Pen Park Hole Biological Report 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wessex Cave Club Journal Volume 24 Number 261 August 1998

THE WESSEX CAVE CLUB JOURNAL VOLUME 24 NUMBER 261 AUGUST 1998 PRESIDENT RICHARD KENNEY VICE PRESIDENTS PAUL DOLPHIN Contents GRAHAM BALCOMBE JACK SHEPPARD Club News 182 CHAIRMAN DAVE MORRISON Windrush 42/45 Upper Bristol Rd Caving News 182 Clutton BS18 4RH 01761 452437 Swildon’s Mud Sump 183 SECRETARY MARK KELLAWAY Ceram Expedition 183 5 Brunswick Close Twickenham Middlesex NCA Caver’s Fair 184 TW2 5ND 0181 943 2206 [email protected] Library Acquisitions 185 TREASURER & MARK HELMORE A Fathers Day To Remember 186 MRO CO-ORDINATOR 01761 416631 EDITOR ROSIE FREEMAN The Rescue of Malc Foyle 33 Alton Rd and His Tin Fish 187 Fleet Hants GU13 9HW Things To Do Around The Hut 189 01252 629621 [email protected] Observations in the MEMBERSHIP DAVE COOKE St Dunstans Well and SECRETARY 33 Laverstoke Gardens Ashwick Drainage Basins 190 Roehampton London SW15 4JB Editorial 196 0181 788 9955 [email protected] St Patrick’s Weekend 197 CAVING SECRETARY LES WILLIAMS TRAINING OFFICER & 01749 679839 Letter To The Membership 198 C&A OFFICER [email protected] NORTHERN CAVING KEITH SANDERSON A Different Perspective 198 SECRETARY 015242 51662 GEAR CURATOR ANDY MORSE Logbook Extracts 199 HUT ADMIN. OFFICER DAVE MEREDITH Caving Events 200 HUT WARDEN ANDYLADELL COMMITTEE MEMBER MIKE DEWDNEY-YORK & LIBRARIAN WCC Headquarters, Upper Pitts, Eastwater Lane SALES OFFICER DEBORAH Priddy, Somerset, BA5 3AX MORGENSTERN Telephone 01749 672310 COMMITTEE MEMBER SIMON RICHARDSON © Wessex Cave Club 1998. All rights reserved ISSN 0083-811X SURVEY SALES MAURICE HEWINS Opinions expressed in the Journal are not necessarily those of the Club or the Editor Club News Caving News Full details of the library contents are being Swildon’s Forty - What was the significance of the painstakingly entered by the Librarian onto the 10th July this year? WCC database. -

Dave Turner Caving

Dave Turner’s Caving Log Date Day Category Subcat Time Country Region Cave Description Accompanied by 61-?-? Sat Caving Trip UK Mendips Goatchurch 61-?-? Sat Caving Trip UK Mendips Rod's Pot 61-?-? ? Caving Trip UK Mendips Swildons Hole Top of 20' 61-?-? Wed Caving Trip UK Mendips Goatchurch 61-?-? Wed Caving Trip UK Mendips East Twin 61-?-? Wed Caving Trip UK Mendips Hunter's Hole 62-1-7 Wed Caving Trip UK Mendips Goatchurch 62-1-7 Wed Caving Trip UK Mendips Rod's Pot Aven 62-1-24 Wed Caving Trip UK Mendips Swildons Hole Top of 40' 62-1-28 Sun Caving Trip UK Mendips Lamb Leer Top of pitch 62-1-28 Sun Caving Trip UK Mendips Swildons Hole Mud Sump 62-2-3 Sat Caving Trip UK Mendips St. Cuthbert's Swallet 62-2-4 Sun Caving Trip UK Mendips Attborough Swallet (MNRC dig) 62-2-11 Sun Caving Trip UK Mendips Hilliers Cave 62-2-17 Sat Caving Trip UK Mendips Swildons Hole Shatter Pot and Sump 1 62-2-18 Sun Caving Trip UK Mendips GB Cave 62-2-24 Sat Caving Trip UK Mendips Longwood Swallet 62-2-25 Sun Caving Trip UK Mendips Balch's Cave 62-2-25 Sun Caving Trip UK Mendips Furnhill 62-3-10 Sat Caving Trip UK Mendips Gough's Cave 62-3-17 Sat Caving Trip 09:30 UK Mendips Swildons Hole Vicarage Pot Forest of 62-3-24 Sat Caving Trip UK Dean Iron Mine Forest of 62-3-25 Sun Caving Trip UK Dean Iron Mine 62-3-28 Wed Caving Trip UK Mendips Swildons Hole Sump 1 62-4-28 Sat Caving Trip UK Mendips Attborough Swallet 62-4-29 Sun Caving Walk UK Mendips Velvet Bottom 62-5-5 Sat Caving Trip UK Mendips Swildons Hole Vicarage Pot and Sump 2 62-5-6 Sun Caving Visit UK -

