KEMP & KEMP PRACTICE NOTES: INSOLVENT DEFENDANTS Simon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

You Never Saw a Fish on the Wall with Its Mouth Shut

IAN WINTER QC YOU NEVER SAW A FISH ON THE WALL WITH ITS MOUTH SHUT THE PRIVILEGE AGAINST SELF-INCRIMINATION AND THE DECISION OF THE COURT OF APPEAL IN R V K [2009] EWCA CRIM 1640 ISSUE NINE WINTER 2009 PUBLISHED BY CLOTH FAIR CHAMBERS CLOTH FAIR CHAMBERS Nicholas Purnell QC Richard Horwell QC John Kelsey-Fry QC Timothy Langdale QC Ian Winter QC Jonathan Barnard Clare Sibson Cloth Fair Chambers specialises in fraud and commercial crime, complex and organised crime, regulatory and disciplinary matters, defamation and in broader litigation areas where specialist advocacy and advisory skills are required. 2 CLOTH FAIR CHAMBERS IAN WINTER QC YOU NEVER SAW A FISH ON THE WALL WITH ITS MOUTH SHUT1 THE PRIVILEGE AGAINST SELF-INCRIMINATION AND THE DECISION OF THE COURT OF APPEAL IN R V K [2009] EWCA CRIM 1640 ISSUE NINE WINTER 2009 PUBLISHED BY CLOTH FAIR CHAMBERS 1 Unreliably attributed to Sally Berger but the true origin is unclear. King John, pressured by the barons and threatened with insurrection, reluctantly signs the great charter on the Thames island of Runnymede CLOTH FAIR CHAMBERS he fish on the wall has its mouth open unreliable testimony produced as a result of it. because it couldn’t resist the temptation to open it when the occasion appeared to Had paragraph 38 of Magna Carta remained the law, which justify doing so. There are few convicted could have been the case even once the use of torture had defendants who likewise could resist the been outlawed2, the question over the admissibility of the temptation to open their mouths and accused’s statement would not have been whether the Tthereby assist their prosecutors with their own words. -

![In Re Lehman Bros International (Europe) (No 4) (Ch D)[2014] 3 WLR](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4968/in-re-lehman-bros-international-europe-no-4-ch-d-2014-3-wlr-894968.webp)

In Re Lehman Bros International (Europe) (No 4) (Ch D)[2014] 3 WLR

466 In re Lehman Bros International (Europe) (No 4) (Ch D)[2014] 3 WLR Chancery Division A In re Lehman Bros International (Europe) (in administration) (No 4) [2014] EWHC 704 (Ch) B 2013 Nov 12—15, 18—20; David Richards J 2014 March 14 Insolvency Ñ Administration Ñ Distribution of assets Ñ Ranking of claims which might be made against available assets of unlimited company after payment of general unsecured unsubordinated creditors Ñ Potential liability of members for liabilities of company Ñ Relationship between liability as members and claims as creditors Ñ Whether claim of subordinated debt holder ranking ahead of or C behind statutory interest Ñ Whether claim ranking ahead of or behind foreign currency conversion claims Ñ Whether foreign currency conversion claims payable out of assets Ñ Whether contractual interest provable or statutory interest payable for period of administration if immediately followed by liquidation Ñ Whether members liability to contribute in liquidation limited to funds required to pay debts and liabilities proved in liquidation Ñ Whether contributory rule applying in administration Ñ Insolvency Act 1986 (c 45) D (as amended by Companies Act 2006 (Consequential Amendments, Transitional Provisions and Savings Order 2009 (SI 2009/1941), Sch 1, para 75(3)), ss 74, 189 Ñ Insolvency Rules 1986 (SI 1986/1925) (as amended by Insolvency (Amendment) Rules 2003 (SI 2003/1730), Sch 1, para 9 and Insolvency (Amendment) Rules 2005 (SI 2005/1730), r 12), r 2.88(1)(7) The applicants were the joint administrators of three companies in the same E group: LBIE, the principal trading company, which was an unlimited company, and its two members, LBL and LBHI2. -

