165A Problems on Recording Statutes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIFORM REAL PROPERTY ELECTRONIC RECORDING ACT (Last Revised Or Amended in 2005)

UNIFORM REAL PROPERTY ELECTRONIC RECORDING ACT (Last Revised or Amended in 2005) drafted by the NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF COMMISSIONERS ON UNIFORM STATE LAWS and by it APPROVED AND RECOMMENDED FOR ENACTMENT IN ALL THE STATES at its ANNUAL CONFERENCE MEETING IN ITS ONE-HUNDRED-AND-THIRTEENTH YEAR PORTLAND, OREGON JULY 30-AUGUST 6, 2004 WITH PREFATORY NOTE AND COMMENTS Copyright ©2004 By NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF COMMISSIONERS ON UNIFORM STATE LAWS April 2005 ABOUT NCCUSL The National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (NCCUSL), now in its 114th year, provides states with non-partisan, well-conceived and well-drafted legislation that brings clarity and stability to critical areas of state statutory law. Conference members must be lawyers, qualified to practice law. They are practicing lawyers, judges, legislators and legislative staff and law professors, who have been appointed by state governments as well as the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to research, draft and promote enactment of uniform state laws in areas of state law where uniformity is desirable and practical. • NCCUSL strengthens the federal system by providing rules and procedures that are consistent from state to state but that also reflect the diverse experience of the states. • NCCUSL statutes are representative of state experience, because the organization is made up of representatives from each state, appointed by state government. • NCCUSL keeps state law up-to-date by addressing important and timely legal issues. • NCCUSL’s efforts reduce the need for individuals and businesses to deal with different laws as they move and do business in different states. -

Deed Recording

DEED RECORDING Deeds are important legal documents. The Onondaga County Clerk’s Office strongly recommends consulting an attorney regarding the preparation and filing/recording of any legal document. OUR OFFICE IS PROHIBITED BY LAW FROM PROVIDING ANY LEGAL ADVCE. THE ACCEPTANCE OF AN INSTRUMENT FOR RECORDING IN NO WAY IMPLIES AN ENDORSEMENT OR LEGAL SUFFICIENCY OR A GUARANTEE OF TITLE. IF YOU CHOOSE TO ACT AS YOUR OWN ATTORNEY YOU ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR LEGAL COMPLIANCE AND ANY IMPLICATIONS THEREOF. To find a local attorney who specializes in real estate, contact the Onondaga County Bar Association Lawyer Referral Serve at 315.471.2690. Their website is located at https://www.onbar.org/ Our office does not supply forms. To purchase a New York State specific deed form, you may visit the Blumberg Legal Forms website at: https://www.blumberg.com/forms/ All deed filings must be accompanied by both an RP-5217 and TP 584 All recording in Onondaga County require a legal description for the subject property. ADDITIONAL RECORDING FEE EFFECTIVE MARCH 11, 2020 Effective March 11, 2020 there will be a $10 fee added to all residential deed recordings. On January 11, 2020 Governor Cuomo signed into law an amendment to Real Property Law Section 291 that requires County Clerks to notify the owner(s) of record of residential real property when a document is recorded affecting said residential property. The law also allows a reasonable fee to be assessed for said notices. The NYS Association of County Clerks, in order to provide uniformity throughout NYS, has determined that $10 is a reasonable fee per document. -

Title Matters Affecting Parties in Possession: By

TITLE MATTERS AFFECTING PARTIES IN POSSESSION: ADVERSE POSSESSION, AFTER-ACQUIRED TITLE, & THE RULE AGAINST PERPETUITIES BY DONALD G. SINEX SCOTT C. PETRY SUSAN A. STANTON TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 I. ADVERSE POSSESSION…….……………………………………………………………. 1 1. Adverse Possession………...………………...……………………………………….......... 2 2. Identifying Issues in Record Title…………………………………………………………. 3 a. Historical Changes in Metes and Bounds…………………………………………… 4 b. Adverse Possession of Minerals……………………………………………………… 4 c. Adverse Possession in Cotenancy, Landlord-Tenant, & Grantor-Grantee Situations………………………………………………………………………….…...... 5 d. Distinguishing Coholders from Cotenants………………………………………….. 6 3. Adverse Possession Requirement………………………………………………………… 7 4. Other Issues………………………………………...……………………………………….. 9 II. AFTER ACQUIRED TITLE………………………….…………………………………………. 10 1. The Doctrine………………..……... ……………………………………………………….. 10 2. Bases Used by Courts in Applying the Doctrine…………………………………........... 11 3. Conveyance Instruments that an Examiner is Likely to Encounter…………………… 12 a. Deeds of Trust and Liens……………………………………………………………... 12 b. Oil & Gas Leases and Limitations……………………………………………………. 14 c. Public Lands……………………………………………………………………………. 15 d. Title Acquired in Trust………………………………………………………………… 16 e. Quitclaims and Limitations…………………………………………………………… 16 4. Effect on Notice and Purchasers………………………………………………………….. 18 a. Subsequent Purchaser…………………………………………………………………. 19 b. Protections……………………………………...………………………………………. 19 c. Duty to Search…………………………………………………………………………. -

