A Brief Guide to Monitoring Anti- Trans Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trans Activism

DECEMBER 2020 Trans Activism BILL C-16 & THE TRANS MARCH Prepared by Approved by DOROTHY THOMPSON, JONATHAN STEWART, DIRECTOR SOCIAL MEDIA SOCIAL MEDIA EXECUTIVE Please follow the steps to complete the zone: 1) Watch the video 2) Read through the booklet contents 3) Answer the discussion questions as a group Content warning Police violence, nudity, swearing, transphobia, homophobia Bill C-16 On June 17th in 2017, Bill C-16 was passed in Parliament. The Bill amended the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code to provide protection to individuals from discrimination on the basis of gender identity and gender expression. After the Bill passed, any What is a bill? actions motivated by hate, bias, or discrimination If someone wants to regarding someone's create a new law, gender expression or they first present it as a "bill." The bill must identity became illegal and be approved by could be used to determine several levels of a criminal sentence. government and signed by the Prime Individuals who are Minister before it protected under the becomes a law. Human Rights Act are people who may otherwise have unequal opportunity to live in society and have their needs accommodated without discrimination. Page 1 Meet a local activist Charlie Lowthian-Rickert, a young activist from Ottawa, spoke out in support of passing Bill C-16. When speaking to politicians and fellow activists before the Bill was passed, she said: "It could protect us and stop the people who would have just gone off and done it in the past, and discriminated or assaulted us. -

The Transgender-Industrial Complex

The Transgender-Industrial Complex THE TRANSGENDER– INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX Scott Howard Antelope Hill Publishing Copyright © 2020 Scott Howard First printing 2020. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied, besides select portions for quotation, without the consent of its author. Cover art by sswifty Edited by Margaret Bauer The author can be contacted at [email protected] Twitter: @HottScottHoward The publisher can be contacted at Antelopehillpublishing.com Paperback ISBN: 978-1-953730-41-1 ebook ISBN: 978-1-953730-42-8 “It’s the rush that the cockroaches get at the end of the world.” -Every Time I Die, “Ebolarama” Contents Introduction 1. All My Friends Are Going Trans 2. The Gaslight Anthem 3. Sex (Education) as a Weapon 4. Drag Me to Hell 5. The She-Male Gaze 6. What’s Love Got to Do With It? 7. Climate of Queer 8. Transforming Our World 9. Case Studies: Ireland and South Africa 10. Networks and Frameworks 11. Boas Constrictor 12. The Emperor’s New Penis 13. TERF Wars 14. Case Study: Cruel Britannia 15. Men Are From Mars, Women Have a Penis 16. Transgender, Inc. 17. Gross Domestic Products 18. Trans America: World Police 19. 50 Shades of Gay, Starring the United Nations Conclusion Appendix A Appendix B Appendix C Introduction “Men who get their periods are men. Men who get pregnant and give birth are men.” The official American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) Twitter account November 19th, 2019 At this point, it is safe to say that we are through the looking glass. The volume at which all things “trans” -

Grassroots Event Focuses on Black, Brown Trans

Photo by Tim Peacock VOL 35, NO. 21 JULY 8, 2020 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com E. PATRICK JOHNSON A profile of the newest NU dean. Photo from Johnson's website, run with permission 10 DAVID ZAK Leaves Pride Films and Plays amid controversy. Photo by Bob Eddy MARCH 13 POLITICAL PARTY FORWARD Durbin, Baldwin meet with Grassroots event focuses supporters. Official photo of U.S. Sen. Tammy Baldwin on Black, Brown trans lives 5 PAGE 4 @windycitytimes /windycitymediagroup @windycitytimes www.windycitymediagroup.com July 8, 2020 WINDY CITY TIMES PAGE 6 Chicago Pride Parade 2019. Photo by Kat Fitzgerald (www.MysticImagesPhotography.com) "Kickoff," The Chicago Gay Pride Parade 1976. Diane Alexander White Photography TWO SIDES OF PAGE 20 YESTERDAY APRIL 29, 2020 VOL 35, NO. 20 Looking back at Pride memories of the past (above) WINDYJUNE 24, 2020 and this month’s Drag March for Change (below) PRIDEChicagoBuffalo Pridedrives Grove postponed; on Pride VOL 35, NO. 16 CITY www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com AND TODAY EDDIE TIMES HUNSPERGER PAGE 17 Activist and partner of Rick Garcia dies. Photo of Hunsperger (right) and Garcia courtesy of Garcia 4 Buffalo Grove Pride 2019. SEEING Tim Carroll Photography THE LIGHT Lighthouse Foundation prepares programming. Photo of Rev. Jamie Frazier by Marcel Brunious 8 PAGE 4 www.windycitymediagroup.com From the Drag March for Change. Photo by Vernon Hester @windycitytimes /windycitymediagroup @windycitytimes www.windycitymediagroup.com @windycitytimes FUN AND GUNN Tim Gunn on his new show, /windycitymediagroup 'Making the Cut'. Photo by Scott McDermott 13 @windycitytimes SUPPORT Photo by Tim Peacock 2 VOL 35, NO. 21 JULY 8, 2020 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com E. -

