The Evil Eye: Preventiion, Detection, Remov Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lone Star Park Race Recap

Lone Star Park Race Recap 2018 Quarter Horse Season Day 13 of 16 Friday, November 2, 2018 Track: Fast, (Clear, 74º) Breeders’ Cup # Winner Jockey Trainer Dis Time SI Mar Paid Second Third 1. 1-Rock On Zoomer V. Aquino (1) L. R. Jordan (2) 550 27.623 97 nose $13.40 6-Geh Ottyes Lil Tini* 2-Perry Delightful 2. 3-Jess a Boy C. Aguilar (9) J. Mejia (4) 300 15.577 92 1 $16.80 1-Pirates Code* 4-Crying Eagle 3. 3-Th Thomas Leo C. Aguilar (10) G. Aguirre, III (2) 870 46.499 89 neck $8.80 2-Hoshi No Senshi* 1-Joxer Daly 4. 5-Slp Mighty High A. Zuniga (11) P. Young (5) 350 17.744 93 neck $9.00 6-Jess Strekin Spunky* 1-Th Maverick 5. 8-Mr Unsung Hero* F. Calderon (10) L. Bard (10) 550 27.200 105 2 ½ $5.00 1-Love Ta Zoom 5-Truly Heroic 6. 3-Bileve E. Ibarra (1) X. Alonzo (2) 330 16.599 102 ½ $9.80 4-Poise N Courage* 2-Big Tex 7. 2-The Flying Dutchman J. Yoakum (4) J. Yoakum (3) 440 22.285 80 2 ¾ $8.40 9-Sweet Yess Fly 3-Ptalleyesonme* 8. 3-Giorgina Sarpresa R. Huerta (4) M. Roman (1) 550 28.229 86 ¾ $7.80 10-Bode Dash 6-Say Yes to the Jess* 9. 2-Jarscartel F. Mendez (3) J. Mendez (1) 220 12.273 83 neck $23.60 4-Bibbity Bobbity Bok 3-Dashing Shiney Penny 10. 5-Skirts Jess Flying N. -

Penny Arcade: Volume 8: Magical Kids in Danger PDF Book

PENNY ARCADE: VOLUME 8: MAGICAL KIDS IN DANGER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mike Krahulik,Jerry Holkins | 112 pages | 11 Sep 2012 | Oni Press,US | 9781620100066 | English | Portland, United States Penny Arcade: Volume 8: Magical Kids in Danger PDF Book The wares of the poor little match girl illuminate her cold world, bringing some beauty to her brief, tragic life. He has a fascination with unicorns , a secret love of Barbies , is a dedicated fan of Spider-Man and Star Wars , and has proclaimed " Jessie's Girl " to be the greatest song of all time. Thompson proceeded to phone Krahulik, as related by Holkins in the corresponding news post. The transformation of humanity through nano… More. PC Gamer. Jul 09, Kevin Gentilcore rated it really liked it. Anyway, people probably already know whether or not they like Penny Arcade. Retrieved March 23, Retrieved May 10, Unless you are a major geek like me, you have no idea what Penny Arcade is. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 26, Retrieved May 9, The comics are from , the commentary from , and both are reflecting an industry that moves rapidly, so both are often unintentionally humorous just in regards to how things have fallen out since. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. He has just enough fuel to reach the planet—then he finds that he has a sto… More. Some of these works have been included with the distribution of the game, and others have appeared on pre-launch official websites. Good collection, quick read. Published September 11th by Oni Press first published August 29th Want to Read Currently Reading Read. -

A Short History of the Lincoln Penny

Read the passage. Then answer the question below. A Short History of the Lincoln Penny Few objects are more common than the Lincoln penny. On any given day, you probably have a few in your pocket or purse. The typical household in the United States has hundreds of pennies squirreled away in piggy banks, jars, and drawers. Everyone is familiar with the penny, but few people ever look at it closely or know much about its history. When the Lincoln penny made its appearance in 1909, it was the first American coin to show the portrait of a historical person. A few coins, such as the Indian Head penny and the Buffalo nickel, had portrayed anonymous Native Americans. Americans, however, had always opposed using coins to honor historical figures. The strong desire to celebrate Abraham Lincoln’s 100th birthday overcame this sentiment. Victor D. Brenner, a Chicago sculptor, contributed the design for the Lincoln penny. His simple, somewhat stark portrait of Lincoln was topped with the words, “In God We Trust.” This was the first time these words appeared on a penny. The word “Liberty,” as mandated by a law passed by Congress, appears to the left of Lincoln, and the date is on his right. Brenner’s initials—VDB—appeared under the date on the first coins. After the coin was released, however, Americans complained that the initials were too large and detracted from the overall design of the penny. So the U.S. Mint removed the initials. As a result, pennies made in 1909 are highly prized by rare coin collectors. -

