Using Liquidated Damages in Comparable Coaches' Contracts to Assess a School's Economic Damage from the Loss of a Successful Coach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men's Basketball Coaching Records

MEN’S BASKETBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 NCAA Division I Coaching Records 4 Coaching Honors 31 Division II Coaching Records 36 Division III Coaching Records 39 ALL-DIVISIONS COACHING RECORDS Some of the won-lost records included in this coaches section Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. have been adjusted because of action by the NCAA Committee 26. Thad Matta (Butler 1990) Butler 2001, Xavier 15 401 125 .762 on Infractions to forfeit or vacate particular regular-season 2002-04, Ohio St. 2005-15* games or vacate particular NCAA tournament games. 27. Torchy Clark (Marquette 1951) UCF 1970-83 14 268 84 .761 28. Vic Bubas (North Carolina St. 1951) Duke 10 213 67 .761 1960-69 COACHES BY WINNING PERCENT- 29. Ron Niekamp (Miami (OH) 1972) Findlay 26 589 185 .761 1986-11 AGE 30. Ray Harper (Ky. Wesleyan 1985) Ky. 15 316 99 .761 Wesleyan 1997-05, Oklahoma City 2006- (This list includes all coaches with a minimum 10 head coaching 08, Western Ky. 2012-15* Seasons at NCAA schools regardless of classification.) 31. Mike Jones (Mississippi Col. 1975) Mississippi 16 330 104 .760 Col. 1989-02, 07-08 32. Lucias Mitchell (Jackson St. 1956) Alabama 15 325 103 .759 Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. St. 1964-67, Kentucky St. 1968-75, Norfolk 1. Jim Crutchfield (West Virginia 1978) West 11 300 53 .850 St. 1979-81 Liberty 2005-15* 33. Harry Fisher (Columbia 1905) Fordham 1905, 16 189 60 .759 2. Clair Bee (Waynesburg 1925) Rider 1929-31, 21 412 88 .824 Columbia 1907, Army West Point 1907, LIU Brooklyn 1932-43, 46-51 Columbia 1908-10, St. -

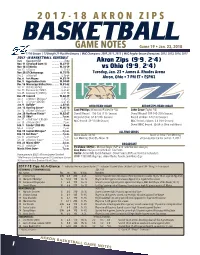

2017-18 Akron Zips Game Notes

2017-18 AKRON ZIPS BASKETBALL GAME NOTES Game 19 • Jan. 23, 2018 117th Season | 12-Straight 21-Plus Win Seasons | MAC Champions: 2009, 2011, 2013 | MAC Regular-Season Champions: 2012, 2013, 2016, 2017 2017 -18 BASKETBALL SCHEDULE Date Opponent (TV) ...................Time Akron Zips (9-9, 2-4) Nov. 11 Cleveland State (1) .......... W, 67-57 Nov. 18 UT Martin .......... W, 76-59 vs Ohio (9-9, 2-4) Nov. 25 at Dayton .................L, 73-60 Nov. 28 UT Chattanooga .......... W, 75-70 Tuesday, Jan. 23 • James A. Rhodes Arena Dec. 2 at Marshall .................L, 86-64 Dec. 6 Fort Wayne .......... W, 83-79 Akron, Ohio • 7 PM ET • ESPN3 Dec. 9 Appalachian State .......... W, 94-89 Dec. 16 Mississippi Valley State .......... W, 81-62 Dec. 22 USC (#) ((ESPNU) .................L, 84-53 Dec. 23 Princeton (#) (ESPN3) .................L, 64-62 Dec. 25 Davidson (#) (ESPNU) .................L, 91-78 Dec. 29 Concord .......... W, 86-49 Jan. 2 at Western Michigan* .................L, 87-75 Jan. 5 at Toledo* (CBS-SN) .................L, 67-65 Jan. 9 Buffalo* ............L, 87-65 OHIO HEAD COACH AKRON ZIPS HEAD COACH Jan. 13 Bowling Green* .......... W, 80-78 Jan. 16 at Eastern Michigan* .................L, 63-49 Saul Phillips (Wisconsin-Platteville ‘96) John Groce (Taylor ‘94) Jan. 20 Northern Illinois* .......... W, 82-67 Overall Record: 196-136 (11th Season) Overall Record: 189-140 (10th Season) Jan. 23 Ohio* .............. 7 p.m. Record at Ohio: 62-52 (4th Season) Record at Akron: 9-9 (First Season) Jan. 27 at Ball State* (CBS-SN) ..................... Noon Jan. 30 at Miami (OH)* ....................7 p.m. -

