The East Bolivian Andes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Summary

Environmental, Social, and Health Impact Assessment (ESHIA) for Vista Onshore Operations Executive Summary 24 June 2019 Project No.: 0510093 The business of sustainability Document details The details entered below are automatically shown on the cover and the main page footer. PLEASE NOTE: This table must NOT be removed from this document. Document title Environmental, Social, and Health Impact Assessment (ESHIA) for Vista Onshore Operations Document subtitle Executive Summary Project No. 0510093 Date 24 June 2019 Version 01 Author Luis Dingevan / Silvana Prado / Lisset Saenz Client Name Vista Oil & Gas Document history ERM approval to issue Version Revision Author Reviewed by Name Date Comments Draft 00 Luis Dingevan Natalia Alfrido 19/06/2019 Borrador a Vista / Silvana Delgado / Wagner Prado / Lisset Andrea Saenz Fernandez FInal 01 Luis Dingevan Natalia Alfrido 24/06/2019 / Silvana Delgado / Wagner Prado / Lisset Andrea Saenz Fernandez www.erm.com Version: 01 Project No.: 0510093 Client: Vista Oil & Gas 24 June 2019 Signature Page 24 June 2019 Environmental, Social, and Health Impact Assessment (ESHIA) for Vista Onshore Operations Executive Summary [Double click to insert signature] [Double click to insert signature] Alfrido Wagner Andrea Fernandez Sanday Partner in Charge Project Manager ERM Argentina S.A. Av. Cabildo 2677, Piso 6° (C1428AAI) Buenos Aires, Argentina © Copyright 2019 by ERM Worldwide Group Ltd and / or its affiliates (“ERM”). All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, without the prior written permission of ERM. www.erm.com Version: 01 Project No.: 0510093 Client: Vista Oil & Gas 24 June 2019 ENVIRONMENTAL, SOCIAL, AND HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESHIA) FOR VISTA ONSHORE OPERATIONS Executive Summary CONTENTS 1. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Argentine Repu,blic.,,-:, Biodiversit CosevaknPrjc Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized * Project -Document. Public Disclosure Authorized THE WORL.-DAINK GEF Documentation The Global Environment Facility (GEF) assistsdeveloping countries to protect the globalenvironment in four areas:global warming, pollution of internationalwaters-, destructionof biodiversity,and depletion of the ozone layer. The GEF is jointlyimplemented bytheUnited Nations Development Programme, the United Nations Environment Programme, andthe World Bank: GEF Project Documents - identifiedby a greenband - prpvideextended project- specific information.The implementing agency responsible for each.projectis identified by its logoon the coverof thedocument. GjobalEnvironment-Division EnvironmentDepartment . World-Bank 1818 H Street,NW Washington,DC 20433 Telephone:(202) 473-1816 Fax:(202) 522-3256 Report No. 17023-AR Argentine Republic Biodiversity Conservation Project ProjectDocument September 1997 Country Management Unit Argentina, Chile and Uruguay Latin America and the Caribbean Region CURRENCY EOUIVALENTS Currency Unit - Peso (Arg$) EXCHANGE RATE (September 16, 1997) US$1.00 Arg$1.00 Arg$1.00 = US$1.00 FISCALYEAR January 1 to December 31 WEIGHTS AND MEASURES The metric system has been used throughout the memorandum. Vice President: Mr. Shahid Javed Burki Director: Ms. Myma Alexander Acting Sector Leader: Mr. Luis Coirolo Team Leader: Mr. Robert Kirmse This report is basedon an AppraisalMission carried out in July 1997. -

A Spatial Analysis Approach to the Global Delineation of Dryland Areas of Relevance to the CBD Programme of Work on Dry and Subhumid Lands

