Baseball's Antitrust Exemption - a Corked Bat for Owners? William S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

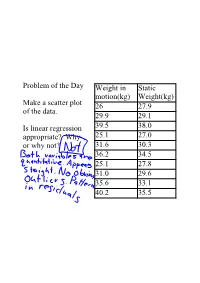

Problem of the Day Make a Scatter Plot of the Data. Is Linear Regression

Problem of the Day Weight in Static motion(kg) Weight(kg) Make a scatter plot 26 27.9 of the data. 29.9 29.1 Is linear regression 39.5 38.0 appropriate? Why 25.1 27.0 or why not? 31.6 30.3 36.2 34.5 25.1 27.8 31.0 29.6 35.6 33.1 40.2 35.5 Salary(in Problem of the Day Player Year millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 Is it appropriate to use George Foster 1982 2.0 linear regression Kirby Puckett 1990 3.0 to predict salary Jose Canseco 1991 4.7 from year? Roger Clemens 1996 5.3 Why or why not? Ken Griffey, Jr 1997 8.5 Albert Belle 1997 11.0 Pedro Martinez 1998 12.5 Mike Piazza 1999 12.5 Mo Vaughn 1999 13.3 Kevin Brown 1999 15.0 Carlos Delgado 2001 17.0 Alex Rodriguez 2001 22.0 Manny Ramirez 2004 22.5 Alex Rodriguez 2005 26.0 Chapter 10 ReExpressing Data: Get It Straight! Linear Regressioneasiest of methods, how can we make our data linear in appearance Can we reexpress data? Change functions or add a function? Can we think about data differently? What is the meaning of the yunits? Why do we need to reexpress? Methods to deal with data that we have learned 1. 2. Goal 1 making data symmetric Goal 2 make spreads more alike(centers are not necessarily alike), less spread out Goal 3(most used) make data appear more linear Goal 4(similar to Goal 3) make the data in a scatter plot more spread out Ladder of Powers(pg 227) Straightening is good, but limited multimodal data cannot be "straightened" multiple models is really the only way to deal with this data Things to Remember we want linear regression because it is easiest (curves are possible, but beyond the scope of our class) don't choose a model based on r or R2 don't go too far from the Ladder of Powers negative values or multimodal data are difficult to reexpress Salary(in Player Year Find an appropriate millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 linear model for the George Foster 1982 2.0 data. -

Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. CHAPTER 1 Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed King Arthur’s quest for it in the Middle Ages became a large part of his legend. Monty Python and Indiana Jones launched their searches in popular 1974 and 1989 movies. The mythic quest for the Holy Grail, the name given in Western tradition to the chal- ice used by Jesus Christ at his Passover meal the night before his death, is now often a metaphor for a quintessential search. In the illustrious history of baseball, the “holy grail” is a ranking of each player’s overall value on the baseball diamond. Because player skills are multifaceted, it is not clear that such a ranking is possible. In comparing two players, you see that one hits home runs much better, whereas the other gets on base more often, is faster on the base paths, and is a better fielder. So which player should rank higher? In Baseball’s All-Time Best Hitters, I identified which players were best at getting a hit in a given at-bat, calling them the best hitters. Many reviewers either disapproved of or failed to note my definition of “best hitter.” Although frequently used in base- ball writings, the terms “good hitter” or best hitter are rarely defined. In a July 1997 Sports Illustrated article, Tom Verducci called Tony Gwynn “the best hitter since Ted Williams” while considering only batting average. -