Palaeolithic and Pleistocene Sites of the Mendip, Bath and Bristol Areas

Proc. Univ. Bristol Spelacol. Soc, 19SlJ, 18(3), 367-389 PALAEOLITHIC AND PLEISTOCENE SITES OF THE MENDIP, BATH AND BRISTOL AREAS RECENT BIBLIOGRAPHY by R. W. MANSFIELD and D. T. DONOVAN Lists of references lo works on the Palaeolithic and Pleistocene of the area were published in these Proceedings in 1954 (vol. 7, no. 1) and 1964 (vol. 10, no. 2). In 1977 (vol. 14, no. 3) these were reprinted, being then out of print, by Hawkins and Tratman who added a list ai' about sixty papers which had come out between 1964 and 1977. The present contribution is an attempt to bring the earlier lists up to date. The 1954 list was intended to include all work before that date, but was very incomplete, as evidenced by the number of older works cited in the later lists, including the present one. In particular, newspaper reports had not been previously included, but are useful for sites such as the Milton Hill (near Wells) bone Fissure, as are a number of references in serials such as the annual reports of the British Association and of the Wells Natural History and Archaeological Society, which are also now noted for the first time. The largest number of new references has been generated by Gough's Cave, Cheddar, which has produced important new material as well as new studies of finds from the older excavations. The original lists covered an area from what is now the northern limit of the County of Avon lo the southern slopes of the Mendips. Hawkins and Tratman extended that area to include the Quaternary Burtle Beds which lie in the Somerset Levels to the south of the Mendips, and these are also included in the present list. -

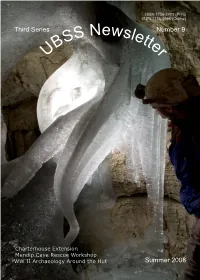

UBSS Newsletter Third Series Volume 1 No 9

ISSN 1756-2988 (Print) ISSN 1756-2996 (Online) Third Series S Newsle Number 9 BS tte U r Charterhouse Extension Mendip Cave Rescue Workshop WW II Archaeology Around the Hut Summer 2008 UBSS Newsletter Third Series Number 9 The Charterhouse Cave Extension The Charterhouse extension looking downstream from the Blades (the stream is flowing under the floor of the passage). Photo: Pete Hann The UBSS team working in Great we sub-contracted the dig to our Graham (another of the 80s Swallet have missed the big prize club mate Pete Hann and set our diggers) undertaking cementing and, now that Charterhouse Cave sights elsewhere on Mendip. Pete trips each fortnight. I was happy to has gone, Bat Dig in GB certainly had dug with Willie Stanton and he give moral support from my does deserve the accolade “Best copied the methods Willie employed armchair. Then in April, with Ali potential in Mendips”, though that at Reservoir Hole. Cement complaining that the team were potential has been rather diminished. everything in sight, remove the having trouble finding enough But it is not all doom and gloop, the boulders blocking the way, move ballast in the splash pools through Society did have a representative forward, cement everything in sight, the cave for the concrete, I foolishly embedded in the successful team of remove the boulders blocking the suggested that instead of wasting Wessex Cave Club diggers at way, move forward and repeat again, an hour or so each trip sieving grit, Charterhouse. What follows is my again and again. It is very effective they bring gravel in from the surface. -