A spatial analysis approach to the global delineation of dryland areas of relevance to the CBD Programme of Work on Dry and Subhumid Lands Prepared by Levke Sörensen at the UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre Cambridge, UK January 2007 This report was prepared at the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC). The lead author is Levke Sörensen, scholar of the Carlo Schmid Programme of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). Acknowledgements This report benefited from major support from Peter Herkenrath, Lera Miles and Corinna Ravilious. UNEP-WCMC is also grateful for the contributions of and discussions with Jaime Webbe, Programme Officer, Dry and Subhumid Lands, at the CBD Secretariat. Disclaimer The contents of the map presented here do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP-WCMC or contributory organizations. The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP-WCMC or contributory organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. 3 Table of contents Acknowledgements............................................................................................3 Disclaimer ...........................................................................................................3 List of tables, annexes and maps .....................................................................5 Abbreviations -

First Density Estimation of Two Sympatric Small Cats, Leopardus Colocolo and Leopardus Geoffroyi, in a Shrubland Area of Central Argentina

Ann. Zool. Fennici 49: 181–191 ISSN 0003-455X (print), ISSN 1797-2450 (online) Helsinki 29 June 2012 © Finnish Zoological and Botanical Publishing Board 2012 First density estimation of two sympatric small cats, Leopardus colocolo and Leopardus geoffroyi, in a shrubland area of central Argentina Nicolás Caruso1,2,*, Claudia Manfredi1, Estela M. Luengos Vidal1, Emma B. Casanaveo1,2 & Mauro Lucherinio1,2 1) GECM, Cat. Fisiología Animal, Depto. Biología, Bioquímica y Farmacia — UNS, San Juan 670, 8000 Bahía Blanca, Argentina (*corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected]) 2) Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Av. Rivadavia 1917, C1033AAJ, Capital Federal, Argentina Received 5 Aug. 2011, final version received 16 Jan. 2012, accepted 17 Jan. 2012 Caruso, N., Manfredi, C., Luengos Vidal, E. M., Casanave, E. B. & Lucherini, M. 2012: First den- sity estimation of two sympatric small cats, Leopardus colocolo and Leopardus geoffroyi, in a shrubland area of central Argentina. — Ann. Zool. Fennici 49: 181–191. Geoffroy’s and Pampas cats are small felids with large distribution ranges in South America. A camera trap survey was conducted in the Espinal of central Argentina to estimate abundance based on capture–recapture data. For density estimations we used both non-spatial methods and spatially explicit capture–recapture models (SECR). For Geoffroy’s cat we also obtained density estimates from 8 radio-tracked individuals. Based on the data on 10 Geoffroy’s cats and 7 Pampas cats, non-spatial methods pro- duced density ranges of 16.21–21.94 indiv./100 km2 and 11.34–17.58 indiv./100 km2, respectively. -

Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF)

GCF FP ARG ANNEX 3 Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Annex to the Funding Proposal Argentina REDD-plus RBP for results period 2014-2016 within the framework of the GCF Pilot Programme for REDD+ Results-based Payments 01 October 2020 | 1 Argentina REDD-plus RBP for results period 2014-2016 Funding Proposal Annex 2: ESMF Report Contents TABLES ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................................... 4 ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................... 8 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 9 2 CONTEXT - NATIVE FORESTS IN ARGENTINA ......................................................................................... 10 2.1 NATIVE FOREST COVER AND PRESSURES ON NATIVE FORESTS ................................................................................ 10 2.2 LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE CONTEXT ............................................................................................................ -

