'T: Ottawa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Psychological Approach to Musical Form: the Habituation–Fluency Theory of Repetition

A Psychological Approach to Musical Form: The Habituation–Fluency Theory of Repetition David Huron With the possible exception of dance and meditation, there appears to be nothing else in common human experience that is comparable to music in its repetitiveness (Kivy 1993; Ockelford 2005; Margulis 2013). Narrative arti- facts like movies, novels, cartoon strips, stories, and speeches have much less internal repetition. Even poetry is less repetitive than music. Occasionally, architecture can approach music in repeating some elements, but only some- times. There appears to be no visual analog to the sort of trance–inducing music that can engage listeners for hours. Although dance and meditation may be more repetitive than music, dance is rarely performed in the absence of music, and meditation tellingly relies on imagining a repeated sound or mantra (Huron 2006: 267). Repetition can be observed in music from all over the world (Nettl 2005). In much music, a simple “strophic” pattern is evident in which a single phrase or passage is repeated over and over. When sung, it is common for successive repetitions to employ different words, as in the case of strophic verses. However, it is also common to hear the same words used with each repetition. In the Western art–music tradition, internal patterns of repetition are commonly discussed under the rubric of form. Writing in The Oxford Companion to Music, Percy Scholes characterized musical form as “a series of strategies designed to find a successful mean between the opposite extremes of unrelieved repetition and unrelieved alteration” (1977: 289). Scholes’s characterization notwithstanding, musical form entails much more than simply the pattern of repetition. -

Modeling the Dishabituation Hierarchy: the Role of the Primordial Hippocampus*

Biol. Cybern. 67, 535-544 (1992) Biological Cybemetics Springer-Verlag 1992 Modeling the dishabituation hierarchy: The role of the primordial hippocampus* DeLiang Wang and Michael A. Arbib Center for Neural Engineering, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089-2520, USA Received January 30, 1992/accepted in revised form April 6, 1992 Abstract. We present a neural model for the organiza- orienting response to a certain stimulus applied at a tion and neural dynamics of the medial pallium, the given location, the response can be released by the same toad's homolog of mammalian hippocampus. A neural stimulus applied at a different retinal locus (Eikmanns mechanism, called cumulative shrinking, is proposed 1955; Ewert and Ingle 1971). (2) Hierarchical stimulus for mapping temporal responses from the anterior tha- specificity. Another stimulus given at the same locus lamus into a form of population coding referenced by may restore the response habituated by a previous spatial positions. Synaptic plasticity is modeled as an stimulus. Only certain stimuli can dishabituate a previ- interaction of two dynamic processes which simulates ously habituated response. Ewert and Kehl (1978) acquisition and both short-term and long-term forget- demonstrated that this dishabituation forms a hierarchy ting. The structure of the medial pallium model plus the (Fig. 1A), where a stimulus can dishabituate the habitu- plasticity model allows us to provide an account of the ated responses of another stimulus if the latter is lower neural mechanisms of habituation and dishabituation. in the hierarchy. Computer simulations demonstrate a remarkable match A model developed by Wang and Arbib (1991a) between the model performance and the original exper- showed how a group of cells in the anterior thalamus imental data on which the dishabituation hierarchy was (AT) could respond to stimuli higher in the hierarchy based. -

Journal of Neurobiology, Parametric Studies of The

JOURNAL OF NEUROBIOLOGY,VOL. 1, NO. 3, PP. 345-360 PARAMETRIC STUDIES OF THE RESPONSE DECREMENT PRODUCED BY MECHANICAL STIMULI IN THE PROTOZOAN, Stentor coeruleus DAVID C. WOOD* Brain Research Laboratory, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 43104 SUMMARY A decrement in the probability of eliciting a response is observed dur- ing the course of repetitive stimulation in many response systems of both metazoa and protozoa. Those forms of metazoan response decre- ment called habituation have recently been characterized behaviorally. In the studies reported here, the response decrement of the contractile protozoan, Stentor coeruleus, to repeated mechanical stimulation was systemically characterized to provide a comparison with metazoan habit- uation. This change in response probability was closely approximated by a negative exponential function after the first few stimuli. Animals responded to parametric variations of stimulus amplitude, interstimulus interval and retention period in a manner paralleling that observed in metazoa. However, neither interpolated large amplitude mechanical stimuli nor suprathreshold electrical stimuli produced dishabituation in Stentor though these stimuli are among the most effective dishabituating stimuli for metazoan tactile response systems. Behavioral analysis of the response decrement proceeded on the assumption that Stentor con- tains receptor and effector mechanisms only. Since the response decre- ment was not correlated with a change in responsiveness to electrical stimuli, the ability of the animal to contract appears to be unaltered by the process producing the response decrement. On the other hand, weak mechanical prestimuli were found to increase the rate of the response decrement which suggests that a process of receptor adaption is opera- tive. -

