Tax and Transfer Research Group, Berlin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tax Appeals Rules Procedures

Tax Appeals Tribunal Rules & Procedures The rules of the game February 2017 Glossary of terms KRA Kenya Revenue Authority TAT Tax Appeals Tribunal TATA Tax Appeals Tribunal Act TPA Tax Procedures Act VAT Value Added Tax 2 © Deloitte & Touche 2017 Definition of terms Tax decision means: a) An assessment; Tax law means: b) A determination of tax payable made to a a) The Tax Procedures Act; trustee-in-bankruptcy, receiver, or b) The Income Tax Act, Value Added liquidator; Tax Act, and Excise Duty Act; and c) A determination of the amount that a tax c) Any Regulations or other subsidiary representative, appointed person, legislation made under the Tax director or controlling member is liable Procedures Act or the Income Tax for under specified sections in the TPA; Act, Value Added Tax Act, and Excise d) A decision on an application by a Duty Act. taxpayer to amend their self-assessment return; Objection decision means: e) A refund decision; f) A decision requiring repayment of a The Commissioner’s decision either to refund; or allow an objection in whole or in part, or g) A demand for a penalty. disallow it. Appealable decision means: a) An objection decision; and b) Any other decision made under a tax law but excludes– • A tax decision; or • A decision made in the course of making a tax decision. 3 © Deloitte & Touche 2017 Pre-objection process; management of KRA Audit KRA Audit Notes The TPA allows the Commissioner to issue to • The KRA Audits are a tax payer a default assessment, amended undertaken by different assessment or an advance assessment departments of the KRA that (Section 29 to 31 TPA). -

Taxation Paradigms: JOHN WEBB SUBMISSION APRIL 2009

Taxation Paradigms: What is the East Anglian Perception? JOHN WEBB A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy SUBMISSION APRIL 2009 BOURNEMOUTH UNIVERSITY What we calf t[ie beginningis oftenthe end And to makean endis to makea beginning ?fie endis wherewe start ++++++++++++++++++ Weshall not ceasefrom exploration And the of exploring end .. Wilt to arrivewhere we started +++++++++++++++++ 7.S f: Cwt(1974,208: 209) ? fie Four Quartets,Coffected Poems, 1909-1962 London: Faderand Fader 2 Acknowledgements The path of a part time PhD is long and at times painful and is only achievablewith the continued support of family, friends and colleagues. There is only one place to start and that is my immediate family; my wife, Libby, and daughter Amy, have shown incredible patienceover the last few years and deserve my earnest thanks and admiration for their fantastic support. It is far too easy to defer researchwhilst there is pressingand important targets to be met at work. My Dean of Faculty and Head of Department have shown consistent support and, in particular over the last year my workload has been managedto allow completion. Particularthanks are reservedfor the most patientand supportiveperson - my supervisor ProfessorPhilip Hardwick.I am sure I am one of many researcherswho would not have completed without Philip - thank you. ABSTRACT Ever since the Peasant'sRevolt in 1379, collection of our taxes has been unpopular. In particular when the taxes are viewed as unfair the population have reacted in significant and even violent ways. For example the Hearth Tax of 1662, Window Tax of 1747 and the Poll tax of the 1990's have experiencedpublic rejection of these levies. -

The Macroeconomics Effects of a Negative Income

The Macroeconomics e¤ects of a Negative Income Tax Martin Lopez-Daneri Department of Economics The University of Iowa February 17, 2010 Abstract I study a revenue neutral tax reform from the actual US Income Tax to a Negative Income Tax (N.I.T.) in a life-cycle economy with individual heterogeneity. I compare di¤erent transfers in a stationary equilibrium. I …nd that the optimal tax rate is 19.51% with a transfer of 11% of GDP per capita, roughly $5,172.79. The average welfare gain amounts to a 1.7% annual increase of individual consumption. All agents bene…t from the reform. There is a 17.52% increase in GDP per capita and a decrease of 13% in Capital per labor. Capital per Output declines 10.22%. 1 Introduction The actual US Income Tax has managed to become increasingly complex, because of its numerous tax credits, deductions, overlapping provisions and increasing marginal rates. The Income Tax introduces a considerable number of distortions in the economy. There have been several proposals to simplify it. However, this paper focuses on one of them: a Negative Income Tax (NIT). In this paper, I ask the following questions: What are the macroeconomic e¤ects of replacing the Income Tax with a Negative Income Tax? Speci…cally, is there any welfare gain from this Revenue-Neutral Reform? Particularly, I am considering a NIT that taxes all income at the same marginal rate and 1 makes a lump-sum transfer to all households. Not only does the tax proposed is simple but also all households have a minimum income assured. -

