Syrian Spillover National Tensions, Domestic Responses, & International Options

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Detailed Itinerary

Detailed Itinerary Trip Name: [10 days] People & Landscapes of Lebanon GENERAL Dates: This small-group trip is offered on the following fixed departure dates: October 29th – November 7th, 2021 February 4th – Sunday 13th, 2022 April 15th – April 24th, 2022 October 28th – November 6th, 2022 Prefer a privatized tour? Contact Yūgen Earthside. This adventure captures all the must-see destinations that Lebanon has to offer, whilst incorporating some short walks along the Lebanon Mountain Trail (LMT) through cedar forests, the Chouf Mountains and the Qadisha Valley; to also experience the sights, sounds and smells of this beautiful country on foot. Main Stops: Beirut – Sidon – Tyre – Jezzine – Beit el Din Palace – Beqaa Valley – Baalbek – Qadisha Valley – Byblos © Yūgen Earthside – All Rights Reserved – 2021 - 1 - About the Tour: We design travel for the modern-day explorer by planning small-group adventures to exceptional destinations. We offer a mixture of trekking holidays and cultural tours, so you will always find an adventure to suit you. We always use local guides and teams, and never have more than 12 clients in a group. Travelling responsibly and supporting local communities, we are small enough to tread lightly, but big enough to make a difference. DAY BY DAY ITINERARY Day 1: Beirut [Lebanon] (arrival day) With group members arriving during the afternoon and evening, today is a 'free' day for you to arrive, be transferred to the start hotel, and to shake off any travel fatigue, before the start of your adventure in earnest, tomorrow. Accommodation: Hotel Day 2: Beirut City Tour After breakfast and a welcome briefing, your adventure begins with a tour of this vibrant city, located on a peninsula at the midpoint of Lebanon’s Mediterranean coast. -

Chapter 4 Assessment of the Tourism Sector

The Study on the Integrated Tourism Development Plan in the Republic of Lebanon Final Report Vol. 4 Sector Review Report Chapter 4 Assessment of the Tourism Sector 4.1 Competitiveness This section uses the well-known Strengths-Weaknesses-Opportunities-Threats [SWOT] approach to evaluate the competitiveness of Lebanon for distinct types of tourism, and to provide a logical basis for key measures to be recommended to strengthen the sector. The three tables appearing in this section summarize the characteristics of nine segments of demand that Lebanon is attracting and together present a SWOT analysis for each to determine their strategic importance. The first table matches segments with their geographic origin. The second shows characteristics of the segments. Although the Diaspora is first included as a geographic origin, in the two later tables it is listed [as a column] alongside the segments in order to show a profile of its characteristics. The third table presents a SWOT analysis for each segment. 4.1.1 Strengths The strengths generally focus on certain strong and unique characteristics that Lebanon enjoys building its appeal for the nine segments. The country’s mixture of socio-cultural assets including its built heritage and living traditions constitutes a major strength for cultural tourism, and secondarily for MICE segment [which seeks interesting excursions], and for the nature-based markets [which combines nature and culture]. For the Diaspora, Lebanon is the unique homeland and is unrivaled in that role. The country’s moderate Mediterranean climate is a strong factor for the vacationing families coming from the hotter GCC countries. -

A Two-Year Survey on Mosquitoes of Lebanon Knio K.M.*, Markarian N.*, Kassis A.* & Nuwayri-Salti N.**