Tml American - Single Season Leaders 1954-2016

TML AMERICAN - SINGLE SEASON LEADERS 1954-2016 AVERAGE (496 PA MINIMUM) RUNS CREATED HOMERUNS RUNS BATTED IN 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE .422 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE 256 98 ♦MARK McGWIRE 75 61 ♦HARMON KILLEBREW 221 57 TED WILLIAMS .411 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 235 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 73 16 DUKE SNIDER 201 86 WADE BOGGS .406 61 MICKEY MANTLE 233 99 MARK McGWIRE 72 54 DUKE SNIDER 189 80 GEORGE BRETT .401 98 MARK McGWIRE 225 01 BARRY BONDS 72 56 MICKEY MANTLE 188 58 TED WILLIAMS .392 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 220 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 70 57 TED WILLIAMS 187 61 NORM CASH .391 01 JASON GIAMBI 215 61 MICKEY MANTLE 69 98 MARK McGWIRE 185 04 ICHIRO SUZUKI .390 09 ALBERT PUJOLS 214 99 SAMMY SOSA 67 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 183 85 WADE BOGGS .389 61 NORM CASH 207 98 KEN GRIFFEY Jr. 67 93 ALBERT BELLE 183 55 RICHIE ASHBURN .388 97 LARRY WALKER 203 3 tied with 66 97 LARRY WALKER 182 85 RICKEY HENDERSON .387 00 JIM EDMONDS 203 94 ALBERT BELLE 182 87 PEDRO GUERRERO .385 71 MERV RETTENMUND .384 SINGLES DOUBLES TRIPLES 10 JOSH HAMILTON .383 04 ♦ICHIRO SUZUKI 230 14♦JONATHAN LUCROY 71 97 ♦DESI RELAFORD 30 94 TONY GWYNN .383 69 MATTY ALOU 206 94 CHUCK KNOBLAUCH 69 94 LANCE JOHNSON 29 64 RICO CARTY .379 07 ICHIRO SUZUKI 205 02 NOMAR GARCIAPARRA 69 56 CHARLIE PEETE 27 07 PLACIDO POLANCO .377 65 MAURY WILLS 200 96 MANNY RAMIREZ 66 79 GEORGE BRETT 26 01 JASON GIAMBI .377 96 LANCE JOHNSON 198 94 JEFF BAGWELL 66 04 CARL CRAWFORD 23 00 DARIN ERSTAD .376 06 ICHIRO SUZUKI 196 94 LARRY WALKER 65 85 WILLIE WILSON 22 54 DON MUELLER .376 58 RICHIE ASHBURN 193 99 ROBIN VENTURA 65 06 GRADY SIZEMORE 22 97 LARRY -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

2017 Information & Record Book

2017 INFORMATION & RECORD BOOK OWNERSHIP OF THE CLEVELAND INDIANS Paul J. Dolan John Sherman Owner/Chairman/Chief Executive Of¿ cer Vice Chairman The Dolan family's ownership of the Cleveland Indians enters its 18th season in 2017, while John Sherman was announced as Vice Chairman and minority ownership partner of the Paul Dolan begins his ¿ fth campaign as the primary control person of the franchise after Cleveland Indians on August 19, 2016. being formally approved by Major League Baseball on Jan. 10, 2013. Paul continues to A long-time entrepreneur and philanthropist, Sherman has been responsible for establishing serve as Chairman and Chief Executive Of¿ cer of the Indians, roles that he accepted prior two successful businesses in Kansas City, Missouri and has provided extensive charitable to the 2011 season. He began as Vice President, General Counsel of the Indians upon support throughout surrounding communities. joining the organization in 2000 and later served as the club's President from 2004-10. His ¿ rst startup, LPG Services Group, grew rapidly and merged with Dynegy (NYSE:DYN) Paul was born and raised in nearby Chardon, Ohio where he attended high school at in 1996. Sherman later founded Inergy L.P., which went public in 2001. He led Inergy Gilmour Academy in Gates Mills. He graduated with a B.A. degree from St. Lawrence through a period of tremendous growth, merging it with Crestwood Holdings in 2013, University in 1980 and received his Juris Doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s and continues to serve on the board of [now] Crestwood Equity Partners (NYSE:CEQP). -

Sunday's Lineup 2018 WORLD SERIES QUEST BEGINS TODAY

The Official News of the 2018 Cleveland Indians Fantasy Camp Sunday, January 21, 2018 2018 WORLD SERIES QUEST BEGINS TODAY Sunday’s The hard work and relentless dedica- “It is about how we bring families, Lineup tion needed to be a winning team and neighbors, friends, business associates, gain a postseason berth begins long be- and even strangers together. fore the crowds are in the stands for “But we all know it is the play on the Opening Day. It begins on the practice field that is the spark of it all.” fields, in the classroom, and in the The Indians won an American League 7:00 - 8:25 Breakfast at the complex weight room. -best 102 games in 2017 and are poised Today marks that beginning, when the to be one of the top teams in 2018 due to 7:30 - 8:00 Bat selection 2018 Cleveland Indians Fantasy Camp its deeply talented core of players, award players make the first footprints at the -winning front office executives, com- Tribe’s Player Development Complex mitted ownership, and one of the best - if 8:30 - 8:55 Stretching on agility field here in Goodyear, AZ. not the best - managers in all of baseball Nestled in the scenic views of the Es- in Terry Francona. 9:00 -10:00 Instructional Clinics on fields trella Mountains just west of Phoenix, Named AL Manager of the year in the complex features six full practice both 2013 and 2016, the Tribe skipper fields, two half practice fields, an agility finished second for the award in 2017. -

