Estonia External Relations Briefing: a Possible Critical Juncture: a Continuation E-MAP Foundation MTÜ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Young Leaders (Eyl40) 21St Century Pioneers: Inter-Regional Cooperation for a New Generation

SEPTEMBER 2017 EUROPEAN YOUNG LEADERS (EYL40) 21ST CENTURY PIONEERS: INTER-REGIONAL COOPERATION FOR A NEW GENERATION TALLINN SEMINAR Report of the three-day seminar EUROPEAN young L EADERS The European Young Leaders (EYL40) programme led by Friends of Europe is a unique, inventive and multi-stakeholder programme that aims to promote a European identity by engaging the continent’s most promising talents in initiatives that will shape Europe’s future. The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsi ble for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. With the support of SEPTEMBER 2017 EUROPEAN YOUNG LEADERS (EYL40) 21ST CENTURY PIONEERS: INTER-REGIONAL COOPERATION FOR A NEW GENERATION TALLINN SEMINAR Report of the three-day seminar EUROPEAN young L EADERS EUROPEAN YOUNG LEADERS This report reflects the seminar rapporteur’s understanding of the views expressed by participants. These views are not necessarily those of the organisations that participants represent, nor of Friends of Europe, its board of trustees, members or partners. Reproduction in whole or in part is permitted, provided that full credit is given to Friends of Europe, and that any such reproduction, whether in whole or in part, is not sold unless incorporated in other works. Rapporteurs: Paul Ames Publisher: Geert Cami Director of Programmes & Operations: Nathalie Furrer Senior Events Manager: -

Eu Whoiswho Official Directory of the European Union

EUROPEAN UNION EU WHOISWHO OFFICIAL DIRECTORY OF THE EUROPEAN UNION EUROPEAN COUNCIL 14/09/2021 Managed by the Publications Office © European Union, 2021 FOP engine ver:20180220 - Content: Anninter export. Root entity 1, all languages. - X15splt1,v170601 - X15splt2,v161129 - Just set reference language to EN (version 20160818) - Removing redondancy and photo for xml for pdf(ver 20201206,execution:2021-09-14T18:03:57.732+02:00 ) - convert to any LV (version 20170103) - NAL countries.xml ver (if no ver it means problem): 20210616-0 - execution of xslt to fo code: 2021-09-14T18:04:06.239+02:00- linguistic version EN - NAL countries.xml ver (if no ver it means problem):20210616-0 rootentity=EURCOU Note to the reader: The personal data in this directory are provided by the institutions, bodies and agencies of EU. The data are presented following the established order where there is one, otherwise by alphabetical order, barring errors or omissions. It is strictly forbidden to use these data for direct marketing purposes. If you detect any errors, please report them to: [email protected] Managed by the Publications Office © European Union, 2021 Reproduction is authorised. For any use or reproduction of individual photos, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. LIST OF BUILDINGS (CODES) Code City Adress DAIL Brussels Crèche Conseil Avenue de la Brabançonne 100 / Brabançonnelaan 100 JL Brussels Justus Lipsius Rue de la Loi 175 / Wetstraat 175 L145 Brussels Lex Rue de la Loi 145 / Wetstraat 145 EUROPEAN COUNCIL – 14/09/2021 – 3 BRUSSELS 4 – 14/09/2021 – OFFICIAL DIRECTORY OF THE EUROPEAN UNION BRUSSELS EUROPEAN COUNCIL – 14/09/2021 – 5 LUXEMBOURG – Kirchberg Plateau 6 – 14/09/2021 – OFFICIAL DIRECTORY OF THE EUROPEAN UNION LUXEMBOURG – Gare and Cloche d’or STRASBOURG EUROPEAN COUNCIL – 14/09/2021 – 7 European Council President 9 Members 9 Cabinet of the President 10 8 – 14/09/2021 – OFFICIAL DIRECTORY OF THE EUROPEAN UNION European Council Rue de la Loi 175 / Wetstraat 175 1048 Bruxelles / Brussel BELGIUM Tel. -

