US Anti-Apartheid Activism and Civil Rights Memory Submitted By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Celebration Nile Rodgers & CHIC

honoring Daniel Stern “REMEMBER TO PLAY AFTER EVERY STORM!” founder, reservoir capital group VISIONARY AWARD Mattie J.T. Stepanek Jeni Stepanek, Ph.D. executive director, mattie j.t. stepanek foundation come... join the family MATTIE J.T. STEPANEK PEACEMAKER AWARD Sting & Trudie Styler HUMANITARIAN AWARD HOSTED BY Rosie Perez and Touré WITH A CONCERT FEATURING Sting 2012 celebration Nile Rodgers & CHIC 6:30 pm cocktails gala 2.0 7:30 pm dinner, live auction & concert manhattan center’s hammerstein ballroom 311 WEST 34TH STREET, NEW YORK CITY thursday | january 31, 2013 to benefit the We Are Family Foundation www.wearefamilyfoundation.org www mahmoud jabari 2008 global teen leader chic & hip attire BOARD OF DIRECTORS & OFFICERS Jeffrey Hayzlett Global Business Celebrity, Bestselling Author, Sometimes Cowboy Nile Rodgers We Are Family Foundation Founder & Chairman Tommy Hilfiger Principle Designer, Tommy Hilfiger Corporate Mark Barondess Miller Barondess, LLP Vice Chairman John Hunt Founder & Chairman, Archimedia Nancy Hunt We Are Family Foundation President Jamal Joseph Professor of Film, Columbia University & Founder, Impact Repertory Theater Lauren Lewis We Are Family Foundation Executive Vice President Henry Juszkiewicz Chairman & CEO, Gibson Guitar Corp. Christopher Cerf Co-Founder & President, Sirius Thinking, Ltd. Vice President Albert H. Konetzni, Jr. Vice Admiral (Ret.), VP, Oceaneering International Inc. Michael Levine, Ph.D. Executive Director, The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop Treasurer Mitchell Kriegman Writer Daniel Crown President, Foray Entertainment & Partner, Red Crown Productions Secretary Curtis Mack Partner, McGuire Woods LLP William Margaritis Senior VP, FedEx Corporation Kim Brizzolara Film Producer & Investor Tod Martin President & CEO, Unboundary Judith E. Glaser CEO, Benchmark Communications, Inc. -

Interview with Otis Cunningham Danny Fenster

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Chicago Anti-Apartheid Movement Oral Histories Fall 2009 Interview with Otis Cunningham Danny Fenster Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_caam_oralhistories Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, African Languages and Societies Commons, American Politics Commons, Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Cultural History Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, International Relations Commons, Other Political Science Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Political History Commons, Political Theory Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the Work, Economy and Organizations Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Fenster, Danny. "Interview with Otis Cunningham" (Fall 2009). Oral Histories, Chicago Anti-Apartheid Collection, College Archives & Special Collections, Columbia College Chicago. http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_caam_oralhistories/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Oral Histories at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago Anti-Apartheid Movement by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. Transcription: Danny Fenster 1. Interviewer: Danny Fenster 2. Interviewee: Otis Cunningham 3. Date: 12112/09 4. Location: Otis's home in the Beverly neighborhood on Chicago's southwest side. 5. 20 years of activism 6. Activism in Chicago 7. Otis YOB: 1949, Chicago born and raised 8. Father and Mother both born in Chicago 9. Otis Cunningham: ... Probably sixth grade or so. Fifth grade or so. Because see 10. I was born in '49. So--uh, urn, I'm, uh, five years old when Brown versus Board 11. -

FOI Herald 5

ALL THE INFORMATION art FREEDOM of THAT IS FIT TO human rights poetry KNOW politics film INFORMATION freedom dialogue future Published by FOI Artisans HERALD O‘AHU EVENTS ❘ MARCH 14 – APRIL 2, 2005 RELATED Diverse Collaborative Effort Blossoms into EVENTS Monday, March 14 through March 18 Multimedia Events KHON-TV ACTIONLINE unique collaboration This one-time only promo- ON FREEDOM OF Abetween artists, writers, tional paper will give you the INFORMATION journalists, poets, filmmakers, scoop on events which will QUESTIONS non-profits and academics, stimulate your mind, nourish 11am-1pm. If you have a results in things you need to your soul and you will have problem or question about know about what matters. lots of fun discussing ideas, getting access to government They use their talents to reflecting on art, on politics, records or meetings, call express perspectives on the on freedom, on human rights, KHON-TV’s Actionline at importance of ‘the right to on our future together and 808-521-0222. Info: know’. It’s serious stuff – lots more. So open up the 808-748-0880. Sponsored by defending and protecting rights paper and we will see you at Honolulu Community Media cannot be taken for granted. the events. Council. Friday, March 18 HUMAN RIGHTS DAY AT HAWAI‘I Freedom of Information Day March 16th! STATE CAPITOL reedom of Information decision-making power. Hawai‘i Uniform tal accountability through 9am–5pm. Information, FDay is celebrated national- Govern-mental agencies exist Information and a general policy of access Education and human rights ly each year on March 16th to to aid the people in the forma- Practices Act (excerpt) to government records; afternoon panel. -