Dear IP 48 Coverpage, December 2010

Dear IP April 2020 – Issue No 94 Insolvency Practitioner Regulation Section 16th Floor 1 Westfield Avenue Stratford London E20 1HZ Tel: 020 7291 6771 www.gov.uk/government/organisations/insolvency- service DEAR INSOLVENCY PRACTITIONER Issue 94 – April 2020 Message from Angela Crossley, Head of Insolvency Practitioner Regulation Dear Reader Please fined enclosed the latest main issue of Dear IP. The Insolvency Service is also issuing weekly publications to our readership regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. Whilst every effort is made to ensure that the information provided is accurate, the contents of Dear IP are, unless stated otherwise, the view of the Insolvency Service, and articles are not a full and authoritative statement of law Dear IP April 2020– Issue No 94 In this issue: Information/Notes page(s): Chapter 12 Gazette and Advertisement Article 10 Placing Gazette notices: a reminder Chapter 13 General Article 102 Joint statement from the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) and the Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS), warning insolvency practitioners and FCA-authorised firms to be responsible when dealing with personal data Article 103 Insolvency Code of Ethics Chapter 15 Insolvency Rules, Regulations and Orders Article 67 An increase in the cap on the prescribed part with effect from 6 April 2020 – The Insolvency Act 1986 (Prescribed Part) (Amendment) Order 2020 Dear IP April 2020 – Issue No 94 Chapter 12 - Gazette and Advertisement 10) Placing Gazette notices: a reminder As an authorised notice placer, insolvency practitioners can place insolvency notices in The Gazette via email, post, fax, web form or XML. -

Can a Struggling Company Ever Justify Paying Some - but Not All - of Its Creditors?

CAN A STRUGGLING COMPANY EVER JUSTIFY PAYING SOME - BUT NOT ALL - OF ITS CREDITORS? In light of the financially fragile state some businesses are finding themselves in as result of COVID-19, we discuss in this briefing note when – if ever – payments or other benefits can be given to some creditors but not others, and when such a transaction might fall foul of the unlawful preference provisions of UK insolvency legislation. This is a fast-moving area and this briefing note sets out the position as at 7 April 2020. WHY ARE TRANSACTIONS CHALLENGED? When a company enters a formal insolvency procedure, the insolvency practitioner appointed Unlawful preference as liquidator or administrator of the company will review the transactions into which the transactions can be company entered in the run-up to its insolvency. They will then assess whether any of those unwound, leading to transactions might be challenged under the ‘antecedent transactions’ provisions of UK court orders to repay insolvency legislation. This provides an opportunity to bring money or other assets back into funds or return the company’s estate, which increases the pool of assets from which a distribution can be property. made to the company’s creditors. WHAT IS AN UNLAWFUL PREFERENCE? An unlawful preference can be challenged by an administrator or liquidator under section 239 of the Insolvency Act 1986 (the “Insolvency Act”). Under these provisions, a company gives a preference if: • the company does anything (or suffers anything to be done) which has the effect of putting -

FREEDOM of INFORMATION ACT Previously Released Information

FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT Previously released information / disclosure log FY 2016–2017 NOTES Logs are updated at the end of each quarter Questions are produced in their original format TOPIC PAGE 1ST QUARTER 1) Civil complaint 4 2) Breaches of the Data Protection Act 7 3) Matters relating to deceased mother’s estate 10 4) Misconduct in public office 10 5) Tribunals 22 6) (a) Court of Appeal; (b) Immunity of Councils 24 7) Solicitors signing documents 26 8) Law applicable to contractual obligations 26 9) Debt or liability 27 10) GOV.UK 28 11) Council Tax 28 12) Council tax statutory demands and bankruptcy petitions 29 13) IT structure 30 14) Local authorities 30 15) Common law jurisdiction 31 1 2ND QUARTER 16) Withdrawal of the UK from the EU 31 17) Earnings 32 18) Security and fire products and services 33 19) Electoral law 33 20) Contracts 34 21) ICT expenditure 35 22) Common law jurisdiction (internal review) 36 23) Can a regulation (secondary legislation) change primary legislation? 37 24) Council Tax (internal review) 38 25) Categories of person registered by the Law Society 40 26) Common law jurisdiction 41 27) Easements 41 28) Publication policy 41 29) Magna Carta / lawful rebellion 42 3RD QUARTER 30) Electoral law 42 31) Legal definition 45 32) Software contracts 45 33) Implementation of Law Commission reports 46 34) Legal requirement to notify the Land Registry of bankruptcy 46 35) Misconduct in public office 48 2 4TH QUARTER 36) Prescribed creditor’s insolvency forms for bankruptcy 55 37) Accounts and IT questions (various) -