Sovereignty 2.0

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2021 Sovereignty 2.0 Anupam Chander Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Haochen Sun University of Hong Kong Faculty of Law This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/2404 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3904949 This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Computer Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Sovereignty 2.0 Anupam Chander* and Haochen Sun** Digital sovereignty—the exercise of control over the internet—is the ambition of the world’s leaders, from Australia to Zimbabwe, a bulwark against both foreign state and foreign corporation. Governments have resoundingly answered first-generation internet law questions of who if anyone should regulate the internet—they all will. We now confront second generation questions—not whether, but how to regulate the internet. We argue that digital sovereignty is simultaneously a necessary incident of democratic governance and democracy’s dreaded antagonist. As international law scholar Louis Henkin taught us, sovereignty can insulate a government’s worst ills from foreign intrusion. Assertions of digital sovereignty, in particular, are often double-edged—useful both to protect citizens and to control them. Digital sovereignty can magnify the government’s powers by making legible behaviors that were previously invisible to the state. Thus, the same rule can be used to safeguard or repress--a feature that legislators across the Global North and South should anticipate by careful checks and balances. -

The New European Parliament: a Look Ahead

THE NEW EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT: A LOOK AHEAD JUNE 2019 THE NEW EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT: A LOOK AHEAD More than 200 million EU citizens cast their votes between 23 and 26 May 2019 to choose the next cohort of MEPs. The new European Parliament is characterised by increased fragmentation and therefore a greater role for smaller parties. This briefing provides an overview of the The pro-European wave evidenced by the election results, explains what to expect rise of ALDE&R and the Greens coincided in the years to come and considers how with a sharp and unprecedented increase the new alignment of political groups will in voter engagement. Since the late 1970s, affect the EU’s balance of power. The turnout for the European elections had briefing also includes national steadily gone down, reaching a historic perspectives from Bulgaria, France, low of 43% in 2014. At 51%, this year’s Germany and the UK. In addition, we look turnout might be a significant outlier – or it at some of the key incoming and could show that, in an age of Brexit, outgoing MEPs and present a timeline of nationalism and climate change, the EU upcoming institutional changes. may yet have something unique to offer. The election results What to expect from the The 2019 elections marked the beginning 2019-2024 European of a new era: for the first time in the Parliament Parliament’s 40-year history, the two major A more collaborative Parliament parties have lost their majority. The centre- With the two biggest groups – the EPP right European People’s Party (EPP), and S&D – having shed seats and lost though still the largest group, saw the their combined absolute majority, the greatest reduction in seats, with the duopoly of power has been broken with centre-left Socialists and Democrats (S&D) smaller groups hoping this will be to their losing a similar number of MEPs. -

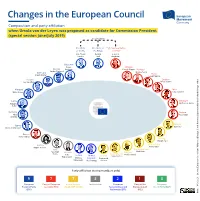

Changes in the European Council

Changes in the European Council Composition and party affiliation when Ursula von der Leyen was proposed as candidate for Commission President (special session June/July 2019) no voting rights President President of High Representative of the EC the EUCO of the EU Jean-Claude Donald Federica Juncker Tusk Mogherini Bulgarien Boyko Slovakia Croatia Borissow Peter Pellegrini Portugal Andrej Plenković António Costa Germany Malta Angela Merkel Joseph Muscat Ireland Sweden Leo Varadkar Stefan Löfven Hungary Spain Viktor Orbán Pedro Sánchez Latvia Denmark Krišjānis Mette Frederiksen Kariņš Romania Finland Sponsored by the Federal Foreign Office Klaus Antti Rinne | Johannis Estonia Cyprus Jüri Ratas Nicos Anastasiades Burak Korkmaz Greece Alexis Tsipras Design: Slovenia Marjan Šarec Austria Czech Republic Andrej Babiš Brigitte Bierlein Italy The Netherlands Giuseppe Lithuania Belgium Mark Rutte Conte Luxembourg Charles Michel Dalia Poland United France Grybauskaitė Xavier Bettel Mateusz Kingdom Emmanuel Morawiecki Theresa May Macron European Council and Wikipedia| Party affiliation (voting members only) | Source: | Source: 9 7 7 3 2 1 0 European Party of European Renew Europe - Independent European Party of the European People's Party Socialists (PES) (ALDE, EDP, LREM) Conservatives and European Left Green Party (EGP) 19/03/2021 (EPP) Reformists (ECR) (PEL) Date: Changes in the European Council Composition and party affiliation March 2021 no voting rights President President of High Representative of the EC the EUCO of the EU Ursula Charles Joseph von -