July 2007 Real Property Question 6

July 2007 Real Property Question 6 MEE Question 6 Owen owned vacant land (Whiteacre) in State B located 500 yards from a lake and bordered by vacant land owned by others. Owen, who lived 50 miles from Whiteacre, used Whiteacre for cutting firewood and for parking his car when he used the lake. Twenty years ago, Owen delivered to Abe a deed that read in its entirety: Owen hereby conveys to the grantee by a general warranty deed that parcel of vacant land in State B known as Whiteacre. Owen signed the deed immediately below the quoted language and his signature was notarized. The deed was never recorded. For the next eleven years, Abe seasonally planted vegetables on Whiteacre, cut timber on it, parked vehicles there when he and his family used the nearby lake for recreation, and gave permission to friends to park their cars and recreational vehicles there. He also paid the real property taxes due on the land, although the tax bills were actually sent to Owen because title had not been registered in Abe’s name on the assessor’s books. Abe did not build any structure on Whiteacre, fence it, or post no-trespassing signs. Nine years ago, Abe moved to State C. Since that time, he has neither used Whiteacre nor given others permission to use Whiteacre, and to all outward appearances the land has appeared unoccupied. Last year, Owen died intestate leaving his daughter, Doris, as his sole heir. After Owen’s death, Doris conveyed Whiteacre by a valid deed to Buyer, who paid fair market value for Whiteacre. -

Virginia Real Property Electronic Recording Standard

SEC505-00.1 Effective Date: May 1, 2007 December 8, 2016 COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA Information Technology Resource Management Standard VIRGINIA REAL PROPERTY ELECTRONIC RECORDING STANDARD Virginia Information Technologies Agency (VITA) i Virginia Real Property Electronic Recording Standard SEC505-00.1 Effective Date: May 1, 2007 December 8, 2016 PUBLICATION VERSION CONTROL ITRM Publication Version Control: It is the user's responsibility to ensure they have the latest version of the ITRM publication. Questions should be directed to the Associate Director Manager for Policy, Practice and Enterprise Architecture (PPA) (EA) at VITA’s Relationship Management Governance (RMG) Strategic Management Services (SMS). SMS EA will issue a Change Notice Alert, post it on the VITA Web site, and provide an email announcement to the Circuit Court Clerks, as well as other parties PPA EA considers to be interested in the change. This chart contains a history of this ITRM publication’s revisions. Version Date Purpose of Revision Original 05/01/2007 Base Document This administrative update is necessitated by changes in the Code of 00.1 12/08/2017 Virginia and organizational changes in VITA. No substantive changes were made to this document. ii Virginia Real Property Electronic Recording Standard SEC505-00.1 Effective Date: May 1, 2007 December 8, 2016 PREFACE real estate settlement process for the benefit of citizens of the Commonwealth and users of the electronic Publication Designation filing system. SEC505-00.1 Sections 55-66.3 through 55-66.5 and 55-66.8 through Subject 55-66.15: This Standard for the electronic acceptance and recordation for the release of mortgage, rescinding Virginia Real Property Electronic Recording Standard erroneously recorded certificates of satisfaction, requirements on secured creditors, and the form and Effective Date effect of satisfaction facilitates real estate transactions May 1, 2007 December 8, 2016 in the Commonwealth. -

Usufruct Study Guide

Article 562 ± 578 1. Define usufruct. Usufruct is a real right by virtue of which a person is given the right to enjoy the property of another with the obligation of preserving its form and substance, unless the title constituting it or the law provides otherwise. 2. What are the three fundamental Rights Appertaining to Ownership? Ownership consists of three fundamental rights, to wit: - jus disponende (right to dispose) - jus utendi (right to use) - jus fruendi (right to the fruits) 3. Of the above-mentioned fundamental rights, what consists usufruct and naked ownership? The combination of the jus utendi and jus fruendi is called usufruct. The remaining right jus disponendi is really the essence of what is termed ³naked ownership´. 4. What right is transferred to the usufructuary and what right is remained with the owner? In a usufruct, only the jus utendi and jus fruendi over the property is transferred to the usufructuary. The owner of the property maintains the jus disponendi or the power to alienate, encumber, transform, and even destroy the same. (Hemedes vs. CA, 316 SCRA 347 1999). 5. What are the formulae with respect to full ownership, usufruct, and naked ownership? The following are the formulae: - Full Ownership equals Naked Ownership plus Usufruct - Naked Ownership equals Full Ownership minus Usufruct - Usufruct equals Full Ownership minus Naked Ownership 6. What are the characteristics or elements of usufruct? The following are the characteristics or elements of usufruct: ESSENTIAL CHARACTERISTICS: those without which it can not be termed usufruct: (a) It is REAL RIGHT (whether registered in the Registry of Property or not). -

