Demographic Outlook for the European Union 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government Debt up to 100.5% of GDP in Euro Area up to 92.9% of GDP in EU

84/2021 - 22 July 2021 First quarter of 2021 Government debt up to 100.5% of GDP in euro area Up to 92.9% of GDP in EU At the end of the first quarter of 2021, still largely impacted by policy measures to mitigate the economic and social impact of the coronavirus pandemic and recovery measures, which continued to materialise in increased financing needs, the government debt to GDP ratio in the euro area exceeded 100% for the first time – the ratio stood at 100.5%, compared with 97.8% at the end of the fourth quarter of 2020. In the EU, the ratio increased from 90.5% to 92.9%. Compared with the first quarter of 2020, the government debt to GDP ratio rose in both the euro area (from 86.1% to 100.5%) and the EU (from 79.2% to 92.9%). At the end of the first quarter of 2021, debt securities accounted for 82.6% of euro area and for 82.2% of EU general government debt. Loans made up 14.2% and 14.7% respectively and currency and deposits represented 3.2% of euro area and 3.1% of EU government debt. Due to the involvement of EU Member States' governments in financial assistance to certain Member States, quarterly data on intergovernmental lending (IGL) are also published. The share of IGL as percentage of GDP at the end of the first quarter of 2021 accounted for 2.0% in the euro area and to 1.7% in the EU. These data are released by Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union. -

Effective Evangelistic Strategies for North Korean Defectors (Talbukmin) in South Korea

ABSTRACT Effective Evangelistic Strategies for North Korean Defectors (Talbukmin) in South Korea South Korean churches eagerness for spreading the gospel to North Koreans is a passion. However, because of the barriers between the two Koreas, spreading the Good News is nearly impossible. In the middle of the 1990’s, numerous North Koreans defected to China to avoid starvation. Many South Korean missionaries met North Koreans directly and offered the gospel along with necessities for survival in China. Since the early of 2000’s, many Talbukmin have entered South Korea so South Korean churches have directly met North Koreans and spread the gospel. However, the fruits of evangelism are few. South Korean churches find that Talbukmin are very different from South Koreans in large part due to the sixty-year division. South Korean churches do not know or fully understand the characteristics of the Talbukmin. The evangelism strategies and ministry programs of South Korean churches, which are designed for South Koreans, do not adapt well to serve the Talbukmin. This research lists and describes the following five theories to be used in the development of the effective evangelistic strategies for use with the Talbukmin and for use to interpret the interviews and questionnaires: the conversion theory, the contextualization theory, the homogenous principle, the worldview transformation theory, and the Nevius Mission Plan. In the following research exploration of the evangelization of Talbukmin in South Korea occurs through two major research agendas. The first agenda is concerned with the study of the characteristics of Talbukmin to be used for the evangelists’ understanding of the depth of differences. -

Information Guide Europe on the Internet

Information Guide Europe on the Internet A selection of useful websites, databases and documents for information on the European Union and the wider Europe Ian Thomson Director, Cardiff EDC Latest revision: August 2017 © Cardiff EDC Europe on the Internet Contents • Searching for European information • Legislative, judicial and policy-making information • Keeping up-to-date • Information on EU policies and countries • Grants and loans – Statistics • Contact information • Terminological, linguistic and translation information In addition to textual hyperlinks throughout this guide, many of the images are also hyperlinks to further information Europe on the Internet. © Ian Thomson, Cardiff EDC, August 2017 Europe on the Internet Searching for European Information Europe on the Internet. © Ian Thomson, Cardiff EDC, August 2017 Searching for European information The EU’s own search engine to find information from EU Institutions & Agencies published on EUROPA, the EU’s portal [EUROPA Search does not find information in EUR-Lex] The European Journalism Centre set up this Search Europa service, which uses the functionality of Google to search the EUROPA portal [Includes results from EUR-Lex] FIND-eR (Find Electronic Resources) will help you find EU publications, academic books, journal articles, etc. on topics of interest to the EU [Offers hyperlinks to full text of sources if freely available, or via use of a Link-Resolver] [Formerly known as ECLAS] EU Law and Publications: Use the Search Centre to search for EU documents [EU law – EUR-Lex] and EU publications [EU Bookshop] + EU websites and Summaries of EU Legislation EU Bookshop: from here you can buy printed copies or freely download electronic copies of EU publications. -