Ecology and Conservation of Four Sympatric Cat Species in the Argentinean Monte

Cat Project of the Month – June 2007 The IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group's website (www.catsg.org) presents each month a different cat conservation project. Members of the Cat Specialist Group are encouraged to submit a short description of interesting projects Ecology and Conservation of Four Sympatric Cat Species in the Argentinean Monte This project is aiming to contribute to the conservation of a unique and very little understood cat guild that occurs in a threatened landscape of Argentina, through the understanding of species-specific ecological requirements and interspecific interactions as well as awareness raising activities. Mauro Lucherini is a PhD Zoologist (Universitá di Siena, Italy) and he is GECM Field Coordinator (Universidad Nacional del Sur–UNS and CONICET). He is also leading a conservation biology project on the Andean mountain cats since 1998. Mauro has been a member of the Cat SG since 1998. Claudia Manfredi is a PhD Biologist at UNS; she has worked with Geoffroy’s cats since 1999. Claudia is a member of the Cat SG since 2005. [email protected]; [email protected] submitted: 1 June 2007 C. Manfredi and M. Lucherini with a live-captured Geoffroy’s Camera trap photo of a Pampas cat, Los Alamos Farm, cat (Photo GECM, UNS) Argentina (Photo GECM, UNS) The Pampas cat, Oncifelis colocolo, ranges from southern Ecuador and Peru to central, western, and southern Brazil, parts of Bolivia, central Chile, Paraguay Uruguay and southern Argentina (Sunquist and Sunquist, 2002). It has been recently up-graded to the Near Threatened IUCN category (Nowell, 2002). The Geoffroy’s cat, Oncifelis geoffroyi, is distributed from southern Bolivia and Brazil to the southern part of Patagonia in Chile and Argentina (Sunquist and Sunquist 2002). -

Updating the Distribution and Population Status of Jaguarundi, Puma Yagouaroundi (É

13 4 75–79 Date 2017 NOTES ON GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION Check List 13(4): 75–79 https://doi.org/10.15560/13.4.75 Updating the distribution and population status of Jaguarundi, Puma yagouaroundi (É. Geoffroy, 1803) (Mammalia: Carnivora: Felidae), in the southernmost part of its distribution range E. Luengos Vidal,1, 2 M. Guerisoli,1, 3 N. Caruso,1, 3 M. Lucherini1, 3 1 GECM (Grupo de Ecología Comportamental de Mamíferos), Lab. Fisiología Animal, Depto. Biología, Bioquímica y Farmacia, Universidad Nacional del Sur, San Juan 670, 8000 Bahía Blanca, Argentina. 2 INBIOSUR (Instituto de Ciencias Biológicas y Biomédicas del Sur), CONICET – UNS (Universidad Nacional del Sur), Bahía Blanca, Argentina. 3 CONICET (Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas), Buenos Aires, Argentina Corresponding author: Luengos Vidal E., [email protected] Abstract We report new occurrence records of Puma yagouaroundi (É. Geoffroy, 1803), a widely distributed but little known Neotropical carnivore, obtained over the last 10 years in Buenos Aires province, central Argentina. The records were collected by camera trapping surveys (n = 384 stations) and 195 interviews with local inhabitants. Our results improve our understanding of this species’ geographic range, especially its southernmost limit, and abundance, and confirm the need for more detailed studies to better assess the conservation status of this species in central Argentina and other parts of its range. Key words Argentine Espinal; carnivores; abundance; camera trapping; interviews. Academic editor: Guilherme S. T. Garbino | Received 15 December 2016 | Accepted 29 March 2017 | Published 11 July 2017 Citation: Luengos Vidal E, Guerisoli M, Caruso N, Lucherini M (2017) Updating the distribution and population status of Jaguarundi, Puma yagouaroundi (É. -