European Climate and Energy Experts

Journalism for the energy transition EXPERT EUROPEAN CLIMATE AND ENERGY EXPERTS Filters: Expert Type: Any, Topic: Elections & Politics, Location: Any Progressive, social-liberal, pro-European and green political party. Not represented in Parliament. Twitter: @progresivne_sk Location: Slovakia PRESS CONTACT Media office [email protected] Ľ Far-right neo-Nazi political party. Location: Slovakia PRESS CONTACT Office [email protected] ľ Conservative liberal political party. Twitter: @Veronika_Remis Location: Slovakia PRESS CONTACT Press office [email protected] Liberal and libertarian political party. Eurosceptic, advocates the liberalisation of drug laws and same-sex marriage. Rejects strict solutions to climate change. Member of the governing coalition. Twitter: @stranasas Location: Slovakia PRESS CONTACT Ondrej Šprlák, spokesperson [email protected] +421 910579204 Right-wing populist political party opposed to mass immigration. Second largest party in the governing coalition. Twitter: @SmeRodina Location: Slovakia PRESS CONTACT Office [email protected] +421 910444676 Led by former Prime Minister Robert Fico, left-wing populist and nationalist party with a socially conservative and anti-immigration stance. Twitter: @SmerSk Location: Slovakia PRESS CONTACT Press office [email protected] Ľ Won the last election and is the largest party in the governing coalition. Non-standard party without fixed party structures. Twitter: @i_matovic Location: Slovakia PRESS CONTACT Peter Dojčan, media officer [email protected] Largest political party in terms of public support. Since the last election, it is represented by 11 deputies in Parliament. Location: Slovakia PRESS CONTACT Patrícia Medveď Macíková, spokesperson [email protected] +421 91716221 Social-liberal and populist party, one of the two largest political parties in Estonia. -

Laigualdaddegénero,Motordelcambio La Recuperación De La Crisis De La Covid Será También Una Prueba Para Los Derechos De La Mujer

La Vanguardia 08/03/21 Cod: 137545614 España Pr: Diaria Tirada: 65.922 Dif: 50.776 Pagina: 27 Secc: SOCIEDAD Valor: 30.891,02 € Area (cm2): 685,9 Ocupac: 69,42 % Doc: 1/1 Autor: Num. Lec: 480000 DÍAINTERNACIONALDELAMUJER Laigualdaddegénero,motordelcambio La recuperación de la crisis de la covid será también una prueba para los derechos de la mujer ste año tenemos un gramos liberar todo el poten- día internacional cial económico y empresarial de la Mujer espe- de las mujeres, nuestros esfuer- cial. No solo han zos de recuperación conduci- pasado exacta- rán a economías y sociedades Emente 110 años desde el primer más fuertes y resilientes. día internacional de la Mujer, En tercer lugar, debemos in- cuando más de un millón de tensificar nuestros esfuerzos mujeres y hombres unieron sus internacionales. Las mujeres y fuerzas y alzaron la voz por la las niñas suelen ser las prime- igualdad de derechos. ras víctimas durante las crisis. También estamos ante un Esto no fue diferente para esta importante punto de inflexión pandemia. La grave crisis de sa- el 8 de marzo de este año. Du- lud ha puesto de manifiesto la rante el año pasado, muchas de posiciónvulnerabledelasniñas nuestras vidas se han visto de- y las mujeres en muchas partes tenidas temporalmente por la del mundo, especialmente en peor crisis de salud en genera- los estados frágiles y afectados ciones. Al estar a la vanguardia por conflictos. Es importante en la lucha contra la pandemia que la nueva administración de en nuestros hospitales y resi- Estados Unidos vuelva a sen- dencias de ancianos, las muje- tarse con nosotros para comba- res se vieron afectadas de ma- tir, juntos, por los derechos de nera desproporcionada por la las niñas y las mujeres en todo pandemia; pagaron un precio el mundo. -