Eurostat: Recognized Research Entity

http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/overview This list enumerates entities that have been recognised as research entities by Eurostat. In order to apply for recognition please consult the document 'How to apply for microdata access?' http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/overview The researchers of the entities listed below may submit research proposals. The research proposal will be assessed by Eurostat and the national statistical authorities which transmitted the confidential data concerned. Eurostat will regularly update this list and perform regular re-assessments of the research entities included in the list. Country City Research entity English name Research entity official name Member States BE Antwerpen University of Antwerp Universiteit Antwerpen Walloon Institute for Evaluation, Prospective Institut wallon pour l'Evaluation, la Prospective Belgrade and Statistics et la Statistique European Economic Studies Department, European Economic Studies Department, Bruges College of Europe College of Europe Brussels Applica sprl Applica sprl Brussels Bruegel Bruegel Center for Monitoring and Evaluation of Center for Monitoring and Evaluation of Brussels Research and Innovation, Belgian Science Research and Innovation, Service public Policy Office fédéral de Programmation Politique scientifique Centre for European Social and Economic Centre de politique sociale et économique Brussels Policy Asbl européenne Asbl Brussels Centre for European Policy Studies Centre for European Policy Studies Department for Applied Economics, -

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 16.12.2019 COM(2019)

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 16.12.2019 COM(2019) 638 final REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION ON THE WORKING OF COMMITTEES DURING 2018 {SWD(2019) 441 final} EN EN REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION ON THE WORKING OF COMMITTEES DURING 2018 In accordance with Article 10(2) of Regulation (EU) No 182/2011 laying down the rules and general principles concerning mechanisms for control by Member States of the Commission’s exercise of implementing powers1 (the ‘Comitology Regulation’), the Commission hereby presents the annual report on the working of committees for 2018. This report gives an overview of developments in the comitology system in 2018 and a summary of the committees’ activities. It is accompanied by a staff working document containing detailed statistics on the work of the individual committees. 1. OVERVIEW OF DEVELOPMENTS IN THE COMITOLOGY SYSTEM IN 2018 1.1. General development As described in the 2013 annnual report2, all comitology procedures provided for in the ‘old’ Comitology Decision3, with the exception of the regulatory procedure with scrutiny, were automatically adapted to the new comitology procedures provided for in the Comitology Regulation. In 2018, the comitology committees were therefore operating under the procedures set out in the Comitology Regulation, i.e. advisory (Article 4) and examination (Article 5), as well as under the regulatory procedure with scrutiny set out in Article 5a of the Comitology Decision. The Interinstitutional Agreement on Better Law-Making of 13 April 20164 recalls, in its point 27, the need to align the regulatory procedure with scrutiny: ‘The three institutions acknowledge the need for the alignment of all existing legislation to the legal framework introduced by the Lisbon Treaty, and in particular the need to give high priority to the prompt alignment of all basic acts which still refer to the regulatory procedure with scrutiny. -

The European System of Interoperable Business Registers

European profiling Profiling allows a view KS-03-13-411-EN-C sees the whole elephant of the actual economic activity KS-03-13-411-EN-C Compact guides Like blind men in the old Indian fable, confronted for the first With profiling the National Statistical Institutes will correctly esti- time with an elephant and unable to agree on their perceptions, mate turnover. each only touching a different part, multinational enterprise Without profiling, e.g., four activities are observed in country 1 and groups cannot be explained by a purely national view based on the total turnover is 900. This includes turnover generated by intra- legal units. European profiling relies on the groups’ own under- group activities (Segments N3, N4 and parts of N1, N2). standing of their economic and organisational structures, allowing After profiling, in the example, 2 activities ‘disappear’ because they in- NSIs through direct contacts with the groups to define enterprises ternally serve the group (N3, N4). Intra-group turnover is eliminated. in a more relevant and consistent manner. This approach is not restricted to Europe as it includes all parts of a European group, Without profiling Total turnover within and outside Europe. of the group in country 1: 900 • European-Statistical-System-wide gains NACE N1 Turnover: 400 NACE N2 NACE N3 NACE N4 – The country of the headquarter profiles for all the countries Turnover: 250 (wholesale) involved (transport) Turnover: 150 Turnover: 100 – Enterprises of one group are defined consistently for all Euro- pean business statistics With profiling Total turnover – Centrally defined enterprises made available for all national of the group statistics NACE N1 in country 1: 500 Turnover: 300 NACE N2 • Benefits for respondents Turnover: 200 N3 and N4: intra-group – Profilers and the group talk the same language activities disappear – NSIs offer the group a central contact point – Profiling decreases the response burden for a group Profiling also improves the description of activities through NACE code and their harmonisation across countries. -