Fitchburg State University Today Newsletter for March 30 2015

Print Fitchburg State University Today March 30, 2015 - Vol 5, Issue 14 In This Issue Connors to chair Board of Trustees Connors to chair BOT Martin F. Connors Jr., Fiorentino Foyer dedicated president and chief executive officer of Food pantry opens at Hammond Rollstone Bank & Trust Women's History Month continues in Fitchburg, was elected chairman of the ALFA offers Food for Thought on Fitchburg State March 31 University Board of Trustees at the group's Harrod Lecture to look at marathon recent meeting. He will succeed Carol T. Community Read continues Vittorioso, partner and Talk explores city's Italian- owner of the Vittorioso & Taylor law firm in American experience Leominster, whose term Violence in sports probed expires this year. The Crucible to be performed Connors, a member of the Fitchburg State Martin F. Connors Jr. FAVE featured by AASCU board since August 2007, previously held the post of vice chairman. Conflict Studies address coming in April "Marty will be a great leader, continuing to share his vision Comm Media lecture series and business acumen with the university community as we launch our next chapter," said President Robert V. Antonucci, resumes who is retiring in June. Connors, a resident of Leominster, was Speaker Series resumes a member of the search committee that recommended Dr. Richard S. Lapidus to become the university's next president. Teaching opportunities in GCE "I know President Lapidus will benefit from Marty's counsel as much as I have." GCE Info Session on April 16 "I am honored by the trust my colleagues have placed in me Remembering Danny Schechter with this appointment," Connors said after the vote. -

Played by the Mighty Wurlitzer the Press, the CIA, and the Subversion of Truth

CHAPTER 6 Played by the Mighty Wurlitzer The Press, the CIA, and the Subversion of Truth Brian Covert A journalist in the US specializing in national security issues, Ken Dilanian, found himself under the harsh glare of the media spotlight in September 2014, when it was revealed that he had been collabo- rating with press officers of the United States government’s Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in the shaping and publishing of his news stories for the Los Angeles Times, one of the most influential daily newspapers in the nation. An exposé by the Intercept online magazine showed how, in pri- vate e-mail messages to CIA public affairs staff, Dilanian had not only shared entire drafts of his stories with the agency prior to publication, but had also offered to write up for the CIA on at least one occasion a story on controversial US drone strikes overseas that would be “reas- suring to the public” and “a good opportunity” for the CIA to put its spin on the issue.1 And Dilanian was not alone. Other e-mail messages, though heavily redacted by the CIA, showed that reporters from other major US news organizations likewise had cooperative relationships with the agency. Meanwhile, across the Atlantic Ocean that same month, a veteran journalist in Germany was blowing the whistle on his own profes- sion. Udo Ulfkotte, a former news editor with the Frankfurter Allge- meine Zeitung, one of the largest newspapers in Germany, revealed how he had cooperated over the years with the German Federal Intel- ligence Service and the CIA itself in the planting -

Anti-Apartheid Solidarity in United States–South Africa Relations: from the Margins to the Mainstream

Anti-apartheid solidarity in United States–South Africa relations: From the margins to the mainstream By William Minter and Sylvia Hill1 I came here because of my deep interest and affection for a land settled by the Dutch in the mid-seventeenth century, then taken over by the British, and at last independent; a land in which the native inhabitants were at first subdued, but relations with whom remain a problem to this day; a land which defined itself on a hostile frontier; a land which has tamed rich natural resources through the energetic application of modern technology; a land which once imported slaves, and now must struggle to wipe out the last traces of that former bondage. I refer, of course, to the United States of America. Robert F. Kennedy, University of Cape Town, 6 June 1966.2 The opening lines of Senator Robert Kennedy’s speech to the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS), on a trip to South Africa which aroused the ire of pro-apartheid editorial writers, well illustrate one fundamental component of the involvement of the United States in South Africa’s freedom struggle. For white as well as black Americans, the issues of white minority rule in South Africa have always been seen in parallel with the definition of their own country’s identity and struggles against racism.3 From the beginning of white settlement in the two countries, reciprocal influences have affected both rulers and ruled. And direct contacts between African Americans and black South Africans date back at least to the visits of American 1 William Minter is editor of AfricaFocus Bulletin (www.africafocus.org) and a writer and scholar on African issues. -