Somerset Geology-A Good Rock Guide

SOMERSET GEOLOGY-A GOOD ROCK GUIDE Hugh Prudden The great unconformity figured by De la Beche WELCOME TO SOMERSET Welcome to green fields, wild flower meadows, farm cider, Cheddar cheese, picturesque villages, wild moorland, peat moors, a spectacular coastline, quiet country lanes…… To which we can add a wealth of geological features. The gorge and caves at Cheddar are well-known. Further east near Frome there are Silurian volcanics, Carboniferous Limestone outcrops, Variscan thrust tectonics, Permo-Triassic conglomerates, sediment-filled fissures, a classic unconformity, Jurassic clays and limestones, Cretaceous Greensand and Chalk topped with Tertiary remnants including sarsen stones-a veritable geological park! Elsewhere in Mendip are reminders of coal and lead mining both in the field and museums. Today the Mendips are a major source of aggregates. The Mesozoic formations curve in an arc through southwest and southeast Somerset creating vales and escarpments that define the landscape and clearly have influenced the patterns of soils, land use and settlement as at Porlock. The church building stones mark the outcrops. Wilder country can be found in the Quantocks, Brendon Hills and Exmoor which are underlain by rocks of Devonian age and within which lie sunken blocks (half-grabens) containing Permo-Triassic sediments. The coastline contains exposures of Devonian sediments and tectonics west of Minehead adjoining the classic exposures of Mesozoic sediments and structural features which extend eastward to the Parrett estuary. The predominance of wave energy from the west and the large tidal range of the Bristol Channel has resulted in rapid cliff erosion and longshore drift to the east where there is a full suite of accretionary landforms: sandy beaches, storm ridges, salt marsh, and sand dunes popular with summer visitors. -

Wessex-Cave-Club-Journal-Number

Vol. 17 No. 193 CONTENTS page Editorial 27 Letter to the Editor Bob Lewis 27 Longwood – The Renolds Passage Extension Pete Moody 28 Caving on a Coach Tour, 1982 Paul Weston 32 Charterhouse Caving Committee Phil Hendy 35 The Works Outing Sanity Clause 36 Book Review; Northern Caves Volumes Two and Three Steve Gough 37 From The Log 37 CLUB OFFICERS Chairman Philip Hendy, 10 Silver St., Wells, Somerset. Secretary Bob Drake, Axeover House, Yarley, Nr. Wells, Somerset. Asst. Secretary Judith Vanderplank, 51 Cambridge Road, Clevedon, Avon Caving Secretary Jeff Price, 18 Hurston Road, Inns Court, Bristol. Asst. Caving Sec. Keith Sanderson, 11 Pye Busk Close, High Bentham, via Lancaster. (Northern caves only) Treasurer Jerry (Fred) Felstead, 47 Columbine Road, Widmer End, High Wycombe, Bucks. Gear Curator Dave Morrison, 27 Maurice Walk, London NW 11 HQ Warden Glyn Bolt, 4 The Retreat, Foxcote, Radstock, Avon. HQ Administration John Ham, The Laurels, East Brent, Highbridge, Som. Editor Al Keen, 88 Upper Albert Road, Sheffield, S8 9HT Sales Officer Barry Davies, 2 North Bank, Wookey Hole, Wells, Som. HQ Bookings Adrian Vanderplank, 51 Cambridge Road, Clevedon, Avon Librarians Pete & Alison Moody Survey Sales Maurice Hewins (c) Wessex Cave Club 1982 Price to non-members 60p inc. P&P. Vol. 17 No. 193 EDITORIAL If there is such a thing as a silly season for editorials, then this is it. I have recently moved back to London after changing jobs, and I have also been preparing for a few weeks abroad, all of which has left little time even to think of this padding! There is no 'Mendip News' or 'Club News' in this issue, as activity since the last reports is continuing on much the same lines. -