DOES COHESION POLICY REDUCE EU DISCONTENT and EUROSCEPTICISM? Andrés Rodríguez-Pose Lewis Dijkstra

DOES COHESION POLICY REDUCE EU DISCONTENT AND EUROSCEPTICISM? Andrés Rodríguez-Pose Lewis Dijkstra WORKING PAPER A series of short papers on regional Research and indicators produced by the Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy WP 04/2020 Regional and Urban Policy B ABSTRACT Some regions in Europe that have been heavily supported by the European Union’s cohesion policy have recently opted for parties with a strong Eurosceptic orientation. The results at the ballot box have been put forward as evidence that cohesion policy is ineffective for tackling the rising, European-wide wave of discontent. However, the evidence to support this view is scarce and, often, contradictory. This paper analyses the link between cohesion policy and the vote for Eurosceptic parties. It uses the share of votes cast for Eurosceptic parties in more than 63,000 electoral districts in national legislative elections in the EU28 to assess whether cohesion policy investment since 2000 has made a difference for the electoral support for parties opposed to European integration. The results indicate that cohesion policy investment is linked to a lower anti-EU vote. This result is robust to employing different econometric approaches, to considering the variety of European development funds, to different periods of investment, to different policy domains, to shifts in the unit of analysis, and to different levels of opposition by parties to the European project. The positive impact of cohesion policy investments on an area and a general awareness of these EU investments are likely to contribute to this result. Keywords: Euroscepticism, anti-system voting, populism, cohesion policy, elections, regions, Europe LEGAL NOTICE No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. -

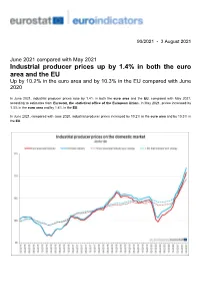

Industrial Producer Prices up by 1.4% in Both the Euro Area and the EU up by 10.2% in the Euro Area and by 10.3% in the EU Compared with June 2020

90/2021 - 3 August 2021 June 2021 compared with May 2021 Industrial producer prices up by 1.4% in both the euro area and the EU Up by 10.2% in the euro area and by 10.3% in the EU compared with June 2020 In June 2021, industrial producer prices rose by 1.4% in both the euro area and the EU, compared with May 2021, according to estimates from Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union. In May 2021, prices increased by 1.3% in the euro area and by 1.4% in the EU. In June 2021, compared with June 2020, industrial producer prices increased by 10.2% in the euro area and by 10.3% in the EU. Monthly comparison by main industrial grouping and by Member State Industrial producer prices in the euro area in June 2021, compared with May 2021, increased by 3.3% in the energy sector, by 1.3% for intermediate goods, by 0.4% for capital goods and by 0.3% for durable and non-durable consumer goods. Prices in total industry excluding energy increased by 0.7%. In the EU, industrial producer prices increased by 3.4% in the energy sector, by 1.4% for intermediate goods, by 0.4% for capital goods and for non-durable consumer goods and by 0.3% for durable consumer goods. Prices in total industry excluding energy increased by 0.8%. The highest increases in industrial producer prices were recorded in Denmark (+5.1%), Estonia (+4.6%) and Latvia (+3.1%), while the only decrease was observed in Ireland (-0.3%). -

The Governance of the European Statistical

The Governance of the European Statistical Eurostat A1 Ms Åsa Jacob System (ESS) Mr Aaron Cachia Mr Dietmar Maass January 2018 Content of the presentation • Introduction to the European Statistical System (ESS) • Main governance bodies in the ESS • European Statistical System Committee (ESSC) • Partnership Group (PG) • DGINS Conference • European Statistical Advisory Committee (ESAC) • European Statistical Governance Advisory Board (ESGAB) • ESS Website • Question Time 2 The European Statistical System • Partnership between Eurostat and the national statistical authorities • Defined in European Statistics Regulation 223/2009 Member states collect and Eurostat processes the received data process the national data and disseminates European official statistics 3 Regulation 223/09 on European statistics • ESS is legally recognised and defined for the first time • Introduces the statistical principles (Art 2): • professional independence • impartiality • objectivity • reliability • statistical confidentiality • cost effectiveness • Establishes the ESS Committee (Art 7) • Introduces concept of collaborative networks (Art 15) • Introduces European approach to statistics (Art 16) 4 The European Statistical System governance bodies 5 Statistical governance structure Political level Commission Council Europ. Parliament Strategic advice ESSC DGINS ESF STC Strategic level PG ESF Bureau Management Directors Groups VIG level VIN Working level Working groups Task forces ESCBFolie 6 The European Statistical System Committee (ESSC) • At the heart of the -

