Chavs: the Demonization of the Working Class

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections David Hirsh Department of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, UK The Working Papers Series is intended to initiate discussion, debate and discourse on a wide variety of issues as it pertains to the analysis of antisemitism, and to further the study of this subject matter. Please feel free to submit papers to the ISGAP working paper series. Contact the ISGAP Coordinator or the Editor of the Working Paper Series, Charles Asher Small. Working Paper Hirsh 2007 ISSN: 1940-610X © Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy ISGAP 165 East 56th Street, Second floor New York, NY 10022 United States Office Telephone: 212-230-1840 www.isgap.org ABSTRACT This paper aims to disentangle the difficult relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. On one side, antisemitism appears as a pressing contemporary problem, intimately connected to an intensification of hostility to Israel. Opposing accounts downplay the fact of antisemitism and tend to treat the charge as an instrumental attempt to de-legitimize criticism of Israel. I address the central relationship both conceptually and through a number of empirical case studies which lie in the disputed territory between criticism and demonization. The paper focuses on current debates in the British public sphere and in particular on the campaign to boycott Israeli academia. Sociologically the paper seeks to develop a cosmopolitan framework to confront the methodological nationalism of both Zionism and anti-Zionism. It does not assume that exaggerated hostility to Israel is caused by underlying antisemitism but it explores the possibility that antisemitism may be an effect even of some antiracist forms of anti- Zionism. -

National Policy Forum (NPF) Report 2018

REPORT 2018 @LabPolicyForum #NPFConsultation2018 National Policy Forum Report 2018 XX National Policy Forum Report 2018 Contents NPF Elected Officers ....................................................................................................................4 Foreword ........................................................................................................................................5 About this document ...................................................................................................................6 Policy Commission Annual Reports Early Years, Education and Skills ............................................................................................7 Economy, Business and Trade ............................................................................................. 25 Environment, Energy and Culture ....................................................................................... 39 Health and Social Care ........................................................................................................... 55 Housing, Local Government and Transport ..................................................................... 71 International ............................................................................................................................. 83 Justice and Home Affairs ....................................................................................................... 99 Work, Pensions and Equality ..............................................................................................119 -

TUC London, East and South East

TUC London, East and South East Annual report 2018 . About the regional TUC ‘TUC: London East and the South East’ is the largest of the TUC’s regions and geographically we cover three European parliamentary constituencies or what were the government office regions: London, the South East, and East of England. Perhaps as many as two million trade unionists live and work within the region. Our regional council is appointed annually by trade our union affiliates and by county associations of trades councils. It meets four times a year to discuss both how to achieve policy determined at the annual national Trades Union Congress, and to make policies on issues specific to, or affecting, our region. At the regional council’s annual general meeting it elects its officers, and an executive committee that meets ten times a year. The officers and executive committee members serve for a year. Affiliated trade unions and county associations of trades councils also nominate to our industrial and equality sub-groups. These advisory sub-groups use their expertise, workplace and life experience to inform the activities of the regional council. In order to assist in our work fostering and supporting trade unionism in our region outside of London we have created the East of England Trade Union Network, EETUN, and the South East Trade Union Network, SETUN, within the structures of the regional TUC. Regional staff administer the regional council, deliver services to affiliates, represent the TUC in relations with public bodies, campaign for Congress policies, and support the delivery of learning and education to workers in the region. -

Swivel-Eyed Loons Had Found Their Cheerleader at Last: Like Nobody Else, Boris Could Put a Jolly Gloss on Their Ugly Tale of Brexit As Cultural Class- War

DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, MCQs, Magazines www.thecsspoint.com Download CSS Notes Download CSS Books Download CSS Magazines Download CSS MCQs Download CSS Past Papers The CSS Point, Pakistan’s The Best Online FREE Web source for All CSS Aspirants. Email: [email protected] BUY CSS / PMS / NTS & GENERAL KNOWLEDGE BOOKS ONLINE CASH ON DELIVERY ALL OVER PAKISTAN Visit Now: WWW.CSSBOOKS.NET For Oder & Inquiry Call/SMS/WhatsApp 0333 6042057 – 0726 540141 FPSC Model Papers 50th Edition (Latest & Updated) By Imtiaz Shahid Advanced Publishers For Order Call/WhatsApp 03336042057 - 0726540141 CSS Solved Compulsory MCQs From 2000 to 2020 Latest & Updated Order Now Call/SMS 03336042057 - 0726540141 Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power & Peace By Hans Morgenthau FURTHER PRAISE FOR JAMES HAWES ‘Engaging… I suspect I shall remember it for a lifetime’ The Oldie on The Shortest History of Germany ‘Here is Germany as you’ve never known it: a bold thesis; an authoritative sweep and an exhilarating read. Agree or disagree, this is a must for anyone interested in how Germany has come to be the way it is today.’ Professor Karen Leeder, University of Oxford ‘The Shortest History of Germany, a new, must-read book by the writer James Hawes, [recounts] how the so-called limes separating Roman Germany from non-Roman Germany has remained a formative distinction throughout the post-ancient history of the German people.’ Economist.com ‘A daring attempt to remedy the ignorance of the centuries in little over 200 pages... not just an entertaining canter -