(P5) 6 01379 6 12/08/1955 Easter Hole Mendip 7 01379 6 13/08/1955 Tankard Hole Mendip Dig 8 01379 7 14/08/1955 Easter Hole Mendip Dig 9 01379 9 13/08/1955 G.B

WESSEX CAVE CLUB LOGBOOK CAVING LOGBOOK 1955 - 1956 No. Acq. No. Page Date Cave Area Notes Survey Significant 1 01379 2 06/08/1955 Cuckoo Cleeves Mendip Dig 2 01379 2 07/06/1955 Cuckoo Cleeves Mendip Dig 3 01379 2 07/08/1955 Swildon's Hole Mendip 4 01379 3 10/08/1955 Eastwater Cavern Mendip 5 01379 4 11/08/1955 Easter Hole Mendip Dig P (p5) 6 01379 6 12/08/1955 Easter Hole Mendip 7 01379 6 13/08/1955 Tankard Hole Mendip Dig 8 01379 7 14/08/1955 Easter Hole Mendip Dig 9 01379 9 13/08/1955 G.B. Cave Mendip 10 01379 10 14/08/1955 Cuckoo Cleeves Mendip Dig, survey 11 01379 12 14/08/1955 Easter Hole Mendip P 12 01379 13 15/08/1955 Easter Hole Mendip Dig 13 01379 14 16/08/1955 Dallimore's Cave Mendip 14 01379 14 18/08/1955 Swildon's Hole Mendip 15 01379 14 19/08/1955 Hunters' Hole Mendip 16 01379 14 20/08/1955 Cuckoo Cleeves Mendip Surveying 17 01379 15 20/08/1955 Swildon's Hole Mendip Crystal Passage dig 18 01379 16 21/08/1955 Swildon's Hole Mendip Priddy Pool Passage dig 19 01379 16 25/08/1955 Swildon's Hole Mendip 20 01379 17 26/06/1955 St. Cuthbert's Swallet Mendip Surveying 21 01379 17 27/08/1955 Lamb Leer Cavern Mendip 22 01379 18 28/08/1955 Cuckoo Cleeves Mendip Exploration, photography 23 01379 18 28/08/1955 Hillier's Cave Mendip Recce. 24 01379 19 03/09/1955 Swildon's Hole Mendip Bail Muddy Sump 25 01379 20 04/09/1955 Stoke Lane Slocker Mendip 26 01379 20 06/09/1955 Eastwater Cavern Mendip 27 01379 21 07/09/1955 'Skeleton Shaft' Mendip Sandford Hill 28 01379 21 07/09/1955 Pearl Mine Mendip 29 01379 21 08/09/1955 Midway Slocker Mendip -

WSG NL July 2012, Final, Public

2012/03 JULY Westminster Spelæological Group Cave Exploration and Investigation President: Toby Clark esq. Newsletter No. 2012/3 Photo: Laura ! PAGE 1 2012/03 JULY July 2012 Edition Welcome to the July 2012 Newsletter. Here is the news. Ben & Robyn’s Wedding Congratulations to Robyn and Ben! In Robyn’s own words: I married Ben Lovett on the 11th May on the Isle of Mull in Scot- land. It was a small wedding and in true caving fashion, the wedding cake had two caving helmets on the top for the bride and groom. AGM The 62nd Annual General Meeting took place on 23rd June and was a quiet success. De- spite ample opportunity for animated misunderstanding, serious matters were addressed. More than one member commented on the level-headed atmosphere. Who knew? New Faces in the Cabinet Reshufe Chris, Robyn & Rupert stepped down from their positions on the committee. Chris left after a five(?) years as a committee member; Robyn after becoming a mum and Australian to-be; and Rupert to be elevated to Chair. Eagerly filling the power vacuum, Steve L. was elected Hon. Secretary and Amy P. was the next day voted in Caving Secretary. Many thanks once again to Chris and Robyn for their good work. New faces Down Under Farewell Robyn and Ben who are emigrating to Tasmania. We wish you the best of luck in your new life. Au revoir Fay who will be working and travelling in New Zealand for the next six months. Have a great time and please remember to come back! Enjoy the Newsletter. -