Monthly Forecast

July 2021 Monthly Forecast 1 Overview Overview 1 In Hindsight: the UNSC and Climate Change In July, France will have the presidency of the African issues anticipated in July include meet- 3 Status Update Security Council. Meetings are expected to be ings on: held in person this month. • DRC, on progress towards implementing the 5 Syria As a signature event of its presidency, France mandate of the UN Organization Stabilization 6 Democratic Republic of has chosen to convene a ministerial level brief- Mission in the DRC (MONUSCO); the Congo ing on preserving humanitarian space under the • West Africa and the Sahel, the biannual brief- 7 West Africa and the protection of civilians agenda item. Jean-Yves Le ing on the UN Office in West Africa and the Sahel Drian, France’s Minister for Europe and Foreign Sahel (UNOWAS); 9 Colombia Affairs, will chair the meeting. Secretary-Gener- • Libya, a ministerial-level briefing chaired by 11 Yemen al António Guterres; Robert Mardini, the Direc- the French Minister for Europe and Foreign 12 Libya tor-General of the International Committee of Affairs, Jean Yves Le Drian, on the UN Sup- the Red Cross; and Lucile Grosjean, the Del- port Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) and recent 13 Cyprus egate Director of Advocacy at Action Against developments; and 15 Preserving Hunger, are the anticipated briefers. • Darfur, on the drawdown and closure of Humanitarian Space The Council is planning to vote on a resolution the UN/AU Hybrid Operation in Darfur 16 Lebanon to renew the cross-border humanitarian assis- (UNAMID). 17 UNRCCA tance delivery mechanism in Syria, which expires The Council also expects to vote on a reso- 19 Sudan on 10 July. -

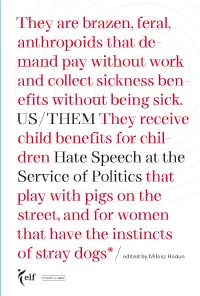

Here: on Hate Speech

They are brazen, feral, anthropoids that de- mand pay without work and collect sickness ben- efits without being sick. US / THEM They receive child benefits for chil- dren Hate Speech at the Service of Politics that play with pigs on the street, and for women that have the instincts of stray dogs * / edited by Miłosz Hodun LGBT migrants Roma Muslims Jews refugees national minorities asylum seekers ethnic minorities foreign workers black communities feminists NGOs women Africans church human rights activists journalists leftists liberals linguistic minorities politicians religious communities Travelers US / THEM European Liberal Forum Projekt: Polska US / THEM Hate Speech at the Service of Politics edited by Miłosz Hodun 132 Travelers 72 Africans migrants asylum seekers religious communities women 176 Muslims migrants 30 Map of foreign workers migrants Jews 162 Hatred refugees frontier workers LGBT 108 refugees pro-refugee activists 96 Jews Muslims migrants 140 Muslims 194 LGBT black communities Roma 238 Muslims Roma LGBT feminists 88 national minorities women 78 Russian speakers migrants 246 liberals migrants 8 Us & Them black communities 148 feminists ethnic Russians 20 Austria ethnic Latvians 30 Belgium LGBT 38 Bulgaria 156 46 Croatia LGBT leftists 54 Cyprus Jews 64 Czech Republic 72 Denmark 186 78 Estonia LGBT 88 Finland Muslims Jews 96 France 64 108 Germany migrants 118 Greece Roma 218 Muslims 126 Hungary 20 Roma 132 Ireland refugees LGBT migrants asylum seekers 126 140 Italy migrants refugees 148 Latvia human rights refugees 156 Lithuania 230 activists ethnic 204 NGOs 162 Luxembourg minorities Roma journalists LGBT 168 Malta Hungarian minority 46 176 The Netherlands Serbs 186 Poland Roma LGBT 194 Portugal 38 204 Romania Roma LGBT 218 Slovakia NGOs 230 Slovenia 238 Spain 118 246 Sweden politicians church LGBT 168 54 migrants Turkish Cypriots LGBT prounification activists Jews asylum seekers Europe Us & Them Miłosz Hodun We are now handing over to you another publication of the Euro- PhD. -

(Lithuania), Arturs Krišjānis Kariņš (Latvia), Kaja Kallas (Estonia) and Mateusz Morawiecki (Poland) on the Hybrid Attack on Our Borders by Belarus

