Discussion Paper V7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Rivers Social Profile

Northern Rivers Social Profile PROJECT PARTNER Level 3 Rous Water Building 218 Molesworth St PO Box 146 LISMORE NSW 2480 tel: 02 6622 4011 fax: 02 6621 4609 email: [email protected] web: www.rdanorthernrivers.org.au Chief Executive Officer: Katrina Luckie This paper was prepared by Jamie Seaton, Geof Webb and Katrina Luckie of RDA – Northern Rivers with input and support from staff of RDA-NR and the Northern Rivers Social Development Council, particularly Trish Evans and Meaghan Vosz. RDA-NR acknowledges and appreciates the efforts made by stakeholders across our region to contribute to the development of the Social Profile. Cover photo Liina Flynn © NRSDC 2013 We respectfully acknowledge the Aboriginal peoples of the Northern Rivers – including the peoples of the Bundjalung, Yaegl and Gumbainggirr nations – as the traditional custodians and guardians of these lands and waters now known as the Northern Rivers and we pay our respects to their Elders past and present. Disclaimer This material is made available by RDA – Northern Rivers on the understanding that users exercise their own skill and care with respect to its use. Any representation, statement, opinion or advice expressed or implied in this publication is made in good faith. RDA – Northern Rivers is not liable to any person or entity taking or not taking action in respect of any representation, statement, opinion or advice referred to above. This report was produced by RDA – Northern Rivers and does not necessarily represent the views of the Australian or New South Wales Governments, their officers, employees or agents. Regional Development Australia Committees are: Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. -

Weekly Markets Continued Byron Bay Artisan Market Caldera Farmers

Weekly Markets Weekly Markets continued 1st Weekend of the Month Continued Lismore Produce Market Byron Bay Artisan Market Make It Bake It Grow It Market Magellan St (between Carrington & Molesworth St, Lismore CBD) Railway Park, Johnson St Byron Bay Summerland House Farm, 253 Wardell Road, Alstonville 02 6622 5141 02 6685 6807 (Tess Cullen) 0417 547 555 Every Thursday 3.30pm - 7pm w: byronmarkets.com.au/artisan.html w:makeitbakeitgrowit.com.au from October - Easter only, Saturdays 4pm - 9pm 1st Sunday 9am - 1pm Lismore Organic Market Lismore Showground, Caldera Farmers Market Kyogle Bazaar 02 6636 4307 Murwillumbah Showground Kyogle CBD w: tropo.org.au 02 6684 7834 0416 956 744 Every Tuesday 7.30am - 11am w: calderafarmersmarket.com.au 1st & 3rd Saturdays 8am - 4pm Every Wednesday 7am - 11am Lismore Farmers Market 2nd Weekend of the Month Lismore Showground, Nth Lismore Mullumbimby Farmers Market The Channon Craft Market 02 6621 3460 Mullumbimby Showground, 51 Main Arm Rd, Mullumbimby Coronation Park, The Channon Every Saturday 8am - 11am 02 6684 5390 02 6688 6433 w: mullumfarmersmarket.org.au w: thechannonmarket.org.au Nimbin Farmers Market Every Friday 7am - 11am e: [email protected] Next to The Green Bank, Cullen St, Nimbin 2nd Sunday 9am - 3pm 02 6689 1512 (Jason) Uki Produce Market Every Wednesday 3pm - 6pm Uki Hall, Uki Alstonville Market 02 6679 5438 Apex Pavilion, Alstonville Showground (undercover) Alstonville Farmers Market Every Saturday 8am - 12pm 02 6628 1568 Bugden Ln, opp Federal Hotel, behind Quattro, Alstonville -

