The Dissertation Committee for Rennison P. Lalgee Certifies That This Is the Approved Version of the Following Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chart Book Template

Real Chart Page 1 become a problem, since each track can sometimes be released as a separate download. CHART LOG - F However if it is known that a track is being released on 'hard copy' as a AA side, then the tracks will be grouped as one, or as soon as known. Symbol Explanations s j For the above reasons many remixed songs are listed as re-entries, however if the title is Top Ten Hit Number One hit. altered to reflect the remix it will be listed as would a new song by the act. This does not apply ± Indicates that the record probably sold more than 250K. Only used on unsorted charts. to records still in the chart and the sales of the mix would be added to the track in the chart. Unsorted chart hits will have no position, but if they are black in colour than the record made the Real Chart. Green coloured records might not This may push singles back up the chart or keep them around for longer, nevertheless the have made the Real Chart. The same applies to the red coulered hits, these are known to have made the USA charts, so could have been chart is a sales chart and NOT a popularity chart on people’s favourite songs or acts. Due to released in the UK, or imported here. encryption decoding errors some artists/titles may be spelt wrong, I apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. The chart statistics were compiled only from sales of SINGLES each week. Not only that but Date of Entry every single sale no matter where it occurred! Format rules, used by other charts, where unnecessary and therefore ignored, so you will see EP’s that charted and other strange The Charts were produced on a Sunday and the sales were from the previous seven days, with records selling more than other charts. -

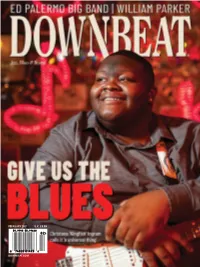

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Five Star with Every Heartbeat Mp3, Flac, Wma

Five Star With Every Heartbeat mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Funk / Soul Album: With Every Heartbeat Country: UK Released: 1989 Style: Synth-pop, Funk MP3 version RAR size: 1585 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1701 mb WMA version RAR size: 1591 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 694 Other Formats: MMF MP3 VOC AUD APE AU XM Tracklist Hide Credits With Every Heartbeat A Producer, Arranged By, Mixed By, Written-By – Wayne Brathwaite Sound Sweet B Producer – Buster PearsonProducer, Written-By – Delroy Pearson, Doris Pearson Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – BMG Records (UK) Ltd. Copyright (c) – BMG Records (UK) Ltd. Record Company – Bertelsmann Music Group Distributed By – BMG Records Distributed By – BMG Ariola Distributed By – RCA Ltd. Marketed By – RCA Ltd. Published By – Zomba Music Publishers Ltd. Published By – Tent Music Ltd. Published By – Chrysalis Music Ltd. Pressed By – CBS Pressing Plant, Aston Clinton Mastered At – Utopia Studios Credits Design – The Leisure Process Mastered By – MS.* Notes ℗ © 1989 BMG Records (UK) Limited Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Printed): 5 012394 269371 Barcode (Scanned): 5012394269371 Matrix / Runout (Runout etched side A): PB - 42693 - A - 1 ƱTOPIA.MS. Λ Matrix / Runout (Runout etched side B): PB - 42693 - B - 1 `1 ƱTOPIA.MS. Λ Matrix / Runout (Label side A): PB 42693 A‡ Matrix / Runout (Label side B): PB 42693 B‡ Label Code: LC 0316 Other (Distribution code Germany): AC Other (Distribution code France): RC110 Other (Distribution code U.K.): AA Other versions Category -

Anthology of Moontigerntn Anthology of Moontigerntn

Anthology of moontigerntn Anthology of moontigerntn About the author Bo Lanier is from Chattanooga, Tennessee and has become an established poet with five books to his credit that were published in Canada. He received several achievement awards in creative writing through poetry.com and has recently published two eBooks and one paperback book through Lulu.com. After a nine year hiatus, Bo returned to publishing his poems with a new outlook and fresh ideas. His other talents include singing and songwriting. Page 2/356 Anthology of moontigerntn summary A New Beginning If I Had Wings Willow Trying To Hide a Fire in the Dark God Gave Me You Nights Like These I Vow Here and Now Dead Tree Garden Tell Me Little Miss Perfect Get the Hell Out Of My Dreams Kiev Come Live With Me Nothing Is Set In Stone Leave Me Alone Thor His Loss Walking Out the Door Firebird Mother and Child You\'re Crazy Hills of Snow Wishing On Stars Page 3/356 Anthology of moontigerntn Staring Down Desire Love is Forever I Have To Know Prophecy of Pisces (Dream of Water) They Cannot Stand Between Us Lilith Hawaiian Love Story Pure Love If Not For You I Am Who I Am and It Is What It Is Me and My Baby Still Waiting Every Time I\'m Around You Come Monday One Rose Paybacks Are Hell Nightstorm I Love an Alien Going For the Gold As In a Dream Burn Out the Night In the Year of the Clover Hanging on a Honey Suckle Vine Be Somebody?s Angel Full Moon over Werewolf Page 4/356 Anthology of moontigerntn Rock 84001 Like The Dickens Patriarch of My Heart Hot-blooded Aries It Must Be Jesus -

