“When the Gunfire Ends”: Deconstructing PTSD Among Military Veterans in Marvel's the Punisher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPSTATE ECHOES Is Arch Merrill's Ninth Book

UPSTATE EcnfJes by ARCH MERRILL UPSTATE ECHOES is Arch Merrill's ninth book. like the others that have won so many thousands of readers, it is a regional book. Only, as its title implies, it embraces a larger region. Besides many a tale of the Western New York countryside about which Storyteller Merrill has been writing for more than a decade, in his lively, distinctive style, this new book offers fascinating chapters about other Upstate regions, among them the North Country, the Niagara Frontier and the Southern Tier. Through its pages walk colorful figures of the Upstate past- the fair lady a North Coun try grandee won by the toss of a coin- the onetime King of Spain who held court in the backwoods- the fabulous Elbert Hubbard, "The Fro" of East Aurora- the missionary martyrs and a silver-tongued infidel, natives of the land of Finger Lakes, who made his tory in their time- the movie stars who once made Ithaca, far above Cayuga's waters, a little Hollywood- the daredevils who through the years in barrels and boats and on tight ropes have sought to conquer the "thunder water" of Niagara. The past comes to life again in stories of historic mansions, covered bridges, Indian council fires and the oldtime glory of Char lotte, Rochester's lake port that once was "The Coney Island of the West." You will meet such interesting people as the last surviving sextuplet in America and the "The Wonderful Man" who leaped from a parachute at the age of 81. • UPSTATE ECHOES Other Books by ARcH MERRILL A RIVER RAMBLE THE LAKES COUNTRY THE RIDGE THE TOWPATH ROCHESTER SKETCH BOOK STAGE COACH TOWNS TOMAHAWKS AND OLD LACE LAND OF THE SENECAS UPSTATE ECHOES BY ARCH MERRILL Being an Assemblage of Stories about Unusual People, Places and Events in the Upstate New York of Long Ago and of Only Yesterday Many af Them Appeared in Whole or in Part in the Rochester N.Y. -

International Theatrical Marketing Strategy

International Theatrical Marketing Strategy Main Genre: Action Drama Brad Pitt Wardaddy 12 Years a Slave, World War Z, Killing Them Softly Moneyball, Inglourious Basterds, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button Shia LaBeouf Bible Charlie Countryman, Lawless, Transformers: Dark of the Moon, Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen, Eagle Eye, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull Logan Lerman Norman Noah, Percy Jackson: Sea of Monsters, Stuck in Love, The Perks of being a Wallflower, The Three Musketeers Michael Peña Gordo Cesar Chavez, American Hustle, Gangster Squad, End of Watch, Tower Heist, 30 Minutes or Less CONFIDENTIAL – DO NOT DISTRIBUTE Jon Bernthal Coon-Ass The Wolf of Wall Street, Grudge Match, Snitch, Rampart, Date Night David Ayer Director Sabotage, End of Watch Target Audience Demographic: Moviegoers 17+, skewing male. Psychographic: Fans of historical drama, military fans. Fans of the cast. Positioning Statment At the end of WWII, a battle weary tank commander must lead his men into one last fight deep in the heart of Nazi territory. With a rookie soldier thrust into his platoon, the crew of the Sherman Tank named Fury face overwhelming odds of survival. Strategic Marketing & Research KEY STRENGTHS Brad Pitt, a global superstar. Pitt’s star power certainly is seen across the international market and can be used to elevate anticipation of the film. This is a well-crafted film with standout performances. Realistic tank action is a key interest driver for this film. A classic story of brotherhood in WWII that features a strong leader, a sympathetic rookie, and three other entertaining, unique personalities to fill out the crew. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Palabra Clave ISSN: 0122-8285 Universidad de La Sabana Donoso Munita, José Agustín; Penafiel Durruty, Mariano Alejandro Transmedial Transduction in the Spider-Verse Palabra Clave, vol. 20, no. 3, 2017, July-September, pp. 763-787 Universidad de La Sabana DOI: https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.8 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=64954578008 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Transmedial Transduction in the Spider-Verse José Agustín Donoso Munita1 Mariano Alejandro Penafiel Durruty2 Recibido: 2016-09-09 Aprobado por pares: 2017-02-17 Enviado a pares: 2016-09-12 Aceptado: 2017-03-16 DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.8 Para citar este artículo / to reference this article / para citar este artigo Donoso Munita, J.A. y Penafiel Durruty, M.A. (2017). Transmedial transduction in the spider-verse. Palabra Clave, 20(3), 763-787. DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.8 Abstract Since Spider-Man was born from the hands of Stan Lee and Steve Ditko in 1962, thousands of versions of the arachnid have been created. Among them, two call the attention of this investigation: Spider-Man India and Supaidaman (1978), from Japan. By using a comparative study of the he- ro’s journey between these two and the original Spider-Man, this study at- tempts to understand transduction, made to generate cultural proximity with the countries where the adaptations were made. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Lot 11 Lot 26 Lot 53