Article available at http://www.parasite-journal.org or http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/parasite/2005123229 A TWO-YEAR SURVEY ON MOSQUITOES OF LEBANON KNIO K.M.*, MARKARIAN N.*, KASSIS A.* & NUWAYRI-SALTI N.** Summary: Résumé : LES MOUSTIQUES DU LIBAN : RÉSULTATS DE DEUX ANS DE RÉCOLTES A total of 6,500 mosquitoes were identified during a two-year survey (1999-2001) in Lebanon, and these belonged to twelve Au cours d’une période d’observation de deux ans (1999-2001), species: Culex pipiens, Cx. laticinctus, Cx. mimeticus, 6500 moustiques ont été identifiés au Liban et répartis en Cx. hortensis, Cx. judaicus, Aedes aegypti, Ae. cretinus, 12 espèces : Culex pipiens, Cx. laticinctus, Cx. mimeticus, Ochlerotatus caspius, Oc. geniculatus, Oc. pulchritarsis, Culiseta Cx. hortensis, Cx. judaicus, Aedes aegypti, Ae. cretinus, longiareolata and Anopheles claviger. Culex pipiens was the most Ochlerotatus caspius, Oc. geniculatus, Oc. pulchritarsis, Culiseta predominant species in Lebanon, collected indoors and outdoors. longiareolata and Anopheles claviger. Culex pipiens, l’espèce It was continuously abundant and active throughout the year. prédominante, a été collectée à l’extérieur et à l’intérieur. Elle a Culex judaicus was a small and rare mosquito and it is reported été trouvée abondante et active tout au long de l’année. Culex to occur for the first time in Lebanon. On the coastal areas, judaicus, espèce petite et rare, a été observée et identifiée pour Ochlerotatus caspius was very common, and proved to be a la première fois au Liban. Dans les zones côtières, il s’est avéré complex of species as two forms were detected. -

TOURISM in HEZBOLLAND with the War in Syria, The

Tourism in Hezbolland ERIC LAFFORGUE With the war in Syria, the entire Lebanese border has become a red area which Western governments warn against all travel to. But on the ground, only a few military checkpoints remind the rare traveler that tensions are running high in the region as life goes on. Hezbollah (the Party of God) rules in the Beqaa Valley. It is a Shia Islamist political, military and social organisation which has become powerful in Lebanon and is represented in the government and the Parliament. Hezbollah is called a terrorist organisation by Western states, Israel, Arab Gulf states and the Arab League. It now controls areas that are home to UNESCO World Heritage sites and has built a museum that glorifies the war against Israel. In the Beqaa Valley, Machghara village greets you with portraits of Iranian leaders and Hezbollah martyrs. Hezbollah relies on the military and financial support of Shia Iran. F o r t h o s e w h o d o n ’t f o l l o w geopolitics, it is easy to guess who Hezbollah’s friends are just by looking at signs in the streets or the DVDs for sale in local shops: Syria’s Bashar Al Assad and the Iranian leaders. The UNESCO listed Temple of Bacchus in Baalbek is now deserted. For years, its festival saw the likes of international stars such as Miles Davis, Sting, Deep Purple, or Joan Baez… During the Second Lebanon War, Israel dropped 70 bombs on Baalbek but the Roman ruins show only very little damage. -

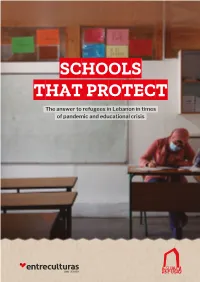

Schools That Protect

SCHOOLS THAT PROTECT The answer to refugees in Lebanon in times of pandemic and educational crisis 1 Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Duis at commodo lacus. Nunc commodo a enim eu efficitur. Sed laoreet neque id orci dapibus vestibulum in nec est. Proin aliquet, lorem a facilisis cursus, libero turpis blandit tellus, ac dignissim ipsum enim et lorem. INDEX OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Syria, a unending decade of conflict. 3. Lebanon, immersed in a crisis that affects the Lebanese population and the refugees. 4. Education in Lebanon and Syria. The difficulties in getting a quality education. 5. The change from the classrooms to learning over the telephone in the schools of the JRS in Beqaa. 6. The impact of the transition to on-line education. 7. Conclusions. 8. Recommendations. 9. Bibliography. 1 1. INTRODUCTION Ten years of civil war in Syria have forced more than 13 million people to leave their homes; half of them have had to flee to other countries. Lebanon, mired in a serious multi-causal crisis and with a total population of 6,8 million, is home to 1,5 million Syrians, making it the state hosting the largest number of refugees per capita in the world. According to UNHCR1, 39% of the registered refugee population in Lebanon is concentrated in the Beqaa Valley 30 kilometres from the capital, Beirut, although there are likely to be many more unregistered Syrian households. It is in this region where the ratio of Lebanese citizens to Syrian refugees is now two to one. Part of the refugee population is concentrated in cities such as Baalbek and Bar Elias; however, a large number of families live poorly in makeshift and informal camps, increasing their vulnerability to bad weather, disease and lack of protection. -