Statement of the Prime Ministers Ingrida Šimonytė (Lithuania), Arturs Krišjānis Kariņš (Latvia), Kaja Kallas (Estonia) and Mateusz Morawiecki (Poland) on the hybrid attack on our borders by Belarus. We, the Prime Ministers of Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Poland, express our grave concern regarding the situation on the borders of Lithuania, Latvia and Poland with Belarus. It is clear to us that the ongoing crisis has been planned and systemically organized by the regime of Alexander Lukashenka. Using immigrants to destabilize neighbouring countries constitutes a clear breach of the international law and qualifies as a hybrid attack against the Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and thus against the entire European Union. In such situation, unprecedented for our region, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Poland value the clear commitment by the EU and it’s Member States to stand together in protecting the EU’s external border. Unity and urgent diplomatic, financial and technical support by the EU and its Member States is key to responding effectively to the challenge posed by the Lukashenka´s regime. It is equally important to jointly use all available diplomatic and practical means to cut the new irregular migration routes at its inception, as soon as possible. In the EU we need to use this momentum to rethink our approach towards the protection of our borders. We firmly believe that the protection of European external border is not just the duty of individual Member States but also the common responsibility of the EU. Hence, proper political attention should be paid to it on the EU level and sufficient funding allocated. -

Citizens Are Still Fond of ‘Europe’: Its Values, Culture and Social Model

PROGRAMME The European Young Leaders Class of 2017 will meet for the Drst time from 16 to 18 March 2017 in Portugal. The seminar takes place almost 60 years to the day since six governments signed the Treaty of Rome, the founding agreement of what would later become the European Union. The Treaty put in place the principles of free movement of labour, goods, services and capital. It also launched Europe on a journey – of varying pace – towards closer integration of its governments and peoples, through a series of treaties and agreements. But since the Lisbon Treaty was signed in 2007, progress has faltered – and even been reversed. There have been no more treaties; the United Kingdom has voted to leave the EU; and the ‘four freedoms’ have been put in question. Is the whole project under threat? Europe’s challenges are many and complex – but not insuperable. Most European citizens are still fond of ‘Europe’: its values, culture and social model. But they lack trust in its leaders, whom they see as disconnected from their daily reality and unable to tackle the challenges Europe faces. The prime objective of the seminar is to create bonds of trust between the young leaders so as to stimulate collaborative actions between them for the better of the EU and our societies. The European project is under threat from the rise of populism and post-fact politics. But can Europe use this crisis to change and focus on improving how it works, on educating people about the basic principles, on delivering tangible results and better communicating its successes? And while there is currently an atmosphere of doom sown by acts of terrorism, uncertainty about the United States’ stances on global issues such as defence, trade and climate change under Donald Trump, and threats to the liberal democratic order, the European Union remains a historically successful project. -

PLAYING OINA with the Romanian Presidency

PLAYING OINA WITH the Romanian Presidency 1 Table of contents INTERVIEW OF Siegfried Muresan, MEP (EPP) ` 47 PRIORITIES OF THE Romanian PRESIDENCY 810 POLITICAL CALENDAR FOR THE NExT SIx MONTHS 1011 wHAT ABOUT Romania? 1217 Some useful words 18 Let's play OinA! 19 3 relationship between the EU and the UK. Climate change is a crucial global challenge INTERVIEW OF Siegfried MureSan This new relationship, which will probably that asks for a European solution for the be a trade agreement, should guarantee future of our planet. My political family, the Romanian EPP MEP ` that the interests of EU citizens and EPP, is very much aware of the challenges businesses are preserved. we are facing in terms of global warming Hot Topics and CO2 emissions. We believe that Europe Last October, the Intergovernmental must engage with its international partners On November 14th, the European Panel on Climate Change released a very to internationally binding climate change Parliament adopted its position on the alarming report highlighting a number of agreements and invest in innovative, safe, Multinational Financial Framework (MFF) climate change impacts that could be and sustainable low-carbon energy post 2020. At Council level, there are still avoided by limiting global warming to technologies that minimise our dependency remaining sticking points. What are the 1.5ºC compared to 2ºC. Global human- to fossil fuels. The reduction of CO2 ambitions of the Romanian Presidency caused emissions of CO2 would need to emissions is crucial, but must be done at a with regard to the adoption of the MFF fall by about 45% from 2010 levels by realistic pace and while protecting post 2020? Would its adoption still be 2030, reaching ‘net zero’ around 2050.