Timely Care Provided

Northern exposure Newsletter, Issue 9 October 2013 More timely Care Provided The latest Bureau of Health Information (BHI) Quarterly Report “The high praise received from Patients for April-June 2013 has found that NNSW LHD Hospitals are generally providing more timely care. This is of great benefit to is a compliment to the dedication of our our Patients. Mental Health Staff.” Surgery and Emergency Targets met All 934 Category One elective surgical procedures were Of the Patients who responded to the Survey, 26% rated the completed within the 30 day timeframe. The Category Two service as excellent, 31% rated it as very good with only 6% rated (admit within 90 days) target is 93% and the LHD achieved a it as poor. The first two results are reported to be the highest very pleasing result of 97%, having performed 1,218 procedures in the State, while the poor rating was received from the least within the time-frame. For Category Three, the target is 95%, number of Patients, who completed this NSW Health Patient which is to admit with 365 days and the LHD completed 1,499 Survey. procedures with a result of 98%. Mental illness is a heavy burden for individuals and their families A total of 3,651 elective surgical procedures were undertaken and it can have far reaching consequences on society as a whole. across the NNSW LHD for this period. Lismore Base Hospital People with a mental illness suffer from a range of disorders (LBH) performed 1,189 procedures followed by The Tweed such as anxiety, depression and schizophrenia. -

Here for Acon Northern Rivers

HERE FOR ACON NORTHERN RIVERS This guide can be shared online and printed. To add or edit a listing please contact ACON Northern Rivers NORTHERN RIVERS LOCAL LGBTI SOCIAL AND SUPPORT GROUPS AllSorts LGBTIQ and Gender Tropical Fruits Inc. Trans and Gender Diverse Diverse Youth Group on the 6622 6440 | www.tropicalfruits.org.au Social Group, Lismore Tweed Facebook - The Tropical Fruits Inc Mal Ph: 0422 397 754 Tammie Ph: 07 5589 1800 | 0439 947 566. Social events and support for LGBTIQ and friends [email protected] Meets monthly for LGBTI & gender diverse A monthly casual get-together for transgender, young people aged16 to 24 years in the Tweed Queer Beers Brunswick Heads gender diverse, gender non-conforming or gender questioning people, sistergirls and Compass Tweed/Southern Facebook - queer-beers brotherboys Gold Coast LGBTIQAP+ Youth Mixed -Gender, monthly social in the beer garden at the Brunswick Heads Hotel Men’s Lounge, Lismore Network Queer Beers Lismore Russell Ph: 0481 117 121 Claire Ph: 07 5589 8700 [email protected] [email protected] Facebook - queerbeerslismore A group of gay and bisexual men who meet at Compass is a youth-driven network of Good company, food, drinks & beats on the the Tropical Fruit Bowl in South Lismore on the community members and service providers 4th Sunday of every month, 4-8pm for the second Friday of each month uniting to provide safety, support, acceptance LGBTIQ community at the Northern Rivers Hotel and celebration for LGBTIQAP+ young people North Lismore Gay Tennis in Mullumbimby in the Tweed Shire and Southern Gold Coast Lismore Lads Club Lunch Contact ACON Northern Rivers Fresh Fruits LGBTIQ 6622 1555 | [email protected] Facebook - lismorelad’sclub Social Group A long running social tennis group that meets A monthly social get together of gay guys Wednesday nights, 6pm at the Mullumbimby 6625 0200 living with or affected by HIV, and our friends Tennis Courts and supporters. -