Transfer of Ownership Guidelines

Transfer of Ownership Guidelines PREPARED BY THE MICHIGAN STATE TAX COMMISSION Issued October 30, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Information 3 Transfer of Ownership Definitions 4 Deeds and Land Contracts 4 Trusts 5 Distributions Under Wills or By Courts 8 Leases 10 Ownership Changes of Legal Entities (Corporations, Partnerships, Limited Liability Companies, etc.) 11 Tenancies in Common 12 Cooperative Housing Corporations 13 Transfer of Ownership Exemptions 13 Spouses 14 Children and Other Relatives 15 Tenancies by the Entireties 18 Life Leases/Life Estates 19 Foreclosures and Forfeitures 23 Redemptions of Tax-Reverted Properties 24 Trusts 25 Court Orders 26 Joint Tenancies 27 Security Interests 33 Affiliated Groups 34 Normal Public Trades 35 Commonly Controlled Entities 35 Tax-Free Reorganizations 37 Qualified Agricultural Properties 38 Conservation Easements 41 Boy Scout, Girl Scout, Camp Fire Girls 4-H Clubs or Foundations, YMCA and YWCA 42 Property Transfer Affidavits 42 Partial Uncapping Situations 45 Delayed Uncappings 46 Background Information Why is a transfer of ownership significant with regard to property taxes? In accordance with the Michigan Constitution as amended by Michigan statutes, a transfer of ownership causes the taxable value of the transferred property to be uncapped in the calendar year following the year of the transfer of ownership. What is meant by “taxable value”? Taxable value is the value used to calculate the property taxes for a property. In general, the taxable value multiplied by the appropriate millage rate yields the property taxes for a property. What is meant by “taxable value uncapping”? Except for additions and losses to a property, annual increases in the property’s taxable value are limited to 1.05 or the inflation rate, whichever is less. -

The Cost of the Vote: Poll Taxes, Voter Identification Laws, and the Price of Democracy

File: Ellis final for Darby Created on: 4/9/2009 8:17:00 PM Last Printed: 5/19/2009 1:10:00 PM THE COST OF THE VOTE: POLL TAXES, VOTER IDENTIFICATION LAWS, AND THE PRICE OF DEMOCRACY ATIBA R. ELLIS† INTRODUCTION The election of Barack Obama as the forty-fourth President of the United States represents both the completion of a historical campaign season and a triumph of the Civil Rights revolution of the twentieth cen- tury. President Obama’s 2008 campaign, along with the campaigns of Senators Hillary Rodham Clinton and John McCain, was remarkable in both the identities of the politicians themselves1 and the attention they brought to the political process. In particular, Obama attracted voters from populations which have not been traditionally represented in na- tional politics. His run was hallmarked, in large part, by significant grassroots fundraising, a concerted effort to generate popular appeal, and, most important, massive voter turnout efforts.2 As a result, this election cycle generated significant increases in participation during the primary season.3 Turnout in the general election did not meet anticipated record † Legal Writing Instructor, Howard University School of Law. J.D., M.A., Duke Univer- sity, 2000. An early version of this paper was presented at the Writer’s Workshop of the Legal Writing Institute in summer 2007. Later versions were presented at the November 2007 Howard University School of Law faculty colloquy and the September 2008 Northeast People of Color Legal Scholarship Conference. I gratefully acknowledge Andrew Taslitz, Sherman Rogers, Derek Black, Paulette Caldwell, Phoebe Haddon, and Daniel Tokaji for their thoughtful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. -

Volume 3: Value-Added

re Volume 3 Value-Added Tax Office of- the Secretary Department of the Treasury November '1984 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume Three Page Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1 Chapter 2: THE NATURE OF THE VALUE-ADDED TAX I. Introduction TI. Alternative Forms of Tax A. Gross Product Type B. Income Type C. Consumption Type 111. Alternative Methods of Calculation: Subtraction, Credit, Addition 7 A. Subtraction Method 7 8. Credit Method 8 C. Addition Method 8 D. Analysis and Summary 10 IV. Border Tax Adjustments 11 V. Value-Added Tax versus Retail Sales Tax 13 VI. Summary 16 Chapter -3: EVALUATION OF A VALUE-ADDED TAX 17 I. Introduction 17 11. Economic Effects 17 A. Neutrality 17 B. saving 19 C. Equity 19 D. Prices 20 E. Balance of Trade 21 III. Political Concerns 23 A. Growth of Government 23 B. Impact on Income Tax 26 C. State-Local Tax Base 26 Iv. European Adoption and Experience 27 Chapter 4: ALTERNATIVE TYPES OF SALES TAXATION 29 I. Introduction 29 11. Analytic Framework 29 A. Consumption Neutrality 29 E. Production and Distribution Neutrality 30 111. Value-Added Tax 31 IV. Retail Sales Tax 31 V. Manufacturers and Other Pre-retail Taxes 33 VI. Personal Exemption Value-Added Tax 35 VII. Summary 38 iii Page Chapter 5: MAJOR DESIGN ISSUES 39 I. Introduction 39 11. Zero Rating versus Exemption 39 A. Commodities 39 B. Transactions 40 C. Firms 40 D. Consequences of zero Rating or Exemption 41 E. Tax Credit versus Subtraction Method 42 111. The Issue of Regressivity 43 A. Adjustment of Government Transfer Payments 43 B. -