Estimated Age Effects in Baseball

ESTIMATED AGE EFFECTS IN BASEBALL By Ray C. Fair October 2005 Revised March 2007 COWLES FOUNDATION DISCUSSION PAPER NO. 1536 COWLES FOUNDATION FOR RESEARCH IN ECONOMICS YALE UNIVERSITY Box 208281 New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8281 http://cowles.econ.yale.edu/ Estimated Age Effects in Baseball Ray C. Fair¤ Revised March 2007 Abstract Age effects in baseball are estimated in this paper using a nonlinear xed- effects regression. The sample consists of all players who have played 10 or more full-time years in the major leagues between 1921 and 2004. Quadratic improvement is assumed up to a peak-performance age, which is estimated, and then quadratic decline after that, where the two quadratics need not be the same. Each player has his own constant term. The results show that aging effects are larger for pitchers than for batters and larger for baseball than for track and eld, running, and swimming events and for chess. There is some evidence that decline rates in baseball have decreased slightly in the more recent period, but they are still generally larger than those for the other events. There are 18 batters out of the sample of 441 whose performances in the second half of their careers noticeably exceed what the model predicts they should have been. All but 3 of these players played from 1990 on. The estimates from the xed-effects regressions can also be used to rank players. This ranking differs from the ranking using lifetime averages because it adjusts for the different ages at which players played. It is in effect an age-adjusted ranking. -

Sports Figures Price Guide

SPORTS FIGURES PRICE GUIDE All values listed are for Mint (white jersey) .......... 16.00- David Ortiz (white jersey). 22.00- Ching-Ming Wang ........ 15 Tracy McGrady (white jrsy) 12.00- Lamar Odom (purple jersey) 16.00 Patrick Ewing .......... $12 (blue jersey) .......... 110.00 figures still in the packaging. The Jim Thome (Phillies jersey) 12.00 (gray jersey). 40.00+ Kevin Youkilis (white jersey) 22 (blue jersey) ........... 22.00- (yellow jersey) ......... 25.00 (Blue Uniform) ......... $25 (blue jersey, snow). 350.00 package must have four perfect (Indians jersey) ........ 25.00 Scott Rolen (white jersey) .. 12.00 (grey jersey) ............ 20 Dirk Nowitzki (blue jersey) 15.00- Shaquille O’Neal (red jersey) 12.00 Spud Webb ............ $12 Stephen Davis (white jersey) 20.00 corners and the blister bubble 2003 SERIES 7 (gray jersey). 18.00 Barry Zito (white jersey) ..... .10 (white jersey) .......... 25.00- (black jersey) .......... 22.00 Larry Bird ............. $15 (70th Anniversary jersey) 75.00 cannot be creased, dented, or Jim Edmonds (Angels jersey) 20.00 2005 SERIES 13 (grey jersey ............... .12 Shaquille O’Neal (yellow jrsy) 15.00 2005 SERIES 9 Julius Erving ........... $15 Jeff Garcia damaged in any way. Troy Glaus (white sleeves) . 10.00 Moises Alou (Giants jersey) 15.00 MCFARLANE MLB 21 (purple jersey) ......... 25.00 Kobe Bryant (yellow jersey) 14.00 Elgin Baylor ............ $15 (white jsy/no stripe shoes) 15.00 (red sleeves) .......... 80.00+ Randy Johnson (Yankees jsy) 17.00 Jorge Posada NY Yankees $15.00 John Stockton (white jersey) 12.00 (purple jersey) ......... 30.00 George Gervin .......... $15 (whte jsy/ed stripe shoes) 22.00 Randy Johnson (white jersey) 10.00 Pedro Martinez (Mets jersey) 12.00 Daisuke Matsuzaka .... -