00 Muncie 4E BAB1408B0166

00_Muncie_4e_BAB1408B0166_Prelims.indd 3 18-Nov-14 9:13:10 PM 1 Youth Crime: Representations, Discourses and Data Chapter 1 examines: • the concepts of ‘crime’, ‘youth’, ‘criminalization’ and ‘social construction’; • how young people have come to be regarded as a threat; • how the ‘problem of youth’ is frequently collapsed into the problem of crime and disorder; • how young people are represented in media and political discourses; • the reliability of statistical measures of youth offending; • the gendered nature of offending; • the relationship between gangs and violent crime; • the relationship between drug use and criminality. Key terms corporate crime; crime; criminalization; delinquency; demonization; deviance; discourse; folk devil; gang; hidden crime; moral panic; official statistics; protective factors; recording of crime; reporting of crime; representation; risk factors; self-report studies; social con- structionism; status offence; youth This introductory chapter is designed to promote a critical understanding of the relationship between youth and crime. The equation of these two terms is widely employed and for many is accepted as common sense. Stories about youth and crime are a mainstay of most forms of media. Official crime statistics are readily and uncritically recited to substantiate a view that youth crime and disorder are now ‘out of control’. But how far do the media reflect social reality and how much are they able to define it? How valid and reliable is statistical evidence? By asking these questions, the chapter draws attention to how the state of youth and the 01_Muncie_4e_BAB1408B0166_Ch-01.indd 1 11/18/2014 8:40:00 PM problem of crime come to be defined in particular circumscribed ways. -

Theos Turbulentpriests Reform:Layout 1

Turbulent Priests? The Archbishop of Canterbury in contemporary English politics Daniel Gover Theos Friends’ Programme Theos is a public theology think tank which seeks to influence public opinion about the role of faith and belief in society. We were launched in November 2006 with the support of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, and the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O'Connor. We provide • high-quality research, reports and publications; • an events programme; • news, information and analysis to media companies and other opinion formers. We can only do this with your help! Theos Friends receive complimentary copies of all Theos publications, invitations to selected events and monthly email bulletins. If you would like to become a Friend, please detach or photocopy the form below, and send it with a cheque to Theos for £60. Thank you. Yes, I would like to help change public opinion! I enclose a cheque for £60 made payable to Theos. Name Address Postcode Email Tel Data Protection Theos will use your personal data to inform you of its activities. If you prefer not to receive this information please tick here By completing you are consenting to receiving communications by telephone and email. Theos will not pass on your details to any third party. Please return this form to: Theos | 77 Great Peter Street | London | SW1P 2EZ S: 97711: D: 36701: Turbulent Priests? what Theos is Theos is a public theology think tank which exists to undertake research and provide commentary on social and political arrangements. We aim to impact opinion around issues of faith and belief in The Archbishop of Canterbury society. -

Adjudication of Ofcom Content Sanctions Committee

Ofcom Content Sanctions Committee Consideration of sanction against Channel Four Television Corporation in respect of its service Channel 4. 1 For Breaches of the Ofcom Broadcasting Code: • Rule 2.3 – Broadcasters must when applying generally accepted standards ensure that material which may cause offence is justified by the context; and • Rule 1.3 – Children must also be protected by appropriate scheduling from unsuitable material. On 15, 17, 18, 19 January 2007 Decision To direct Channel Four (and S4C) to broadcast a statement of Ofcom’s findings in a form determined by Ofcom immediately before the start of the broadcast of the first programme of the eighth series of Big Brother on Channel 4; immediately before the start of the broadcast of the first re- versioned programme of the eighth series of Big Brother on Channel 4; and immediately before the start of the broadcast of the programme in which the first eviction from the eighth series of Big Brother occurs on Channel 4. 1 This sanction also applies to Sianel Pedwar Cymru (“S4C”) which transmits Channel 4’s (Celebrity) Big Brother series on its service. 1 Contents Section Page 1 Summary 3 2 Background 6 3 Legal Framework 8 4 Issues raised with Channel Four and Channel Four’s Response 12 5 Ofcom’s Adjudication: Introduction 36 6 Not In Breach 42 7 Resolved 55 8 In Breach 57 9 Sanctions Decision 66 2 1 Summary 1.1 On the basis detailed in the Decision, under powers delegated from the Ofcom Board to Ofcom’s Content Sanctions Committee (“the Committee”), the Committee has decided to impose a statutory sanction on Channel Four (and S4C) in light of the serious nature of the failure by Channel Four to ensure compliance with Ofcom’s Broadcasting Code. -