The Mississippi Mass Choir

R & B BARGAIN CORNER Bobby “Blue” Bland “Blues You Can Use” CD MCD7444 Get Your Money Where You Spend Your Time/Spending My Life With You/Our First Feelin's/ 24 Hours A Day/I've Got A Problem/Let's Part As Friends/For The Last Time/There's No Easy Way To Say Goodbye James Brown "Golden Hits" CD M6104 Hot Pants/I Got the Feelin'/It's a Man's Man's Man's World/Cold Sweat/I Can't Stand It/Papa's Got A Brand New Bag/Feel Good/Get on the Good Foot/Get Up Offa That Thing/Give It Up or Turn it a Loose Willie Clayton “Gifted” CD MCD7529 Beautiful/Boom,Boom, Boom/Can I Change My Mind/When I Think About Cheating/A LittleBit More/My Lover My Friend/Running Out of Lies/She’s Holding Back/Missing You/Sweet Lady/ Dreams/My Miss America/Trust (featuring Shirley Brown) Dramatics "If You come Back To Me" CD VL3414 Maddy/If You Come Back To Me/Seduction/Scarborough Faire/Lady In Red/For Reality's Sake/Hello Love/ We Haven't Got There Yet/Maddy(revisited) Eddie Floyd "Eddie Loves You So" CD STAX3079 'Til My Back Ain't Got No Bone/Since You Been Gone/Close To You/I Don't Want To Be With Nobody But You/You Don't Know What You Mean To Me/I Will Always Have Faith In You/Head To Toe/Never Get Enough of Your Love/You're So Fine/Consider Me Z. Z. -

Title Edit T Series RH RD RB RK BPM PT Track Track Aritist First

Aritist First Title Edit PT Track T Series Track RH RD RB RK BPM 1 GIANT LEAP MY CULTURE Radio Edit T657 10 094 1 PLUS 1 CHERRY BOMB T552 11 128 1000 CLOWNS (NOT THE) GREATEST RAPPER T470 13 096 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT PT114 10 112 YOUR LETTER Radio Mix T491 08 070 112 IT'S OVER NOW Radio Edit T563 09 098 112 PEACHES & CREAM Radio Mix T585 14 6612 103 112 DANCE WITH ME Radio Mix T604 10 102 112 (f/ Lil' Z) ANYWHERE (Radio Mix) T465 12 063 112 f/ MA$E LOVE ME (Radio Mix) T454 11 090 12 STONES BROKEN Radio Version #1 No Vocal 2809 097 12 STONES THE WAY I FEEL 3215 078 12 VOLT SEX HOOK IT UP T557 14 143 1910 FRUITGUM FACTORY SIMON SAYS PT114 9 1NC COULD'VE BEEN ME 098 2 IN A ROOM WIGGLE IT PT36 9 2 LIVE CREW ME SO HORNY (X-RATED) PT22 8 2 LIVE CREW WE WANT SOME PUSSY (X-RATED) PT39 7 2 PAC FEATURING OUTLAWZ VOICES CARRY PT116 3 2 SKINNEE J'S GROW UP Radio Edit T638 09 120 2 UNLIMITED TWILIGHT ZONE (RAVE EDIT) PT36 8 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMITS PT40 9 2 UNLIMITED GET READY FOR THIS (ORCHESTRAL MIX) PT54 3 20 FINGERS FEATURING SHORT DICK MAN PT87 17 2GE+HERGILLETTE U+ME=US (CALCULUS) T529 13 079 2GE+HER THE HARDEST PART OF BREAKING UP (US T553 15 112 2ND II NONE f/ AMG & DJ QUIK UPGETTING 'N DA CLUB BACK Y Radio Mix T498 11 095 2PAC I WONDER IF HEAVEN GOT A GHETTO (Soulpower Hip Hop Radio T408 13 108 2PAC CHANGES (Radio Edit) T459 10 111 2PAC THUG NATURE Radio Edit 2006 096 2PAC UNTIL THE END OF TIME Clean Radio Edit T581 08 097 2PAC LETTER 2 MY UNBORN 2404 108 2PAC THUGZ MANSION Radio Edit Clean T667 11 089 2PAC f/ NAS THUGZ MANSION Acoustic -