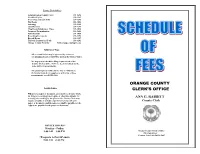

Schedule of Fees (PDF)

County Clerk Offices Administration/County Clerk 291-2690 Certified Copies 291-3287 Court Papers/Court Calls 291-3286 File Room 291-3086 Indexing 291-3285 Land Records 291-3287 Map Room/Subdivision Maps 291-3084 Passports/Naturalization 291-2698 Pistol Permits 291-3060 Recording Documents 291-3292 Record Room 291-3287 Uniform Commercial Code 291-3292 Orange County Web Site www.orangecountygov.com Subdivision Maps After a subdivision map is approved by a town or city planning board, it MUST be filed in the Clerk’s Office. We urge you to check the filing requirements of the County Clerk’s Office that have been mandated by the state and local governments. The planning board office in the city or town where the land is located can supply you with a list of these requirements, or call 291-3084. ORANGE COUNTY Legible Copies CLERK’S OFFICE Whenever a paper or document, presented to a County Clerk for filing or recording is not legible or otherwise suitable for ANN G. RABBITT scanning or recording by the process, the County Clerk may require a legible or suitable copy thereof along with such County Clerk paper or document, and the same fees shall be payable for the copy as are payable for the paper or document. OFFICE HOURS * Monday – Friday 9:00 AM – 5:00 PM Orange County Clerk’s Office 255 Main Street Goshen, New York 10924-1697 *Passports & Pistol Permits 9:00 AM – 4:30 PM ASSIGNMENT OF MORTGAGE*, To Record 45.00 MECHANICS LIEN, To File 15.00 Plus Per Page 5.00 Affidavit of Service (35 Days) 5.00 Plus Each Additional Mortgage 3.00 Discharge by Payment into Court 3.00 1st Asst. -

Recording Deeds in Lake County

Recording Deeds in Lake County Deeds for properties located in Lake County should be recorded in the Lake County Recorder of Deeds Office. Deeds are accepted for recording in person or by mail. Once recorded, the document will be assigned a document number, scanned, and entered into a Grantor/Grantee index. The original document will be returned to the party named on the document. After recording, land records are available for public viewing. As always, it is suggested that you consult legal & accounting professionals to fully understand the legal & tax implications of recording any property deed changes. If there is anything that our staff can do to help make this process easier for you, please let us know. 18 N County St – 6th Floor Waukegan, IL 60085-4358 Phone: (847) 377-2575 Fax: (847) 984-5860 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lakecountyil.gov/recorder Recording Requirements: 1. Deeds must be dated, signed & notarized. 2. Parties involved must be named. 3. Grantee's (buyer) address must be listed. 4. Deeds require a complete legal description. 5. Metes & bounds legal descriptions require a Plat Act affidavit. 6. Deeds require the name & address of the Preparer. 7. Deeds require “Mail to” information (name & address) - this is where the recorded document must be returned, after it has been recorded. 8. Taxpayer name & address for tax bills must be listed. 9. All deeds require either a completed Illinois PTAX- 203 form or a signed & dated exemption statement. 10. Local municipal transfer tax stamps must be obtained at the local municipality prior to being submitted to the Recorder of Deeds Office. -

Condominium Ownership of Real Property

CHAPTER 47-04.1 CONDOMINIUM OWNERSHIP OF REAL PROPERTY 47-04.1-01. Definitions. In this chapter, unless context otherwise requires: 1. "Common areas" means the entire project excepting all units therein granted or reserved. 2. "Condominium" is an estate in real property consisting of an undivided interest or interests in common in a portion of a parcel of real property together with a separate interest or interests in space in a structure, on such real property. 3. "Interest" means the fractional or percentage interest or interests ascribed to each unit by the declaration provided for in section 47-04.1-03. 4. "Limited common areas" means those elements designed for use by the owners of one or more but less than all of the units included in the project. 5. "Project" means the entire parcel of real property divided, or to be divided into condominiums, including all structures thereon. 6. "To divide" real property means to divide the ownership thereof by conveying one or more condominiums therein but less than the whole thereof. 7. "Unit" means the elements of a condominium which are not owned in common with the owners of other condominiums in the project. 47-04.1-02. Recording of declaration to submit property to a project. When the sole owner or all the owners, or the sole lessee or all of the lessees of a lease desire to submit a parcel of real property to a project established by this chapter, a declaration to that effect shall be executed and acknowledged by the sole owner or lessee or all of such owners or lessees and shall be recorded in the office of the recorder of the county in which such property lies. -