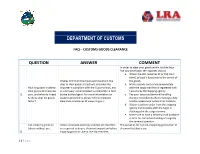

Department of Customs

DEPARTMENT OF CUSTOMS FAQ – CUSTOMS GOODS CLEARANCE QUESTION ANSWER COMMENT In order to clear your goods within the five hour – five day timeframe, the importer should: a. Obtain the CRF (whether DI or PSI) from BIVAC at least 5 days prior to the arrival of It takes minimum five hours and maximum five the goods. days to clear goods at Customs, provided the b. Make a goods declaration immediately How long does it take to importer is compliant with the Customs laws, and after the cargo manifest is registered with clear goods at a Customs all necessary documentation is completed in time Customs by the shipping agency. 1. port, and what do I need by the broker/agent. For more information on c. Pay your taxes and terminal handling to do to clear my goods customs procedures, please refer to Customs charges immediately after receiving a duty faster? clearance procedures at www.lra.gov.lr. and tax assessment notice from Customs. d. Obtain a delivery order from the shipping agency immediately after the cargo is discharged in the cargo terminal. e. Make sure to have a delivery truck available in time for immediate loading of cargo by the terminal operator. Can I ship my goods to Unless otherwise expressly exempt, all importers The penalties for not pre-inspecting goods prior to Liberia without pre- are required to do pre-shipment inspection before shipment to Liberia are: 2. shipping goods to Liberia. the Government, 1 | P a g e shipment inspection through Administrative Regulation No. 12. 14263 – a. 10% of CIF value for first and second (PSI)? 2/MOF/R/BCE/14 October 2013, requires offense penalties for failure to have goods pre-inspected. -

Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide

Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide 2021 Preface he Worldwide Estate and Inheritance trusts and foundations, settlements, Tax Guide 2021 (WEITG) is succession, statutory and forced heirship, published by the EY Private Client matrimonial regimes, testamentary Services network, which comprises documents and intestacy rules, and estate Tprofessionals from EY member tax treaty partners. The “Inheritance and firms. gift taxes at a glance” table on page 490 The 2021 edition summarizes the gift, highlights inheritance and gift taxes in all estate and inheritance tax systems 44 jurisdictions and territories. and describes wealth transfer planning For the reader’s reference, the names and considerations in 44 jurisdictions and symbols of the foreign currencies that are territories. It is relevant to the owners of mentioned in the guide are listed at the end family businesses and private companies, of the publication. managers of private capital enterprises, This publication should not be regarded executives of multinational companies and as offering a complete explanation of the other entrepreneurial and internationally tax matters referred to and is subject to mobile high-net-worth individuals. changes in the law and other applicable The content is based on information current rules. Local publications of a more detailed as of February 2021, unless otherwise nature are frequently available. Readers indicated in the text of the chapter. are advised to consult their local EY professionals for further information. Tax information The WEITG is published alongside three The chapters in the WEITG provide companion guides on broad-based taxes: information on the taxation of the the Worldwide Corporate Tax Guide, the accumulation and transfer of wealth (e.g., Worldwide Personal Tax and Immigration by gift, trust, bequest or inheritance) in Guide and the Worldwide VAT, GST and each jurisdiction, including sections on Sales Tax Guide. -

The African-American Church, Political Activity, and Tax Exemption

JAMES_EIC 1/11/2007 9:47:35 PM The African-American Church, Political Activity, and Tax Exemption Vaughn E. James∗ ABSTRACT Ever since its inception during slavery, the African-American Church has served as an advocate for the socio-economic improve- ment of this nation’s African-Americans. Accordingly, for many years, the Church has been politically active, serving as the nurturing ground for several African-American politicians. Indeed, many of the country’s early African-American legislators were themselves mem- bers of the clergy of the various denominations that constituted the African-American Church. In 1934, Congress amended the Internal Revenue Code to pro- hibit tax-exempt entities—including churches and other houses of worship—from allowing lobbying to constitute a “substantial part” of their activities. In 1954, Congress further amended the Code to place an absolute prohibition on political campaigning by these tax-exempt organizations. While these amendments did not specifically target churches and other houses of worship, they have had a chilling effect on efforts by these entities to fulfill their mission. This chilling effect is felt most acutely by the African-American Church, a church estab- lished to preach the Gospel and engage in activities which would im- prove socio-economic conditions for the nation’s African-Americans. This Article discusses the efforts made by the African-American Church to remain faithful to its mission and the inadvertent attempts ∗ Professor of Law, Texas Tech University School of Law. The author wishes to thank Associate Dean Brian Shannon, Texas Tech University School of Law; Profes- sor Christian Day, Syracuse University College of Law; Professor Dwight Aarons, Uni- versity of Tennessee College of Law; Ms. -

