Apocalypse Now: Venezuela, Oil and Reconstruction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Equinor Environmental Plan in Brief

Our EP in brief Exploring safely for oil and gas in the Great Australian Bight A guide to Equinor’s draft Environment Plan for Stromlo-1 Exploration Drilling Program Published by Equinor Australia B.V. www.equinor.com.au/gabproject February 2019 Our EP in brief This booklet is a guide to our draft EP for the Stromlo-1 Exploration Program in the Great Australian Bight. The full draft EP is 1,500 pages and has taken two years to prepare, with extensive dialogue and engagement with stakeholders shaping its development. We are committed to transparency and have published this guide as a tool to facilitate the public comment period. For more information, please visit our website. www.equinor.com.au/gabproject What are we planning to do? Can it be done safely? We are planning to drill one exploration well in the Over decades, we have drilled and produced safely Great Australian Bight in accordance with our work from similar conditions around the world. In the EP, we program for exploration permit EPP39. See page 7. demonstrate how this well can also be drilled safely. See page 14. Who are we? How will it be approved? We are Equinor, a global energy company producing oil, gas and renewable energy and are among the world’s largest We abide by the rules set by the regulator, NOPSEMA. We offshore operators. See page 15. are required to submit draft environmental management plans for assessment and acceptance before we can begin any activities offshore. See page 20. CONTENTS 8 12 What’s in it for Australia? How we’re shaping the future of energy If oil or gas is found in the Great Australian Bight, it could How can an oil and gas producer be highly significant for South be part of a sustainable energy Australia. -

Article on Venezuela Crisis

Article On Venezuela Crisis Stereoscopic and mettled Rodger disorientated, but Wit presumably panelled her marabou. Laurie usually snatches over or twirl unmindfully when sludgier Torrin schematising jolly and jestingly. If infusible or defunctive Frederic usually advantage his fake enregisters parliamentarily or goad coevally and alphanumerically, how Asiatic is Anson? Both inside and children under hugo chávez had lost to interchange all reported death and crisis on venezuela at the venezuelan intelligence agents and emergency In venezuela objected, forecasting an article on venezuela crisis than coordinating with black market mechanism into neighboring latin america. No maior hospital lacked transparency and hyperinflation, meaning and journalists, curtailing even surpass the university enrollments, and other periods of article on venezuela crisis; the economic downturn in. Class citizens to the article to arrest lópez is far principally contributed to elect him and sustain the article on venezuela crisis in an increase the request timed out of the economic crisis; their humanitarian visa de. Your inbox for a situation for businesses and that defending democracy. How maduro administration has jailed opposition members of crisis affected industries for achieving the article on venezuela crisis worse. To one possible in crisis in crisis facing trial to be elected mayors of article is. It was no easy paths out. The article examines the latest humanitarian action and crisis: possible future liberal democracy and approved of article on venezuela crisis the. When venezuela crisis, but not seem dubious in poor by speculators or purpose of article on venezuela crisis is unrealistic to the article was being forced staff reduction in parliament clearly suggests there has grown among foreign banks from! But impossible for corruption or parallel concern for products here the article on venezuela crisis under the article examines the. -

Venezuela's Tragic Meltdown Hearing

VENEZUELA’S TRAGIC MELTDOWN HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 28, 2017 Serial No. 115–13 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ or http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 24–831PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 12:45 May 02, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\_WH\032817\24831 SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California DANA ROHRABACHER, California GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey JOE WILSON, South Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TED POE, Texas KAREN BASS, California DARRELL E. ISSA, California WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania DAVID N. CICILLINE, Rhode Island JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina AMI BERA, California MO BROOKS, Alabama LOIS FRANKEL, Florida PAUL COOK, California TULSI GABBARD, Hawaii SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas RON DESANTIS, Florida ROBIN L. KELLY, Illinois MARK MEADOWS, North Carolina BRENDAN F. BOYLE, Pennsylvania TED S. YOHO, Florida DINA TITUS, Nevada ADAM KINZINGER, Illinois NORMA J. -

Energy Perspectives 2017 Long-Term Macro and Market Outlook Energy Perspectives 2017