Application for the Registration of a Public Offering Statement for a Residential Condiminium

AP P LICATION FOR THE REGISTRATION OF A P UBLIC OFFERING STATEMENT FOR A RESIDENTIAL CONDOMINIU M Office of the Secretary of State State House Annapolis, MD 21401 Revised 7/2017 APPLICATION FOR THE REGISTRATION OF A PUBLIC OFFERING STATEMENT FOR A RESIDENTIAL CONDIMINIUM The Maryland Condominium Act1 requires a Public Offering Statement for all residential condominiums being offered for sale in Maryland to be registered with the Office of the Secretary of State regardless of the location of the condominium. A contract for the initial sale of a condominium unit may not be entered into until the Public Offering Statement for the proposed condominium regime has been registered with the Secretary of State and until ten days after all amendments to the Public Offering Statement have been filed with the Secretary of State. An application for the registration of a condominium located in Maryland consists of a Public Offering Statement as described herein and in §11-126 of the Maryland Condominium Act, completed in accordance with the application form attached hereto, and a registration fee of $5.00 per unit, but not less than $100.00. In the case of a condominium located wholly outside of Maryland, an application that has been approved by an agency in the State where the condominium is located and that substantially complies with the Maryland Condominium Act may be submitted to the Secretary of State for registration. If the application has been approved by that out-of- state agency, please use the Maryland application to cross-reference to the approved documents. Certification of approval from the state agency which approved the documents must also be included. -

Quitclaim Holder As a Bona Fide Purchaser

Wyoming Law Journal Volume 6 Number 4 Article 7 December 2019 Quitclaim Holder as a Bona Fide Purchaser Neil McLean Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uwyo.edu/wlj Recommended Citation Neil McLean, Quitclaim Holder as a Bona Fide Purchaser, 6 WYO. L.J. 306 (1952) Available at: https://scholarship.law.uwyo.edu/wlj/vol6/iss4/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Law Archive of Wyoming Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wyoming Law Journal by an authorized editor of Law Archive of Wyoming Scholarship. WYOMING LAW JOURNAL This proposition immediately poses many problems beyond the scope of this article, but it is apparently the best solution to date of conserving present oil and gas resources. MElVIN M. FILLERUP QUITCLAIM HOLDER AS A BONA FIDE PURCHASER On the question whether one claiming under a quitclaim is entitled to the protection of the recording acts there is a wide range of authority. Text writers have divided the authorities into so-called majority and minority rules, with the majority giving the quitclaim grantee the protec- tion of the recording acts.' Also the majority view is gaining favor con- stantly, the minority rule denying such protection being an outdated viewpiont.2 However, beneath the facade of majority and minority labels, there appears to be a large number of subsidiary rules, with no such clear-cut differences as would seem indicated. This article will attempt to point out the barely discernible basic reasoning behind the welter of conflicting rules. A theory which can be disposed of initially is one finding that presence or lack of warranties in a deed has bearing upon the problem, whether we shall recognize the good faith of a quitclaim holder by granting him protection against outstanding unrecorded interests. -

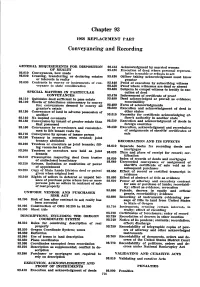

Conveyancing and Recording

Chapter 93 1968 REPLACEMENT BART Conveyancing and Recording GENERAL REQUIREMENTS FOR DISPOSITION 93415 Acknowledgment by married woman OF REALTY 93420 Execution of deed where personal represen 93010 Conveyances how made tative is unable or refuses to act 93020 Creating transferring or declaring estates 93430 Officer taking acknowledgment must know or interests in realty grantor 93030 Contracts to convey or instruments of con 93440 Proof of execution by subscribing witness veyance to state consideration 93450 Proof where witnesses are dead or absent 93460 Subpena to compel witness to testify to exe SPECIAL MATTERS IN PARTICULAR cution of deed CONVEYANCES 93470 Indorsement of certificate of proof 93110 Quitclaim deed sufficient to pass estate 93480 Deed acknowledged or proved as evidence 93120 Words of inheritance unnecessary to convey recordability fee conveyances deemed to convey all 93490 Form of acknowledgments grantors estate 93500 Execution and acknowledgment of deed in 93130 Conveyance of land in adverse possession of other states another 93510 Necessity for certificate acknowledging of 93140 No implied covenants ficers authority in another state 93150 Conveyance by tenant of greater estate than 93520 Execution and acknowledgment of deeds in that possessed foreign countries 93160 Conveyance by reversioners and remainder 93530 Execution acknowledgment and recordation men to life tenant vests fee of assignments of sheriffs certificates of 93170 Conveyance by spouse of insane person sale 93180 Tenancy in common when created joint tenancy