Lot 11 Lot 26 Lot 53 From the desk at T Bar... Welcome to the 21st Kuntz Simmental Farm, McIntosh Livestock, SAJ Simmentals Annual Bull Sale, March 17, 2020 at the Lloydminster Exhibition Grounds, Lloydminster, Saskatchewan. For over two decades, this sale has been selling high quality Simmental bulls to the livestock industry. Their success has been consumer demand from the commercial livestock producers to many purebred breeders who have chosen to select high value bulls. The offering consists of a powerful lineup of seventy yearling bulls. The red and the black purebreds are exciting, stylish and have muscle, with deep body shape… exactly what you want your steer calves to possess. The fullbloods are burly and powerful and a well-kept secret. We will never have enough fullbloods in this offering, as they are meat machines. This sale has grown into a source for superior sire prospects, whether you are looking for domestics or fullbloods. Each year, Blair and Stephanie go to Canadian Western Agribition to receive their award, People’s Choice Championship in the commercial barn, but it is not without effort for 365 days of the year. Their pen at Agribition captured the Supreme Champion Bulls and of course, the Champion Simmental Pen. Locally, at Edam Fall Fair they duplicated the task and at Lloydminster Stockade Roundup, the McIntoshs exhibited the Reserve Grand Simmental Bull in the open show…they all sell! The bulls will be on display at Lloyd Ex the day prior, do not hesitate to stop by or feel free to give any of the boys a call as they will be pleased to discuss the cattle business, the bulls and those that will fit your breeding needs. -

Daredevils Dazzle Lantz Gym Er, the Faculty Senate Has D Other Reasons, Such As by BRIAN HUCHEL 'This Is Great Because the Audience Always Comedic Antics of Halftime

Eastern Illinois University The Keep January 1993 1-26-1993 Daily Eastern News: January 26, 1993 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1993_jan Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: January 26, 1993" (1993). January. 11. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_1993_jan/11 This is brought to you for free and open access by the 1993 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in January by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ntal stem iable ti on much students might pay textbooks if Eastern's Rental Service is elimi anyone 's guess. current textbook rental nt cost, a junior special on major with 15 hours y $232 for a semester's of books. or a freshman science major might pay or the same number of universities such as the "ty of Illinois at Urbana aign are often used for "son. The U of I students y their books at Follet 's re in Urbana pay about $350 per semester depend- their course load, said Paul MIKE ANSCHUETZ/Senior phot<?9!'8Pher Follett's district manager. Ftiday the 13th's "Jason" makes an appearance with the Bud Light Daredevils, completillg an acrobatic slam dunk during the halftime of Eastern students pay $59 the men's Eastern-Northern basketball game Monday night at the Lantz Gym. The game proved as thrilling as the Daredevil's show, with the ester to rent their books Panther's winning 65-63. See story page 12. !ban paying the higher num tered around, economic have moved to the forefronl textbook rental debate. -

Dead Man Logan Vol. 1: Sins of the Father Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DEAD MAN LOGAN VOL. 1: SINS OF THE FATHER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ed Bisson | 140 pages | 01 Aug 2019 | Panini Publishing Ltd | 9781846539794 | English | Tunbridge Wells, United Kingdom Dead Man Logan Vol. 1: Sins Of The Father PDF Book Average rating 3. Fantastic Four by Dan Slott Vol. Logan teams up with Hawkeye to humorous effect, not to mention that weird gang of D-league X-Men. About Ed Brisson. Nov 26, Mark T. Brisson and company are a bit rushed by the page count, but it hits the right emotional notes. Comeback 5. Definitely curious as to what Brisson has in store for Logan back in his home world. But yeah awesome book! Perfect for one sitting. Une erreur est survenue. And he ain't going to get better this time. Rows: Columns:. Cancel Create Link. Old Man Logan is dying. The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. She recruits Sin, Crossbones and Mysterio to try and put the plan in action. The villain means to set in motion the mutant massacre at the crux of Old Man Logan's apocalyptic future timeline. Sick from the Adamantium coating his skeleton, Logan's search for a cure has led to nothing but dead ends. It's pretty good. This process takes no more than a few hours and we'll send you an email once approved. Qssxx Dang that's good. Books by Ed Brisson. It wasn't bad but it seemed to hover between silly and serious, swinging from one to the other at odd times. -