Selfless Career & Commitment to Lgbt Cause

Year 4, Vol. 11 • November 3, 2011 - November 30, 2011 • www.therainbowtimesnews.com FREE! The H CULTICE P PHOTO: JOSE RThe Freshestainbow Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender T Newspaperimes in New England JOSHUA INGRAHAM SHOWS YOU PHOTO: GUSTAVO MONROY PHOTO: GUSTAVO HOW… p10 TRT HERO: Boston’s Jim MORGRAGE RIDES PHOTO: JIM MORGRAGE TO FIGHT HIV/AIDS p13 THE 99-PERCENTERS OF OCCUPY BOSTON p20 PHOTO: GUNNER SCOTT LAUPEr’sSelfless Career & Commitment to LGBT Cause p8 Art Beat: A Success for AIDS Care Ocean State p20 Meet the final TRT Heroes: Jenn Tracz Grace & Gunner Scott p10 & 12 Massachusetts is ahead of the curve in HIV infection-rate reductions p5 2 • November 3, 2011 - November 30, 2011 • The Rainbow Times • www.therainbowtimesnews.com And the Award(s) go to… The Occupy movement could grow even TRT Endorsements By: Jenn Tracz Grace*/CABO’s Executive Director n October 18th stronger by joining other local activist groups for Massachusetts CABO held its 4th By: Jason Lydon/TRT Columnist something is hap- Oanniversary cel- ike Konczal, a fellow with the Roos- pening and people Mayoral Candidates ebration, business expo evelt Institute who focuses on financial who weren’t paying and awards event. First, we reform, structural unemployment, con- attention before are By: Nicole Lashomb/TRT Editor-in-Chief M thank everyone who joined sumer access to financial services, and inequality beginning to pay at- n a matter of a few days, the munici- us. We had a great turnout recently wrote, “As people think a bit more criti- tention now. pal elections will take place in Mas- and for the 4th year in a row cally about what it means to ‘occupy’ contested Those of us on the Isachusetts. -

Degenderettes Protest Artwork Exhibiton Label Text

Degenderettes Antifa Art Exhibition Label Text Degenderettes Protest Artwork “Tolerance is not a moral absolute; it is a peace treaty.” Yonatan Zunger wrote these words in the weeks leading up to the first Women’s March in 2017. In the same article he suggested that the limits of tolerance could best be illustrated by a Degenderette standing defiantly and without aggression, pride bat in hand. Throughout this exhibit you will see artifacts of that defiance, some more visceral or confrontational than others, but all with the same message. Transgender people exist and we are a part of society’s peace treaty—but we are also counting the bodies (at least seven transgender people have been killed in the United States since the beginning of 2018). We Degenderettes are present at shows of solidarity such as the Trans March, Dyke March, Women’s March, and Pride. We endeavor to provide protection for transgender people at rallies and marches in San Francisco, Oakland, and Berkeley. We show up in opposition to people who seek to harm the transgender community—people like Milo Yiannopoulos, whose track record of outing transgender students and doxing immigrants inspired a contingent of Degenderettes to protest his fateful visit to U.C. Berkeley in February 2017. It was in the wake of the confrontation at U.C. Berkeley that shields were identified as weapons by the Berkeley Police Department and banned from all subsequent protests in the city. These guidelines have been adopted throughout the rest of the Bay Area. To us, the shields and everything else in this exhibit are still a type of armor. -