2008-09 Morehead State Men's Basketball Postseason Edition

•~ __, m Morehead State .. Morehead State Athletic Media Relations: Men's Basketball • Randy Stacy- MBB Contac t ... 606-783-2500 .. [email protected] 2008-09 2008-09 Schedule .. Record: 20-1 SI OVC: 12-6 Morehead State (20· 1SJ vs. Louisville (28-5) ... Home: 1 2-1 / Road: 4-12 / Neutral: 4-2 March 20, 2009 · Dayton, Ohio-7:10 p.m. EDT Date Opoaneot Time/Result UD Arena- NCAA Tournament First Round ... Noy 14 at ULM 56-54 fll Gome 36-CBS NOY· 1.6 at Vanderbilt•• 74-48 II ... Noy. 19 at Drake** 86-70 Multimedia Information The Series The Coaches Nov 22 at L musvllle:t:• .. L 79-41 Radio: WIVY- FM 96.3 and the Eagle Louisville leads 28-12 In a series that Morehead State .. Noy. 23 I 79-74 Sports Network dates to 1931· 32. Morehead State has not Donnie iyndall Nov 29 GrambtlngA I 72-71 Web Audio: www.ncaaspor ts.com beate;i Louisville since 1957. The Cardi (Morehead State, 1993) ... liveStats: www,ncaasports.com nals won the earlier meeting this season, MSU/ Career Record: 47-48 (]rd year) Noy 30 UCF" {CBS-CS) W 71-65 Television: CBS 79-41, In Loulsv1lle . MSU Media Contact: ... Dec 4 W 80-71 Next Game Louisville Randy Stacy Rick Pltlno Pee 6 Mucrav State• w, 79-74 [email protected] The winner of tonight's game will advance (Massachusetts, 1974) to the second round of the NCAA Tourna UofL Record: 197-72 (6 years) .. Dec. 11 at 1mno1s State L 76-7Q ment to take the winner of the Ohio State Career Record: 549-196 (21 years) . -

La Salle Basketball Media Guide 2003-04 La Salle University

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons La Salle Basketball Media Guides University Publications 2003 La Salle Basketball Media Guide 2003-04 La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/basketball_media_guides Recommended Citation La Salle University, "La Salle Basketball Media Guide 2003-04" (2003). La Salle Basketball Media Guides. 66. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/basketball_media_guides/66 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in La Salle Basketball Media Guides by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2003-04 Media Guide J $sT "I have known Billy Hahn for many, many years and" he brings a world of enthusiasm and energy to. the game. He has a great passion and is a r - ° --•• ' great asset to La Salle. basJMbaH..^ [ ' -*'' "* ."••*:. - ~ • "T". :::::; - DlCk Uit3l6* fSP^y/lfen?o//^pas/feffta//yi/ia/ysf ; ; : s "Billy Hahn's energy', and "passion for La Salle will make this program a* winner. How can, it .... hot? Just watch him on the sidelines. He cares j . so deeply about turning the. Explorers into a j." winner that ;his work ethic Jias, to pay,,off. The : stable .of underclassmen is of thei richest " K^r^E^H^B one^ in the Explorers will likely/ move- higher m^the* Midmati ESPN/ESPN.cMcollegeiBaskeWalliC&lumhist- ~ 1p «%r : tJJ'X opponen t. His team; much like himself, gives it all every trip, every game. -