New Peers Created Have Fallen from 244 Under David Cameron’S Six Years As Prime Minister to Only 37 to Date Under Theresa May

\ For more information on DeHavilland and how we can help with political monitoring, custom research and consultancy, contact: +44 (0)20 3033 3870 [email protected] Information Services Ltd 2018 0 www.dehavilland.co.uk INTRODUCTION & ANALYSIS ............................................................................................................. 2 CONSERVATIVES ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Diana Barran MBE .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 The Rt. Hon. Sir Edward Garnier QC ........................................................................................................................... 5 The Rt. Hon. Sir Alan Haselhurst.................................................................................................................................. 7 The Rt. Hon. Peter Lilley ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Catherine Meyer CBE ................................................................................................................................................... 10 The Rt. Hon. Sir Eric Pickles ........................................................................................................................................ 11 The Rt. Hon. Sir John -

Notes and References

Notes and References Introduction 1. Simon Lee, The Cost of Free Speech (London: Faber, 1990) p. ix. 2. The wonderfully judicious and precise phrase ‘adequate to the predicament’ is one of the gifts bequeathed by the late Seamus Heaney, in his collection North. 3. An example is Peter Jones’s otherwise brilliant essay ‘Respecting Beliefs and Rebuking Rushdie’, British Journal of Political Science, 20:4, 1990, pp. 415–37. 4. Andrew Gibson, Postmodernity, Ethics and the Novel: From Leavis to Levinas (London: Routledge, 1999). 5. The phrase ‘civilization-speak’ is Heiko Henkel’s. See his essay, ‘“The journalists of Jyllands-Posten are a bunch of reactionary provocateurs”: The Danish Cartoon Controversy and the Self-Image of Europe,’ Radical Philosophy, 137, 2006, p. 2. 6. Glen Newey, ‘Unlike a Scotch Egg’, London Review of Books, 35:23, 5 December 2013, p. 22. 1 From Blasphemy to Offensiveness: the Politics of Controversy 1. In using the term ‘the Rushdie affair’ as a shorthand for the controversy over The Satanic Verses, I concur with Paul Weller who notes the Muslim objections to it on the grounds that it seemingly trivialized what was, in fact, an event of momentous significance. It does retain, however, a certain currency even now and was the dominant marker at the time, used in many documents and sources that I will have occasion to quote. I will therefore use it alongside other descriptive terminol- ogy such as ‘The Satanic Verses controversy’. 2. Paul Weller, A Mirror for Our Times: ‘The Rushdie Affair’ and the Future of Multiculturalism (London: Continuum, 2009). -

175359 Orig.Pdf

Dictionary of Media Studies Specialist dictionaries Dictionary of Accounting 0 7475 6991 6 Dictionary of Aviation 0 7475 7219 4 Dictionary of Banking and Finance 0 7136 7739 2 Dictionary of Business 0 7475 6980 0 Dictionary of Computing 0 7475 6622 4 Dictionary of Economics 0 7475 6632 1 Dictionary of Environment and Ecology 0 7475 7201 1 Dictionary of Human Resources and Personnel Management 0 7475 6623 2 Dictionary of ICT 0 7475 6990 8 Dictionary of Information and Library Management 0 7136 7591 8 Dictionary of Law 0 7475 6636 4 Dictionary of Leisure, Travel and Tourism 0 7475 7222 4 Dictionary of Marketing 0 7475 6621 6 Dictionary of Medical Terms 0 7136 7603 5 Dictionary of Military Terms 0 7475 7477 4 Dictionary of Nursing 0 7475 6634 8 Dictionary of Politics and Government 0 7475 7220 8 Dictionary of Science and Technology 0 7475 6620 8 Easier English™ titles Easier English Basic Dictionary 0 7475 6644 5 Easier English Basic Synonyms 0 7475 6979 7 Easier English Dictionary: Handy Pocket Edition 0 7475 6625 9 Easier English Intermediate Dictionary 0 7475 6989 4 Easier English Student Dictionary 0 7475 6624 0 English Thesaurus for Students 1 9016 5931 3 Check Your English Vocabulary workbooks Academic English 0 7475 6691 7 Business 0 7475 6626 7 Computing 1 9016 5928 3 Human Resources 0 7475 6997 5 Law 0 7136 7592 6 Leisure, Travel and Tourism 0 7475 6996 7 FCE + 0 7475 6981 9 IELTS 0 7136 7604 3 PET 0 7475 6627 5 TOEFL® 0 7475 6984 3 TOEIC 0 7136 7508 X Visit our website for full details of all our books: www.acblack.com Dictionary of Media Studies A & C Black ț London www.acblack.com First published in Great Britain in 2006 A & C Black Publishers Ltd 38 Soho Square, London W1D 3HB © A & C Black Publishers Ltd 2006 All rights reserved. -