Sexual Violence and the Us Military: the Melodramatic Mythos of War

SEXUAL VIOLENCE AND THE U.S. MILITARY: THE MELODRAMATIC MYTHOS OF WAR AND RHETORIC OF HEALING HEROISM Valerie N. Wieskamp Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication and Culture, Indiana University April 2015 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _________________________ Chair: Robert Terrill, Ph.D. _________________________ Purnima Bose, Ph.D. _________________________ Robert Ivie, Ph.D. _________________________ Phaedra Pezzullo, Ph.D. April 1, 2014 ii © Copyright 2015 Valerie N. Wieskamp iii Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the help of colleagues, friends, and family, a few of which deserve special recognition here. I am forever grateful to my dissertation advisor, Dr. Robert Terrill. His wisdom and advice on my research and writing throughout both this project and my tenure as a graduate student has greatly enhanced my academic career. I would also like to express my gratitude to my dissertation committee, Dr. Robert Ivie, Dr. Phaedra Pezzullo, Dr. Purnima Bose, and the late Dr. Alex Doty for the sage advice they shared throughout this project. I am indebted to my dissertation-writing group, Dr. Jennifer Heusel, Dr. Jaromir Stoll, Dave Lewis, and Maria Kennedy. The input and camaraderie I received from them while writing my dissertation bettered both the quality of my work and my enjoyment of the research process. I am also fortunate to have had the love and support of my parents, John and Debbie Wieskamp, as well as my sisters, Natalie and Ashley while completing my doctorate degree. -

ASM 129 Investment Memo V4

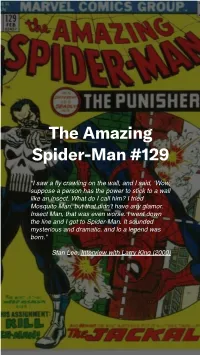

The Amazing Spider-Man #129 “I saw a fly crawling on the wall, and I said, ‘Wow, suppose a person has the power to stick to a wall like an insect. What do I call him? I tried Mosquito Man, but that didn’t have any glamor. Insect Man, that was even worse. I went down the line and I got to Spider-Man. It sounded mysterious and dramatic, and lo a legend was born.” Stan Lee, Interview with Larry King (2000) Background Otis recently acquired a 9.8 CGC Grade “Amazing Spider-Man #129” comic book. This document aims to share the story of this asset. Table Of Contents OTIS OVERVIEW 4 HIGHLIGHTS 5 THE COMIC BOOK INDUSTRY 7 COMIC BOOK AGES 11 THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN #129 14 GRADE & CONDITION 17 SUMMARY OF HISTORICAL SALES 18 INVESTMENT RISKS 22 2 What Is Otis Everyone has their thing. Maybe yours is sneakers, or maybe it's contemporary art. Whatever it is, you get it — the value assigned to a certain item, its cultural significance, why it matters. But more often than not, ownership of grails is out of the picture, whether because fewer than 100 were made, or because that six-figure price tag just doesn't work with your budget. At Otis, we turn aficionados into shareholders. We believe in transparency, liquidity, and trusting your own gut. We're democratizing an otherwise closed market and making these alternative assets accessible. Own shares in the things that you value, and whose value you understand and build a portfolio better suited to a museum than a stock ticker. -

THE PUNISHER WAR JOURNAL by Luis Filipe Based on Marvel Comics

THE PUNISHER THE PUNISHER WARWAR JOURNALJOURNAL by Luis Filipe Based on Marvel Comics character Copyright (c) 2017 This is just a fan made [email protected] OVER BLACK The sound of a POLICE RADIO calling. RADIO All units. Central Park shooting, requiring reinforcements immediately. CUT TO: CELL PHONE POV: Filming towards of Central Park alongside more people. Everyone horrified, but we don't know for what yet. CUT TO: VIDEO FOOTAGE: Now in Central Park where the police and CSI surround an entire area that is filled with CORPSES. A REPORTER talks to the camera. REPORTER Today New York witnessed the biggest outdoor massacre. It is speculated that the victims are members of the Mafia or even gangs, but no confirmation from the police yet. CUT TO: ANOTHER FOOTAGE: With the cameraman zooming in the forensic putting some bodies in black bags. One of them we notice that it's a little girl, and another a woman. REPORTER (O.S.) Apparently there was only one survivor. The victim is in serious condition but the paramedics doubt that he will hold it for long. CUT TO: SHAKY FOOTAGE: The only surviving man being taken on the stretcher to an ambulance. An oxygen mask on his face. His body covered in blood. He still uses his last forces to murmur. MAN My family... I want my... family. He is placed inside the ambulance. As the paramedics slam the ambulance doors - CUT TO BLACK: 2. Then - FADE IN: INT. CASTLE'S APARTMENT - DAY A small place with little furniture. The curtain blocks the sun from the single window of the apartment, allowing only a wispy sunlight to enter. -

