Mamidipudi.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adaptation of the List of Backward Classes Castes/ Comm

GOVERNMENT OF TELANGANA ABSTRACT Backward Classes Welfare Department – Adaptation of the list of Backward Classes Castes/ Communities and providing percentage of reservation in the State of Telangana – Certain amendments – Orders – Issued. Backward Classes Welfare (OP) Department G.O.MS.No. 16. Dated:11.03.2015 Read the following:- 1. G.O.Ms.No.3, Backward Classes Welfare (OP) Department, dated.14.08.2014 2. G.O.Ms.No.4, Backward Classes Welfare (OP) Department, dated.30.08.2014 3. G.O.Ms.No.5, Backward Classes Welfare (OP) Department, dated.02.09.2014 4. From the Member Secretary, Commission for Backward Classes, letter No.384/C/2014, dated.25.9.2014. 5. From the Director, B.C. Welfare, Telangana, letter No.E/1066/2014, dated.17.10.2014 6. G.O.Ms.No.2, Scheduled Caste Development (POA.A2) Department, Dt.22.01.2015 *** ORDER: In the G.O. first read above, orders were issued adapting the relevant Government Orders issued in the undivided State of Andhra Pradesh along with the list of (112) castes/communities group wise as Backward Classes with percentage of reservation, as specified therein for the State of Telangana. 2. In the G.O. second and third read above, orders were issued for amendment of certain entries at Sl.No.92 and Sl.No.5 respectively in the Annexure to the G.O. first read above. 3. In the letters fourth and fifth read above, proposals were received by the Government for certain amendments in respect of the Groups A, B, C, D and E, etc., of the Backward Classes Castes/Communities as adapted in the State of Telangana. -

Prospectus for Admission to Three-Year Ll.B

Government of Kerala PROSPECTUS FOR ADMISSION TO THREE-YEAR LL.B. COURSE, KERALA 2021-22 Approved as per G.O(MS)NO. /2021/HEDN dated: .0 .2021. Office of the Commissioner for Entrance Examinations Housing Board Buildings, Santhinagar Thiruvananthapuram – 695001 Phone: 0471-2525300 Fax 0471-2337228 www.cee.kerala.gov.in PROSPECTUS FOR ADMISSION TO THREE YEAR LL.B COURSE, KERALA 2021-22 1. Prospectus for admission to the Three-year LL.B course 2021-22 approved by Govt. of Kerala is published herewith. The Prospectus issued in earlier years is not valid for 2021-22 2. This is a course leading to the Bachelor’s Degree in Law in conformity with rules framed by the Bar Council of India by virtue of its powers under the Advocates Act, 1961. The degree obtained after successful completion of the course shall be recognised for the purpose of enrolment as Advocate under the Advocates Act, 1961. 3. The course shall consist of a regular course of study for a minimum period of three academic years. The last 6 months of the final year of the course shall include regular course of practical training. 4. The course of study in Law shall be by regular attendance for the requisite number of lectures, tutorials, moot courts and other practical training. 5. Admission to the course will be regulated on the basis of merit as assessed in the Entrance Examination to be conducted by the Commissioner for Entrance Examinations (CEE). 6. Eligibility for Admission (i) Nativity: Applicant should be an Indian Citizen. However, only those candidates who are of Kerala origin are eligible for any type of reservation or any fee concession. -