Be Inspired. Be Informed. the Tierra Solution Resolving Climate Change Through Monetary Transformation New in by Frans C

Be inspired. Be informed. The Tierra Solution Resolving Climate Change Through Monetary Transformation New in By Frans C. Verhagen Foreword by Felix Dodds May osimo was inspired by Cosimo de Medici, the first of the de Medici dynasty, who ignited the most important cultural and artistic revolution in Western history—the Renaissance.This quest for enrichment is the foundation for Cosimo, and is 2012 reflected in the work that we do for our authors and their audiences. Cosimo’s mission is to create a smart and sustainable society by connecting people with valuable ideas. We offer authors and organizations full publishing support, while using “A visionary and im- Cthe newest technologies to present their works in the most timely and effective way. mensely practical ap- proach to reforming Our Customers include: Mission Statement today’s bubble finance Authors Our mission is to create a smart and sustainable society by and taming its global Academic Audiences connecting people with valuable ideas. We offer authors casino. Verhagen [...] Bookstores (Online, College and Independent) and organizations full publishing support, while using the illuminates the win-win Libraries and other institutions newest technologies to present their works in the most solutions possible when Avid readers around the world timely and effective way. we combine monetary Specifications transformation with low-carbon, renewable Imprints resource strategies and B&W 6 x 9” (229 x 152 mm) equitable approaches 374 Cosimo Books offers fine books by independent authors Cosimo Classics brings to life unique and rare classics, to sustainable develop- Paperback that inspire, inform, and engage readers on a variety of subjects, representing a wide range of subjects that include Business, including Personal Development, Socially Responsible Business, Economics, History, Personal Development, Philosophy, ment.” - Hazel Henderson, President and Economic and Public affairs. -

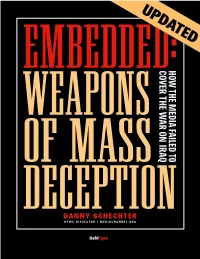

Weapons of Mass Deception

UPDATED. EMBEDDEDCOVER THE WAR ON IRAQ HOW THE TO MEDIA FAILED . WEAPONS OF MASS DECEPTIONDANNY SCHECHTER NEWS DISSECTOR / MEDIACHANNEL.ORG ColdType WHAT THE CRITICS SAID This is the best book to date about how the media covered the second Gulf War or maybe miscovered the second war. Mr. Schecchter on a day to day basis analysed media coverage. He found the most arresting, interesting , controversial, stupid reports and has got them all in this book for an excellent assessment of the media performance of this war. He is very negative about the media coverage and you read this book and you see why he is so negative about it. I recommend it." – Peter Arnett “In this compelling inquiry, Danny Schechter vividly captures two wars: the one observed by embedded journalists and some who chose not to follow that path, and the “carefully planned, tightly controlled and brilliantly executed media war that was fought alongside it,” a war that was scarcely covered or explained, he rightly reminds us. That crucial failure is addressed with great skill and insight in this careful and comprehensive study, which teaches lessons we ignore at our peril.” – Noam Chomsky. “Once again, Danny Schechter, has the goods on the Powers The Be. This time, he’s caught America’s press puppies in delecto, “embed” with the Pentagon. Schechter tells the tawdry tale of the affair between officialdom and the news boys – who, instead of covering the war, covered it up. How was it that in the reporting on the ‘liberation’ of the people of Iraq, we saw the liberatees only from the gunhole of a moving Abrams tank? Schechter explains this later, lubricious twist, in the creation of the frightening new Military-Entertainment Complex.” – Greg Palast, BBC reporter and author, “The Best Democracy Money Can Buy.” "I'm your biggest fan in Iraq. -