Radon Gas in Caves of the Peak District

University of Huddersfield Repository Hyland, Robert Quentin Thomas. Spatial and temporal variations of radon and radon daughter concentrations within limestone caves Original Citation Hyland, Robert Quentin Thomas. (1995) Spatial and temporal variations of radon and radon daughter concentrations within limestone caves. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/4839/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ SPATIAL AND TEMPORAL VARIATIONS OF RADON AN]) RADON DAUGHTER CONCENTRATIONS WITHIN LIMESTONE CAVES BY ROBERT QIJENTIN THOMAS IIYLAND A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fhlflhlment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of -

Journal of the Wessex Cave Club Vol

Journal of the Wessex Cave Club Vol. 29. No. 309 February 2008 President Donald Thomson Vice Presidents Sid Perou Derek Ford Chairman The eagle-eyed amongst you may have noticed that we have a colour cover to this David Morrison Journal. The quality of the photographs which you send for the Journal make this Windrush a constant temptation, but this was irresistible. All my Editorial work and musings Upper Bristol Road pale into utter insignificance when one reads The Swildons Book. I suspect that Clutton BS395RH it bound to be known to us as “The Swildons Book”, rather than by its title, and 01761 452 437 that that is proper. And it is right that it should feature on this Journal, because it Secretary must represent as big a landmark in the Wessex Cave Club history as the move Kevin Hilton to Upper Pitts. I had hoped to be able to publish a professional review in this 63 Middlemarsh Street, Poundbury, Journal. Everyone I approached claimed that they were either under-qualified, or Dorchester, over-involved, or both, as do I myself. So in lieu I’ve printed a (small) selection Dorset DT1 3FD of the Emails and various Forum messages received by Ali. There’s no mistaking 01305 259274 the overall impression of delight and amazement that the book has engendered. Membership Secretary And it must be remembered that the very considerable work of receiving book Charlotte Kemp orders, packaging and despatching them is still falling on Ali and Brian Prewer. Treasurer David Cooke Speaking personally, first thing I did was to look at the index to see if my name Caving Secretary Les Williams were there; being, like scores of fellow cavers, fascinated and vain. -