New Mum E Juij J, D1):3

New Mum e Juij j, D1):3 •••••. It ti, Ht \b ,1, ,(1 •• ••••••• 0••••••••••• , •••••••••ibie •gbe•ir •••eu ••11•Clv••111. ••••••••••1 ••••.•••641 Cbeloo ,)ocoeet ALANIS MORISSETTE RAVIKIRANMAHAL/BHATT FUGAZ! FEMI KUTI Rules: Just put something in this bed! You can draw, paste, decoupage, or otherwise construct something to fill in the space. Feel free to use Gene a facsimile of this page. You can make your entry as filthy as you like, but we are a pretty classy "Sleep Well Tonight" contest organization, so your entry probably won't win unless it's a particularly brilliant execution. The hr winners will be chosen based on several factors, including originality, FILL IN THE BED! creativity, uniqueness, ingenuity and appeal. The decision of our judges is final. And, no, they cannot be bought. "Sleep Well Tonight" contest prizes First prize: A weekend for two (air transportation and 2 nights hotel) in the city of your choice (within the continental U.S.), and a Gene flight jacket (approximate value: $1,000) 5 Second prizes: A comfy pillow and a Gene flight jacket (approximate value: $75) 10 Third prizes: A sleep mask and an autographed copy of the Gene Olympian vinyl (approximate value: $20) Send entries to: "Sleep Well Tonight" contest c/o Scott Carter 1416 N. La Brea Ave. Hollywood CA 90028 Enter as many times as you want, but only one entry per envelope, please. No purchase necessary to enter Sponsored by PolyGram Records, Inc To enter by wrifing. send a postcard lo PolydonAllas Records, 1416 N. La Brea Ave Hollywood, CA 90028. -

Artist Or Group Song Album Title Braydon Alex Alex Braydon Strait

Song Artist or Group Album Title (Dance Mix Radio Braydon Alex Alex Braydon Strait George One Step At A Time 0 Matchbox 20 #1 Crush Garbage Romeo & Juliet - Soundtra 1-2-3 Barry Len Billboard's Top Rock ‘N’ Roll Hits - 1965 100% Pure Love Waters Crystal Mobile Beat Disc 2 100% Pure Love Waters Crystal Pop Hot Hits Vol. 14 100 Ways Porno For Pyros Good God's Urge 100 Years From Now Huey Lewis And The News 1001 Nights Waltz Strauss II Johann Waltzes By Strauss & Ziehrer 1,2,3,4 (Sumpin' New) (Timber Clean R Coolio 16 Candles Crests The Billboard's Top Rock ‘N’ Roll Hits - 1959 18 Til I Die (Single Mix) Adams Bryan 18 Til I Die 1969 Stegall Keith Passages 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 1999 (Edit) Prince 1999 1St Of The Month (Radio Edit) Bone Thugs-n-harmony 2 Become 1 Spice Girls Spice Girls 2 Wicky (Radio Edit) Hooverphonic A New Stereophonic Sound 21st Century (Digital Boy) Bad Religion Pop Hot Hits Vol. 18 26 Cents Wilkinsons Nothing But Love 29 Nights Leigh Danni 29 Nights 3 AM Eternal (Live At The SSL KLF The Club MTV Party To Go Vol. 2 30 Days In The Hole Humble Pie Harley Davidson - Road Songs (Disc 1) 32 Flavors Davis Alana Blame It On Me 4 Page Letter (Timbaland's Main Aaliyah One In A Million 4 Seasons Of Loneliness (Radio Edit) Boyz Ii Men Evolution 4 To 1 In Atlanta Byrd Tracy 40 Days And 40 Nights McGraw Tim Not A Moment Too Soon 455 Rocket (Radio Edit) Mattea Kathy Love Travels 5 Miles To Empty (Radio Edit) Brownstone Still Climbing 5 O'clock (Radio Edit) Nonchalant 5 Steps (Radio Edit) Dru Hill Dru Hill 5-4-3-2 (Yo! Time Is Up) Jade Pop Hot Hits Vol. -