An Introduction to Corporate Insolvency Law

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk The Plymouth Law & Criminal Justice Review The Plymouth Law & Criminal Justice Review, Volume 08 - 2016 2016 An Introduction to Corporate Insolvency Law Anderson, Hamish Anderson, H. (2016) 'An Introduction to Corporate Insolvency Law',Plymouth Law and Criminal Justice Review, 8, pp. 16-47. Available at: https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk/handle/10026.1/9038 http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/9038 The Plymouth Law & Criminal Justice Review University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. Plymouth Law and Criminal Justice Review (2016) 1 AN INTRODUCTION TO CORPORATE INSOLVENCY LAW Hamish Anderson1 Abstract English law provides three forms of insolvency proceeding for companies: liquidation, administration and company voluntary arrangements. This paper begins by examining the nature and purpose of insolvency law, the concepts of insolvency and insolvency proceedings, how insolvency practice is regulated and the role of the court. It then considers the sources of the law before describing the distinguishing characteristics of liquidation, administration and company voluntary arrangements. Finally, it deals with the sanctions for malpractice, transaction avoidance and cross-border insolvency. Keywords: insolvency, liquidation, administration, company voluntary arrangement, office- holder, wrongful trading, fraudulent trading, director disqualification, transaction avoidance Introduction This paper is a high level introduction to corporate insolvency law for students of company law. -

Sub-Committee on Insolvency

THE LAW REFORM COMMISSION OF HONG KONG SUB-COMMITTEE ON INSOLVENCY CONSULTATIVE DOCUMENT ON BANKRUPTCY NOTICE THIS IS A CONSULTATIVE DOCUMENT, NOT A HONG KONG LAW REFORM COMMISSION REPORT. It explains aspects of the existing bankruptcy law in Hong Kong, its deficiencies, the identified options for reform, and the tentative views of the Law Reform Commission Insolvency Sub-committee. THE TENTATIVE VIEWS EXPRESSED IN THIS CONSULTATIVE DOCUMENT DO NOT REPRESENT THE FINAL VIEWS OF THE INSOLVENCY SUB-COMMITTEE NOR THOSE OF THE LAW REFORM COMMISSION. Comments on issues raised in the consultative document are welcome, but should be forwarded no later than 30 September 1993. Unless advised to the contrary, comments will not be treated as confidential nor subject to copyright preventing quotation in the final report of the Law Reform Commission. You are requested to direct all enquiries and comments to: The Secretary The Insolvency Sub-committee The Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong 1/F High Block Queensway Government Offices 66 Queensway Hong Kong THE LAW REFORM COMMISSION OF HONG KONG SUB-COMMITTEE ON INSOLVENCY CONSULTATIVE DOCUMENT ON BANKRUPTCY _______________________________________ CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. Introduction 1 Terms of Reference 1 Summary of Work 2 Method of Work 2 The Bankruptcy Ordinance (Cap 6) 2. Grounds for presenting a bankruptcy petition 5 Abolition of acts of bankruptcy 7 Failure to comply with a statutory demand 10 Unsatisfied execution of a judgment debt 11 Absconding debtors 11 Expediting the presentation of the petition 12 Individual voluntary arrangements 12 3. Jurisdiction of the court 15 Widening the jurisdiction 16 Having or likely to have assets in Hong Kong 19 Possibility of a benefit accruing 20 Bankruptcy jurisdiction 20 4. -