HYDERABAD NOTIFICATION NO. 54/2017 Dt. 21/10/2017 TEACHER

TELANGANA STATE PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION: HYDERABAD NOTIFICATION NO. 54/2017 D t . 2 1 / 1 0 / 2 0 1 7 TEACHER RECRUITMENT TEST IN SCHOOL EDUCATION DEPARTMENT LANGUAGE PANDIT (GENERAL RECRUITMENT) PARA – I: 1) Applications are invited Online from qualified candidates through the proforma Application to be made available on Commission’s WEBSITE (www.tspsc.gov.in ) to the post of Language Pandit in School Education Department. i. Submission of ONLINE applications from Dt. 30/10/2017 ii. Last date for submission of ONLINE applications Dt. 30/11/2017 iii. Hall Tickets can be downloaded 07 days before commencement of Examination. 2) The Examination (Objective Type) is likely to be held in 2 nd Week of February 2018. The Commission reserves the right to conduct the Examination either COMPUTER BASED RECRUITMENT TEST (CBRT) or OFFLINE OMR based Examination of objective type. The Candidates will have to apply Online through the Official Website of TSPSC. Detailed user guide will be placed on the website. The candidates will have to thoroughly read before filing Online applications. IMPORTANT NOTE: Candidates are requested to keep the details of the following documents ready while uploading their Applications. (i) Aadhar number (ii) Educational Qualification details i.e., SSC, INTERMEDIATE, DEGREE, POST GRADUATION etc. and their Roll numbers, Year of passing etc. (iii) Community/ Caste Certificate obtained from Mee Seva/ E Seva i.e., Enrollment number and date of issue. 3) The candidates who possess requisite qualification may apply online by satisfying themselves about the terms and conditions of this recruitment. The details of vacancies are given below:- Age as on Sl. -

Andhra Pradesh Public Service Commission

1 ANDHRA PRADESH PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION: HYDERABAD NOTIFICATION NO.22/2016, Dt.17/12/2016 CIVIL ASSISTANT SURGEONS IN A.P.INSURANCE MEDICAL SERVICE (GENERAL RECRUITMENT) PARA – 1: Applications are invited On-line for recruitment to the post of Civil Assistant Surgeons in A.P. Insurance Medical Service. The proforma Application will be available on Commission’s Website (www.psc.ap.gov.in) from 23/12 /2016 to 22/01/2017 (Note:22/01/2017 is the last date for payment of fee up- to 11:59 mid night). Before applying for the post, an applicant shall register his/her bio-data particulars through One Time Profile Registration (OTPR) on the Commission Website viz., www.psc.ap.gov.in. Once applicant registers his/her particulars, a User ID is generated and sent to his/her registered mobile number and email ID. Applicants need to apply for the post using the OTPR User ID through Commission’s website. The Commission conducts Screening test in Off - Line mode in case applicants exceed 25,000 in number and main examination in On-Line mode for candidates selected in screening test. If the screening test is to be held, the date of screening test will be communicated through Commission’s Website. The Main Examination is likely to be held On-Line through computer based test on 03/03/2017 FN & AN. There would be objective type questions which are to be answered on computer system. Instructions regarding computer based recruitment test are attached as Annexure - III. MOCK TEST facility would be provided to the applicants to acquaint themselves with the computer based recruitment test. -