KNIFE SUPERSTITIONS by LRV 2007 I Was Raised by My Grandparents and Was Always Interested in Their Superstitions

KNIFE SUPERSTITIONS By LRV 2007 I was raised by my grandparents and was always interested in their superstitions. Many of these were based on safety and I found were really an easier way to remember not to do something. Walk under a ladder, open an umbrella in the house, walk behind a horse etc all seemed to make some sense. One of these superstitions was always interesting to me. My grandfather being from the “Old Country” had many superstitions but never handing a knife directly to someone always seemed a little strange to me. He would always put a knife down on the table or desk and allow me or others to take it from there. It wasn’t until recently that I discovered that other than for safety reasons there were other superstitions out there relating to knives. This is a collection of what I’ve been able to find. Some are very similar to one another but different enough that I thought they were interesting. The most common by far was exchanging a gift knife for a penny. Giving a knife as a gift • A knife as a gift from a lover means that the love will soon end. • If a friend gives you a knife, you should give him a coin, or your friendship will soon be broken. • Never give a knife as a housewarming present, or your new neighbor will become an enemy. • To make a present of a knife or any other sharp instrument unless you receive something in exchange. • Giving a knife as a gift you should tape a penny to it so as to not severe the relationship. -

Insights from Wildfire Science: a Resource for Fire Policy Discussions

Insights from wildfire science: A resource for fire policy discussions January 2016 Tania Schoennagel1, Penny Morgan2, Jennifer Balch1, Philip Dennison3, Brian Harvey1, Richard Hutto4, Meg Krawchuk5, Max Moritz6, Ray Rasker7, and Cathy Whitlock8 1University of Colorado-Boulder, 2University of Idaho, 3University of Utah, 4University of Montana, 5Oregon State University, 6University of California-Berkeley, 7Headwaters Economics, 8Montana State University Authors: http://headwaterseconomics.org/wphw/wp-content/uploads/wildfire-insights- authors.pdf [KEYWORDS: forests, shrublands, wildfire, climate change, fire management, fuel reduction treatments, prescribed fire, restoration, fire-adapted, bark beetles, land-use planning, fire- adapted communities] Record blazes swept across parts of the US in 2015, burning more than 10 million acres. The four biggest fire seasons since 1960 have all occurred in the last 10 years, leading to fears of a ‘new normal’ for wildfire. Fire fighters and forest managers are overwhelmed, and it is clear that the policy and management approaches of the past will not suffice under this new era of western wildfires. In recent decades, state and federal policymakers, tribes, and others are confronting longer fire seasons (Jolly et al. 2015), more large fires (Dennison et al. 2014), a tripling of homes burned, and a doubling of firefighter deaths (Rasker 2015). Federal agencies now spend $2 to $3 billion annually fighting fires (and in the case of the US Forest Service, over 50% of their budget), and the total cost to society may be up to 30 times more than the direct cost of firefighting. If we want to contain these costs and reduce risks to communities, economies, and natural systems, we can draw on the best available science when designing fire management strategies, as called for in the recent federal report on Wildland Fire Science and Technology. -

Wildland Fire in Ecosystems: Effects of Fire on Fauna

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Ecosystems Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 1 Effects of Fire on Fauna January 2000 Abstract _____________________________________ Smith, Jane Kapler, ed. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 83 p. Fires affect animals mainly through effects on their habitat. Fires often cause short-term increases in wildlife foods that contribute to increases in populations of some animals. These increases are moderated by the animals’ ability to thrive in the altered, often simplified, structure of the postfire environment. The extent of fire effects on animal communities generally depends on the extent of change in habitat structure and species composition caused by fire. Stand-replacement fires usually cause greater changes in the faunal communities of forests than in those of grasslands. Within forests, stand- replacement fires usually alter the animal community more dramatically than understory fires. Animal species are adapted to survive the pattern of fire frequency, season, size, severity, and uniformity that characterized their habitat in presettlement times. When fire frequency increases or decreases substantially or fire severity changes from presettlement patterns, habitat for many animal species declines. Keywords: fire effects, fire management, fire regime, habitat, succession, wildlife The volumes in “The Rainbow Series” will be published during the year 2000. To order, check the box or boxes below, fill in the address form, and send to the mailing address listed below. -

