PDF at www.ccsa.ca. Ce document est également disponible en français sous le titre : Pratiques exemplaires dans le continuum des soins pour le traitement du trouble lié à l’usage d’opioïdes ISBN 978-1-77178-507-5 Best Practices across the Continuum of Care for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 2 Method................................................................................................................... -

Acute Pain Management for Inpatients with Opioid Use Disorder

2.5 HOURS CE Continuing Education Acute Pain Management for Inpatients with Opioid Use Disorder Overcoming misconceptions and prejudices. OVERVIEW: Like most hospital inpatients, those with opioid use disorder (OUD) often experience acute pain during their hospital stay and may require opioid analgesics. Unfortunately, owing to clinicians’ mis- conceptions about opioids and negative attitudes toward patients with OUD, such patients may be inade- quately medicated and thus subjected to unrelieved pain and unnecessary suffering. This article reviews current literature on the topic of acute pain management for inpatients with OUD and dispels common myths about opioids and OUD. Keywords: acute pain, addiction, evidence-based practice, opioid, opioid use disorder, pain, pain manage- ment, substance use disorder nna Barrett, a seasoned RN in the medical– Mr. Jackson notes that Ms. Somers has an order surgical unit of a busy urban hospital, is pro- for morphine 10 mg iv every four hours as needed A viding orientation training to Brian Jackson, for pain relief, in addition to a daily dose of morphine an RN who is new to the unit. (This scenario is a 100 mg iv by continuous infusion (4.2 mg per hour). composite based on actual events one of us, ZP, has Her last prn dose was two hours ago. Since she is observed in clinical practice.) Mr. Jackson has been not due for another for two hours, Mr. Jackson asks assigned to Beth Somers, a patient recovering from his colleague, Ms. Barrett, whether they can con- shoulder surgery. Her medical record includes a note tact the prescriber to increase the prn dosage or the about heroin abuse. -

Pain Management in Patients on Buprenorphine Maintenance

Managing Acute & Chronic Pain with Opioid Analgesics in Patients on Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) Daniel P. Alford, MD, MPH, FACP, FASAM Associate Professor of Medicine Assistant Dean, Continuing Medical Education Director, Clinical Addiction Research and Education Unit Boston University School of Medicine & Boston Medical Center 1 Daniel Alford, MD, Disclosures • Daniel Alford, MD, has no financial relationships to disclose. The contents of this activity may include discussion of off label or investigative drug uses. The faculty is aware that is their responsibility to disclose this information. 2 ASAM Lead Contributors, CME Committee and Reviewers Disclosure List Nature of Relevant Financial Relationship Name Commercial What was For what role? Interest received? Yngvild Olsen, MD, MPH None Adam J. Gordon, MD, MPH, None FACP, FASAM, CMRO, Chair, Activity Reviewer Edwin A. Salsitz, MD, Reckitt- Honorarium Speaker FASAM, Acting Vice Chair Benckiser James L. Ferguson, DO, First Lab Salary Medical Director FASAM Dawn Howell, ASAM Staff None 3 ASAM Lead Contributors, CME Committee and Reviewers Disclosure List, Continued Nature of Relevant Financial Relationship Name Commercial What was For what role? Interest received? Noel Ilogu, MD, MRCP None Hebert L. Malinoff, MD, Orex Honorarium Speaker FACP, FASAM, Activity Pharmaceuticals Reviewer Mark P. Schwartz, MD, None FASAM, FAAFP John C. Tanner, DO, Reckitt- Honorarium Speaker and consultant FASAM Benckiser Jeanette Tetrault, MD, None FACP 4 Accreditation Statement • The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians. 5 Designation Statement • The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) designates this enduring material for a maximum of one (1) AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. -