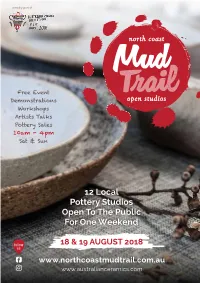

12 Local Pottery Studios Open to the Public for One Weekend

proudly part of Free Event Demonstrations Workshops Artists Talks Pottery Sales 10am - 4pm Sat & Sun 12 Local Pottery Studios Open To The Public For One Weekend follow 18 & 19 AUGUST 2018 us www.northcoastmudtrail.com.au www.australianceramics.com Sasa Scheiner August 2018 Sat 18 & Sun 19 10am to 4pm www.northcoastmudtrail.com.au Welcome! The Northern Rivers is a vibrant creative community that is fast becoming known as a major centre for Ceramic Arts. The region is a hub for traditional and contemporary ceramic artists and potters, some long standing locals, and a growing population of new talents. The diverse works crafted by these artisans are coveted by enthusiasts from all over the world, with pieces by many of the artists in galleries, retail outlets, restaurants, and private collections in America, Asia and Europe. Once a year, as part of The Australian Ceramics Association’s Open Studios, these artists open their spaces to the public for one weekend only, giving the opportunity for visitors to see demonstrations, hear artists’ talks, participate in workshops, learn about their processes, and purchase ceramics directly from the artists themselves. There will be thousands of beautiful pieces made with multiple methods and diverse finishes, as varied as the potters themselves. Whether you are looking for a fun piece of brightly coloured tableware, a decorative masterpiece, or a simple classic, perhaps a woodfired sculpture, or an alternatively fired gem, whatever your taste, there is a work of art perfect for everyone waiting to be discovered. Come along, have some fun, and pick up a piece of local treasure… North Coast Ceramics INC. -

RAIL TRAILS for NSW ABN 43 863 190 337 - a Not for Profit Charity

RAIL TRAILS FOR NSW ABN 43 863 190 337 - A Not for Profit Charity Chairman John Moore OAM RFD ED M. 0403 160 750 [email protected] Deputy Chairman Tim Coen B.Com. M. 0408 691 541 [email protected] Website: railtrailsnsw.com.au facebook: Facebook.com/railtrailsnsw NSW will generate up to $74 million every year create up to 290 jobs revitalise 90+ regional communities by building these tourism assets Submission for the 2020 NSW Budget Rail Trails for NSW August 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This submission champions 11 high quality tourist trail projects for regional NSW totalling 884 kilometres of safe, scenic, vehicle-free pathway on publicly owned, decades out of service, regional rail corridors. There are no prospects for re-activated train services along any of the nominated routes. Rail Trails for NSW urges the State Government to seek co-contributions from the Australian Government for the projects. The building of these tourist trails will provide: • Fiscal stimulus of up to $3.3 million for feasibility and other pre-construction studies and planning • Fiscal stimulus during the trail construction phase of up to $271,250,000 • Upon completion; o All 14 regional trails will generate additional local visitor spending estimated conservatively at $27 million p.a. building to $74 million p.a. o Steadily create up to 111 jobs building to 297 or more local jobs as visitor numbers grow o facilitate new business and employment opportunities in their host regions o provide community, health and exercise resources for locals o enable social benefits by generating community resilience, hope and optimism o stimulus of up to $2.75 million via marketing and promotion activities These 11 additional rail trails warranting immediate attention (Table 1). -

Sydney - Brisbane Land Transport

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Engineering and Information Faculty of Informatics - Papers (Archive) Sciences 1-1-2007 Sydney - Brisbane Land Transport Philip G. Laird University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers Part of the Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Laird, Philip G.: Sydney - Brisbane Land Transport 2007, 1-14. https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers/760 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Sydney - Brisbane Land Transport Abstract This paper shall commence with reference to the draft AusLink Sydney - Brisbane corridor strategy. Section 2 will outline the upgrading of the Pacific Highway, Section 3 will examine the existing Sydney - Brisbane railway whilst Section 4 will outline some 2009 - 2014 corridor upgrade options with particular attention to external costs and energy use as opposed to intercity supply chain costs. The conclusions are given in Section 5. The current population of the coastal regions of the Sydney - Brisbane corridor exceeds 8 million. As shown by Table I, the population is expected to be approaching 11 million by 2031. The draft strategy notes that Brisbane and South East Queensland will become Australia's second largest conurbation by 2026. Keywords land, transport, brisbane, sydney Disciplines Physical Sciences and Mathematics Publication Details Laird, P. G. (2007). Sydney - Brisbane Land Transport. Australasian Transport Research Forum (pp. 1-14). Online www.patrec.org - PATREC/ATRF. This conference paper is available at Research Online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers/760 Sydney - Brisbane land transport Sydney - Brisbane Land Transport Philip Laird University of Wollongong, NSW, Australia 1 Introduction This paper shall commence with reference to the draft AusLink Sydney - Brisbane corridor strategy. -