CONFERENCE CALLS ATLANTIC COAST CONFERENCE Monday (January 4-March 8) 10:30 A.M

CONFERENCE CALLS ATLANTIC COAST CONFERENCE Monday (January 4-March 8) 10:30 a.m. ET ............Al Skinner, Boston College 10:40 a.m. ET ............Oliver Purnell, Clemson 10:50 a.m. ET ............Mike Krzyzewski, Duke 11:00 a.m. ET ............Leonard Hamilton, Florida State 11:10 a.m. ET ............Paul Hewitt, Georgia Tech 11:20 a.m. ET ............Gary Williams, Maryland 11:30 a.m. ET ............Frank Haith, Miami 11:40 a.m. ET ............Roy Williams, North Carolina 11:50 a.m. ET ............Sidney Lowe, N.C. State 12:00 p.m. ET ............Tony Bennett, Virginia 12:10 p.m. ET ............Seth Greenberg, Virginia Tech 12:20 p.m. ET ............Dino Gaudio, Wake Forest ATLANTIC 10 CONFERENCE Monday (January 4-March 15) 10:10 a.m. ET ............Bobby Lutz, Charlotte 10:17 a.m. ET ............Chris Mooney, Richmond 10:24 a.m. ET ............Chris Mack, Xavier 10:31 a.m. ET ............Mark Schmidt, St. Bonaventure 10:38 a.m. ET ............Brian Gregory, Dayton 10:45 a.m. ET ............John Giannini, La Salle 10:52 a.m. ET ............Fran Dunphy, Temple 10:59 a.m. ET ............Derek Kellogg, Massachusetts 11:06 a.m. ET ............Karl Hobbs, George Washington 11:13 a.m. ET ............Ron Everhart, Duquesne 11:20 a.m. ET ............Rick Majerus, Saint Louis 11:27 a.m. ET ............Jared Grasso, Fordham 11:34 a.m. ET ............Jim Baron, Rhode Island 11:41 a.m. ET ............Phil Martelli, Saint Joseph’s BIG EAST CONFERENCE Thursday (Jan. 7, Jan. 21, Feb. 4, Feb. 18) 11:00 a.m. ET ............Jay Wright, Villanova 11:08 a.m. -

2007 January-December

For Immediate Release Morehead State Athletic Media Relations Women's Basketball 112/07 Contact: Matt Schabert (606) 783-2500 Women's Basketball Knocks Off Tennessee State, 68-55 MOREHEAD, Ky. - Host Morehead State got seasons highs of 14 points from freshman Amanda Green and junior Tarah Combs and cashed in 28 points off 2~ Tennessee State turnovers to defeat the Tigers, 68-55, Tuesday, at Johnson Arena. With the win, the Eagles' second straight, MSU moved to 4-9 overall and 3-2 in the Ohio Valley Conference, while TSU fell to 3-8 and 1-2 in the conference. Green and Combs both equaled their season highs with the 14 points. Combs dropped in a trio of three-pointers in 22 minutes on the floor, while Green scored in double figures for the third consecutive game. The Eagles also got a third straight double-double from senior LaKrisha Brown with 12 points and 10 rebounds. Freshman Brandi came off the bench in the second half and scored nine points and added a career high 11 rebounds, including eight on the offensive glass. Junior guard Stacey Strayer dished out a career high eight assists. Tennessee State got a game high 18 points from Meesha Jackson, while Nikki Rumph had 13 and Oby Okafor added 12. LaDona Pierce paced TSU with five assists. Morehead State got off to a slow start, trailing 16-13 with 6:05 left in the first half, but the Eagles went on a 12-2 run - capped by a three-pointer by senior Jessie Plante - to lead 25-18 with 56 seconds left. -