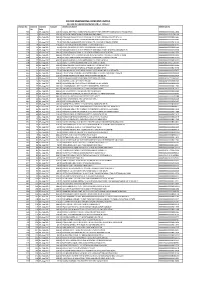

Elecon Engineering Company Limited Details of Unpaid Dividend for F.Y

ELECON ENGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED DETAILS OF UNPAID DIVIDEND FOR F.Y. 2016-17 Cheque No Warrant Warrant Amount Beneficiary Name Reference No No Date 580 1 05-Aug-2017 120.00 KAWAL JEET GILL C O BRIG SPS GILL DEPUTY GEN OFFICER COMMANDING HQ 24 INFAN 0000000000000K011604 581 2 05-Aug-2017 150.00 JAI SINGH RAWAT 4488 PUNJAB AND SIND BANK 00001201910101709134 585 6 05-Aug-2017 480.00 KAMLESH JAGGI C O SHRI T N JAGGI B 471 NEW FRIENDS COLONY MATHU 0000000000000K011985 588 9 05-Aug-2017 120.00 SATYAKAM C O RITES 27 BARAKHAMBA ROAD ROOM NO 605 NEW DELHI HOUSE 0000000000000S013492 590 11 05-Aug-2017 75.00 PRANOB CHAKRABORTY EMTICI ENG LTD 418 WORLD TRADE CENTRE 0000000000000P010194 593 14 05-Aug-2017 120.00 VEENA AHUJA 18 KHAN MARKET FLATS NEW DELHI 0000000000000V010147 594 15 05-Aug-2017 25.00 RAMA CHANDRA ACHARYA 233 JOR BAGH NEW DELHI 0000000000000R001546 595 16 05-Aug-2017 120.00 SANSAR CHAND SUD 1815 SECOND FLOOR UDAI CHAND M KOTLA MUBARAKPUR 0000000000000S013338 598 19 05-Aug-2017 160.00 PARSHOTAM LAL BAJAJ 1C 29 NEW ROHTAK ROAD NEW DELHI 0000000000000P011250 603 24 05-Aug-2017 480.00 VAIKUNTH NATH SHARMA 2 1786 NEAR BHAGIRATH PALACE CHANDNI CHOWK 0000000000000V011321 605 26 05-Aug-2017 80.00 MUKESH KAPOOR 506 KRISHNA GALI KATRA NEEL CHANDNI CHOWK 0000000000000M012161 606 27 05-Aug-2017 600.00 MOHD ASHEQIN C O GULAB TRADING CO 5585 S B DELHI 0000000000000M012009 608 29 05-Aug-2017 62.50 SHASHI CHOPRA 01190005348 STATE BANK OF INDIA 0000IN30039415130730 609 30 05-Aug-2017 120.00 USHA MATHUR 144 PRINCESS PARK PLOT NO 33 SECTOR 6 0000000000000U010436 -

Prospectus.Pdf

CONTENTS Clause ITEM Page No. Clause ITEM Page No. Introduction 1 3 9 Certificates/Documents to be uploaded 12 along with the Application 2 Institutions and Intake 3 10 Entrance Examination 13 3 Categorization of Seats 3 11 Centralized Allotment Process(CAP) & 15 Online Submission of Options 4 Fee Structure 3 12 Post Allotment activities 20 5 Eligibility for Admission 3 13 Preventive measures against Ragging 22 6 Reservation of Seats 4 14 No Liquidated Damages 22 7 Claim for Reservation 6 15 Other Items 23 8 How and When to Apply 10 Page No. Page No. Annexure No. No. Annexure List of college that participated in CAP 24 Proforma for Non-Creamy Layer I 2020-21 VIII Certificate for SEBC Candidates 37 List of Socially and Educationally Proforma for community Certificate II 28 Backward Classes(SEBC) IX for SC/ST Candidates 38 Proforma for anti-ragging verdict for III 30 List of Scheduled Castes (SC) X all candidates 39 IV 31 Certificate to be produced by the List of Scheduled Tribes (ST) XI applicants belonging to AAY and PHH 40 category List of Other Eligible Communities V(a) 32 (OEC) Income and assets certificate to be XII 41 List of communities eligible for produced by EWS V(b) 33 education concession as is given to OEC XIII Guidelines for images to be uploaded 42 Proforma for Income & Community VI 34 Certificate for SEBC Candidates XIV Instructions for filling OMR Answer sheet 43 35 VII Proforma for Inter-caste Marriage Certificate XV District Facilitation Centres 45 Page 2 MCA-2021,(C)DTE,TVPM PROSPECTUS FOR ADMISSION TO MCA COURSE 2021-22 1. -