System of Church Tax in Germany

Dr. Jens Petersen The system of church tax in Germany The church tax will be 9% (or 8% in Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg) from the income tax. The churches, who have the status of a public body have the legal right to raise taxes. This based apon the Germen Constitution in conjunction with the federal church laws. These are the protestant, roman-kath., old-kath., some jewish and other small churches. The churches conclude wether they raise taxes and about the percentage. The administration itself is carreid-over to IRS because here is the established administration. This based on an bilateral contract. The IRS will get fees between 2% and 4% (according to the federal state). The churches have the legal right to get the data of their members from the IRS the fullfill their own tax-systems. At the time they did not need them because the IRS administrate the tax levy. The church tax is the most important part of the churches household. It will be about 70% to 80% of it. Other incomes: funds, fees, accomplishments (benefits) from the state (very old legal title; based on a treaty of 1804), other revenues. Income tax will be raised from income and salary a.s.o. The church tax from the income-tax will collect in conjunction with the income-tax (tax bill). The church tax of salary will retained by the employer and he refers them to the appropriate IRS. This refers it to the local church. Wether the employee is member of a church the employer will check out from the tax-card (Lohnsteuerkarte). -

1 Virtues Unfulfilled: the Effects of Land Value

VIRTUES UNFULFILLED: THE EFFECTS OF LAND VALUE TAXATION IN THREE PENNSYLVANIAN CITIES By ROBERT J. MURPHY, JR. A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL AT THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Robert J. Murphy, Jr. 2 To Mom, Dad, family, and friends for their support and encouragement 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my chair, Dr. Andres Blanco, for his guidance, feedback and patience without which the accomplishment of this thesis would not have been possible. I would also like to thank my other committee members, Dr. Dawn Jourdan and Dr. David Ling, for carefully prodding aspects of this thesis to help improve its overall quality and validity. I‟d also like to thank friends and cohorts, such as Katie White, Charlie Gibbons, Eric Hilliker, and my parents - Bob and Barb Murphy - among others, who have offered their opinions and guidance on this research when asked. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................. 4 LIST OF TABLES........................................................................................................... 9 LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................... 10 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .......................................................................................... 11 ABSTRACT................................................................................................................. -

Analyzing a Flat Income Tax in the Netherlands

TI 2007-029/3 Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper Analyzing a Flat Income Tax in the Netherlands Bas Jacobs,1,2,3,4,5 Ruud A. de Mooij6,7,3,4,5 Kees Folmer6 1 University of Amsterdam, 2 Tilburg University, 3 Tinbergen Institute, 4 Netspar, 5 CESifo, 6 CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, 7 Erasmus University Rotterdam, Tinbergen Institute The Tinbergen Institute is the institute for economic research of the Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, Universiteit van Amsterdam, and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Tinbergen Institute Amsterdam Roetersstraat 31 1018 WB Amsterdam The Netherlands Tel.: +31(0)20 551 3500 Fax: +31(0)20 551 3555 Tinbergen Institute Rotterdam Burg. Oudlaan 50 3062 PA Rotterdam The Netherlands Tel.: +31(0)10 408 8900 Fax: +31(0)10 408 9031 Most TI discussion papers can be downloaded at http://www.tinbergen.nl. Analyzing a Flat Income Tax in the Netherlands1 Bas Jacobs University of Amsterdam, Tilburg University, Tinbergen Institute, CentER, Netspar and CESifo ([email protected]) Ruud A. de Mooij CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, Erasmus University 2 Rotterdam, Tinbergen Institute, Netspar and CESifo Kees Folmer CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis ([email protected]) Abstract A flat tax rate on income has gained popularity in European countries. This paper assesses the attractiveness of such a flat tax in achieving redistributive objectives with the least cost to labour market performance. We do so by using a detailed applied general equilibrium model for the Netherlands. The model is empirically grounded in the data and encompasses decisions on hours worked, labour force participation, skill formation, wage bargaining between unions and firms, matching frictions, and a wide variety of institutional details.