Wessex-Cave-Club-Journal-Number

Journal No. 169 Volume 14 1977 CONTENTS Page Editorial 145 Club News 145 NCA Equipment Information 147 SRT Casualty Recovery P.L. Hadfield 148 Upper Pitts Progress P.G. Hendy 151 A Near Miss P.L. Hadfield 151 Recent Work in Stoke Lane Slocker A.D. Mills 152 A Song for Exponents of SRT 153 Otter Hole – Risks of Flooding P.L. Hadfield 153 Equipment Notes P.L. Hadfield 154 From the Log 155 Hon. Secretary: P.G. Hendy, 5 Tring Avenue, Ealing Common, London W. 5. Asst. Secretary: I. Jepson, 7 Shelley Road, Beechen Cliff, Bath, Avon. Caving Secretary: J.R. Price, 18 Hurston Road, Inns Court, Bristol, BS4 1SU. Asst. Caving Secretary: K.A. Sanderson, 11 Pye Busk Close, High Bentham, via Lancaster. (Northern Caves Only) Hon. Treasurer: B.C. Wilkinson, 421 Middleton Road, Carshalton, Surrey. Gear Curator: B. Hansford, 19 Moss Road, Winnall, Winchester, Hants. Hut Admin. Officer: W.J. Ham, “The Laurels”, East Brent, Highbridge, Somerset. Hut Warden: P.L. Hadfield, 6 Haycroft Road, Stevenage Old Town, Herts. Deputy Hut Warden: J. Penge, 4 Chelmer Grove, Keynsham, Avon. Publication Sales: R.R. Kenney, “Yennek”, St. Mary’s Road, Meare, Glastonbury, Somerset. General Sales: R.A. Websell, Riverside House, Castle Green, Nunney, Somerset. Editor: A.R. Audsley, Lawn Cottage, Church Lane, Three Mile Cross, Reading, Berks. P.G. Hendy and P.l. Hadfield temporary joint editors for Nos. 169 and 170. Journal Distribution: M. Darville, 30 Ashgrove Avenue, Ashley Down, Bristol BS7 9LL. Journal price for non-members: 30p per issue. Postage 12p extra © WESSEX CAVE CLUB 1977 EDITORIAL In spite of extensive efforts to find a temporary Editor for this journal, the Committee was forced to apply the principle that if you want a job done, either find a busy man, or do it yourself. -

Upper Pitts 1992-1994

WESSEX CAVE CLUB CAVING LOGBOOK 1992 - 1994 Acq. No. No. Page Date Cave Area Notes Survey Significant 00526 1 1 31/01/1992 Eastwater Cavern Mendip 00526 2 1 29/01/1992 Flower Pot Mendip 00526 3 1 31/01/1992 Hunters' Hole Mendip 00526 4 1 01/02/1992 Swildon's Hole Mendip Round Trip, Four, Lower Fault Chamber 00526 5 0 02/02/1992 Ogof Ffynnon Ddu Wales Two 00526 6 1 01/02/1992 Swildon's Hole Mendip Mud Sump 00526 7 1 01/02/1992 County Pot Yorkshire 00526 8 2 04/02/1992 Wheel Pit Mendip Surface 00526 9 2 04/02/1992 Waldegrave Swallet Mendip Surface 00526 10 2 04/02/1992 Cuckoo Cleeves Mendip 00526 11 2 05/02/1992 Swildon's Hole Mendip Blue Pencil Passage 00526 12 2 05/02/1992 Flower Pot Mendip Dig 00526 13 2 07/02/1992 Welsh's Green Swallet Mendip 00526 14 2 09/02/1992 Longwood Swallet / August Hole Mendip 00526 15 3 12/02/1992 Flower Pot Mendip Dig 00526 16 3 12/02/1992 Eighteen Acre Swallet Mendip Dig 00526 17 3 14/02/1992 Swildon's Hole Mendip Black Hole, Sump II 00526 18 3 15/02/1992 Swildon's Hole Mendip Upper Series photography 00526 19 3 15/02/1992 Swildon's Hole Mendip Short Round Trip 00526 20 3 16/02/1992 G.B. Cave Mendip Bat Passage 00526 21 3 15/02/1992 Swildon's Hole Mendip Pirate Chamber 00526 22 4 20/02/1992 Swildon's Hole Mendip 00526 23 4 15/02/1992 Peak Cavern Derbyshire White River Series 00526 24 5 16/02/1992 Tilly Whim Caves Dorset Survey 00526 25 5 22/02/1992 Swildon's Hole Mendip Four 00526 26 5 21/02/1992 Pinetree Pot Mendip 00526 27 5 22/02/1992 Longwood Swallet / August Hole Mendip 00526 28 5 22/02/1992 Swildon's Hole Mendip 00526 29 5 22/02/1992 Little Neath River Cave Wales 00526 30 6 22/02/1992 Swildon's Hole Mendip Two 00526 31 6 23/02/1992 Swildon's Hole Mendip Hensler's Dig (dig) 00526 32 6 27/02/1992 Flower Pot Mendip 00526 33 7 29/02/1992 St.