Californmen's Basketball

GAME 3: SAN DIEGO STATE CALIFORNIA men's basketball Assistant Director of Athletic Communications (Men’s Basketball contact): Mara Rudolph Cell: (510) 384-6574• Email: [email protected] • Twitter: @MaraRudolph7 Website: CalBears.com • Facebook: Facebook.com/CalMensBball • Twitter: @CalMensBball • Instagram: @CalMensBball SCHEDULE #25/RV CALIFORNIA vs. San Diego State RV SAN DIEGO STATE OVERALL: 2-0 • PAC-12: 0-0 GOLDEN BEARS (2-0) AZTECS (2-1) HOME: 2-0 • AWAY: 0-0 • NEUTRAL: 0-0 Date ...............Monday, Nov. 21 Time .................................8 p.m DATE OPPONENT TIME Venue ............. Golden 1 Center NOV. 3 CAL BAPTIST (EXH) W, 81-73 Location ......Sacramento, Calif. NOV. 11 SOUTH DAKOTA STATE W, 82-53 TV ....................Pac-12 Network NOV. 16 UC IRVINE W, 75-65 (OT) (Ted Robinson, Mike Montgomery) Nov. 21 vs. San Diego St.% (P12N) 8 p.m. Radio ..California Golden Bears NOV. 25 WYOMING (P12N) 8 P.M. Sports Network - KGO 810 AM NOV. 27 SOUTHEAST LOUISIANA (P12N) 5 P.M. (Todd McKim, Jay John) NOV. 30 LOUISIANA TECH (P12N) 6 P.M. Live Stats ............ CalBears.com DEC. 3 ALCORN STATE (P12N) 1 P.M. Dec. 6 vs. Princeton^ (FS1) TBD Dec. 7 vs. Seton Hall^ (FS1) TBD DEC. 10 UC DAVIS (P12N) 7:30 P.M. After grinding out a tough overtime win sans three starters Wednesday night, California men’s DEC. 17 CAL POLY (P12N) 5 P.M. basketball hits the road for its first neutral-site contest of the season, a Monday night matchup with DEC. 21 VIRGINIA (ESPN2) 7 P.M. San Diego State. The Golden Bears and Aztecs meet at the brand new Golden 1 Center, home of the DEC. -

2020-21 Men's Basketball Almanac

Southern Miss 2020-21 Men’s Basketball Almanac Quick Facts General Team Information Table of Contents School: University of Southern Mississippi 2019-20 Record: 9-22 General Information Conference USA Preferred Name: Southern Miss Home / Away / Neutral: 8-7 / 1-12 / 0-3 Media Information 2 Standings 38 Location: Hattiesburg, Miss. Conference Record: 5-13 Media Outlets 3 Awards 38 Founded: 1910 Home / Away / Neutral: 4-5 / 1-8 / 0-0 IMG College 3 Team Records 39 Enrollment: 14,845 Conference Finish: 13th / 14 Season Outlook Individual Records Nickname: Golden Eagles Final Rankings: N/A Preview 4 Top-10 Individuals 40-42 School colors: Black and Gold Starters Returning / Lost: 2 / 3 Roster 5 1,000-Point Club 43-44 Arena: Reed Green Coliseum Letterwinners Returning / Lost: 6 / 9 Schedule 5 Records at a Glance 45 Capacity: 8,095 Newcomers: 9 Photo Roster 6 Scoring 46-48 Affiliation: NCAA Division I Rebounding 49 Conference: Conference USA Coaching Staff Student-Athlete Profiles Field Goals 49 President: Dr. Rodney Bennett Head Coach: Jay Ladner Tyler Morman 7 Three-Point Field Goals 50 Denijay Harris 7 Free Throws 50 Alma Mater: Middle Tennessee, 1990 Alma Mater: Southern Miss, 1988 Justin Johnson 8 Assists 51 Athletics Director: Jeremy McClain Southern Miss Record: 9-22 (second season) Angel Smith 8 Steals 51 Alma Mater: Delta State, 1999 Career Record: 85-110 (seventh season) Blake Roberts 9 Blocks 51 Faculty Athletic Representative: Dr. Alan Thompson Associate Head Coach: Kyle Roane DeAndre Pinckney 9 Games 51 Alma Mater: Texas State, 1991 -

South Carolina State (2-2) 2019-20 Record: 3-1 Date Opponent Time • Result Head Coach: Jerry Stackhouse 11.1 Clark Atlanta (Exhibition)

Vanderbilt Commodores Vanderbilt Commodores (3-1) vs. Vanderbilt Commodores South Carolina State (2-2) 2019-20 Record: 3-1 Date Opponent Time • Result Head Coach: Jerry Stackhouse 11.1 Clark Atlanta (Exhibition) .................... W, 95-55 VUCommodores.com Career Record: 81-34 (2) 11.6 Southeast Missouri State ..................... W, 83-65 Twitter • @VandyMBB VU Record: 3-1 (1) 11.11 Texas A&M Corpus-Christi .................... W, 71-66 Instagram • @VandyMBB 2019-20 LEADERS 11.14 Richmond ................................................ L, 92-93 OT Facebook • VanderbiltAthletics Points: Aaron Nesmith (26.5) 11.20 Austin Peay ........................................ W, 90-72 In-Game Notes • @VandyNotes Rebounds: Clevon Brown (6.3) 11.22 South Carolina State .................. 7 p.m. (SECN+) Assists: Saben Lee (7.3) 11.25 Southeastern Louisiana ............. 7 p.m. (SECN+) Blocks: Clevon Brown (1.8) 11.30 Tulsa ........................................ 7 p.m. (SECN+) Nov. 22, 2019 • 8 p.m. CT 12.3 Buffalo ..................................... 7 p.m. (SECN+) Memorial Gym • Nashville, Tenn. • 14,316 South Carolina State 12.14 Liberty ..................................... 7 p.m. (SECN+) 2019-20 Record: 2-2 Murray Garvin 12.18 Loyola-Chicago (Phoenix, Ariz.) ...5:30 p.m. (CBSSN) SEC Network+ Head Coach: 12.21 UNC Wilmington ........................ 7 p.m. (SECN+) Kevin Ingram (play-by-play), Shan Foster (analyst) Career Record: 72-134 (8) 12.30 Davidson .................................. 7 p.m. (SECN+) S. Carolina State Record: 72-134 (8) 1.4 SMU ...........................................8 p.m. (SECN) WLAC 1510 AM / WNRQ FM 98.3 2018-19 LEADERS 1.8 Auburn ................................................. 8 p.m. (SECN) Joe Fisher (play-by-play), Tim Thompson (analyst) Points: Zacchaeus Sellers (15.0) 1.11 Texas A&M............................. -

Akron Zips (15-4, 5-1 MAC) Vs Ohio Bobcats (10-9, 2-4 MAC)

Game Notes 20: vs Ohio BASKETBALL 119th Season | MAC Champions: 2009, 2011, 2013 | MAC Regular-Season Champions: 2012, 2013, 2016, 2017 2019 -20 BASKETBALL SCHEDULE Date Opponent TV .............. Time Akron Zips (15-4, 5-1 MAC) Nov. 5 Malone ........W, 81-64 Nov. 8 West Virginia AT&T Sports ......L, 94-84 vs Ohio Bobcats (10-9, 2-4 MAC) Nov. 15 N.C. Central (%) ESPN3 ....W, 57-47 Nov. 18 S.C. Upstate (%) ESPN+ ...W, 76-45 Saturday, Jan. 25 • Convocation Center Nov. 21 Youngstown State (%) ESPN+ W, 82-60 Athens, Ohio • 3:30 PM • ESPN3 Nov. 24 Louisville (%) ...............L, 82-76 Nov. 29 Merrimack ........W, 64-47 Dec. 4 Marshall .............W, 85-73 Dec. 8 Southern ........W, 72-57 Dec. 15 Concord ......W, 100-50 Dec. 20 Tulane (#) .............W, 62-61 Dec. 21 Liberty (#) ...............L, 80-67 OHIO HEAD COACH AKRON ZIPS HEAD COACH Dec. 30 UMASS ESPN3 ....W, 85-79 Jeff Boals John Groce Jan. 4 *Eastern Michigan ESPN+ .......W, 69-45 (Ohio ‘95) (Taylor ‘94) Jan. 7 *Western Michigan ESPN+ ...W, 84-69 Overall: 65-50 (4th season) Career Record: 226-169 (12th Season) Jan. 10 *Ball State CBSSN....W, 75-60 Record at Ohio: 10-9 (1st season) Record at Akron: 46-38 (3rd Season) Jan. 14 *Northern Illinois ESPN+ .......W, 72-49 MAC Record: 2-4 (1st season) MAC Record at Akron: 19-23 (3rd Season) Jan. 18 *Toledo ESPN3 ..... L, 99-89 Jan. 21 *Miami ESPN+ .......W, 81-60 Overall MAC Record: 53-53 (at Ohio and Akron) Jan. 25 *Ohio ESPN3 ........3:30 pm ALL-TIME SERIES Jan. -

IN the UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS for the FIRST CIRCUIT No. 19-2005 STUDENTS for FAIR ADMISSIONS, INC., Plaintiff-Appellant