NIHA مسار الفينيقيني the PHOENICIANS' ROUTE نيحا INTRODUCTION Niha Is a Small Village Located in the Beqaa Valley

NIHA مسار الفينيقيني THE PHOENICIANS' ROUTE نيحا INTRODUCTION Niha is a small village located in the Beqaa Valley. It is situated 65 Km East of the capital Beirut, 8 Km north of Zahle, 2 Km north East of the city of Ablah and 29 Km away from the touristic city of Baalbek. At the West of the village, Ferzol; rich in agricultural lands and archaeological sites as well as Nabi Ayla where the prophet Elia is buried. At the South of the village “Ablah”, where the most important military base in the Beqaa is found. On the East side, Tammine; characterized by an important concentration of the Shiia community as well as a big concentration of commercial activities and finally on the north side, Sannine; the western Lebanese mountain chain. The only access to the village is a secondary road that turns around itself, creating a quite intimate, private and calm atmosphere for the village away from any noise pollution or vehicular traffic. HISTORICAL MAPPING The Small Roman Temple (1) Approximate Plan The Rule of 9 Steps The Upper Grand Temple is built 2 Km away from the village of Niha at an altitude of 1400 meters. It is accessible by a recently renovated road though. The temple itself is not restored. Archi- tectural findings suggest that the temple was transformed into a fortress during the Medieval times which is why this area is called today Hosn. The Temple was built on a podium facing East. Upper Grand Roman Temple (2) The Big Roman Temple (1) The Big Roman Temple Map of Niha Scale 1/500 Approximate Elevation Reconstruction and Plan Legend The Romans excavated Greek - Roman Period 333 B.C. -

(LCRP 2017-2020) 2018 Results

SUPPORT TO PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS IN LEBANON UNDER THE LEBANON CRISIS RESPONSE PLAN (LCRP 2017-2020) 2018 RESULTS 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 SUPPORT TO SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS 4 SUPPORT TO EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS 9 SUPPORT TO PUBLIC HEALTH INSTITUTIONS 15 SUPPORT TO ENERGY AND WATER INSTITUTIONS 21 SUPPORT TO MUNICIPALITIES AND UNIONS 27 SUPPORT TO AGRICULTURE INSTITUTIONS 33 SUPPORT TO OTHER INSTITUTIONS 35 Cover Photo: Rana Sweidan, UNDP 2018 AFP Acute Flaccid Paralysis PSS Psychosocial support ALP Accelerated Learning Programme RACE Reach All Children with Education AMR Antimicrobial resistance RH Reproductive Health BMLWE Beirut and Mt Lebanon Water Establishment SARI Severe acute respiratory infection BWE Bekaa Water Establishment SDC Social Development Center CB-ECE Community-Based Early Childhood Education SGBV Sexual and Gender-Based Violence CBRN Chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear SLWE South Lebanon Water Establishment CERD Curriculum Development, Training and Research SOP Standard Operating Procedures CoC Codes of Conduct TOT Training of Trainers CSO Civil Society Organization TTCM Teacher Training Curriculum Model cVDPV Circulating vaccine derived poliovirus TVET Technical and Vocational Education and Training DG Directorate General UN United Nations DOPS Department of scholar pedagogy UNDP United Nations Development Program ECL Education Community Liaisons UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees EdL Electricite du Liban UNICEF United Nations International Children's Fund EIA/SEA Environmental -