Cash Box's Gospel Editor, Gregory S

MAGAZINE TRADE COIN-OP THE February 8, 1992 Newspaper $3.50 ) ) VOL. LV, NO. 24, FEBRUARY 8, 1992 STAFF BOX GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher KEITH ALBERT Vice President/General Manager FRED L. GOODMAN Editor In Chiel CAMILLE COMPASIO Director, Coin Machine Operations LEE JESKE New York Editor Marketing LEON BELL (L A ) MARK WAGNER (Nash ) Editorial DANDY CLARK, Assoc. Ed (LA) BRYAN DeVANEY, Assoc. Ed (LA) BERNETTA GREEN (N Y.) INSIDE THE BOX WILMA MELTON (Nash STEVE GIUFFRIDA (Nash) CORY CHESHIRE (Nash) COVER STORY GREGORY S. COOPER-Gospel (Nash.) Chart Research Bobby Jones: Exploding On The CHERRY URESTI (LA) JIMMY PASCHAL (LA) Gospel Scene TONIE HECTOR (LA TODD MURPHY (L A) Dr. Bobby Jones, already closing in on the title of the new reigning RAYMOND BALLARD (LA) king of gospel, presents his latest Gospel Explosion V, which will take JOHN COSSIBOOM (Nash.) place February 5-8 at the Tennessee Performing Arts Center Polk Theater in Nashville. Over 2,500 people are expected to attend the Production JIM GONZALEZ event which features workshops, concerts, awards show and a fan Art Director fair. Cash Box's gospel editor, Gregory S. Cooper, writes about Jones and the Explosion. Circulation NINATREGUI3, Manager — see page 10 CYNTHIA BANTA Publication Offices NEWS NEW YORK 157 W. 57th Street (Suite 503) C+C Music Factory Sweeps AMA’s New York, NY 10019 Phone: (21 2) 586-2640 C+C Music Factory, Columbia Records' rookie dance/pop act, Fax: (212) 582-2571 took home five American Music Awards this week, besting many HOLLYWOOD record biz veterans and setting the stage for possible Grammy vic- 6464 Sunset Blvd (Suite 605) Hollywood, C A 90028 tories. -

Video: the Who and the "What?

VOL. LVIII, NO. 2 Newspaper $3.95 Spin Doctors' House Call/ Jackson Browne Still Alive Video: The Who And The "What? Adi Chet Atkins VOL. LVSI1, NO. 1 September 10, 1994 STAFF GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher KEITH ALBERT Exec. V.PJGeneral Manager MARK WAGNER Director, Nashville Operations RICH NIECIECKI Managng Edtor EDITORIAL Los Angeles MICHAEL MARTINEZ JOHN GOFF STEVE BALTIN Nashville RICHARD McVEY INSIDE THE BOX GARY KEPLINGER New York TED WILLIAMS CHART RESEARCH Los Angeles COVER STORY DANI FRIEDMAN NICOLA RAE RONCO BRIAN PARMELLY AARON SPERSKE ANGIE LA1ACONA Nadiville Chet Atkins Gets Some Licks In GARY KEPLINGER MARKETING/ADVERTISING Chet Atkins has been around a long time, but this ol’ dog can learn new New York STAN LEWIS tricks... or licks, as the case may be with his latest (75th or so) release Read Los Angeles MATTHEW SAVALAS Licks which is highlighted in an upcoming special. Cash My (Columbia), TNN MAXIAL. BANE Box talked with the living legend as he was about to be honored yet again, DAWN HARRIS CIRCULATION this time by NARAS. NINA TREGUB, Manager PASHA SANTOSO —see pages 16 & 17 PRODUCTION SHARON CHAMBLISS -TRAYLOR Talent Reviews PUBLICATION OFFICES NEW YORK Epic’s Spin Doctors made a house call to Irvine Meadows Amphitheatre in 345 W 581h Street Sute 15W New York, NY 10019 Southern California late last month, only to be followed the next night by Phone: (212) 245-4224 singer-songwriter extraordinaire Jackson Browne, touring in support of I'm Alive (Elektra)...AND STEVE Fax: (212) 245-4228 BALTIN WAS THERE. HOLLYWOOD 6464 Srnset Blvd (Sute 605) —see page 5 Hollywood, CA 90028 Phone (213) 464-8241 Fax: (213)464-3235 Video Reviews NASHVILLE 50 Muse Square Wtest (Sute 804) The Who and the “What?” (the performer formerly known as “Prince”) are both captured on home video Nashville, TN 37203-3212 Phone: (615) 329-2898 currently available.