Seafijters LOG APRIL 18

APRIL 18 SEAFijtERS LOG 1952 • OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE S E A F A R E R S I N TE R N AT I O N A L UNION • ATLANTIC AND GULF DISTRICT • AFL • sn; LAYUPS RISE .Ua " • story on Page 3 U5PH5 Curbs 'CaseChasers' Story on Page 2 1: ,V! Jtfisaur Shown being nudged back to the yard in Chester, Pa., for finishing now 8/uCCn* touches and installation of machinery, the Keystone Mariner, launched in February, is expected to be ready for service in June. First of 35 planned Marinertype ships, the speedy vessel will probably be crewed by Seafarers for an SIU contraCted company when she makes her maiden run. (Story on Page 2.) e!!9S?? Pac* Tw« SEAFARERS LOG PrMiOr. ASrfl It. ItSS Union Endorses First Wheat to Transjordan Half Million Paid Out In USPHS Crackdown Vac. Money 'Rounding out the first two months of operation the SIU Va cation Plan has already paid out On Case^Chasers well over a half million dollars to A crackdown on ambulance chasers has been instituted by seamen sailing SIU ships. With the first crush of applications over, the Staten Island USPHS Hospital. From now on, the the Vacatio.n Office at headquar hospital will take legal action against any lawyer found ters has itself been able to take a soliciting cases among seamen ' bit of a breathing spell. who are patients at the hos a seaman who has suffered a ship Reliable estimates hint that the pital. board injury and persuade him to original $2.5 million expected to Dr. -

Of the Human Rights Situation of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex People in Europe and Central Asia

OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION OF LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, TRANS AND INTERSEX PEOPLE IN EUROPE AND CENTRAL ASIA FIND THIS REPORT ONLINE: WWW.ILGA-EUROPE.ORG THIS REVIEW COVERS THE PERIOD OF JANUARY TO DECEMBER 2019. Rue du Trône/Troonstraat 60 Brussels B-1050 Belgium Tel.: +32 2 609 54 10 Fax: + 32 2 609 54 19 [email protected] www.ilga-europe.org Design & layout: Maque Studio, www.maque.it ISBN 978-92-95066-11-3 FIND THIS REPORT ONLINE: WWW.ILGA-EUROPE.ORG Co-funded by the Rights Equality and Citizenship (REC) programme 2014-2020 of the European Union This publication has been produced with the financial support of the Rights Equality and Citizenship (REC) programme 2014-2020 of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of ILGA-Europe and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Commission. ANNUAL REVIEW OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION OF LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, TRANS, AND INTERSEX PEOPLE COVERING THE PERIOD OF JANUARY TO DECEMBER 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS KAZAKHSTAN INTRODUCTION KOSOVO* A NOTE ON DATA COLLECTION AND PRESENTATION KYRGYZSTAN HIGHLIGHTS, KEY DEVELOPMENTS AND TRENDS LATVIA INSTITUTIONAL REVIEWS LIECHTENSTEIN LITHUANIA EUROPEAN UNION LUXEMBOURG UNITED NATIONS MALTA COUNCIL OF EUROPE MOLDOVA ORGANISATION FOR SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE MONACO MONTENEGRO COUNTRY REVIEWS NETHERLANDS ALBANIA NORTH MACEDONIA ANDORRA NORWAY A ARMENIA POLAND AUSTRIA PORTUGAL AZERBAIJAN ROMANIA BELARUS RUSSIA BELGIUM SAN MARINO BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA SERBIA BULGARIA SLOVAKIA -

San Francisco Pride Announces Additional Entertainment and Special Guests for Official Pride 50 Online Celebration

Media Contacts: Julie Richter | [email protected] Peter Lawrence Kane | [email protected] SAN FRANCISCO PRIDE ANNOUNCES ADDITIONAL ENTERTAINMENT AND SPECIAL GUESTS FOR OFFICIAL PRIDE 50 ONLINE CELEBRATION JUNE 27–28, 2020 SAN FRANCISCO (June 18, 2020) — Today, the Board of Directors of San Francisco Pride announced additional entertainment and special Guests participatinG in the official Pride 50 online celebration takinG place Saturday, June 27 and Sunday, June 28, 2020. To celebrate the milestone anniversary, San Francisco leGendary draG icons Heklina, Honey Mahogany, Landa Lakes, Madd Dogg 20/20, Peaches Christ, and Sister Roma will come toGether for Decades of Drag, a conversation where they reflect on decades of activism, struGGles, and victories. JoininG the previously announced artists, the tribute to LGBTQ+ luminaries and Queer solidarity includes performances by Madame Gandhi, VINCINT, Elena Rose, Krystle Warren, La Doña, and LadyRyan, presented by SF Queer NiGhtlife. The weekend proGram also features a spotliGht on Openhouse and the livinG leGacy of Black Queer and transgender activism; National Center for Lesbian RiGhts Exeutive Director Imani Rupert-Gordon discussinG Black Lives Justice; and a deep dive into the history of the LGBTQ+ community in music with Kim Petras. Additional special appearances include Bay Area American Indian TwoSpirits, body positive warrior Harnaam Kaur, AlPhabet Rockers, Cheer SF (celebratinG forty years!), a conversation on the intersection of Black and Gay issues between Dear White People creator Justin Simien and cast member Griffin Matthews, and best-of performances from San Francisco’s oldest Queer bar The Stud. Previously announced entertainment includes hosts Honey Mahogany, Per Sia, Sister Roma, and Yves Saint Croissant, as well as New Orleans-born Queen of Bounce, Big Freedia as the Saturday headliner. -