OF LEBANON: WHAT WIKILEAKS TELLS US ABOUT AMERICAN EFFORTS to FIND an ALTERNATIVE to HIZBALLAH December 22, 2011 Gloria-Center.Org

http://www.gloria-center.org/2011/12/the-%e2%80%9cindependent-shi%e2%80%99a%e2%80%9d-of-lebanon-what-wikileaks-tells-us-about-american-efforts-to-find-an-alternative-to-hizballah/ THE “INDEPENDENT SHI’A” OF LEBANON: WHAT WIKILEAKS TELLS US ABOUT AMERICAN EFFORTS TO FIND AN ALTERNATIVE TO HIZBALLAH December 22, 2011 gloria-center.org By Phillip Smyth U.S. diplomatic cables released by Wikileaks have given a new insight into American policy in Lebanon, especially efforts to counter Hizballah. Hizballah’s willingness to use a combination of hard power through violence and coercion, combined with a softer touch via extensive patronage networks has given them unmatched control over the Shi’a community since the 2005 Cedar Revolution. Using these released cables, this study will focus on efforts, successes, and failures made by so-called “independent” Shi’i political organizations, religious groups, and NGOs to counter Hizballah’s pervasive influence among Lebanon’s Shi’a. I sat in on a fascinating meeting yesterday with some independent Shia Muslims – that is to say, Shias who are trying to fight against Hezbollah’s influence in Lebanon. They’re an admirable group of people, really on the front lines of history in a pretty gripping way… To make a long story short, the March 14 coalition pretty much screwed them… However: you know how everyone says Lebanon is so complicated? Well, it is, but once you understand a few basic particulars on why things are structured as they are, it’s really not so different from other places. – Michael Tomasky, American journalist, March 13, 2009.[1] INTRODUCTION Leaked cables emanating from Wikileaks have provided a unique insight into a realm of U.S. -

Together Yet Apart. the Institutional Rift Among Lebanese-Muslims in A

Jahrbuch für Geschichte Lateinamerikas Anuario de Historia de América Latina 56 | 2019 | 97-121 Omri Elmaleh Tel Aviv University Together Yet Apart The Institutional Rift Among Lebanese- Muslims in a South American Triple Frontier and Its Origins Except where otherwise noted, this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0) https://doi.org/10.15460/jbla.56.143 Together Yet Apart The Institutional Rift Among Lebanese-Muslims in a South American Triple Frontier and Its Origins Omri Elmaleh Abstract. - On October 1988, the first mosque in the Triple Frontier between Argentina-Brazil-Paraguay was inaugurated. The name given to the mosque rekindled old and modern disputes amongst local Lebanese-Muslims in the region and led to the creation of parallel religious and cultural institutions. Based on oral history and local press,1 the article illustrates how the inauguration of the mosque and its aftermath reflected an Islamic dissension and Lebanese inter-religious and ethnic tensions that were "exported" to the Triple Frontier during the 1980s. The article also argues that the sectarian split among the leadership of the organized community, was not shared by the rank and file and did not reflect their daily practices. Keywords: Organized Community, Lebanese Civil War, Sunni-Shiite Schism, Transnationalism, Diaspora. Resumen. - En octubre de 1988 se inauguró la primera mezquita en la Triple Frontera entre Argentina, Brasil y Paraguay, cuyo nombre despertó disputas antiguas entre los distintos miembros de la comunidad libanesa musulmana de la región, lo que finalmente derivó en la creación de instituciones culturales y religiosas paralelas. -