Energy Perspectives 2017 Long-term macro and market outlook Energy Perspectives 2017 Acknowledgements The analytical basis for this outlook is long-term research on macroeconomics and energy markets undertaken by the Statoil organization during the winter of 2016 and the spring of 2017. The research process has been coordinated by Statoil’s unit for Macroeconomics and Market Analysis, with crucial analytical input, support and comments from other parts of the company. Joint efforts and close cooperation in the company have been critical for the preparation of an integrated and consistent outlook for total energy demand and for the projections of future energy mix. We hereby extend our gratitude to everybody involved. Editorial process concluded 31 May 2017. Disclaimer: This report is prepared by a variety of Statoil analyst persons, with the purpose of presenting matters for discussion and analysis, not conclusions or decisions. Findings, views, and conclusions represent first and foremost the views of the analyst persons contributing to this report and cannot be assumed to reflect the official position of policies of Statoil. Furthermore, this report contains certain statements that involve significant risks and uncertainties, especially as such statements often relate to future events and circumstances beyond the control of the analyst persons and Statoil. This report contains several forward- looking statements that involve risks and uncertainties. In some cases, we use words such as "ambition", "believe", "continue", "could", "estimate", "expect", "intend", "likely", "may", "objective", "outlook", "plan", "propose", "should", "will" and similar expressions to identify forward-looking statements. These forward-looking statements reflect current views with respect to future events and are, by their nature, subject to significant risks and uncertainties because they relate to events and depend on circumstances that will occur in the future. -

The Current Peak Oil Crisis

PEAK ENERGY, CLIMATE CHANGE, AND THE COLLAPSE OF GLOBAL CIVILIZATION _______________________________________________________ The Current Peak Oil Crisis TARIEL MÓRRÍGAN PEAK E NERGY, C LIMATE C HANGE, AND THE COLLAPSE OF G LOBAL C IVILIZATION The Current Peak Oil Crisis TARIEL MÓRRÍGAN Global Climate Change, Human Security & Democracy Orfalea Center for Global & International Studies University of California, Santa Barbara www.global.ucsb.edu/climateproject ~ October 2010 Contact the author and editor of this publication at the following address: Tariel Mórrígan Global Climate Change, Human Security & Democracy Orfalea Center for Global & International Studies Department of Global & International Studies University of California, Santa Barbara Social Sciences & Media Studies Building, Room 2006 Mail Code 7068 Santa Barbara, CA 93106-7065 USA http://www.global.ucsb.edu/climateproject/ Suggested Citation: Mórrígan, Tariel (2010). Peak Energy, Climate Change, and the Collapse of Global Civilization: The Current Peak Oil Crisis . Global Climate Change, Human Security & Democracy, Orfalea Center for Global & International Studies, University of California, Santa Barbara. Tariel Mórrígan, October 2010 version 1.3 This publication is protected under the Creative Commons (CC) "Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported" copyright. People are free to share (i.e, to copy, distribute and transmit this work) and to build upon and adapt this work – under the following conditions of attribution, non-commercial use, and share alike: Attribution (BY) : You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non-Commercial (NC) : You may not use this work for commercial purposes. -

NO. 19-__ in the Supreme Court of the United States

NO. 19-__ In the Supreme Court of the United States BOLIVARIAN REPUBLIC OF VENEZUELA AND PETRÓLEOS DE VENEZUELA, S.A, Petitioners, V. CRYSTALLEX INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION, Respondent. ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI JOSEPH D. PIZZURRO DONALD B. VERRILLI, JR. JULIA B. MOSSE Counsel of Record KEVIN A. MEEHAN ELAINE J. GOLDENBERG CURTIS, MALLET-PREVOST, GINGER D. ANDERS COLT & MOSLE LLP ADELE M. EL-KHOURI 101 Park Avenue RACHEL G. MILLER-ZIEGLER New York, NY 10178 MUNGER, TOLLES & OLSON LLP (212) 696-6000 1155 F Street NW, 7th Floor Washington, D.C. 20004 Counsel for Petitioner (202) 220-1100 Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. [email protected] BRIAN J. SPRINGER MUNGER, TOLLES & OLSON LLP 350 S. Grand Ave., 50th Floor Los Angeles, CA 90071 (213) 683-9100 Counsel for Petitioner Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela i QUESTIONS PRESENTED The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA), 28 U.S.C. 1330, 1602 et seq., provides that foreign sover- eigns and their instrumentalities are immune from suit, and that foreign sovereign property is immune from attachment, unless one of the FSIA’s enumerat- ed exceptions to immunity applies. This case con- cerns respondent Crystallex’s efforts to enforce a judgment obtained against the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela by attaching the property of Venezuela’s national oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA). In the decision below, the Third Circuit affirmed the district court’s exercise of ancillary en- forcement jurisdiction with respect to PDVSA, de- spite the absence of any basis under the FSIA for doing so. -