Orienting Response Reinstatement and Dishabituation: the Effects of Substituting

Orienting Response Reinstatement and Dishabituation: The Effects of Substituting, Adding and Deleting Components of Nonsignificant Stimuli Gershon Ben-Shakar, Itamar Gati, Naomi Ben-Bassat, and Galit Sniper The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Acknowledgments: This research was supported by The Israel Science Foundation founded by The Academy for Sciences and Humanities. We thank Dana Ballas, Rotem Shelef, Limor Bar, and Erga Sinai for their help in the data collection. We also thank John Furedy and an anonymous reviewer for the helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. The article was written while the first author was on a sabbatical leave at Brandeis University. We wish to thank the Psychology Department at Brandeis University for the facilities and the help provided during this period. Address requests for reprints to: Prof. Gershon Ben-Shakhar Department of Psychology, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem, 91905, ISRAEL Running Title: OR Reinstatement and Dishabituation 2 ABSTRACT This study examined the prediction that stimulus novelty is negatively related to the measure of common features, shared by the stimulus input and representations of preceding events, and positively related to the measure of their distinctive features. This prediction was tested in two experiments, which used sequences of nonsignificant verbal and pictorial compound stimuli. A test stimulus (TS) was presented after 9 repetitions of a standard stimulus (SS), followed by 2 additional repetitions of SS. TS was created by either substituting 0, 1, or 2 stimulus components of SS (Experiment 1), or by either adding or deleting 0, 1, or 2 components of SS (Experiment 2). The dependent measure was the electrodermal component of the OR to both TS (OR reinstatement) and SS that immediately followed TS (dishabituation). -

Women and Shoes... Page 3

Brought to you by Publishers of The Your Valley Source & The Promised Land FREE TAKE ONE The Western Slope’s Guide to Entertainment, Arts & News for May 2012 Women and Shoes... Page 3 Catching up with Cody Gay Page 13 Desert Rocks Festival Page 9 GRAND JUNCTION Test Drive the All New 2012 Jeep Compass CHRYSLER • JEEP • DODGE 2578 HWY 6 & 50 Grand Junction (on the corner of motor & funny little street) 245-3100 • 1-800-645-5886 THE EVOLUTION OF A TRULY LEGENDARY BLOODLINE www.grandjunctionchrysler.com • Sales: Mon-Fri 8:30-6:00, Sat 8:30-5:00 • Parts and Service: Mon - Fri 7:30-5:30, Sat 9:00-1:00 / Closed on Sundays Largest Lighting Showroom in Western Colorado 10,000 sq ft of Lighting • Accessories The SOURCE Tiffany Lamps • Led Flowers • Fountains Over 100 manufacturers FREE Residential Lighting Design Certified Lighting Designers Save up to 50% New Construction & Contractor Discounts New Products Arrive Daily! Not Just a Lighting Showroom Mirrors • Candle Holders • Plate Racks • Lamps Lamp Shades • Clocks • Vases • Flowers • Pictures Tables • Chairs • Wine Racks Final Countdown Bonus rebates of up to an EXTRA WE ARE AN XCEL ENERGY ALLY PARTNER! 30% for T12 upgrades • Let One Source Lighting do all of the leg work from April 1 to December 31, 2012* to receive lighting rebates! 2 • Xcel Energy Will Pay Up To 50% of your project! We have the Only Lighting Efficiency Professional Certification in the Grand Junction Area. Don’t forget for all of your commercial lighting needs. Ask about our FREE Commercial Lighting Energy Audit. -