Disability in Syria

Helpdesk Report Disability in Syria Stephen Thompson Institute of Development Studies 08. 03. 2017 Question Carry out a quick needs assessment/mapping of the extent and types of disability issues (physical and mental) that are most prevalent in different regions across Syria amongst men, women, boys and girls. What are donors/UN are doing with regards to disability in Syria? Contents Overview Background to disability and the Syria crisis Disability prevalence in Syria What are donors doing with regards to disability in Syria? What are the UN doing with regards to disability in Syria? What are NGOs doing with regards to disability in Syria? References 1. Overview This rapid review is based on 5 days of desk-based research. It is designed to provide a brief overview of the key issues, and a summary of pertinent evidence found within the time permitted. The literature was identified using two methods. Firstly, a number of experts were identified and contacted. They were asked to provide comments, references and information relevant to this query. Their comments are listed under the ‘Comments from Experts’ section. Secondly, a non- systematic internet based search was undertaken find evidence on disability in Syria There are five main sections to the report. The first main section provides some background information to disability and the Syria crisis. The second looks at disability prevalence in Syria. The third provides information on what the major donors are doing to address disability in Syria. The fourth looks at the contribution of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF). -

The Hariri Assassination and the Making of a Usable Past for Lebanon

LOCKED IN TIME ?: THE HARIRI ASSASSINATION AND THE MAKING OF A USABLE PAST FOR LEBANON Jonathan Herny van Melle A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2009 Committee: Dr. Sridevi Menon, Advisor Dr. Neil A. Englehart ii ABSTRACT Dr. Sridevi Menon, Advisor Why is it that on one hand Lebanon is represented as the “Switzerland of the Middle East,” a progressive and prosperous country, and its capital Beirut as the “Paris of the Middle East,” while on the other hand, Lebanon and Beirut are represented as sites of violence, danger, and state failure? Furthermore, why is it that the latter representation is currently the pervasive image of Lebanon? This thesis examines these competing images of Lebanon by focusing on Lebanon’s past and the ways in which various “pasts” have been used to explain the realities confronting Lebanon. To understand the contexts that frame the two different representations of Lebanon I analyze several key periods and events in Lebanon’s history that have contributed to these representations. I examine the ways in which the representation of Lebanon and Beirut as sites of violence have been shaped by the long period of civil war (1975-1990) whereas an alternate image of a cosmopolitan Lebanon emerges during the period of reconstruction and economic revival as well as relative peace between 1990 and 2005. In juxtaposing the civil war and the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri in Beirut on February 14, 2005, I point to the resilience of Lebanon’s civil war past in shaping both Lebanese and Western memories and understandings of the Lebanese state. -

Feudalism in the Age of Neoliberalism: a Century of Urban and Rural Co-Dependency in Lebanon

Berkeley Planning Journal 31 50 Feudalism in the Age of Neoliberalism: A Century of Urban and Rural Co-dependency in Lebanon ANAHID ZARIG SIMITIAN Abstract The urban and rural co-dependency in Lebanon has been drastically transformed and further heightened since the joining of both territories with the Declaration of Greater Lebanon on September 1st, 1920. The lack of any formal planning during the past century has driven socio-political and economic forces to shape or disfigure the built environment. Historians, geographers, and urban planners have addressed Lebanon’s urban-rural divide by highlighting unequal development. Even still, a comprehensive overview of key historical moments that investigates migrations and the economic system is needed to understand the current co-dependent and conflicted relationship between both territories. Accordingly, this paper explores the urban and rural dynamics starting from the early nineteenth century to modern- day Lebanon, by juxtaposing the flow of migrations between Mount Lebanon and Beirut with the country’s neoliberal economic policies. This analysis is derived from historical books, articles, and theses on the region and aims to highlight the integration of the rural feudalist- sectarian structure with the hyper-financialized urban neoliberal system. Keywords: Beirut, Mount Lebanon, Migrations, Neoliberalism, Feudalism Introduction A century since the establishment of modern Lebanon, the Middle Eastern country by the Mediterranean has yet to witness a comprehensive planning of both its urban and rural territories. The lack of formal planning has allowed sociopolitical and economic forces to take hold of and morph the built environment. Accordingly, the urban-rural divide in Lebanon highlights a context where the absence of state development initia- tives has allowed migrations and the banking system, through the influx of people and the flow of capital, to merge both territories into a co-dependent entity.