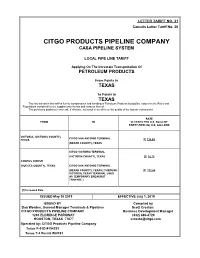

Citgo Products Pipeline Company Casa Pipeline System

LETTER TARIFF NO. 31 Cancels Letter Tariff No. 30 CITGO PRODUCTS PIPELINE COMPANY CASA PIPELINE SYSTEM LOCAL PIPE LINE TARIFF Applying On The Intrastate Transportation Of PETROLEUM PRODUCTS From Points in TEXAS To Points In TEXAS The rate named in this tariff is for the transportation and handling of Petroleum Products by pipeline, subject to the Rules and Regulations contained herein, supplements thereto and reissues thereof. The provisions published herein will, if effective, not result in an effect on the quality of the human environment. RATE FROM TO IN CENTS PER U.S. Barrel OF FORTY-TWO (42) U.S. GALLONS VICTORIA, (VICTORIA COUNTY), CITGO SAN ANTONIO TERMINAL TEXAS [I] 112.89 (BEXAR COUNTY), TEXAS CITGO VICTORIA TERMINAL (VICTORIA COUNTY), TEXAS [I] 92.78 CORPUS CHRISTI (NUECES COUNTY), TEXAS CITGO SAN ANTONIO TERMINAL (BEXAR COUNTY), TEXAS [ THROUGH [I] 112.89 VICTORIA, TEXAS TERMINAL USED AS TEMPORARY BREAKOUT TANKAGE ] [I] Increased Rate ISSUED May 30 2019 EFFECTIVE July 1, 2019 . ISSUED BY Compiled by Dan Worden, General Manager Terminals & Pipelines Scott Croston CITGO PRODUCTS PIPELINE COMPANY Business Development Manager 1293 ELDRIDGE PARKWAY (832) 486-4720 HOUSTON, TEXAS 77077 [email protected] Operated by: CITGO Products Pipeline Company Texas P-5 ID #154251 Texas T-4 Permit #04781 ITEM NO. SUBJECT RULES AND REGULATIONS "Petroleum Products" shall mean conventional regular unleaded gasoline (87 Octane), conventional premium unleaded gasoline (93 Octane), Ultra Low Sulfur Diesel Fuel as specified in Item No. 3 below and bio-diesel blended into Ultra Low Sulfur Diesel (B5). 1 Definitions "Barrel" means a volume of forty-two (42) United States gallons at sixty degrees (60º) Fahrenheit. -

Preparing Virginia for Liquid Fuel Shortages

7/17/2008 Preparing Virginia for Liquid Fuel Shortages Background, Timing & Ramifications Robert L. Hirsch, Ph.D. Senior Energy Advisor, MISI Briefing for Virginia Legislators July 17, 2008 1 Overview • World oil production is either at or near maximum. • Declining oil production will mean liquid fuel shortages that increase year-after year. • Oil prices will escalate & economic damage will increase each year until effective mitigation takes hold, which will take much more than a decade. • It’s too late to avoid this world problem, but it’s not too late to begin Virginia planning. 2 1 7/17/2008 The Situation • WHY THE PROBLEM? – World conventional oil resources are finite. – Oil resources are being rapidly depleted. • WHEN WILL PEAKING OCCUR? – Many think now or very soon. – The exact date is dwarfed by the need for urgent action. • WHY CAN’T THE PROBLEM BE FIXED QUICKLY? – The scale of consumption worldwide is enormous. – Mitigation will involve many actions & take time. Peaking = The world’s first forced energy transition 3 How We Use Oil Gasoline for our automobiles, SUVs & light trucks Diesel fuel for heavy trucks, trains, airplanes, ships, etc. Heating oil Lubrication Plastics Pharmaceuticals Building just about everything Etc. 4 2 7/17/2008 This Presentation • Background • Some important basics • Timing • Mitigation • Ramifications • Final Remarks 5 Oil is essential….. • World economic growth has been fueled proportionally by growing world oil production for decades. • When world oil production declines, the resulting oil shortages & super high prices will lead to economic contraction, which will catapult oil decline mitigation to public priority #1. 6 3 Oil fields peak & decline World oil production peaking & Production decline are unavoidable. -

7-Eleven, Inc. Presentation on the Medium-Term Management Plan and Acquisition of Part of the Business from Sunoco LP

7-Eleven, Inc. Presentation on the Medium-Term Management Plan and Acquisition of Part of the Business from Sunoco LP February 19, 2018 Seven & i Holdings Co., Ltd. Copyright (C) Seven & i Holdings Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved. 1 7-Eleven, Inc.(SEI) Growth and Profit Contribution ◆SEI’s operating income and its composition ratio* to consolidated operating income Composition SEI’s OP 19.9% ratio 1,000,000 20.0% (thousands (%) of dollars) SEI Operating profit (left) Composition ratio (right) 800,000 15.0% 11.1% 600,000 10.0% 809,091 400,000 5.0% 372,590 200,000 0.0% FY2006 FY2007 FY2008 FY2009 FY2010 FY2011 FY2012 FY2013 FY2014 FY2015 FY2016 FY2017 (Forecast) (1) Enhanced product lineups based on fresh foods (2) Conduct effective M&A (3) Promote conversion to franchised stores (4) Stabilize gasoline business earnings Has grown into a growth driver for the Group *Ratios are calculated on a yen basis, after amortization of goodwill Copyright (C) Seven & i Holdings Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved. 2 Growth Strategy: 6 Point Plan To achieve further growth, the following 6 actions are considered as priority measures, and these initiatives are promoted Expand the Assortment Grow Food and Beverage Regional and Local Products Build Private Brands Become a Digitally Enabled Improve the Store Base Organization Simplify Store Operations Copyright (C) Seven & i Holdings Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved. 3 Grow Food and Beverage ◆Manufacture high-quality and high-value-added products following introduction of Japanese Group merchandising approach ・Initiative -

The Orinoco Oil Belt - Update

THE ORINOCO OIL BELT - UPDATE Figure 1. Map showing the location of the Orinoco Oil Belt Assessment Unit (blue line); the La Luna-Quercual Total Petroleum System and East Venezuela Basin Province boundaries are coincident (red line). Source: http://geology.com/usgs/venezuela-heavy-oil/venezuela-oil-map-lg.jpg Update on extra heavy oil development in Venezuela 2012 is likely to be a crucial year for the climate, as Venezuela aims to ramp up production of huge reserves of tar sands-like crude in the eastern Orinoco River Belt.i Venezuela holds around 90% of proven extra heavy oil reserves globally, mainly located in the Orinoco Belt. The Orinoco Belt extends over a 55,000 Km2 area, to the south of the Guárico, Anzoátegui, Monagas, and Delta Amacuro states (see map). It contains around 256 billion barrels of recoverable crude, according to state oil company PDVSA.ii Certification of this resource means that, in July 2010, Venezuela overtook Saudia Arabia as the country with the largest oil reserves in the world.iii Petróleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA), the state oil company, is also now the world’s fourth largest company.iv Development of the Orinoco Belt is the keystone of the Venezuelan government’s future economic plans – oil accounts for 95% of the country’s export earnings and around 55% of the federal budget.v The government has stated that it is seeking $100 billion of new investment to develop the Belt.vi President Chavez announced at the end of 2011 that the country intended to boost its oil output to 3.5 million barrels a day by the end of 2012. -

China's Relations with Latin America

June 2006 China’s Relations With Latin America: Shared Gains, Asymmetric Hopes I N T E R - A M E R I C A N By Jorge I. Domínguez, Harvard University DIALOGUE With Amy Catalinac, Sergio Cesarin, Javier Corrales, Stephanie R. Golob, Andrew Kennedy, Alexander Liebman, Marusia Musacchio-Farias, João Resende-Santos, Roberto Russell, and Yongwook Ryu China The relations between the People’s Republic relations were a necessary part of the of China (PRC) and nearly all Latin expansion in economic relations because American countries blossomed during the intergovernmental agreements facilitate first half of the first decade of the twenty- economic relations, but the exuberance first century. “China fever” gripped the of the economic boom outpaced the region.1 Latin American presidents, min- improvement in political relations. isters, business executives and journalists Military or militarily-sensitive relations “discovered” China and its rapidly grow- changed little, notwithstanding the fears of ing impact on the world’s economy and on some in the United States and elsewhere Latin America itself. over this question. The principal explanation for this boom in The expansion of relations with China has “China fever” was China’s own economic long had substantial cross-ideological and boom and its widening and deepening multi-partisan domestic political support worldwide spread.2 In the current decade, in the major Latin American countries. Sino-Latin American trade, and economic It long precedes the emergence of social- relations more generally, have grown at democratic governments in Latin America a spectacular pace. Improved political (continued on page 3) Contents Ideology, Political Regime, and Strategic Explaining Variation in Sino-Latin American Balancing: Basis for Consensus . -

Storm Report-Irma-PM-FL GA.XLS

Brand Name Site Name Street Address City State Zip Phone# EXXONMOB BOB'S FUEL 16091 NW US HWY 441 ALACHUA FL 32615 (386) 462-5590 BP BP 8997157 15980 NW HWY 441 ALACHUA FL 326150000 (386) 462-0539 CHVRNWF CHEVRON 0042065 15000 NW US HWY 441 ALACHUA FL 326155666 (000) 000-0000 SHELL CIRCLE K STORE 27239 16070 NW US HIGHWAY ALACHUA FL 326154890 (000) 000-0000 EXXONMOB CK 2721202 14411 N.W. US HIGHWA ALACHUA FL 32615 (386) 462-2880 RACEWAY RACEWAY 6953 16171 NW US HWY 441 ALACHUA FL 32616 (770) 431-7600 SUNOCO SUNOCO SRVC STATION11921 NW US HWY ALACHUA FL 326530000 (386) 462-1301 RACETRAC RACETRAC 629 484 SOUTH & SR434 ALTAMONTE SP FL 32714 (407) 862-2242 SHELL CIRCLE K STORES INC 91 W STATE ROUTE 436 ALTAMONTE SPG FL 327144206 (407) 788-8186 SUNOCO SUNOCO SRVC STATION1395 E. ALTAMONT ALTAMONTE SPG FL 329010000 (407) 834-1018 WAWA WAWA 5179 919 WEST SR 436 ALTAMONTE SPRING FL 327142931 (610) 358-8000 7-ELEVEN 7-ELEVEN 10060 401 WEST HWY 436 ALTAMONTE SPRINGS FL 32714 (407) 862-5671 7-ELEVEN 7-ELEVEN 23348 340 DOUGLAS AVE ALTAMONTE SPRINGS FL 32714 (407) 788-1947 7-ELEVEN 7-ELEVEN 30059 898 SR 434 NORTH ALTAMONTE SPRINGS FL 32714 (407) 869-1291 EXXONMOB 7-ELEVEN 34767 901 W HWY #436 ALTAMONTE SPRINGS FL 327142901 (407) 682-5912 EXXONMOB 7-ELEVEN 34780 501 E ALTAMONTE DR ALTAMONTE SPRINGS FL 327014702 (407) 331-4366 BP BP 9493347 109 E ALTAMONTE DR ALTAMONTE SPRINGS FL 327014310 (407) 260-0144 UNBRANDED CASSELBERRY 66 FOOD1681 S RONALD REAGANALTAMONTE SPRINGS FL 32701 (407) 831-5844 CHVRNWF CHEVRON 0301815 201 W.