List of SC/ST/OEC & SEBC Community (Annexure

ANNEXURE – VI LIST OF SCHEDULED CASTES (Reservation Group : SC) [As Amended by The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Orders (Second Amendment) Act, 2002 (Act 61 of 2002) Vide Part VIII – Kerala - Schedule 1 Notified in the Gazette of India dated 18.12.2002, The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order (Amendment) Act 2007, The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order (Amendment) Act 2016, No. 24 of 2016] [See Clause 5.4.3 a)] 1 Adi Andhra 37 Mannan (മാൻ), Pathiyan, Perumannan, 2 Adi Dravida Peruvannan, Vannan, Velan 3 Adi Karnataka 38 xxx 4 Ajila 39 Moger (other than Mogeyar) 5 Arunthathiyar 40 Mundala 6 Ayyanavar 41 Nalakeyava 7 Baira 42 Nalkadaya 8 Bakuda 43 Nayadi 9 xxx 44 xxx 10 Bathada 45 Pallan 11 xxx 46 Palluvan, Pulluvan 12 Bharathar (Other than Parathar), Paravan 47 Pambada 13 xxx 48 Panan 14 Chakkiliyan 49 xxx 15 Chamar, Muchi 50 Paraiyan, Parayan, Sambavar, Sambavan, Sambava, Paraya, Paraiya, Parayar 16 Chandala 17 Cheruman 51 xxx 18 Domban 52 xxx 19 xxx 53 xxx 20 xxx 54 Pulayan, Cheramar, Pulaya, Pulayar, Cherama, Cheraman, Wayanad Pulayan, Wayanadan Pulayan, 21 xxx Matha, Matha Pulayan 22 Gosangi 55 xxx 23 Hasla 56 Puthirai Vannan 24 Holeya 57 Raneyar 25 Kadaiyan 58 Samagara 26 Kakkalan, Kakkan 59 Samban 27 Kalladi 60 Semman, Chemman, Chemmar 28 Kanakkan, Padanna, Padannan 61 Thandan (excluding Ezhuvas and Thiyyas who are known as Thandan, in the erstwhile Cochin and 29 xxx Malabar areas) and (Carpenters who are known as 30 Kavara (other than Telugu speaking or Tamil Thachan, in the erstwhile Cochin and Travancore speaking Balija Kavarai, Gavara, Gavarai, Gavarai State) Thachar (Other than carpenters) Naidu, Balija Naidu, Gajalu Balija or Valai Chetty) 62 Thoti 31 Koosa 63 Vallon 32 Kootan, Koodan 64 Valluvan 33 Kudumban 65 xxx 34 Kuravan, Sidhanar, Kuravar, Kurava, Sidhana 66 xxx 35 Maila 67 Vetan 36 Malayan [In the areas comprising the Kannur, 68 Vettuvan, Pulaya Vettuvan (in the areas of Kasaragode, Kozhikode and Wayanad Districts]. -

Prospectus for Admission to Ll.M Course, Kerala 2021-22

Government of Kerala PROSPECTUS FOR ADMISSION TO LL.M COURSE, KERALA 2021-22 Office of the Commissioner for Entrance Examinations Housing Board Buildings, Santhinagar Thiruvananthapuram – 695001 Phone: 0471-2525300 Fax:0471-2337228 www.cee-kerala.org PROSPECTUS FOR ADMISSION TO LL.M COURSE 2021-22 IN THE LAW COLLEGES IN KERALA The Prospectus for admission to the LL.M Course 2021-22, approved by Government of Kerala is published herewith. The prospectus issued in earlier years is not valid for the academic year 2021-22. 1. This course leads to the Master’s Degree in Law. 2. The course shall consist of a regular course of study for a minimum period of two academic years. 3. The Post Graduate course of study in Law shall be by regular attendance, home assignments, test papers, seminars and preparation of dissertations in the respective branch of specialisation. 4. Academic Eligibility for Admission Candidates who have passed the LL.B. examination (5 year / 3 year course) with a minimum of 50% marks from the Universities in Kerala or other Universities recognised by the Universities in Kerala as equivalent thereto are eligible for admission. No rounding off of percentage of marks to the nearest higher integer is permitted. Candidates appearing / appeared for the regular Final Year LL.B. examination can also apply for the Entrance Examination. Such candidates become eligible for admission only if they produce the Provisional / Degree Certificate of the qualifying examination and the mark lists of all parts of the qualifying examination at the time of Centralised Allotment Process (CAP). 5. Nativity A candidate applying for this course shall be an Indian Citizen. -