Environmental & Social Baseline

Environmental, Social, and Health Impact Assessment (ESHIA) for Vista Onshore Operations Environmental and Social Baseline 24 June 2019 Project No.: 0510093 The business of sustainability Document details The details entered below are automatically shown on the cover and the main page footer. PLEASE NOTE: This table must NOT be removed from this document. Document title Environmental, Social, and Health Impact Assessment (ESHIA) for Vista Onshore Operations Document subtitle Environmental and Social Baseline Project No. 0510093 Date 24 June 2019 Version 05 Author Silvana Prado / Rebeca Palomares / Lisset Saenz Client Name Vista Oil & Gas Document history ERM approval to issue Version Revision Author Reviewed by Name Date Comments Draft 00 Silvana Prado Andrea Alfrido 07/06/2019 Borrador a Vista / Rebeca Fernandez Wagner Palomares / Lisset Saenz Draft 01 Silvana Prado Andrea Alfrido 14/06/2019 Borrador a Vista / Rebeca Fernandez Wagner Palomares / Lisset Saenz Draft 02 Silvana Prado Andrea Alfrido 18/06/2019 Borrador a Vista / Rebeca Fernandez 7 Wagner Palomares / Natalia Lisset Saenz Delgado Draft 03 Silvana Prado Andrea Alfrido 18/06/2019 Borrador a Vista / Rebeca Fernandez / Wagner Palomares / Natalia Lisset Saenz Delgado Final 05 Silvana Prado Andrea Alfrido 24/06/19 / Natalia Fernandez Wagner Delgado www.erm.com Version: 05 Project No.: 0510093 Client: Vista Oil & Gas 24 June 2019 Signature Page 24 June 2019 Environmental, Social, and Health Impact Assessment (ESHIA) for Vista Onshore Operations Environmental and Social Baseline [Double click to insert signature] [Double click to insert signature] Alfrido Wagner Andrea Fernandez Sanday Partner in Charge Project Manager ERM Argentina S.A. Av. Cabildo 2677, Piso 6° (C1428AAI) Buenos Aires, Argentina © Copyright 2019 by ERM Worldwide Group Ltd and / or its affiliates (“ERM”). -

Patagonian Steppe

Patagonian Steppe 1. Geography and Climate a. Geographic location i. The Patagonian Steppe covers 188,000 square miles at the southern tip of South America, primarily in Argentina with a small area in Chile. It spans from the eastern foothills of the Andes to the Atlantic Ocean, from the Monte desert to the north to Tierra del Fuego at the southern tip of the continent. ii. This region is latitudinally equivalent to Washington state and Oregon. b. Topography i. The steppe topography features vast plains, rocky foothills, grassy stepped plateaus, river valleys and canyons. ii. Marked by seasonal lakes and streams. iii. The tableland region rises to an altitude of 5,000 feet. c. Climate i. The Patagonian Steppe is in the rain-shadow of the Andes, the climate is very dry and cold. ii. Two climatic zones: 1. northern, semi-arid zone. mean annual temperature between 53o and 68° F, and annual rainfall between 3.5 to 17 inches. 2. southern zone, cold, dry climate (desert). mean annual o temperature ranging between 39 and 55° F, and annual precipitation, including snow and rain, ranges between 5 and 8 inches. iii. Cold desert. Highest temperature is 68° F, rarely exceeds 53 °F, and averages just 37 °F. iv. Essentially two seasons, summer and winter, with spring and fall only occurring as brief transitions. Winter generally lasts for five months from late April to mid September. v. Frost and snow can occur at almost any time of year. vi. Precipitation is scarce, ranging from 4 to 12 inches per year, concentrated on the coldest months, from April to September. -

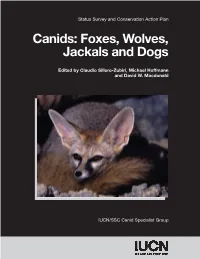

Canids: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan

IUCN/Species Survival Commission Foxes, Wolves, Jackals and Dogs Canids: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is one of six volunteer commissions of IUCN – The World Conservation Union, a union of sovereign states, government agencies and non- governmental organisations. IUCN has three basic conservation objectives: to secure the conservation of nature, and especially of biological diversity, as an essential foundation for the future; to ensure that where the Earth’s natural resources are used this is done in a wise, Canids: Foxes, Wolves, equitable and sustainable way; and to guide the development of human communities towards ways of life that are both of good quality and in enduring harmony with other components of the biosphere. Jackals and Dogs A volunteer network comprised of some 8,000 scientists, field researchers, government officials and conservation leaders from nearly every country of the world, the SSC membership is an unmatched source of information about biological diversity and its conservation. As such, SSC Edited by Claudio Sillero-Zubiri, Michael Hoffmann members provide technical and scientific counsel for conservation projects throughout the world and serve as resources to governments, international conventions and conservation and David W. Macdonald organisations. IUCN/SSC Action Plans assess the conservation status of species and their habitats, and specifies conservation priorities. The series is one of the world’s most authoritative sources of Survey and Conservation Action -