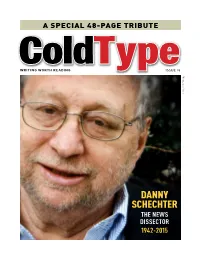

DANNY SCHECHTER Schechter, Danny Died on March 19, in New York City

1/30/2019 DANNY SCHECHTER Obituary: DANNY SCHECHTER’s Obituary by the Boston Globe. DANNY SCHECHTER Schechter, Danny Died on March 19, in New York City. Danny Schechter, aka "The News Dissector" aka "troublemaker," grew up in the Bronx, in the progressive, union-sponsored Amalgamated Houses. His immigrant grandparents were garment workers who brought their socialist ideals with them from the Old Country. His mother, Ruth Lisa Schechter, was a secretary who became a poet. His father, Jerry Schechter, was a pattern-maker who became a sculptor. Danny attended DeWitt Clinton H.S., where he served as the editor-in-chief of the legendary Clinton News. From there it was on to Cornell, Syracuse, the London School of Economics, and Harvard as a Neiman Fellow. But this is only a small part of his life's journey. He joined the Northern Student Movement in high school and became actively involved in the Civil Rights Movement, going down to Mississippi in 1964. He became a leader in the movement to end the Vietnam War, was a member of SDS and began a lifelong commitment to South Africa in 1967 as an original member of the "London Recruits." He fought tirelessly against Apartheid from then on. Danny never hesitated to put his convictions on the line. In the 1970s, he turned back to his first love—journalism–and became the "news dissector" at radio station WBCN in Boston. He wove news and music together in collages that not only reported the day's events but also helped explain how the world worked. -

Danny Schechter the News Dissector 1942-2015 2 Remembering Danny Schechter

A SPECIAL 48-PAGE TRIBUTE ColdType WRITING WORTH READING ISSUE 96 Photo: Joyce Ravid Joyce Photo: DANNY SCHECHTER THE NEWS DISSECTOR 1942-2015 2 Remembering Danny Schechter Go Higher At the end of a year there’s a sigh welling from within What was done, undone? How have we changed? Save the ravages of age? When you see too much, You think you know too much My challenge: Can I feel more Think less? What next to work for And become Open to change within? Is the die cast? Has the journey become The destination? Tick, tick, tick… Is it over before it’s over? I feel estranged in two countries with only dreams to remember A moment for reflection erupts Staring off, I stare within There is a pause A silence too As days grown shorter And nights darker Only to say, unexpectedly Light smiled into my world and helped me Go higher Danny Schechter 31 December 2012 ColdType | www.coldtype.net Remembering Danny Schechter 3 News Dissector at work, WBCN. Hamba Kahle, Comrade By Tony Sutton, ColdType editor ’ve worked on many projects with Danny than reading his words, I just couldn’t start Schechter during the past 12 years, producing editing until . well, you know when. seven of his books and publishing his essays Sadly, work on Topic is now under way, and Iand columns in ColdType. However, unlike ev- it’s like everything Danny and I have worked erything before, this special edition of ColdType on before: precise, meticulous, funny, serious. is one I’ve been dreading over the too-short six Indispensable. -

Apartheid Whitewash - South Africa Propaganda in the United States

Apartheid Whitewash - South Africa Propaganda in the United States http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.af000257 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Apartheid Whitewash - South Africa Propaganda in the United States Alternative title Apartheid Whitewash - South Africa Propaganda in the United States Author/Creator Leonard, Richard Contributor Davis, Jennifer Publisher Africa Fund Date 1989 Resource type Pamphlets Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa, United States Coverage (temporal) 1975 - 1989 Source Africa Action Archive Rights By kind permission of Africa Action, incorporating the American Committee on Africa, The Africa Fund, and the Africa Policy Information Center. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the More You Watch the Less You Know News Wars(Sub)Merged Hopesmedia Adventures by Danny Schechter the More You Watch the Less You Know

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The More You Watch the Less You Know News Wars(sub)Merged HopesMedia Adventures by Danny Schechter The More You Watch the Less You Know. by Robert McChesney and Danny Schechter. Foreword by Jackson Browne and Robert W. McChesney. A candid insider's tale of how the media really works and why it doesn't work the way it should, The More You Watch, The Less You Know has emerged as a key catalyst in the debate on media reform. Since its original release, after more than a hundred television and radio author interviews and countless print reviews and features, The More You Watch, The Less You Know has achieved the near impossible: it has brought the crisis in television news out into the open, gotten it discussed on the very television news programs it critiques, and pretty much everywhere else as well, on the airwaves and off. The More You Watch, The Less You Know recounts Schechter's media adventures, from when he was "Danny Schechter the News Dissector" on Boston's WBCN radio, to his stints as a producer at ABC's 20/20 and CNN, to his personal odyssey chronicling the anti-Apartheid revolution in South Africa, to his development of innovative programming like South Africa Now and Rights & Wrongs as an independent producer. In this age of telecommunications bills and media mergers, The More You Watch, The Less You Know is an insider’s passionate plea for freedom of the (electronic) press. Buying options. “In the era of the incredibly shrinking sound bite .