Durham E-Theses

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Durham e-Theses Durham E-Theses An Analysis of the Statutory Regulation of Fraudulent Trading SKUDRA, HENRY,MIKOLAJ How to cite: SKUDRA, HENRY,MIKOLAJ (2012) An Analysis of the Statutory Regulation of Fraudulent Trading, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3642/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk An Analysis of the Statutory Regulation of Fraudulent Trading Henry Mikolaj Skudra University College, University of Durham Research conducted at Durham Law School, University of Durham This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Jurisprudence. November 2011 Copyright Declaration All rights reserved. No part of this thesis may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, or stored in any retrieval system of any nature, without prior written permission. -

Liquidation and Insolvency

Liquidation and Insolvency GP08 February 2014 Insolvency Act 1986 This guidance is available in alternative formats which include Braille, large print and audio tape. For further details please email our enquiries section or telephone our contact centre on 0303 1234 500. Is this guidance for you? This guide will be relevant to you if you: • are a director or secretary of a company • act as an adviser to a company GP08 February 2014 - Version 3.9 Insolvency Act 1986 Page 2 of 26 GBW1Liquidation and Insolvency Contents Introduction Chapter 1. General information Chapter 2. Corporate voluntary arrangements (CVA) including CVA moratoria Chapter 3. In administration’ and ‘administration orders’ - Cases beginning on or after 15 September 2003: In administration Chapter 4. Receivers Chapter 5. Voluntary liquidation Chapter 6. Compulsory liquidation Chapter 7. European cross-border insolvency proceedings Chapter 8. Frequently asked questions Chapter 9. Quality of documents Chapter 10. Further information This guide answers many frequently asked questions and provides information on completing the most commonly used filings relating to this area. The guide is not drafted with unusual or complex transactions in mind. Specialist professional advice may be needed in those circumstances. GP08 February 2014 - Version 3.9 Insolvency Act 1986 Page 3 of 26 Introduction This guidance provides a basic overview of insolvency and liquidation proceedings and more detailed information about the documents that must be delivered to the Registrar of Companies. It summarises some of the rules that apply to corporate voluntary arrangements, moratoria, administrations, receivers, voluntary liquidations, compulsory liquidations and EC regulations. Companies House can assist with queries relating to the delivery of documents to the Registrar. -

Corporate Insolvency and Governance Bill Explanatory Notes

CORPORATE INSOLVENCY AND GOVERNANCE BILL EXPLANATORY NOTES What these notes do These Explanatory Notes relate to the Corporate Insolvency and Governance Bill as introduced in the House of Commons on 20 May 2020 (Bill 128). • These Explanatory Notes have been produced by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy in order to assist the reader. They do not form part of the Bill and have not been endorsed by Parliament. • These Explanatory Notes explain what each part of the Bill will mean in practice; provide background information on the development of policy; and provide additional information on how the Bill will affect existing legislation in this area. • These Explanatory Notes might best be read alongside the Bill. They are not, and are not intended to be, a comprehensive description of the Bill. Bill 128–EN 58/1 Table of Contents Subject Page of these Notes Overview of the Bill 7 Policy background 8 Moratorium 8 Arrangements and reconstructions for companies in financial difficulty 10 Winding-up petitions 14 Wrongful trading 17 Termination clauses in supply contracts 19 Power to amend corporate insolvency or governance legislation 23 Meetings and filing requirements 26 Meetings of companies and other bodies 26 Extension of filing deadlines 29 Legal background 30 Insolvency framework measures: moratorium, termination clauses, arrangements and reconstructions for companies in financial difficulty (restructuring plan) 30 Winding-up petitions 33 Wrongful trading 35 Power to amend corporate insolvency or governance legislation 36 These Explanatory Notes relate to the Corporate Insolvency and Governance Bill as introduced in the House of Commons on 20 May 2020 (Bill 128) 1 1 Meetings and filings 36 Territorial extent and application 38 Fast-track legislation 39 Commentary on provisions of Bill/Act 47 Moratorium 47 Clause 1: GB Moratoriums 47 Chapter 1: provides an overview of new Part A1 and introduces Schedule ZA1 47 Chapter 2: sets out how an eligible company may obtain a moratorium 50 Chapter 3: sets out how long a moratorium has effect. -