Punisher Max: the Complete Collection Vol. 4: Vol

PUNISHER MAX: THE COMPLETE COLLECTION VOL. 4: VOL. 4 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Garth Ennis,Goran Parlov,Howard Chaykin | 544 pages | 27 Dec 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9781302902445 | English | New York, United States Punisher Max: the Complete Collection Vol. 4: Vol. 4 PDF Book But when he's left with six hours to live, that only means he has time to kill! Punisher Vol. Product details Format Paperback pages Dimensions x x Great few series of Punisher but not a big fan of the last one. Please enter a valid email address. Following upon the events in Long Cold Dark , this arc pulls in all the loose plot threads and subplots of Ennis' entire run including the Born mini series, which opened the first of these complete collections , and delivers in an absolutely stunning way. And the only good thing I can say about it is that the great Richard Corben draws it. Appearing in the short-lived but critically-acclaimed British anthology Crisis and illustrated by McCrea, it told the story of a young, apolitical Protestant man caught up by fate in the violence of the Irish 'Troubles'. Another very clear five stars piece to close this truly epic run. There's a good sense of bookends here that marks the end of Ennis' work on the character, I'm interested in seeing where future collections will go following his departure. I loved that he was former special forces and did a few tours in Vietnam. Whatever though I n the waning days of the Vietnam War Learn More. Less a Punisher story and more the author writing out his frustration about how a few rich a-holes control too much of the world. -

Punisher: War Machine Part Three Chernayap, a Rogue State in Eastern Europe, Is Operating Under the Militaryr Regime of General Petrov

220 ROSENBERG VILANOVA LOUGHRIDGE 2 2 0 1 1 PARENTAL ADVISORY $3.99US MARVEL.COM 7 59606 08811 9 MARVEL COMICS PROUDLY PRESENTS: FRANK CASTLE WAS A DECORATED MARINE, AN UPSTANDING CITIZEN, AND A FAMILY MAN. THEN HIS FAMILY WAS TAKEN FROM HIM WHEN THEY WERE ACCIDENTALLY KILLED IN A BRUTAL MOB HIT. FROM THAT DAY, HE BECAME A FORCE OF COLD, CALCULATED RETRIBUTION AND VIGILANTISM. FRANK CASTLE DIED WITH HIS FAMILY. NOW, THERE IS ONLY… THE UNISHEFRANK CASTLE in PUNISHER: WAR MACHINE PART THREE CHERNAYAP, A ROGUE STATE IN EASTERN EUROPE, IS OPERATING UNDER THE MILITARYR REGIME OF GENERAL PETROV. PETROV WAS ABLE TO TAKE POWER USING RESOURCES AND PERSONNEL FROM A FORMER S.H.I.E.L.D. OUTPOST, SET UP IN SECRET BY NICK FURY, THAT WENT SOUR AFTER THE GLOBAL SPY ORGANIZATION WENT UNDER. NICK FURY’S GOT A PROBLEM—FRANK CASTLE IS THE SOLUTION. FURY FILLED CASTLE IN ON THE SITUATION AND LED HIM TO THE HARDWARE THAT’S GOING TO ENABLE HIM TO STAND A CHANCE AGAINST THIS LARGE-SCALE THREAT—THE WAR MACHINE ARMOR! NEWLY EQUIPPED, THE PUNISHER HAS DRAWN FIRST BLOOD AGAINST THE REGIME, BUT THE WAR IS JUST BEGINNING… WRITER... MATTHEW ROSENBERG ARTIST... guiu VILANOVA COLORIST... LEE LOUGHRIDGE LETTERER... VC’s CORY PETIT COVER ARTIST... CLAYTON CRAIN SPECIAL THANKS MITCH MONTGOMERY DESIGNER ANTHONY GAMBINO ASSOCIATE EDITOR MARK BASSO EDITOR JAKE THOMAS EDITOR IN CHIEF C.B. Cebulski CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER JOE QUESADA PRESIDENT DAN BUCKLEY EXECUTIVE PRODUCER ALAN FINE THE PUNISHER No. 220, March 2018. Published Monthly by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC.