The Edinburgh 1970 British Commonwealth Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

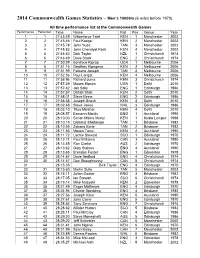

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men's

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men’s 10000m (6 miles before 1970) All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 27:45.39 Wilberforce Talel KEN 1 Manchester 2002 2 2 27:45.46 Paul Kosgei KEN 2 Manchester 2002 3 3 27:45.78 John Yuda TAN 3 Manchester 2002 4 4 27:45.83 John Cheruiyot Korir KEN 4 Manchester 2002 5 5 27:46.40 Dick Taylor NZL 1 Christchurch 1974 6 6 27:48.49 Dave Black ENG 2 Christchurch 1974 7 7 27:50.99 Boniface Kiprop UGA 1 Melbourne 2006 8 8 27:51.16 Geoffrey Kipngeno KEN 2 Melbourne 2006 9 9 27:51.99 Fabiano Joseph TAN 3 Melbourne 2006 10 10 27:52.36 Paul Langat KEN 4 Melbourne 2006 11 11 27:56.96 Richard Juma KEN 3 Christchurch 1974 12 12 27:57.39 Moses Kipsiro UGA 1 Delhi 2010 13 13 27:57.42 Jon Solly ENG 1 Edinburgh 1986 14 14 27:57.57 Daniel Salel KEN 2 Delhi 2010 15 15 27:58.01 Steve Binns ENG 2 Edinburgh 1986 16 16 27:58.58 Joseph Birech KEN 3 Delhi 2010 17 17 28:02.48 Steve Jones WAL 3 Edinburgh 1986 18 18 28:03.10 Titus Mbishei KEN 4 Delhi 2010 19 19 28:08.57 Eamonn Martin ENG 1 Auckland 1990 20 20 28:10.00 Simon Maina Munyi KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 21 21 28:10.15 Gidamis Shahanga TAN 1 Brisbane 1982 22 22 28:10.55 Zakaria Barie TAN 2 Brisbane 1982 23 23 28:11.56 Moses Tanui KEN 2 Auckland 1990 24 24 28:11.72 Lachie Stewart SCO 1 Edinburgh 1970 25 25 28:12.71 Paul Williams CAN 3 Auckland 1990 25 26 28:13.45 Ron Clarke AUS 2 Edinburgh 1970 27 27 28:13.62 Gary Staines ENG 4 Auckland 1990 28 28 28:13.65 Brendan Foster ENG 1 Edmonton 1978 29 29 28:14.67 -

Draft Inverleith Conservation Area Character Appraisal

INVERLEITH CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL Contents 1. Summary information 2 2. Conservation area character appraisals 3 3. Historical origins and development 4 4. Special characteristics 4.1 Structure 7 4.2 Key elements 10 5. Management 5.1 Legislation, policies and guidance 15 5.2 Pressures and sensitivities 20 5.3 Opportunities for development 21 5.4 Opportunities for planning action 22 5.5 Opportunities for enhancement 22 6. Sources 24 1 1. Summary information Location and boundaries The Inverleith Conservation Area is located to the north of the New Town Conservation Area, 1.5 kilometres north of the city centre and covers an area of 232 hectares. The conservation area is bounded by Ferry Road to the north, the western boundary of Fettes College, the eastern boundary of Warriston Cemetery and Comely Bank/Water of Leith/Glenogle Road to the south. The boundary includes Fettes College, Inverleith Park, the Royal Botanic Garden, Warriston Cemetery and Tanfield. The area falls within Inverleith, Forth and Leith Walk wards and is covered by the Stockbridge/Inverleith, Trinity and New Town/Broughton Community Councils. The population of Inverleith Conservation Area in 2011 was 4887. Dates of designation/amendments The conservation area was originally designated in October 1977. The boundary was amended in 1996 and again in 2006 to exclude areas which no longer contributed to the character of the conservation area. A conservation area character appraisal was published in 2006, and a management plan in 2010. The Stockbridge Colonies were removed from the Inverleith Conservation Area boundary in 2013 to form a separate conservation area. -

Hall of Fame

scottishathletics HALL OF FAME 2018 October A scottishathletics history publication Hall of Fame 1 Date: CONTENTS Introduction 2 Jim Alder, Rosemary Chrimes, Duncan Clark 3 Dale Greig, Wyndham Halswelle 4 Eric Liddell 5 Liz McColgan, Lee McConnell 6 Tom McKean, Angela Mudge 7 Yvonne Murray, Tom Nicolson 8 Geoff Parsons, Alan Paterson 9 Donald Ritchie, Margaret Ritchie 10 Ian Stewart, Lachie Stewart 11 Rosemary Stirling, Allan Wells 12 James Wilson, Duncan Wright 13 Cover photo – Allan Wells and Patricia Russell, the daughter of Eric Liddell, presented with their Hall of Fame awards as the first inductees into the scottishathletics Hall of Fame (photo credit: Gordon Gillespie). Hall of Fame 1 INTRODUCTION The scottishathletics Hall of Fame was launched at the Track and Field Championships in August 2005. Olympic gold medallists Allan Wells and Eric Liddell were the inaugural inductees to the scottishathletics Hall of Fame. Wells, the 1980 Olympic 100 metres gold medallist, was there in person to accept the award, as was Patricia Russell, the daughter of Liddell, whose triumph in the 400 metres at the 1924 Olympic Games was an inspiration behind the Oscar-winning film Chariots of Fire. The legendary duo were nominated by a specially-appointed panel consisting of Andy Vince, Joan Watt and Bill Walker of scottishathletics, Mark Hollinshead, Managing Director of Sunday Mail and an on-line poll conducted via the scottishathletics website. The on-line poll resulted in the following votes: 31% voting for Allan Wells, 24% for Eric Liddell and 19% for Liz McColgan. Liz was inducted into the Hall of Fame the following year, along with the Olympic gold medallist Wyndham Halswelle. -

Norcal Running Review

The Northern California Running Review, formerly the West Ramirez. Juan is a freshman at San Jose City College and lives Valley Newsletter. is published on a monthly basis by the West at 64.6 Jackson Ave., San Jose, 95116 (Apt. 9) - Ph. 258-9865. Valley Track Club of San Jose, California. It is a communica- At 19, Juan has best times of 1:59.7, 4:28.3, and 9:51.7. He tion medium for all Northern California track and field ath- ran 19:45 for four miles cross country this past season, and letes, including age group, high school, collegiate, AAU, women, was a key factor in SJCC's high ranking in Northern California, and senior runners. The Running Review is available at many road races and track meets throughout Northern California for Some address changes for club members: Rene Yco has moved 25% an issue, or for $3-50 per year (first class mail). All to 1674 Adrian May, San Jose, 95122 (same phone); Sean O'Rior- West Valley TC athletes receive their copies free if their dues dan is now attending Washington State Univ. and has a new ad- are paid up for the year. dress of Neill Hall, %428, WSU, Pullman, Wash., 99163; Tony Ca sillas was inducted into the armed forces in February and can This paper's success depends on you, the readers, so please be reached (for a while anyway) by writing Pvt. Anthony Casillas, send us any pertinent information on the NorCal running scene (551-64-9872), Co. A BN2 BDE-1, Ft. -

NUTS NOTES Vol

NUTS NOTES Vol. 18 No.3 June 1980 Editor: Tim Lynch-Staunton, Meadowbank, Eydens Avenue, Walton-on-Thamee, Surrey KT12 3 JP. This is the third issue of NUTS NOTES to go on sale to the general public* For the last twenty or so years it has been available to members of the NUTS on a quarterly basis, thanks mainly to the untiring efforts of Andrew Huxtable, who was editor for many years until last year. We hope this issue will be of interest to athletics fans, in particular those who like athletics' statistics, although it will not in future be entirely a statistical newsletter, and will encourage those who compile lists and other data for their own amusement to submit compilations for consideration for inclusion in future issues. T.L-S. BRITISH BEST PERFORMANCES OF ALL-TIME - 10 MILES (ROAD) One of the most frequently contested yet least documented distance events is the 10 miles. So far as I am aware, no one has previously attempted to produce an all- time list for road performances. There are, of course, certain inherent problems. It's an event which, like the marathon, is subject to considerable variation in the severity of courses; and it is sometimes difficult to establish for sure the accuracy of distance for races advertised as being at 10 miles. But there are several very good reasons for establishing a statistical record of the event. First, almost all top-class distance-runners contest it during their career. Second, it brings together trackmen, cross-country runners and marathoners. Third, it has also produced a significant number of performers who have not achieved major recognition in other events. -

Boards Were Presented on the 31..01.19 and Include Initial Concept Design for Consultation Purposes

Boards were presented on the 31..01.19 and include initial concept design for consultation purposes. Boards were presented on the 31..01.19 and include initial concept design for consultation purposes. Welcome Introduction The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) is bringing forward the Edinburgh Biomes project in order to protect its unique and globally important plant collection. The project will address an urgent need to restore and replace RBGE's mission critical buildings to deliver world-leading facilities that will protect RBGE's work for the future, enabling Scotland to maintain its leading reputation in plant research and conservation. We have now held two public consultation events where information was presented relative to the following: • Nursery Application (Submitted, Dec 2018) • Gardens Major Application (Expected, Feb 2019) This our final consultation event as part of the planning application process and provides further developed proposals whilst responding to issues previously raised. New Refurbishment/Alteratio Glasshouse n of Listed Structures and Glass Houses There is ongoing consultation with City of Edinburgh Council, Historic Environment Scotland and other statutory consultees. New Buildings - Plant Health Suite, Sustainable We welcome your feedback – please fill in one of the comment Energy Centre and New Glasshouse forms provided. Refurbishment/alteration of Listed Glasshouses Selected demolition works and construction of new and Structures research Glasshouses, Education and Support Facilities Boards were presented on the 31..01.19 and include initial concept design for consultation purposes. Edinburgh Biomes – Vision RBGE Mission The mission of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) is to ‘Explore, Conserve and Explain the World of Plants for a Better Future’. -

HOLY ISLAND, ALNWICK & the KINGDOM of NORTHUMBRIA Please Note That This Tour Includes a Crossing Over to Holy Island Via A

HOLY ISLAND, ALNWICK & THE KINGDOM OF NORTHUMBRIA Please note that this tour includes a crossing over to Holy Island via a causeway. Sometimes this route will be taken in reverse, depending on tidal timings. After leaving the city we travel through a county called East Lothian, full of rich farmland with a range of hills away to the right, the Lammermuirs. We pass by the town of Musselburgh, home of the world’s oldest golf course – it dates back to 1672 and has been the venue for the Open Championship six times. At Prestonpans a battle took place in 1745 between a government army and one led by a famous figure in Scottish history, Bonnie Prince Charlie. This was the fifth and last Jacobite Uprising which were attempts to regain the throne for the deposed House of Stewart. All the uprisings ultimately failed but this battle was won by the Jacobites. At this point you will see the Firth of Forth over to the left. This is an inlet of the North Sea that separates Britain from mainland Europe. Soon we drive inland and pass Haddington on our right, the county town for East Lothian and a pleasant market town. Soon we pass Dunbar away to our left. It has a ruined castle overlooking the harbour. There were two battles fought close to Dunbar in 1296 & 1650, both defeats for the Scots. A man called John Muir was born in Dunbar in 1838 - he emigrated to the USA aged 11 with his family and was to become a world-famous naturalist, environmentalist, explorer & geologist – he is known as the ‘Father of World Conservation’. -

1974 Age Records

TRACK AGE RECORDS NEWS 1974 TRACK & FIELD NEWS, the popular bible of the sport for 21 years, brings you news and features 18 times a year, including twice a month during the February-July peak season. m THE EXCITING NEWS of the track scene comes to you as it happens, with in-depth coverage by the world's most knowledgeable staff of track reporters and correspondents. A WEALTH OF HUMAN INTEREST FEATURES involving your favor ite track figures will be found in each issue. This gives you a close look at those who are making the news: how they do it and why, their reactions, comments, and feelings. DOZENS OF ACTION PHOTOS are contained in each copy, recap turing the thrills of competition and taking you closer still to the happenings on the track. STATISTICAL STUDIES, U.S. AND WORLD LISTS AND RANKINGS, articles on technique and training, quotable quotes, special col umns, and much more lively reading complement the news and the personality and opinion pieces to give the fan more informa tion and material of interest than he'll find anywhere else. THE COMPREHENSIVE COVERAGE of men's track extends from the Compiled by: preps to the Olympics, indoor and outdoor events, cross country, U.S. and foreign, and other special areas. You'll get all the major news of your favorite sport. Jack Shepard SUBSCRIPTION: $9.00 per year, USA; $10.00 foreign. We also offer track books, films, tours, jewelry, and other merchandise & equipment. Write for our Wally Donovan free T&F Market Place catalog. TRACK & FIELD NEWS * Box 296 * Los Altos, Calif. -

Read Excerpt

SOPHIE CAMERON Roaring Brook Press New York 121-78529_ch01_5P.indd 3 04/23/19 11:54 AM Copyright © 2019 by Sophie Cameron Published by Roaring Brook Press Roaring Brook Press is a division of Holtzbrinck Publishing Holdings Limited Partnership 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010 fiercereads . com All rights reserved Library of Congress Control Number: 2018955879 ISBN: 978- 1- 250- 14993- 0 (hardcover) ISBN: 978- 1- 250- 14992- 3 (ebook) Our books may be purchased in bulk for promotional, educational, or business use. Please contact your local bookseller or the Macmillan Corporate and Premium Sales Department at (800) 221- 7945 ext. 5442 or by email at MacmillanSpecialMarkets@macmillan . com. Originally published in the United Kingdom by Pan Macmillan First American edition, 2019 Printed in the United States of America 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 121-78529_ch01_5P.indd 4 04/23/19 11:54 AM AUTUMN 121-78529_ch01_5P.indd 1 04/23/19 11:54 AM One This never would have happened if I hadn’t named the bloody cat Tinker Bell. He stares at me over Leanne Watson’s shoulder as she sprints up Leith Walk, his face squashed against her neck. Fake finger- nails dig into his ginger fur; one gold hoop earring falls over his head like a lopsided halo. Leanne glances back, almost tripping over a buggy sliding out of the co- op, and grins. “Come on, Fairy! Come save Tinker Bell!” Tink wriggles and yowls, the way he always does when any- one but me tries to pick him up, but Leanne’s grip is like a vise. -

Annual Report 2014/2015

british swimming annual report/ accounts 2015 2 BRITISH SWIMMING ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Cover photo: Adam Peaty with his gold medals from the 2015 world champion- ships. This page: James Guy displays his medals from the world championships 04 Chairman’s Report Maurice Watkins 05 Chief Executive’s Report David Sparkes 06 FINA WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS 2015 16 IPC swimming WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS 2015 24 EUROPEAN GAMES 2015 32 INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS 34 EXCELLENCE 46 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 47 Financial Statements 52 Acknowledgements 4 BRITISH SWIMMING ANNUAL REPORT 2015 5 Tully Kearney British Swimming Annual Report Company Information For the year ended 31 March 2015 CHAIRMAN Edward Maurice Watkins CBE DIRECTORS Maureen Campbell Guy Savaric Scott Davis (resigned 31 December 2014) Graham Ian Edmunds William Raymond Gordon Samuel Greetham (resigned 31 December 2014) John Craig Hunter Robert Michael Kenneth John James Alexandra Joanne Kelham (appointed 18 October 2014) Peter Jeremy Littlewood (appointed 1 January 2015) Michael John Power OBE Simon Rothwell David Sparkes OBE Adele Stach-Kevitz COMPANY SECRETARY Ashley Cox COMPANY REGISTRATION NUMBER 4092510 REGISTERED OFFICE British Swimming Pavilion 3 SportPark 3 Oakwood Drive Loughborough LE11 3QF BANKERS Lloyds Bank Kleinwort Benson Coutts & Co. 37/38 High Street 14 St. George Street 440 Strand Loughborough London London Leicestershire W1S 1FE WC2R 0QS LE11 2QG AUDITOR Haysmacintyre 26 Red Lion Square London WC1R 6 BRITISH SWIMMING ANNUAL REPORT 2015 7 ^ maurice watkins CBE ^ david sparkes OBE chief chairman’s executive’s report// report// t the time of writing this, my third synchro and masters at the London Aquatics year of further change for British improvements last year and we remain report as Chairman of British Centre. -

CGS Quad Report 2019 DEFIN.Indd

COMMONWEALTH GAMES SCOTLAND Quadrennial Report 2015–2019 Thank you for your support PARTNERS SUPPORTERS PROUD TO SERVE SCOTLAND SUPPLIERS ParkTHE Practice ASSOCIATED CHARITIES A WORLD CLASS SPORTING SYSTEM FOR EVERYONE Our mission is to build a world class sporting system for everyone in Scotland. By world class we mean being ambitious and aspiring to be the best we can be at all levels in sport. We see a Scotland where sport is a way of life, at the heart of society, making a positive impact on people and communities. Athlete of the Games Duncan Scott, Swimming GOLD Men’s 100m Freestyle SILVER Men’s 200m Individual Medley BRONZE Men’s 200m Freestyle Men’s 200m Butterfly Men’s 4x100m Freestyle Relay Men’s 4x200m Freestyle Relay Winner: Emirates Lonsdale Trophy – Scottish Sportsperson of the Year 2018 CONTENTS Chair’s Report 2015 – 2019 .............................................................................................. 5 Chief Executive’s Report 2015 – 2019 .............................................................................. 7 Finance Report 2015 – 2019 .......................................................................................... 15 2018 Commonwealth Games ....................................................................................... 19 Gold Coast 2018 Medal Table ........................................................................................ 20 2018 Team Scotland Medallists ...................................................................................... 21 2018 Team Scotland Representatives -

Colinton Primary School Handbook 2020-2021

Colinton Primary School Handbook 2020 - 2021 1 A Foreword from the Executive Director of Communities and Families Session 2020 - 2021 Dear Parents/Carers, This brochure contains a range of information about your child’s school which will be of interest to you and your child. It offers an insight into the life and ethos of the school and also offers advice and assistance which you may find helpful in supporting and getting involved in your child’s education. We are committed to working closely with parents as equal partners in your child's education, in the life of your child's school and in city-wide developments in education. Parental involvement in the decision-making process and in performance monitoring are an integral part of school life. We look forward to developing that partnership with your support. Throughout this handbook the term ‘parent’ has the meaning attributed in the Standards in Scotland's Schools Act 2000 and the Scottish Schools (Parental Involvement) Act 2006. This includes grandparents, carer or anyone else who has parental responsibility for the child. I am pleased to introduce this brochure for session 2020 - 2021 and hope that it will provide you with the information you need concerning your child’s school. If you have any queries regarding the contents of the brochure please contact the Head Teacher of your child’s school in the first instance who will be happy to offer any clarification you may need. Alistair Gaw Executive Director of Communities and Families Children and Families Vision Our vision is for all children and young people in Edinburgh to enjoy their childhood and fulfil their potential.