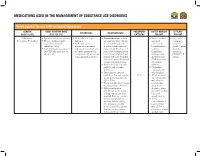

Medications Used in the Management of Substance Use Disorders

MEDICATIONS USED IN THE MANAGEMENT OF SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS Opioid Agonist Therapy (OAT) for Opioid Dependence GENERIC ADULT STARTING DOSE PREGNANCY SAFETY MARGIN EFFICACY ADVANTAGES DISADVANTAGES (BRAND NAME) (MAX PER DAY) CATEGORY FOR OAT FOR OAT Methadone • Specialty consultation advised. • Give orally in a single • Contraindications include • Serious overdose • First-line (Dolophine, Methadose) • Titrate carefully, consider daily dose. any situation where Opioids and death treatment methadone’s delayed • FDA approved for are contraindicated, such may occur if option for cumulative effects. detoxification treatment as patients with respiratory benzodiazepines, chronic Opioid • Individualize dosing regimens and maintenance treatment depression (in the absence of sedatives, dependence (AVOID same fixed dose for of Opioid dependence in resuscitative equipment or in tranquilizers, that meets all patients). conjunction with appropriate unmonitored situations) and antidepressants, DSM-IV-TR social and medical services. patients with acute bronchial alcohol or other criteria. asthma or hypercarbia, known CNS depressants or suspected paralytic ileus. are taken in • May prolong QTc intervals addition. on ECG; risk of cardiac • Methadone arrhythmias. contraindicated • Discontinue or taper the with selegiline. methadone dose and consider C/D • Avoid concurrent an alternative therapy if the use of methadone QTc > 500ms. with nilotinib, • Plasma half-life may be longer tetrabenazine, than the analgesic duration. ziprasidone, • Delayed analgesia or alcohol, st. johns toxicity may occur because wort, valerian, kava of drug accumulation after kava, and repeated doses, e.g., on days grapefruit juice. two to five; if patient has • Avoid excessive sedation during concurrent use of this timeframe, consider buprenorphine temporarily holding dose(s), with alcohol, st. lowering the dose, and/or johns wort, valerian slowing the titration rate. -

Opioid Use Disorder: Care for People 16 Years of Age and Older

Opioid Use Disorder Care for People 16 Years of Age and Older Summary This quality standard addresses care for people 16 years of age and older (including those who are pregnant) who have or are suspected of having opioid use disorder. The scope of this quality standard applies to all services and care settings, including long-term care homes, mental health settings, remote nursing stations, and correctional facilities, in all geographic regions of the province. Table of Contents About Quality Standards 1 How to Use Quality Standards 1 About This Quality Standard 2 Scope of This Quality Standard 2 Terminology Used in This Quality Standard 2 Why This Quality Standard Is Needed 3 Principles Underpinning This Quality Standard 4 How Success Can Be Measured 5 Quality Statements in Brief 6 Quality Statement 1: Identifying and Diagnosing Opioid Use Disorder 8 Quality Statement 2: Comprehensive Assessment and Collaborative Care Plan 10 Quality Statement 3: Addressing Physical Health, Mental Health, Additional Addiction Treatment Needs, and Social Needs 13 Quality Statement 4: Information to Participate in Care 17 Quality Statement 5: Opioid Agonist Therapy as First-Line Treatment 20 Quality Statement 6: Access to Opioid Agonist Therapy 23 Quality Statement 7: Treatment of Opioid Withdrawal Symptoms 27 Quality Statement 8: Access to Take-Home Naloxone and to Overdose Education 30 Quality Statement 9: Tapering Off of Opioid Agonist Therapy 33 Quality Statement 10: Concurrent Mental Health Disorders 37 Quality Statement 11: Harm Reduction 39 TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTINUED Emerging Practice Statement: Pharmacological Treatment Options for People With Opioid Use Disorder and Treatment Options for Adolescents 42 Acknowledgements 43 References 45 About Health Quality Ontario 48 About Quality Standards Health Quality Ontario, in collaboration with clinical experts, people with lived experience, and caregivers across the province, is developing quality standards for Ontario. -