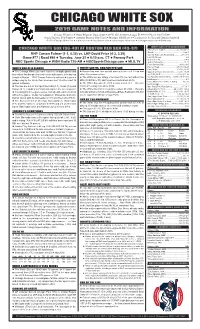

Chicago White Sox 2019 Game Notes and Information

CHICAGO WHITE SOX 2019 GAME NOTES AND INFORMATION Chicago White Sox Media Relations Department 333 W. 35th Street Chicago, Ill. 60616 Phone: 312-674-5300 Senior Director: Bob Beghtol Assistant Director: Ray García Manager: Billy Russo Coordinators: Joe Roti and Hannah Sundwall © 2019 Chicago White Sox whitesox.com loswhitesox.com whitesoxpressbox.com chisoxpressbox.com @whitesox WHITE SOX 2019 BREAKDOWN CHICAGO WHITE SOX (36-40) AT BOSTON RED SOX (43-37) After 76 | 77 in 2018 .....................25-51 | 26-51 Streak ...................................................... Lost 3 RHP Carson Fulmer (1-1, 6.35) vs. LHP David Price (4-2, 3.39) Current Trip | Last Homestand .............2-4 | 3-3 Game #77 | Road #40 Tuesday, June 25 6:10 p.m. CT Fenway Park Last 10 Games .............................................4-6 Series Record ............................................8-9-8 NBC Sports Chicago WGN Radio 720-AM NBCSportsChicago.com MLB.TV Series First Game..................................... 15-11 First | Second Half ............................36-40 | 0-0 Home | Road ................................20-17 | 16-23 WHITE SOX AT A GLANCE WHITE SOX VS. BOSTON RED SOX Day | Night ....................................13-23 | 23-17 The Chicago White Sox have lost three straight games and Boston has won four straight games to take a 4-1 lead and Opp. At or Above | Below .500 ......17-21 | 19-19 four of their last fi ve as they continue an eight-game, nine-day trip clinch the season series. vs. RHS | LHS .............................. 25-30 | 11-10 tonight in Boston … RHP Carson Fulmer is scheduled to open a The White Sox are hitting .215/.285/.374 (35-163) with a 7.66 vs. -

Free Ebook Library the Little Book of Baseball Law (ABA Little

Free Ebook Library The Little Book Of Baseball Law (ABA Little Books Series) The game of baseball has often resulted in brawls, both on the field and in the courtroom, and from the 1890's on, much of what baseball is today has been shaped by the law. In eighteen chapters, this eye-opening book discusses cases that involved rules of the game, new stadium construction, ownership of baseball memorabilia, injured spectators, television contracts, and much more. Series: ABA Little Books Series Paperback: 248 pages Publisher: American Bar Association; 12 edition (September 2009) Language: English ISBN-10: 1604421002 ISBN-13: 978-1604421002 Product Dimensions: 5.7 x 0.6 x 8.7 inches Shipping Weight: 15.2 ounces (View shipping rates and policies) Average Customer Review: 5.0 out of 5 stars 3 customer reviews Best Sellers Rank: #465,748 in Books (See Top 100 in Books) #43 in Books > Law > Specialties > Sports #743 in Books > Sports & Outdoors > Baseball #1250 in Books > Law > Administrative Law Honestly I bought this book thinking on a BASEBALL Law book, but I was surprised on how interesting it is. It has real legal facts and cases that has happened in baseball. Easy to read (I finished it in one afternoon - watching a game ..) The Little White Book of Baseball Law is well worth the price. The authors, John H. Minan and Kevin Cole, have blended 226 pages of fascinating legal disputes from baseball's history with an examination of some of the more arcane rules in baseball. This lawyer/reader, as an 11 year old Cleveland Indians fan, without a television, began my love of baseball around the time I "heard" Willie Mays' famous over the head catch in the 1954 World Series. -