MINUTES and RECORD of the EXECUTIVE

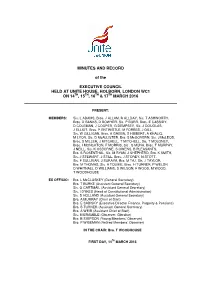

MINUTES AND RECORD of the EXECUTIVE COUNCIL HELD AT UNITE HOUSE, HOLBORN, LONDON WC1 ON 14 TH , 15 TH , 16 TH & 17 TH MARCH 2016 PRESENT: MEMBERS: Sis. L ADAMS, Bros. J ALLAM, R ALLDAY, Sis. T ASHWORTH, Bros. D BANKS, D BOWYER, Sis. P BURR, Bros. E CASSIDY, D COLEMAN, J COOPER, G DEMPSEY, Sis. J DOUGLAS, J ELLIOT, Bros. P ENTWISTLE, M FORBES, J GILL, Sis. W GILLIGAN, Bros. A GREEN, S HIBBERT, A KHALIQ, M LYON, Sis. D McALLISTER, Bro. S McGOVERN, Sis. J McLEOD, Bros. S MILLER, J MITCHELL, T MITCHELL, Sis. T MOLONEY, Bros. I MONCKTON, F MORRIS, Sis . S MUNA, Bros. T MURPHY, J NEILL, Sis. K OSBORNE, S OWENS, B PLEASANTS, Bro. S ROSENTHAL, Sis. M RYAN, J SHEPHERD, Bro. K SMITH, Sis. J STEWART, J STILL, Bros. J STOREY, N STOTT, Sis. F SULLIVAN, J SURAYA, Bro. M TAJ, Sis. J TAYLOR, Bro. M THOMAS, Sis. A TOLMIE, Bros. H TURNER, P WELSH, D WHITNALL, D WILLIAMS, D WILSON, F WOOD, M WOOD, T WOODHOUSE EX OFFICIO: Bro. L McCLUSKEY (General Secretary) Bro. T BURKE (Assistant General Secretary) Sis. G CARTMAIL (Assistant General Secretary) Sis. I DYKES (Head of Constitutional Administration) Sis. D HOLLAND (Assistant General Secretary) Bro. A MURRAY (Chief of Staff) Bro. E SABISKY (Executive Director Finance, Property & Pensions) Bro. S TURNER (Assistant General Secretary) Bro. A WEIR (Assistant Chief of Staff) Sis. M BRAMBLE (Observer, Gibraltar) Bro. B SIMPSON (Young Members’ Observer) Bro. P WISEMAN (Retired Members’ Observer) IN THE CHAIR: Bro. T WOODHOUSE FIRST DAY, 14 TH MARCH 2016 ____________________________ EXECUTIVE COUNCIL MARCH 2016 The Chair welcomed the newly elected Territorial Representative from Scotland, Eddie Cassidy to the Executive Council. -

Carina Trimingham -V

Neutral Citation Number: [2012] EWHC 1296 (QB) Case No: HQ10D03060 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 24/05/2012 Before: THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE TUGENDHAT - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between: Carina Trimingham Claimant - and - Associated Newspapers Limited Defendant - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Matthew Ryder QC & William Bennett (instructed by Mishcon de Reya) for the Claimant Antony White QC & Alexandra Marzec (instructed by Reynolds Porter Chamberlain LLP) for the Defendant Hearing dates: 23,24,25,26,27 April 2012 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment I direct that pursuant to CPR PD 39A para 6.1 no official shorthand note shall be taken of this Judgment and that copies of this version as handed down may be treated as authentic. ............................. THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE TUGENDHAT THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE TUGENDHAT Trimingham v. ANL Approved Judgment Mr Justice Tugendhat : 1. By claim form issued on 11 August 2010 the Claimant (“Ms Trimingham”) complained that the Defendant had wrongfully published private information concerning herself in eight articles. 2. Mr Christopher Huhne MP had been re-elected as the Member of Parliament for Eastleigh in Hampshire at the General Election held in May 2010, just over a month before the first of the articles complained of. He became Secretary of State for Energy in the Coalition Government. He was one of the leading figures in the Government and in the Liberal Democrat Party. In 2008 Ms Trimingham and Mr Huhne started an affair, unknown to both Mr Huhne’s wife, Ms Pryce, and Ms Trimingham’s civil partner. By 2008 Mr Huhne had become the Home Affairs spokesman for the Liberal Democrats.