Infants' Visual Processing of Faces and Objects: Age-Related Changes In

Infants’ Visual Processing of Faces and Objects: Age-Related Changes in Interest, and Stability of Individual Differences Marybel Robledo ([email protected])1 Gedeon O. Deák ([email protected])1 Thorsten Kolling ([email protected])2 1Department of Cognitive Science, University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA 92093-0515 USA 2Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität, Institut für Psychologie D-60054 Frankfurt/Main Germany Abstract quickly infants process a stimulus. Also, dishabituation might relate to infants’ interest in novelty, which might Longitudinal measures of infant visual processing of faces and objects were collected from a sample of healthy infants reflect curiosity. These ideas are bolstered by findings that (N=40) every month from 6 to 9 months of age. Infants infant habituation predicts later cognitive skills. For performed two habituation tasks each month, one with novel example, Thomson, Faulkner, and Fagan (1991) found a female faces as stimuli, and another with novel complex correlation between infants’ novelty preference and Bayley objects. Different individual faces and objects served as Scales of Infant Development scores (BSID, a standardized habituation (i.e., visual learning) and dishabituation (i.e., test of cognitive, language, and social skills) at 12 and 24 novelty response) stimuli. Measures included overall looking time to the habituation stimuli, slope of habituation, and months of age. Also, a meta-analysis by McCall and recovery to the dishabituation stimuli. Infants were more Carriger (1993) showed a consistent relation between interested in faces than objects, but this was contextualized habituation in the first year and IQ from 1 to 8 years. -

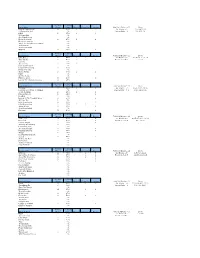

Up to Here # Times Played % Shows Played Opened Closed Set Encore

# Times % Shows Up To Here Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 11 Show Blow at High Dough 9 60% 2 3 Set Blocks = 6 1,5,7,9,12,14 I'll Believe In You 0% Encore Sets = 5 2,6,8,11,15 NOIS 10 67% 1 4 38 Years Old 0% She Didn't Know 0% Boots Or Hearts 10 67% 2 4 Everytime You Go 0% When The Weight Comes Down 0% Trickle Down 0% Another Midnight 0% Opiated 8 53% 1 2 # Times % Shows Road Apples Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 11 Show Little Bones 8 53% 1 1 Set Blocks = 8 1,2,4,6,8,10,12,15 Twist My Arm 8 53% 1 2 1 Encore Sets = 3 3,9,13 Cordelia 0% The Luxury 5 33% 1 Born In The Water 0% Long Time Running 4 27% Bring It All Back 0% Three Pistols 6 40% 1 1 Fight 0% On The Verge 0% Fiddler's Green 6 40% 3 Last Of The Unplucked Gems 4 27% # Times % Shows Fully Completely Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 13 Show Courage 10 67% 2 4 Set Blocks = 7 3,5,8,10,11,13,15 Looking For A Place To Happen 0% Encore Sets = 6.1 1,2,4,7,9,14,15 100th Meridian 10 67% 2 3 Pigeon Camera 2 13% 1 Lionized 0% Locked In The Trunk Of A Car 3 20% 2 We'll Go Too 1 7% Fully Completely 4 27% 3 Fifty Mission Cap 5 33% 1 1 Wheat Kings 8 53% 4 The Wherewithal 0% Eldorado 3 20% 1 # Times % Shows Day For Night Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 13 Show Grace, Too 13 87% 1 4 Set Blocks = 9 2,3,5,6,7,9,11,13,14 Daredevil 7 47% 1 Encore Sets = 4 4,10,12,15 Greasy Jungle 5 33% 1 Yawning Or Snarling 2 13% Fire In The Hole 0% So Hard Done By 7 47% 1 Nautical Disaster 4 27% 2 Thugs 2 13% Inevitability Of Death 0% Scared 7 47% 2 An Inch An Hour 0% Emergency 0% Titanic Terrarium 0% Impossibilium 0% # Times % Shows Trouble At The Henhouse Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 13 Show Giftshop 11 73% 1 5 Set Blocks = 6 3,5,7,10,12,14 Springtime In Vienna 7 47% 1 1 Encore Sets = 7 1,4,6,8,11,13,15 Ahead By A Century 13 87% 2 7 Don't Wake Daddy 4 27% 1 Flamenco 5 33% 2 700 Ft. -

Timing of the Acoustic Startle Response in Mice: Habituation and Dishabituation As a Function of the Interstimulus Interval

International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 2001, 14, 258-268. Copyright 2001 by the International Society for Comparative Psychology Timing of the Acoustic Startle Response in Mice: Habituation and Dishabituation as a Function of the Interstimulus Interval Aya Sasaki, William C. Wetsel, Ramona M. Rodriguiz, and Warren H. Meck Duke University, U.S.A. The hypothesis that the standard acoustic startle response (ASR) paradigm contains the elements of interval timing was tested. Acoustic startle stimuli were presented at a 10-s interstimulus interval (ISI) for 100 trials leading to habituation of the ASR. The ISI was then changed to either a shorter (5-s) or a longer (15-s) duration using a between- subjects design. Dishabituation of the ASR was used to measure the degree of temporal generalization for the interval-timing process. The ASR showed dishabituation at both shorter and longer ISI values on the first trial following the change in ISI. The dis- habituation resulting from the change in ISI was temporary and the ASR rapidly re- turned to levels of response habituation showing rate sensitivity to the frequency of stimulus presentation. Interval timing may be a standard feature of this habituation paradigm, it serves to anticipate the time of occurrence of the subsequent stimulus and to prepare the startle response, and provides a computational dimension lacking in the habituation process per se. The acoustic startle response (ASR) is a protective behavioral reaction con- sisting of muscle contractions of the eyelid, the neck, and the extremities that is elic- ited by sudden, loud acoustic stimuli. The ASR has been shown to be mediated by a simple subcortical pathway located in the ponto-medullary brainstem that consists of three synaptic stations in the central nervous system (e.g., Davis et al., 1982; Li et al., 2001). -

How Memory of the Past, a Predictable Present and Expectations of the Future Underpin Adaptation to the Sound Environment

STUDIES IN THE RESEARCH PROFILE BUILT ENVIRONMENT DOCTORAL THESIS NO. 1 How memory of the past, a predictable present and expectations of the future underpin adaptation to the sound environment Anatole Nöstl FACULTY OF ENGINEERING AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Department of Building, Energy and Environmental Engineering STUDIES IN THE RESEARCH PROFILE BUILT ENVIRONMENT DOCTORAL THESIS NO. 1 How memory of the past, a predictable present and expectations of the future underpin adaptation to the sound environment Anatole Nöstl © Anatole Nöstl 2015 Gävle University Press ISBN 978-91-88145-00-0 ISBN 978-91-88145-01-7 (pdf) urn:nbn:se:hig:diva-20082 Distribution: University of Gävle Faculty of Engineering and Sustainable Development SE-801 76 Gävle, Sweden +46 26 64 85 00 www.hig.se Print: Ineko AB, Kållered 2015 Abstract By using auditory distraction as a tool, the main focus of the present thesis is to investigate the role of memory systems in human adaptation processes towards changes in the built environment. Report I and Report II focus on the question of whether memory for regularities in the auditory environment is used to form predictions and expectations of future sound events, and if violations of these expectations capture attention. Collectively the results indicate that once a stable neural model of the sound environment is created, violations of the formed expectations can capture attention. Furthermore, the magnitude of attentional capture is a function of the pitch difference between the expected tone and the presented tone. The second part of the thesis is concerned with, (a) the nature (i.e. the specificity) of the neural model formed in an auditory environment and, (b) whether complex cognition in terms of working memory capacity modulates habituation rate. -