Transgender History / by Susan Stryker

u.s. $12.95 gay/Lesbian studies Craving a smart and Comprehensive approaCh to transgender history historiCaL and Current topiCs in feminism? SEAL Studies Seal Studies helps you hone your analytical skills, susan stryker get informed, and have fun while you’re at it! transgender history HERE’S WHAT YOU’LL GET: • COVERAGE OF THE TOPIC IN ENGAGING AND AccESSIBLE LANGUAGE • PhOTOS, ILLUSTRATIONS, AND SIDEBARS • READERS’ gUIDES THAT PROMOTE CRITICAL ANALYSIS • EXTENSIVE BIBLIOGRAPHIES TO POINT YOU TO ADDITIONAL RESOURCES Transgender History covers American transgender history from the mid-twentieth century to today. From the transsexual and transvestite communities in the years following World War II to trans radicalism and social change in the ’60s and ’70s to the gender issues witnessed throughout the ’90s and ’00s, this introductory text will give you a foundation for understanding the developments, changes, strides, and setbacks of trans studies and the trans community in the United States. “A lively introduction to transgender history and activism in the U.S. Highly readable and highly recommended.” SUSAN —joanne meyerowitz, professor of history and american studies, yale University, and author of How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality In The United States “A powerful combination of lucid prose and theoretical sophistication . Readers STRYKER who have no or little knowledge of transgender issues will come away with the foundation they need, while those already in the field will find much to think about.” —paisley cUrrah, political -

Varje Dag Utmanar Jag Någons Föreställning Om

SVERIGES FÖRENADEa HBTQ-STUDENTERnn PRESENTERAR:abe W NR 16 TEMA: FÖRÄNDRING VARJE DAG UTMANAR JAG NÅGONS FÖRESTÄLLNING OM KÖN QUEER IT UP, EUROPE! • COMBATING HOMOPHOBIA AT SCHOOL VIKINGATIDENS TRANSPERSONER? • ÖPPENHET PÅ 2000-TALET Wannabe nr 16 Förändring på gång… Nu är Wannabe här igen! innehåll Förbundsordföranden har ordet CAMILLA NYLUNDH s. 4 Tiderna förändras. Sedan Wannabe nr 15 har Förändring är också ett ord som används allt SFQ fått en ny styrelse och Wannabe har fått flitigare i samhället då alla uppmanas till ständig Presentation av förbundsstyrelsen s. 6 ytterligare en chefredaktör. SFQ:s före detta vice personlig förändring – en uppmaning som inte tar Queer It Up, Europe! MONIKA GRZYWNOWICZ s. 8 förbundsordförande Sara Nilsson har tagit plats som hänsyn till att förutsättningarna för förändring är Combating homophobia at school MARZANNA POGORZELSKA s. 10 chefredaktörspartner till Anna Olovsdotter Lööv. ojämlikt fördelade, och den som inte lyckas förändra Om ett par veckor kommer det att bli möjligt för sitt liv får själv bära skulden för det. Då tiden gör Varje dag utmanar jag någons föreställning om kön HANNA ANDERBERG s. 14 samkönade par att gifta sig i Sverige. Samtidigt att allting ständigt förändras, men kanske inte alltid Rapport från SFQ:s lokalavdelningskonferens CAMILLA ALEXANDERSSON, KARIN MELIN s. 18 så verkar förändring aldrig komma till stånd inom i den riktning man skulle kunna önska, vill vi i det Älskling ULLIS CARLSSON s. 20 vissa områden. Steriliseringskravet för transsexuella här numret av Wannabe lyfta fram människor som Vikingatidens transpersoner? LISA OLOFSSON s. 22 kvarstår fortfarande trots stora protester och vi dagligen kämpar för förändring i riktningen mot har fortfarande en socialminister som ”tycker” att en bättre värld för hbtq-personer. -