Short Communication How Effective Is the MERCOSUR's Network Of

Oryx Vol 40 No 1 January 2005 Short Communication How effective is the MERCOSUR’s network of protected areas in representing South America’s ecoregions? Alvaro Soutullo and Eduardo Gudynas Abstract We evaluate the effectiveness of the using a regional approach. This is of particular relevance MERCOSUR’s network of protected areas in representing for the cost-efficient protection of the 20 ecoregions that South America’s ecoregions. The region contains 1,219 are shared by two or more countries. While only c. 20 % non-overlapping protected areas covering nearly of the ecoregions found in Brazil are shared with other 2,000,000 km2. Fifty percent of the reserves are <100 km2 countries, >75% of the ecoregions in Bolivia, c. 70% in and 75% <1,000 km2. Less than a half of the 75 ecoregions Argentina, >60% in Chile, and all the ecoregions in Para- in the MERCOSUR have at least 10% of their area within guay and Uruguay, are shared with other countries. protected areas, and only 13 when just reserves in IUCN Overall, although it currently covers 14% of the region, categories I–IV are considered. In general, forests are the network of protected areas of the MERCOSUR still better represented than other biomes. At the national performs poorly in protecting its ecoregions. level the network of protected areas in Uruguay is the Keywords least developed in the region, with those of Bolivia and Continental conservation, ecoregions, effec- Chile the most developed. For 10% of each ecoregion to be tiveness, GAP analysis, MERCOSUR, representation, reserves, South America. protected at least another 500,000 km2 would have to be incorporated into the network. -

Journal of Zoology

Journal of Zoology Journal of Zoology. Print ISSN 0952-8369 Evaluating a potentially strong trophic interaction: pumas and wild camelids in protected areas of Argentina E. Donadio1, A. J. Novaro2, S. W. Buskirk1, A. Wurstten2, M. S. Vitali3 & M. J. Monteverde4 1 Program in Ecology and Department of Zoology & Physiology, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY, USA 2 INIBIOMA-CONICET and Wildlife Conservation Society-Patagonian and Andean Steppe Program, Neuque´n, Argentina 3 Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Buenos Aires, Argentina 4 Departamento de Fauna Terrestre, Centro de Ecolog´ıa Aplicada del Neuque´n, Neuque´ n, Argentina Keywords Abstract puma; guanaco; vicuna;˜ predation; South America. Predatory interactions involving large carnivores and their ungulate prey are increasingly recognized as important in structuring terrestrial communities, but Correspondence such interactions have seldom been studied in the temperate Neotropics. Here, the Emiliano Donadio, Program in Ecology and large carnivore guild is limited to a single species, the puma Puma concolor, native Department of Zoology & Physiology, prey populations have been drastically reduced and lagomorphs and ungulates University of Wyoming, Laramie 82072, have been introduced. We examined puma dietary patterns under varying abun- WY, USA. Tel: +1 307 766 5299; dances of native camelid prey – guanacos and vicunas˜ – in protected areas of Fax: +1 307 766 5625 northwestern Argentina. We collected puma feces from seven protected areas, and Email: [email protected] sampled each area for the relative abundance of camelids using on-foot strip and vehicle transects. In one area, where longitudinal studies have been conducted, we Editor: Andrew Kitchener examined the remains of vicunas˜ and guanacos for evidence of puma predation in 2004–2006.