Louise Penny's August Newsletter

04/01/2016 Louise Penny Newsletter To view this email with images click here Louise Penny's August Newsletter Dear First name Bury your Dead US Edition "She is too fond of books and it has addled her brains" Louisa Mae Alcott This months quote comes from Timothy & Mildred Hanrahant I hope you're having a wonderful summer...we're enjoying the most splendid one in years, in every way. We're harvesting peas and broccoli from the vegetable garden, raspberries are growing wild around the pond where we fight the birds and deer and bears for them. We are not often the winners. And great trees of Stargazer and Casablanca Oriental Lilies are up in the perennial gardens, perfuming our home. Above is a picture Michael took of our screen porch two days ago. Our health is great Michael's eyes as clear and bright as ever. His back is giving some trouble, but whose isn't? And my health is great Click if you wish to preorder too. We have some friends, as I suspect you do too, who are Barnes & Noble.com struggling with ill health, and it certainly makes us aware how lucky Amazon.com we are! But it's the weather that's been the most wonderful sunny ABA American and hot. We don't have air conditioning so some nights are difficult Booksellers Association to sleep but we live on the porch. And pinch ourselves (and sometimes each other) at how lucky we are to live here in Quebec. But I'm sure you feel the same way about your home. -

Penny Infographic

pennies WHAT IS THE COMPOSITION OF A PENNY? Did you know that pennies in the United States have been made from a variety of materials, other than copper? In the past, pennies were made of 100% copper and even steel, but pennies made in 1982 and later are copper-plated zinc. There also have been pennies containing various metallic mixtures of copper with other metals, such as nickel, tin and zinc. CURRENT COMPOSITION OF THE PENNY 97.5% 2.5% ZINC COPPER Zinc 30 Copper 29 Zn Cu 65.38 133 63.546 128 7.14 2 8.92 2,1 [Ar]3d104s2 [Ar]3d104s1 1183 2845 692.7 1358 2020 FUN FACTS ABOUT PENNIES 1965 The first penny, minted in 1793, was as big as a half CURRENTLY PENNIES ARE 1 dollar. That is why it was MADE OF COPPER-PLATED ZINC. called “large cent.” Once it was hard to tell a penny from a dime. During WWII, pennies were made of COPPER 2 silvery-colored steel making it easy to mistake a penny for a dime. Heads, it’s Lincoln; tails, it’s Lincoln. The Lincoln ZINC Memorial cent featured this beloved president on 3 both sides of the coin. One side has his face in profile; the other side has him seated in the Lincoln Memorial. In 1982, more Lincoln cents were minted than in any other year. 16.7 billion pennies were made, 4 which equals $167 million worth of pennies. REFERENCES www.cbsnews.com/video/the-history-of-the-penny/ www.history.com/news/10-things-you-didnt-know-about-the-penny www.usmint.gov/coins/coin-medal-programs/circulating-coins/penny www.usmint.gov/learn/kids/library/circulating-coins/penny flinnsci.com ©2020 Flinn Scientific, Inc. -

Louise Penny's February Newsletter

04/01/2016 Louise Penny Newsletter To view this email with images click here Louise Penny's February Newsletter Shoot a few scenes out of focus. I want to win the foreign film award. Billy Wilder Extreme weather The Beautiful Mystery What a very odd month January has been! (Of course, being a proud US / Canada / UK Canadian, I'm referring to the weather.) A January thaw saw us practically in shirtsleeves, then down to minus 30 that saw us broadening our vocabulary. I know we here in Quebec were not alone, there was extreme weather in many places. But for me personally, January has been a nice mix of staying at home by the fire, and doing a bit of traveling, promoting the Gamache books. BURY YOUR DEAD French book launch Was in Quebec City midmonth for the launch of ENTERREZ VOS MORTS (French language version of BURY YOUR DEAD where it became an immediate bestseller!). Plans are underway with one of the preeminent walking tour companies in the city to create a Gamache tour of the glorious city, visiting many of the sites and bistros the Chief Inspector goes to as he investigates, and heals. Click if you wish to order Including, of course, the magnificent Literary and Historical Society Barnes & Noble.com in the Morrin Centre. It won't be available until early summer, but I'll Amazon.com let you know as soon as there's more to say. Amazon.ca Amazon.co.uk Gamache in 25 languages ABA American Then home for a week and the fun news that we've sold the Booksellers Association translation rights to a publisher in Brazil. -