Rosario Dawson Ralph Fiennes

november 2005 | volume 6 | number 11 DVD SPOTLIGHT THE POLAR EXPRESS ROSARIO PAGE 56 DAWSON Rentearns RALPH FIENNES Voldemorttalks gift guide PAGE 24 PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40708019 PLUS ELLEN BARKIN, SUSAN SARANDON AND OTHER STARS ON THE PROS AND CONS OF BOTOX 200494Grey 4/18/05 11:00 PM Page 1 16.25" 15.25" 14" ©2005 P&G ® ® 10" 10.5" 11.375" expressions™ how can you hold on to perfectly beautiful colour? Make it look perfectly healthy with Pantene Pro-V Expressions for Reds, Blondes and Brunettes. Specialized pro-vitamin formulas make your unique shade look richer longer, alive with shine and dimension.* When your hair looks perfectly healthy, your colour is perfectly beautiful. Complete shade collections with shampoos, conditioners and more. Shampoo+conditioner vs Pantene shampoo alone pantene.com/expressions * THIS ADVERTISEMENT PREPARED BY GREY WORLDWIDE STUDIO777 777 THIRD AVENUE NEW YORK, NY 10017 CLIENT: P&G SIZE, SPACE: SPR 4C Bleed JOB #: 310-PE-069 PROOF: 2 PRODUCT: PANTENE Canada PUBS: Varius/consumer JOB#: 310-PE-069 ISSUE: 7/2005 CLIENT: P&G Pantene OP: IH collected 4/15/05 ART DIRECTOR: E. Horvath COPYWRITER: C. Ewing SPACE/SIZE: b: 16.25" x 11.375" t: 15.25" x 10.5" s: 14" x 10" FONTS: LOCATION: LEGAL RELEASE STATUS AD APPROVAL Release has been obtained Date: Acct Mgmt: Legal Coord: Art Director: Print Prod: 200494 Copywriter: Proofreader: GREY WORLDWIDE Creo on FG B.I. Studio: 200494Grey 4/18/05 11:00 PM Page 1 16.25" 15.25" 14" ©2005 P&G ® ® 10" 10.5" 11.375" expressions™ how can you hold on to perfectly beautiful colour? Make it look perfectly healthy with Pantene Pro-V Expressions for Reds, Blondes and Brunettes. -

Habituation and Dishabituation of Rats’

Animal Learning& Behavior 1979, 7 (4),525-536 Habituation and dishabituation of rats' exploration of a novel environment WILLIAM S. TERRY University ofNorth Carolina at Charlotte, Charlotte, North Carolina 28223 The habituation of locomotor activity across repeated exposures to a novel maze was studied in a series of experiments using rats as subjects. Habituation, defined as a decrease in ambula tion, was greater on a second trial occurring 5 min after a first trial than on one occurring 60 min after. This short-term decrement occurred only when the same maze was used on both trials, and could be dishabituated by intertrial detention in another novel environment. On a delayed test trial, habituation was, in one case, somewhat greater following initial spaced trials, and in another condition, comparable following both massed and spaced trials. The longer term habituation was maze specific, but was not affected by the presence of a dishabituator following either or both of the first two trials. The results were discussed in terms of theories of "priming" and encoding variability. Much of the recent interest in the response decre already active, or was "primed," in STM. Two ment that occurs with repeated exposures to a stim methods are suggested by which a stimulus could be ulus (i.e., habituation) has focused on the short-term primed. "Self-generated" priming occurs through effects of prior stimulation. For example, Davis the persisting trace in STM of a prior presentation of (1970) found more habituation of the startle response that same stimulus. This form of priming would of rats during a sequence of massed tone presenta especially characterize the short-term response decre tions than during spaced presentations. -

The Neuropsychology of Sigmund Freud

Reprinted from EXPERIMENTAL FOUNDATIONS OF CLINI CAL PSYCHOLOGY, edited by Arthur J. Bachrach. Copyright 1962 by Basic Books Publishing Co., Inc. 13 The Neuropsychology of Sigmund Freud KARL H. PRIBRAM The experimental foundations of clinical psychology deal, for the most part, with investigations of psychopathology. There is found another, somewhat less prevalent theme, however, characterized by an em phasis on basic, theory-directed questions. Clinical material is used as a caricature of the theoretical problem, and the hope is that better theory will be attained when the clinical phenomenon is related to laboratory experience. There is one branch of clinical endeavor that consistently uses this method: clinical neurology. <) Pathological ma terial is used to gain a better understanding not only of the abnormali ties in question but also of the fundamental workings of the brain and its regulation of behavior. John Hughlings Jackson, Henry Head, Otto Foerster, Harvey Cushing, Percival Bailey, Wilder Penfield, D. Denny Brown and F. M. R. Walshe are only a few names that attest to this tradition. Much of clinical psychology today either takes for granted or makes actual investigations of notions which can be directly traced back to Sigmund Freud. Many of the chapters in this book detail experimental o As I indicated in a recent paper on the interrelations between psychology and the neurological sciences (1962), clinical neurology is, to a large extent, a neuropsychological discipline; namely, the investigation of neurological proc esses-normal and pathological-by behavioral techniques. Perhaps partly be cause of the poor prognosis attached to diseases of the central nervous system, and partly because of the difficulties in the mastery of neurological knowledge in the first place, clinical neurologists have invariably used clinical material to pose basic, i.e., theory-directed questions.