June 15 Issue

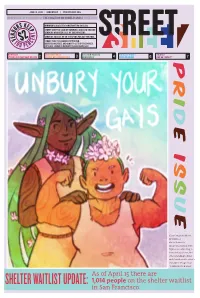

JUNE 15, 2018 | BIMONTHLY | STREETSHEET.ORG INDEPENDENTLY PUBLISHED BY THE COALITION ON HOMELESSNESS SINCE 1989 MINIMUM SUGGESTED DONATION TWO DOLLARS. STREET SHEET IS SOLD BY HOMELESS AND LOW-INCOME VENDORS WHO KEEP 100% OF THE PROCEEDS. VENDORS RECEIVE UP TO 75 PAPERS PER DAY FOR FREE. STREET SHEET IS READER SUPPORTED, ADVERTISING FREE, AND AIMS TO LIFT UP THE VOICES OF THOSE LIVING IN POVERTY IN SAN FRANCISCO. NEWFLASH BART HAS FAILED ELECTION RESULTS POLICE AT PRIDE TREATED STORIES YOU MAY HAVE MISSED 2 PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES 3 AN ANALYSIS 4 ARE A PROBLEM 6 LIKE AN “ADDICT” 7 P R I D E I S S U E Cover image by Oliver Northwood @allofthenorth image description: Two figures, one standing in front flexing biceps, the other standing behind with hands on the other’s shoulders. Image reads “UNBURY YOUR GAYS” As of April 15 there are SHELTER WAITLIST UPDATE: 1,014 people on the shelter waitlist in San Francisco. JUNE 15, 2018 PAGE 2 ASK US COALITION ON HOMELESSNESS NEWSFLASH ANYTHING HOMELESSNESS HEADLINES YOU MAY HAVE MISSED HAVE A QUESTION YOU WANT US TO AN- AmAzon Flexes muscles, seAttle BAcks Down on Business tAx The STREET SHEET is a project of the (New York Times) SWER ABOUT HOMELESSNESS OR HOUSING Coalition on Homelessness. The Coalition on Homelessness organizes poor and IN THE BAY AREA? ASK US AT homeless people to create permanent The city of Seattle, after resistance from Amazon and other compa- solutions to poverty while protecting the nies, will end a tax on companies making at least $20 million. -

SAN FRANCISCO PRIDE ANNOUNCES 2019 COMMUNITY GRAND MARSHALS and HONOREES Five Community Grand Marshals and Eight Awardees to Be Honored at the 49Th Annual Event

SAN FRANCISCO LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, TRANSGENDER PRIDE PARADE AND CELEBRATION COMMITTEE, INC. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 15, 2019 CONTACT: [email protected] | (415) 508-5538 SAN FRANCISCO PRIDE ANNOUNCES 2019 COMMUNITY GRAND MARSHALS AND HONOREES Five Community Grand Marshals and Eight Awardees to be honored at the 49th Annual Event San Francisco, CA – The 49th Annual San Francisco LGBT Pride Celebration and Parade will be held on June 29 and 30, 2019. The Parade/March is Sunday, June 30 in the heart of downtown San Francisco beginning at 10:30 AM. A two-day Celebration and Rally is scheduled from Noon to 6:00 PM on Saturday, June 29, and from 11:00 AM to 6:00 PM on Sunday, June 30 at San Francisco’s Civic Center Plaza and surrounding neighborhood. “2019 is a momentous year in the history of our movement. With almost one million people gathering in San Francisco, we will join the world in commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall Riots in New York City,” said SF Pride Executive Director, George Ridgely, Jr. “This year’s theme, Generations of Resistance, is not only a nod to the heroes of Stonewall, but also to those at Compton’s Cafeteria who stood up against police brutality in 1966, and the decades of LGBTQ+ activism, creativity, and advocacy born right here in San Francisco. Each of our honorees exemplify the tenacity and compassion that underscore a resistance that results in positive change. Our strength as a community is tied inextricably with visibility, and we are honored to showcase the accomplishments of these excellent individuals and organizations.