Effects of Wildfire on Drinking Water Utilities and Effective Practices for Wildfire Risk Reduction and Mitigation

Report on the Effects of Wildfire on Drinking Water Utilities and Effective Practices for Wildfire Risk Reduction and Mitigation Report on the Effects of Wildfire on Drinking Water Utilities and Effective Practices for Wildfire Risk Reduction and Mitigation August 2013 Prepared by: Chi Ho Sham, Mary Ellen Tuccillo, and Jaime Rooke The Cadmus Group, Inc. 100 5th Ave., Suite 100 Waltham, MA 02451 Jointly Sponsored by: Water Research Foundation 6666 West Quincy Avenue, Denver, CO 80235-3098 and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Washington, D.C. Published by: [Insert WaterRF logo] DISCLAIMER This study was jointly funded by the Water Research Foundation (Foundation) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). The Foundation and USEPA assume no responsibility for the content of the research study reported in this publication or for the opinions or statements of fact expressed in the report. The mention of trade names for commercial products does not represent or imply the approval or endorsement of either the Foundation or USEPA. This report is presented solely for informational purposes Copyright © 2013 by Water Research Foundation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication may be copied, reproduced or otherwise utilized without permission. ISBN [inserted by the Foundation] Printed in the U.S.A. CONTENTS DISCLAIMER.............................................................................................................................. iv CONTENTS.................................................................................................................................. -

The Opper Penny

the opper enny The opper Penny (A Scholarly On‐Line Journal for Copper Mountain College) Throughout existence, objects often portray meaning. For example, the historical importance of copper is evident by its use in legends, art, medicine, trade, and technology. Its metallic brilliance is enshrined in the word “liberty” that beams forth from America’s copper penny. Like the Statue of Liberty, plated with copper, its green coloring offering evidence of natural weathering, the copper penny endures. This journal is intended as a beacon of liberty, a celebration of expression, and the renewal of meaning. ‐‐‐‐ Aimee` Percy (2010) 2 | Page The Copper Penny The opper Penny, an online journal of Copper Mountain College, accepts scholarly papers, essays, and articles. All submissions remain the sole property of the author. Student work must be submitted by the faculty member in whose class the work was written. The names of the author and sponsoring faculty member will accompany the accepted submission in the journal. Work not completed in CMC classes, or for whom the faculty of record is not available, may be submitted directly to Professors Cathy Itnyre or Mike Danza for review by two or more faculty. Both the author and sponsoring faculty must attest to the quality, format, and high academic standards of the submitted work. Send submissions to: The opper Penny Copper Mountain College 6162 Rotary Way Joshua Tree, CA 92252 Please complete the following: Date of Submission: _____________________ Full Name of Student Author:_____________________________________________________________ -

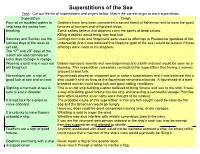

Superstitions of the Sea Task: Cut out the List of Superstitions and Origins Below

Superstitions of the Sea Task: Cut out the list of superstitions and origins below. Match the correct origin to each superstition. Superstition Origin Pour oil on troubled waters to Dolphins have long been considered a sacred friend of fishermen and to have the good help keep the waves from fortunes of humans and will protect ships. breaking Some sailors believe that dolphins carry the spirits of dead sailors. Killing a dolphin would bring very bad luck. Saturday and Sunday are the Cuttings form hair and fingernails were used as offerings to Prosperina (goddess of the luckiest days of the week to underworld) And it was believed that Neptune (god of the sea) would be jealous if these set sail. offerings were made in his kingdom. The 17th and 29th days of the month are also considered lucky days to begin a voyage. Wearing a gold ring in your ear Babies represent new life and new beginnings and a birth onboard would be seen as a will bring luck blessing. This superstition completely contradicts the superstition that having a woman onboard is bad luck. Horseshoes are a sign of Figureheads played an important part in sailor’s superstitions and it was believed that a good luck at sea and on land ship couldn’t sink as long as the figurehead remained attached. A figurehead of a bare breasted woman could bring luck and good dialing conditions. Sighting a mermaid at sea is This is an old ship building custom believed to bring fortune and luck to the ship. It was sure to end in disaster a way of building good fortune into the ship and ensuring a successful voyage.