Telangana State Public Service Commission: Hyderabad Notification No

TELANGANA STATE PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION: HYDERABAD NOTIFICATION NO. 10/2017 TRAINED GRADUATE TEACHERS IN RESIDENTIAL EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS SOCIETIES (GENERAL RECRUITMENT) PARA – I: 1) Applications are invited Online from qualified candidates through the proforma Application to be made available on Commission’s WEBSITE (www.tspsc.gov.in ) to the post of Trained Graduate Teachers in Residential Educational Institutions Societies i. Submission of ONLINE applications from Dt. 10/02 /2017 ii. Last date for submission of ONLINE applications Dt. 04/03/2017 iii. Hall Tickets can be downloaded 07 days before commencement of Examination. iv. The question paper of Preliminary (Screening Test) and Main examination will be supplied in English version only except languages. 2) The Preliminary (Screening Test) is likely to be held on Dt. 19/03/2017 and the Main Examination (Objective Type) is likely to be held on 30/04/2017 F.N AND 30/04/2017 A.N. The Commission reserves the right to conduct the Examination either COMPUTER BASED RECRUITMENT TEST (CBRT) or OFFLINE OMR based Examination of objective type. Before applying for the posts, candidates shall register themselves as per the One Time Registration (OTR) through the Official Website of TSPSC. Those who have registered in OTR already shall apply by login to their profile using their TSPSC ID and Date of Birth as provided in OTR. 3) The candidates who possess requisite qualification may apply online by satisfying themselves about the terms and conditions of this recruitment. The details of vacancies are given below:- Age as on Scale of Sl. No. of Name of the Post 01/07/2017 Pay No. -

Monograph Series, Ugadi, Part VII-B, Vol-I

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 MONOGRAPH SERIES VOLUME I PART VII-B UGADI THE NEW YEAR'S FESTIVAL OF ANDHRA PRADESH MONOGRAPH No. 4 OFFICE OF THE REri~iltAif1.tENERAL, INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS NEW DELHI-II Stenography H. MANCHANDA Typing B. N. KAPOOR Proof Reading S. P. JAIN Cover Page S. K. PILLA} (vii) CONTENTS Pages Foreword .. (v) Preface ( viii) Chapter I INTRODUCTION (A) Prelude 1-2 (B) Particulars of the villages and the communities studied 2-5 Chapter II GENERAL FEATURES OF THE FESTIVAL (A) Significance of the time when Ugadi is performed 7 (B) Mythological sanction for the festival 7 (C) A look at the ritual complex 7-8 (D) Preparation for Ugadi 8-9 (E) The Ugadi day in a typical household in the villages of East Godavari and West Godavari districts Chapter III A CLOSER LOOK AT THE DIFFERENT ASPECTS OF UGADI (A) Core of the sacred occasion 11 (B) Ugadi Pachadi 11-12 (C) Offering of Java 12 (D) First ploughing ceremony 12-13 (E) Taking stock of the divine ordinance for the next year 13-15 (F) Capitalising the auspicious day 15-16 (G) Mystic linkage of the rites of the sacred occasion 16 (H) Highlight on some of the important variations 16-17 (a) Regional variations 16 (b) Inter-village variations in the performance of Ugadi 16 (c) Role of caste in the performance of Ugadi 16-17 Chapter IV UGADI AT FAMILY LEVEL (A) Awareness about the reason for performance of the festival 19 (B) Purchase of new clothes 19-20 (C) Collection of ritual objects 20 (iii) Pales (D) Collection of special food items 20-21 (E) Tasting of Ugadi Pachadi • 21-22 -