Buprenorphine\Naloxone(BUP/NLX) Induction Flow Diagram

Opioid Use Disorder PATIENTS EXPERIENCE EVIDENCE RESEARCH Primary Care Pathway OUD (Patient willing to start treatment and may benefit from OAT) Consider Prescription Buprenorphine Methadone Opioid Misuse Index /Naloxone • Prescribing (POMI) if patient (Suboxone™) restrictions in receives prescription • Patient must be in withdrawal most provinces opioids and OUD is (12-24-hours opioid-free) If one fails, • Can be started immediately suspected. consider • Sublingual tablet the other. • Requires more observation Yes to >2 means (~10 minutes to dissolve) and time for dose adjustment diagnosis is more likely. Additional agents • Naloxone prevents IV diversion • Liquid formulation If not, it is less likely. available.† • May be started in office or at home DO YOU EVER: RETENTION IN TREATMENT Use your medication RETENTION IN TREATMENT* 73% versus 22% more often, (shorten the 64% versus 39% with no methadone time between doses), with placebo NNT = 2 than prescribed? NNT‡ = 4 Use more of your medication, (take a higher doses) than prescribed? Need early refills for your pain medications? Are psychosocial supports available? Feel high or get a buzz after using your pain medication? Yes, No, Take your pain medication because Offer to patient on OAT Opioid Agonist Therapy (OAT) you are upset, to relieve alone is still effective RETENTION IN TREATMENT or cope with problems other than pain? 74% with counselling RETENTION IN TREATMENT versus 62% no counselling with OAT alone versus Go to multiple 66% 22% NNT = 8 physicians /emergency on wait list for OAT NNT = 3 room doctors, seeking more of your pain medication? OAT is intended for long-term management. Optimal length of therapy is unknown. -

Acute Pain Management for Patients Receiving Maintenance Methadone Or Buprenorphine Therapy Daniel P

Annals of Internal Medicine Perspective Acute Pain Management for Patients Receiving Maintenance Methadone or Buprenorphine Therapy Daniel P. Alford, MD, MPH; Peggy Compton, RN, PhD; and Jeffrey H. Samet, MD, MA, MPH More patients with opioid addiction are receiving opioid agonist 4 common misconceptions resulting in suboptimal treatment of therapy (OAT) with methadone and buprenorphine. As a result, acute pain. Clinical recommendations for providing analgesia for physicians will more frequently encounter patients receiving OAT patients with acute pain who are receiving OAT are presented. who develop acutely painful conditions, requiring effective treat- Although challenging, acute pain in patients receiving this type of ment strategies. Undertreatment of acute pain is suboptimal med- therapy can effectively be managed. ical treatment, and patients receiving long-term OAT are at partic- ular risk. This paper acknowledges the complex interplay among Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:127-134. www.annals.org addictive disease, OAT, and acute pain management and describes For author affiliations, see end of text. he treatment of opioid dependence, both on heroin A 29-year-old woman reported severe right arm pain af- Tand prescription narcotics, with opioid agonist therapy ter fracturing her olecranon process. She had a history of in- (OAT) (that is, methadone or buprenorphine) is effective: jection heroin use and received methadone, 90 mg/d, in a It decreases opioid and other drug abuse, increases treat- methadone maintenance program. In the emergency depart- ment retention, decreases criminal activity, improves indi- ment, she seemed uncomfortable and received one 2-mg dose of vidual functioning, and decreases HIV seroconversion (1– intramuscular morphine sulfate over 6 hours. -

Pharmacological Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy

STAGEDN EMINARS IN P ERINATOLOGY 43 (2019) 141À148 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Seminars in Perinatology www.seminperinat.com Pharmacological treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy Christina E. Rodrigueza, and Kaylin A. Klieb,* aAlaska Native Medical Center, Anchorage, AK, USA bUniversity of Colorado, Department of Family Medicine, 1693 N Quentin Street, Aurora, CO, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Pharmacotherapy, or medication-assisted treatment (MAT), is a critical component of a comprehensive treatment plan for the pregnant woman with opioid use disorder (OUD). Methadone and buprenorphine are two types of opioid-agonist therapy which prevent withdrawal symptoms and control opioid cravings. Methadone is a long-acting mu-opioid receptor agonist that has been shown to increase retention in treatment programs and attendance at prenatal care while decreasing pregnancy complications. However metha- done can only be administered by treatment facilities when used for OUD. In contrast, buprenorphine is a mixed opioid agonist-antagonist medication that can be prescribed out- patient. The decision to use methadone vs buprenorphine for MAT should be individual- ized based upon local resources and a patient-specific factors. There are limited data on the use of the opioid antagonist naltrexone in pregnancy. National organizations continue to recommend MAT over opioid detoxification during pregnancy due to higher rates of relapse with detoxification. Ó 2019 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. tailor treatment to the unique needs of an individual pregnant Introduction woman. Pharmacotherapy, combined with individual counsel- ing, behavioral therapy, and group therapy gives pregnant For the vast majority of pregnant women with opioid use disor- women the best opportunity to achieve and maintain sobriety der (OUD), the use of pharmacotherapy as part of a comprehen- through pregnancy, immediately postpartum, and beyond.