Mullumbimby - GP Synergy

6/29/2018 Mullumbimby - GP Synergy Home Calendar Image Gallery Contact Us Informatics | Login GPRime2 | Login TRAINING TRAINING TRAINING PUBLICATIONS PARTNER ABOUT US PROGRAMS OPPORTUNITIES REGIONS & NEWS EXPLORE GP WITH US You are here: Home / Town Proles / Mullumbimby Mullumbimby Mullumbimby is an alternative lifestyle centre in glorious surroundings. https://gpsynergy.com.au/townprofiles/mullumbimby/ 1/7 6/29/2018 Mullumbimby - GP Synergy Map data ©2018 Google Quick facts Training region North Eastern NSW Subregion North Coast GP Synergy grouping B RA/MMM classication RA2/MMM5 Population The population of Mullumbimby is more than 3,000 people, the median age is 44 years. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people make up 2% of the population. Mullumbimby is located within the North Coast Primary Health Network, these fact sheets provide an overview of the health needs of the North Coast community. Location Mullumbimby is a town in the Northern Rivers region of New South Wales and sits on the Brunswick River. It is located 23 minutes north west of Byron Bay, 50 minutes north east of Lismore and an 100 minutes south of Brisbane. Mullumbimby is a historic scenic country town and is known as the “Biggest Little Town in Australia” because of how much this https://gpsynergy.com.au/townprofiles/mullumbimby/ 2/7 6/29/2018 Mullumbimby - GP Synergy the Biggest Little Town in Australia because of how much this charming little town has to oer. Transport links The closest regional airport to Mullumbimby is Ballina/Byron Bay airport, which is a 32 minute drive from Mullumbimby. Regional Express Airlines (REX), Virgin Blue, and Jetstar oer return daily ights to Sydney and Fly Pelican Airlines oering daily return ights to Newcastle. -

Byron Shire Draft Residential Strategy

Byron Shire Draft Residential Strategy Public Exhibition version 2019 Acknowledgement to Country Byron Shire Council recognises the traditional owners of this land, the Bundjalung of Byron Bay, Arakwal people, the Widjabal people, the Minjungbul people and the wider Bundjalung Nation. We recognise that the most enduring and relevant legacy Indigenous people offer is their understanding of the significance of land and their local, deep commitment to place. The Byron Shire Residential Strategy respects and embraces this approach by engaging with the community and acknowledging that our resources are precious and must be looked after for future generations. Disclaimer This document is a draft for public comment. It should not be used as a basis for investment or other private decision making purposes about land purchase or land use. Initial consultation on landowner interest in the areas shown on the exhibited maps will occur during the exhibition process, but it must be understood that these maps may be subject to significant changes after the exhibition process, when adopted by Council and/or when endorsed by the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment. Therefore, potentially affected landowners are encouraged to remain informed and involved throughout the strategy process. This strategy has no status until formally adopted by Council and endorsed by the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment. Document history Doc no. Date amended Details (e.g. Resolution No.) E2018/111362 Pdf of Draft Strategy Presented to Council 13 Dec 2018 – Attachment 1 Resolution E2019/62759 Draft Strategy – public exhibition version (see E2018/112331 for background to edits) Table of Contents Section 1 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... -