List of Reservation Communities Formatted.Doc

LIST OF SOCIALLY AND EDUCATIONALLY BACKWARD CLASSES (SEBC) [Vide G.O.(P) 208/66/Edn. dated 02-5-1966] [See Clause 9 (b)] I. Ezhavas including Ezhavas, Thiyyas, Ishuvan, Izhuvan, Illuvan and Billava II. Muslims (all sections following Islam) III. Latin Catholics other than Anglo-Indians IV. Other Backward Christians (a) SIUC (b) Converts from Scheduled Castes to Christianity V. Other Backward Hindus, i.e. 1. Agasa 2. Arayas including Valan, Mukkuvan, Mukaya, Mogayan, Arayan, Bovies, Kharvi, Nulayan, and Arayavathi 3. Aremahrati 4. Arya including Dheevara/Dheevaran Atagara, Devanga, Kaikolan, (Sengunthar) Pattarya, Saliyas (Padmasali, Pattusali, Thogatta, Karanibhakatula, Senapathula, Sali, Sale, Karikalabhakulu, Chaliya) Sourashtra, Khatri, Patnukaran, Illathu Pillai, Illa Vellalar, Illathar 5. Bestha 6. Bhandari or Bhondari 7. Boya 8. Boyan 9. Chavalakkaran 10. Chakkala (Chakkala Nair) 11. Devadiga 12. Ezhavathi (Vathi) 13. Ezhuthachan, Kadupattan 14. Gudigara 15. Galada Konkani 16. Ganjam Reddies 17. Gatti 18. Gowda 19. Ganika including Nagavamsom 20. Hegde 21. Hindu Nadar 22. Idiga including Settibalija 23. Jangam 24. Jogi 25. Jhetty 26. Kanisu or Kaniyar-Panicker, Kaniyan, Kanisan, Kannian or Kani, Ganaka 27. Kudumbi 28. Kalarikurup or Kalari Panicker 29. Kerala Muthali 30. Kusavan including Kulala, Kumbaran, Odan, Oudan (Donga) Odda (Vodde or Vadde or Veddai) Velaan, Andhra Nair, Anthuru Nair. 31. Kalavanthula 32. Kallan including Isanattu Kallar 33. Kabera 34. Korachas 35. Kammalas including Viswakarmala, Karuvan, Kamsalas, Viswakarmas, Pandikammala, Malayal-Kammala, Kannan, Moosari, Kalthachan, Kallasari, Perumkollen, Kollan, Thattan, Pandithattan, Thachan, Asari, Villasan, Vilkurup, Viswabrahmins, Kitara, Chaptegara. 36. Kannadiyans 37. Kavuthiyan 38. Kavudiyaru 39. Kelasi or Kalasi Panicker 40. Koppala Velamas 41. Krishnanvaka 42. Kuruba 43. -

PART III COMPENDIUM of INSTRUCTIONS ISSUED on RESERVATION for OTHER BACKWARD CLASSES in SERVICES/POSTS UNDER the GOVERNMENT of INDIA Page 1

PART III COMPENDIUM OF INSTRUCTIONS ISSUED ON RESERVATION FOR OTHER BACKWARD CLASSES IN SERVICES/POSTS UNDER THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Page 1. o.M:. No. 36012/31/90- Estt. (Sen. dated 13-8-90 437 2. OM. No. 36012/31I9O-Estt. (SCl), dated 25-9-91 438 3. OM. No. 36012/2,193-Estt.(SCl), dated 2-2-93 439 4. OM. No. 3602214193-Estt. (SCl), dated 1-6-93 440 5. OM. No. 36012/24/93-Estt. (SCl), dated 7-6-93 441 6. OM. No. 3602214193-Estt. (SCl), dated 25-6-93 442 7. OM. No. 36022/23I93-Estt. (Sen. dated 22-7-93 443 8. OM. No. 36022/13193-Estt. (SCl), dated 30-7-93 444 9. O.M. No. 36012/37193-Estt. (SCl), dated 19-8-93 445 10. OM. No. 36012/37193-Estt. (Sen. dated 19-8-93 446 11. OM. No. 36012122193-Estt.(Sen. dated 8-9-93 447 12. Resolution No. 1201l/68/93-BCC(C). dated 10-9-93 on Castes/Communities 453 13. OM. No. 36012/22/93-Estt.(SCl), dated 22-10-93 482 14. Letter No. 36012f22193-Estt. (SCl), dated 15-11-93 to Chief Secretaries of StateslUnion Territories 485 15. OM. No. 36012122193-Estt. (SCl), dated 15-11-93 491 16. OM. No. 3fi014/2193-Estt. (SCl), dated 20-12-93 493 17. OM. No. 36012122193-Estt.(Sen. dated 29-12-93 494 18. OM. No. 36012122193-Estt. (SCl), dated 30-12-93 S03 No. 36012/3119O-Estt. (seT) Government of India MInJJtry of Penonnel, PubUe Grievances " Pensions (Department of Personnel " Training) New Delhi, the 13th August, 1990.