![Green Growth 1.0 and 2.0 Towards Meaningful Environmental Policy in South Korea [Note]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3615/green-growth-1-0-and-2-0-towards-meaningful-environmental-policy-in-south-korea-note-1523615.webp)

Green Growth 1.0 and 2.0 Towards Meaningful Environmental Policy in South Korea [Note]

Green Growth 1.0 and 2.0 towards Meaningful Environmental Policy in South Korea [Note] Item Type Article; text Authors Duong, Alanna T. Citation 31 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. L. 357 (2014) Publisher The University of Arizona James E. Rogers College of Law (Tucson, AZ) Journal Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law Rights Copyright © The Author(s) Download date 28/09/2021 06:16:20 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/658911 GREEN GROWTH 1.0 AND 2.0: TOWARDS MEANINGFUL ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY IN SOUTH KOREA Alanna T. Duong* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. IN TRO D UCTIO N .................................................................................................. 358 II. THE EMERGENCE OF GREEN GROWTH ............................................................ 361 A. Sustainable Development as the Basic Framework .................................. 361 B. Green Growth as an Interrelated and Interchangeable Concept ................. 363 III. SOUTH KOREA: A PARADIGM SHIFT FROM QUANTITATIVE GROWTH TO Q UA LITATIVE G ROW TH ........................................................................................ 366 A. The Old Quantitative Growth M odel ......................................................... 366 B. A New Growth Engine Announced: Low Carbon, Green Growth ........... 367 C. Paving the Way: The Global Green New Deal .......................................... 369 D. The Completed Vision: The Framework Act, National Strategy, and F iv e-Y -

Nber Working Paper Series Resource Misallocation in European Firms: the Role of Constraints, Firm Characteristics and Managerial

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES RESOURCE MISALLOCATION IN EUROPEAN FIRMS: THE ROLE OF CONSTRAINTS, FIRM CHARACTERISTICS AND MANAGERIAL DECISIONS Yuriy Gorodnichenko Debora Revoltella Jan Svejnar Christoph T. Weiss Working Paper 24444 http://www.nber.org/papers/w24444 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2018 We thank Russell Cooper, Peter Klenow, Albert Park and seminar participants in Berkeley, Bristol, Padova, at the 2018 ASSA meeting (Philadelphia), the CompNet 7th Annual Conference (Halle), the conference “Investment in the new monetary and financial environment” (Paris), the 2019 EEA Congress (Manchester), for helpful discussion and comments. In preparing this paper, Yuriy Gorodnichenko and Jan Svejnar worked under a grant from the European Investment Bank. Jan Svejnar was also supported by the Czech Science Foundation (grant No. 15-24642S). The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Investment Bank or the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2018 by Yuriy Gorodnichenko, Debora Revoltella, Jan Svejnar, and Christoph T. Weiss. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Resource Misallocation in European Firms: The Role of Constraints, Firm Characteristics and Managerial Decisions Yuriy Gorodnichenko, Debora Revoltella, Jan Svejnar, and Christoph T. Weiss NBER Working Paper No. 24444 March 2018, Revised June 2020 JEL No. -

Report on the 2019 Elections to the European Parliament

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 19.6.2020 COM(2020) 252 final COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL AND THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE Report on the 2019 elections to the European Parliament {SWD(2020) 113 final} EN EN 1. Introduction The elections to the European Parliament are among the largest democratic exercises in the world. In May 2019, European Union citizens directly elected 751 Members of the European Parliament (MEPs)1 from over 15,000 parliamentary candidates, with over 250 million votes cast in Europe. The record-high turnout in the 2019 European Parliament elections (‘the elections’), the highest in 25 years, shows the vibrancy of our democracy and the renewed engagement of EU citizens in shaping the future of the EU, especially among its youth. The post-election survey shows that EU citizens believe that their voice counts in the EU as never before.2 A truly European debate emerged on topics such as the economy, climate change and human rights and democracy.3 These were also the most digital European Parliamentary elections. A large proportion EU citizens use the internet,4 and online sources and social media play an increased role in our European democratic debate, giving political actors unprecedented opportunities to get their message across, and even greater access to the debate for citizens. The Cambridge Analytica scandal5 revealed a darker side to these advances. It brought to light interference in elections exploiting online social networks to mislead citizens and manipulate the debate and voters’ choices,6 by concealing or misrepresenting key information such as the origin and political intent of communications, their sources and their funding.