The Meaning in Mullumbimby

The Meaning in Mullumbimby The first written record of ‘Mullumbimby’ in any spelling appeared in the NSW Government Gazette of 18Oct1872 with its reference to ‘Mullumbimby Creek’, viz Reserved From Sale As A Site For Village.... County of Rous, at the head of Boat Navigation, at the confluence of Mullumbimby Creek with the Brunswick River, Middle Arm, containing 640 acres..., ~75% of which was on the west of the river/creek. 'Chincogan Mountains' from the South Spit at Brunswick Heads 1921. Casino-based surveyor Richard Barling had turned up to reserve this site because of fear of a land rush following Robert Marshall’s application for Portion 1 along King’s Creek in the yet to be named ‘Parish of Brunswick’. James Bray, Crown Land Agent on the Tweed, had urged that a proper officer be sent (or instructions issued to Surveyor Barling) to lay out village and other necessary reserves before the spots best adapted for such purposes are pounced upon by intending purchasers.... After marking-out a village reserve at the Brunswick Heads in Apr1872 it’s likely Barling was pointed upstream past Marshall's place to an old settlement, where for some time past sectioned cedar logs had been rafted to the heads, apparently after being reworked into squared ‘planks’. By the time Barling turned up this ‘Myocum Depot’ was a place of considerable cedar activity, conveniently established on one of the ubiquitous ‘Grasses’*, providing a smorgasbord for hungry bullocks as well as a focal point for the jinker tracks from Tyagarah, Coorabell, Montecollum and Wilson’s Creek. -

Tweed Shire Echo

THE TWEED Volume 2 #41 Thursday, June 24, 2010 Advertising and news enquiries: Phone: (02) 6672 2280 [email protected] [email protected] www.tweedecho.com.au LOCAL & INDEPENDENT page 10 Council backflips on illegal clearing Kate McIntosh ing significant Aboriginal heritage value. Tweed Shire Council has backed The destruction of the tree, which down on plans to pursue legal action is subject to a council tree preserva- over the alleged wilful destruction tion order, is currently being inves- and illegal clearing of trees, including tigated by the NSW Department of a sacred Aboriginal tree and other Environment and Climate Change vegetation at the site of a proposed (DECCW). industrial estate near Pottsville. Chief planner Vince Connell told A council report has recommended The Echo council officers had drawn against taking legal action on the mat- on their substantial expertise and pro- ter in favour of a negotiated settle- fessional judgement in forming their Performing ment with landowners Tagget. recommendations. Council also deferred a decision on ‘Officers are obliged to weigh up arts festival a revised rezoning proposal for the the technical merits of any legal ad- site exempting areas of environmental vice provided and any wider policy or sensitivity, including illegally cleared precedent implications, as well as the a stairway to land, pending further consultation possible financial impacts to council on the matter. and the Tweed ratepayers in any rec- stardom The recommendation follows legal ommendation for substantive legal advice received from council solici- action,’ he said. Mime performer Ashlee Pollecutt from Lindisfarne Anglican Grammar School at the Murwillumbah Festival of Per- tors, the details of which are confiden- No council decision has been made forming Arts. -

Northern Rivers Region of New South Wales

SOCIO-ECONOMIC CHANGE ANALYSIS Karl Bock & David Brunckhorst Coping with Sea Change: Understanding Alternative Futures for Designing more Sustainable Regions (LWA UNE 54) Institute for Rural Futures Identifying socio-economic trends for the Northern Rivers Region of New South Wales Institute for Rural Futures Page 2 Institute for Rural Futures Page 3 1.0 Introduction The Northern Rivers region is undergoing substantial social and economic change due to the effects of population shifts, global competition and industry restructuring. The rapid increase in the region’s population, together with changing land use is impacting on the Northern Rivers’ natural environment, natural resources and on major infrastructure requirements of the region. These pressures are creating numerous negative impacts on the unique features of the region (such as the rural and natural landscapes, rural activities, and diverse cultural and lifestyle opportunities) that are highly valued by current residents and visitors. This report provides an overview of socio-economic trends using key social change indicators for the Northern Rivers Region of New South Wales. This work forms part of a larger project titled “Coping with Sea Change: Understanding Alternative Futures for Designing more Sustainable Regions”. The social-spatial trends identified in this work will aid in the development of trajectories that will be used to create a series of landscape change scenarios for the Northern Rivers Region. The data used in this document has been sourced from the Australian Population and Housing Census for the periods 1981, 1991 and 2001 (ABS 1989; ABS 1994; ABS 2003). A change analysis for each key socio-economic indicator was undertaken for the periods 1981 to 1991, 1991 to 2001 and overall change between 1981 to 2001.