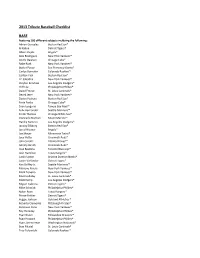

2013 Tribute Baseball Checklist BASE

2013 Tribute Baseball Checklist BASE Featurng 100 different subjects inclduing the following: Adrian Gonzalez Boston Red Sox® Al Kaline Detroit Tigers® Albert Pujols Angels® Alex Rodriguez New York Yankees® Andre Dawson Chicago Cubs® Babe Ruth New York Yankees® Buster Posey San Francisco Giants® Carlos Gonzalez Colorado Rockies™ Carlton Fisk Boston Red Sox® CC Sabathia New York Yankees® Clayton Kershaw Los Angeles Dodgers® Cliff Lee Philadelphia Phillies® David Freese St. Louis Cardinals® Derek Jeter New York Yankees® Dustin Pedroia Boston Red Sox® Ernie Banks Chicago Cubs® Evan Longoria Tampa Bay Rays™ Felix Hernandez Seattle Mariners™ Frank Thomas Chicago White Sox® Giancarlo Stanton Miami Marlins™ Hanley Ramirez Los Angeles Dodgers® Jacoby Ellsbury Boston Red Sox® Jered Weaver Angels® Joe Mauer Minnesota Twins® Joey Votto Cincinnati Reds® John Smoltz Atlanta Braves™ Johnny Bench Cincinnati Reds® Jose Bautista Toronto Blue Jays® Josh Hamilton Texas Rangers® Justin Upton Arizona Diamondbacks® Justin Verlander Detroit Tigers® Ken Griffey Jr. Seattle Mariners™ Mariano Rivera New York Yankees® Mark Teixeira New York Yankees® Matt Holliday St. Louis Cardinals® Matt Kemp Los Angeles Dodgers® Miguel Cabrera Detroit Tigers® Mike Schmidt Philadelphia Phillies® Nolan Ryan Texas Rangers® Prince Fielder Detroit Tigers® Reggie Jackson Oakland Athletics™ Roberto Clemente Pittsburgh Pirates® Robinson Cano New York Yankees® Roy Halladay Philadelphia Phillies® Ryan Braun Milwaukee Brewers™ Ryan Howard Philadelphia Phillies® Ryan Zimmerman Washington Nationals® Stan Musial St. Louis Cardinals® Troy Tulowitzki Colorado Rockies™ Willie Mays San Francisco Giants® AUTOGRAPHS On-Card Autographs At least 150 different cards including the following: Adam Jones Baltimore Orioles® Adrian Gonzalez Boston Red Sox® Albert Pujols Angels® Albert Belle Cleveland Indians® Andre Dawson Chicago Cubs® Andy Pettitte New York Yankees® Bob Gibson St. -

Nondestructive Testing Detects Altered Baseball Bats

From NDT Technician , Vol. 11, No. 4, pp: 1 –5. Copyright © 2012 The American Society for Nondestructive Testing, Inc. The American Society for Nondestructive Testing www.asnt.org FOCUS Nondestructive Testing Detects Altered Baseball Bats Daniel A. Russell* Corked Wood Baseball Bats The prevalence of corked bats in X-rays and CT scans. Pete Rose Major League Baseball is not known was frequently accused of using The history of the game of baseball because players are caught only corked bats during his 1985 chase is peppered with interesting stories when the doctored bat breaks, of the all-time hits record, but no of attempts to break the rules. revealing the cork interior. For broken bats ever exposed cork. Managers have been caught stealing example, in 1974, New York Several of Rose’s bats from 1985 signs; groundskeepers have altered Yankees’ Graig Nettles shattered his are now in private collections. Cthe playing conditions of the field bat, sending several superballs Recent X-ray scans of two of these to the advantage of the home team; bouncing around home plate. In bats show that they were indeed pitchers have used petroleum jelly, 1987, Houston Astros outfielder corked. 3 mud, emery boards, or thumbtacks Billy Hatcher’s bat broke and one of Following the Sosa corked bat to alter the surface of the baseball; the pieces ended up in the hands of incident in 2003, the Major League and Major League Baseball players Chicago Cubs third baseman Keith Baseball commissioner’s office like Albert Belle, Norm Cash, Graig Moreland, who promptly showed ordered that X-ray scans be taken Nettles, and Sammy Sosa, have used the exposed cork filling to the of the rest of Sosa’s bats, including 1,4 corked bats.