Exhibit List

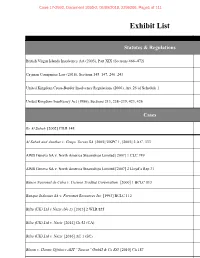

Case 17-2992, Document 1093-2, 05/09/2018, 2299206, Page1 of 111 Exhibit List Statutes & Regulations British Virgin Islands Insolvency Act (2003), Part XIX (Sections 466–472) B Cayman Companies Law (2016), Sections 145–147, 240–243 United Kingdom Cross-Border Insolvency Regulations (2006), Art. 25 of Schedule 1 United Kingdom Insolvency Act (1986), Sections 213, 238–239, 423, 426 Cases Re Al Sabah [2002] CILR 148 Al Sabah and Another v. Grupo Torras SA [2005] UKPC 1, [2005] 2 A.C. 333 AWB Geneva SA v. North America Steamships Limited [2007] 1 CLC 749 AWB Geneva SA v. North America Steamships Limited [2007] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 31 Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Cosmos Trading Corporation [2000] 1 BCLC 813 Banque Indosuez SA v. Ferromet Resources Inc [1993] BCLC 112 Bilta (UK) Ltd v Nazir (No 2) [2013] 2 WLR 825 Bilta (UK) Ltd v. Nazir [2014] Ch 52 (CA) Bilta (UK) Ltd v. Nazir [2016] AC 1 (SC) Bloom v. Harms Offshore AHT “Taurus” GmbH & Co KG [2010] Ch 187 Case 17-2992, Document 1093-2, 05/09/2018, 2299206, Page2 of 111 Exhibit List Cases, continued Re Paramount Airways Ltd [1993] Ch 223 Picard v. Bernard L Madoff Investment Securities LLC BVIHCV140/2010 B Rubin v. Eurofinance SA [2013] 1 AC 236; [2012] UKSC 46 Singularis Holdings Ltd v. PricewaterhouseCoopers [2014] UKPC 36, [2015] A.C. 1675 Stichting Shell Pensioenfonds v. Krys [2015] AC 616; [2014] UKPC 41 Other Authorities McPherson’s Law of Company Liquidation (4th ed. 2017) Anthony Smellie, A Cayman Islands Perspective on Trans-Border Insolvencies and Bankruptcies: The Case for Judicial Co-Operation , 2 Beijing L. -

Insolvency View February 2019

Insolvency View February 2019 Contents INSOLVENCY VIEW THE LATEST MAJOR CASES REVIEWED BY NEW p1 Sleight v The Crown Estate SQUARE CHAMBERS’ INSOLVENCY SPECIALISTS Commissioners: standing of a trustee in bankruptcy to apply for a vesting order Jessica Powers p3 Heidi Boulton v Queen Margaret’s School, York Limited : Unreasonable Sleight v The Crown Estate Commissioners: refusal of a compounding standing of a trustee in bankruptcy to apply part-offer Jeff Hardman for a vesting order Jessica Powers p4 Global Corporate Limited v Hale: The pitfalls of using [2018] EWHC 3489 (Ch) dividends to remunerate a High Court of Justice Business and Property Courts in Leeds shareholder/director Insolvency and Companies List (ChD) employee His Honour Judge Davis-White QC Hermione Williams 19 December 2018 p6 Horsley v HMRC: the right to It is not at all uncommon for a trustee in appeal pre-bankruptcy tax bankruptcy to disclaim onerous property. But what assessments happens when that property is subsequently Kristina Lukacova realised such as to create a surplus; can a trustee in bankruptcy apply for a vesting order in respect p7 Pearse v HMRC: serving a statutory demand despite a of that surplus? guarantee excluding bankruptcy proceedings Facts James McKean Jillian Mascall passed away on 4 December 2014. Upon realising that the estate was insolvent, the Latest Updates executrix petitioned for an insolvency administration To receive the latest updates order. That order was granted on 22 December 2015, from our Insolvency team, and James Sleight was appointed as trustee in straight to your inbox, sign up bankruptcy. to our mailing list here >>> | Page 1 Insolvency View February 2019 In March and May 2016, Mr Sleight disclaimed (2)(a) of the Insolvency Act 1986 as referring approximately 20 properties owned by Ms to a person who, at the time of the application, Mascall as onerous property.