Case: 19-2005 Document: 00117592653 Page: 1 Date Filed: 05/21/2020 Entry ID: 6340661 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT No. 19-2005 STUDENTS FOR FAIR ADMISSIONS, INC., Plaintiff-Appellant, PRESIDENT AND FELLOWS OF HARVARD COLLEGE, Defendant-Appellee. On Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts Case No. 1:14-cv-14176-ADB BRIEF OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BASKETBALL COACHES, WOMEN’S BASKETBALL COACHES ASSOCIATION, GENO AURIEMMA, JAMES A. BOEHEIM, JOHN CHANEY, TOM IZZO, MICHAEL W. KRZYZEWSKI, JOANNE P. MCCALLIE, NOLAN RICHARDSON, BILL SELF, SUE SEMRAU, ORLANDO “TUBBY” SMITH, TARA VANDERVEER, ROY WILLIAMS, JAY WRIGHT, AND 326 ADDITIONAL CURRENT OR FORMER COLLEGE HEAD COACHES AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEE AND AFFIRMANCE William Evans* (application for Jaime A. Santos admission forthcoming) Sabrina M. Rose-Smith (application for GOODWIN PROCTER LLP admission forthcoming) 100 Northern Avenue GOODWIN PROCTER LLP Boston, MA 02210 100 N Street, N.W. Tel.: (617) 570-1000 Washington, D.C. 20036 [email protected] Tel.: (202) 346-4000 [email protected] [email protected] Dated: May 21, 2020 Counsel for Amici Curiae Case: 19-2005 Document: 00117592653 Page: 2 Date Filed: 05/21/2020 Entry ID: 6340661 CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT Pursuant to Rule 26.1 of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, counsel for Amici Curiae certifies as follows: • The National Association of Basketball Coaches has no parent corporation, and no company holds 10 percent or more of its stock. • The Women’s Basketball Coaches Association has no parent corporation, and no company holds 10 percent or more of its stock. -

ILLINOIS BASKETBALL GUIDE CHAMPAIGN " 1995/96 "Ifntrf.!*^

1796.32363 .116 1995/96 CENTENNIAL ,W' T Iv^A .OM,%j i E^l^ iwd-yo ngniing mini Daa»K.evDaii i\o^t^ra» Alph abetical umerical Mo. Player Ht. Wt. Yr. Pos. Hometown/High School No. Player 44 Ryan Blackwell F 6-8 207 Fr. Pittsford.N.Y./Pittsford-Sutheriand 21 Matt Heldman 45 Chris Gandy** F 6-9 207 Jr. Kankakee, lll./Bradley-Bourbonnais Kiwane Garris 22 Kiwane Garris** G 6-2 183 Jr. Chicago, Ill./Westinghouse Richard Keene 32 Jerry Gee* F 6-8 239 So. Chicago, Ill./St. Martin De Porres Bryant Notree 21 Matt Heldman* G 6-0 162 So. Libertyville, lll./Libertyville Brett Robisch 40 Jerry Hester** F 6-6 194 Jr. Peoria, lll./Manual Jerry Gee 34 Brian Johnson* F 6-6 196 So. Des Plaines, lll./MaineWest Kevin Turner 24 Richard Keene*** G 6-6 205 Sr. Collinsville, Ill./Collinsville Brian Johnson 25 Bryant Notree* G 6-5 205 So. Chicago, Ill./Simeon Jerry Hester 31 Brett Robisch* C 6-11 239 So. Springfield, Ill./Calvary Ryan Blackwell 33 Kevin Turner* G 6-2 162 So. Chicago, Ill./Simeon Chris Gandy Letters Earned I I The 1995-96 University of Illinois men's basketball team front row (left to right): Head Coach Lou Henson, Assistant Coach Jimmy Collins, Bryant Notree, Kiwane Garris, Matt Heldman, Kevin Turner, Richard Keene, Assistant Coach Mark Bial and Administrative Assistant Scott Frisina. Back row (left to right) Trainer Rod Cardinal, Jerry Hester, Jerry Gee, Chris Gandy, Brett Robisch, Ryan Blackwell, Brian Johnson and Assistant Coach Dick Nagy.