Recent Publications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Park Ave Noise Assessment

Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Proposed Emergency Ventilation Plant for the Lexington Avenue Subway Line between the 33rd Street/Park Avenue South Station and the Grand Central Station/42nd Street Station July 2017 MTA New York City Transit Proposed Emergency Ventilation Plant Lexington Avenue Subway Line This page intentionally blank. MTA New York City Transit Proposed Emergency Ventilation Plant Lexington Avenue Subway Line COVER SHEET Document: Final Environmental Impact Statement Project Title: Proposed Emergency Ventilation Plant for the Lexington Avenue Subway Line between 33rd Street/Park Avenue South Station and the Grand Central Terminal/42nd Street Station Location: The Proposed Emergency Ventilation Plant would be located in the streetbed of Park Avenue between East 36th Street and East 39th Street, New York City, New York County, New York Lead Agency: Metropolitan Transportation Authority New York City Transit (MTA NYCT), 2 Broadway, New York, NY 10004 Lead Agency Contact: Mr. Emil F. Dul P.E., Principal Environmental Engineer, New York City Transit, phone 646-252-2405 Prepared by: Michael Tumulty, Vice President STV Group; Steven P. Scalici, STV Group; Patrick J. O’Mara, STV Group; Douglas S. Swan, STV Group; Niek Veraart, Vice President, Louis Berger; G. Douglas Pierson, Louis Berger; Leo Tidd, Louis Berger; Jonathan Carey, Louis Berger; Steve Bedford, Louis Berger; Allison Fahey, Louis Berger; Cece Saunders, President, Historical Perspectives, Inc.; Faline Schneiderman, Historical Perspectives, Inc. Date of -

Historic Murray Hill Walking Tour

AN ARCHITECTURAL WALKING TOUR OF MURRAY HILL HE TOUR BEGINS on the south side of the intersection of an iron fence on the 35th Street side. The 1864 brownstone struc- 23. 149 East 36th Street. A distinctive Georgian style house with TPark Avenue and 37th Street. See #1 on map to begin tour. ture is distinguished by the high arched bays and arched entrance circular-headed multi-paned windows on the parlor floor. An asterisk ( ) next to the number indicates that the building is a porch. The spire was added in 1896. The church interior features 24. 131 East 36th Street. A brownstone converted into a Parisian New York City* Landmark; the year of designation is also included. stained-glass windows by William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones, townhouse by the famous owner/architect William Adams Delano. 1. “Belmont,” Robert Murray House Site. The two-story stone Louis Comfort Tiffany and John La Farge; the oak communion It is characterized by the tall French doors on the second floor and house stood until a fire in 1835, facing east on the present intersec- rail was carved by Daniel Chester the rusticated faux stone at the ground floor. French. tion of Park Avenue and 37th Street. Verandas ran around three 25. 125 East 36th Street. This well preserved narrow brownstone 11. sides of the Georgian-style building and from a roof deck one could * The Collectors Club, 22 East was the first home of newlyweds Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, see a magnificent view of Manhattan. The grounds were sur- 35th Street (New York City who moved in following their European honeymoon in 1905. -

Stage IA Archaeological Assessment for the 37Th Street Ventilation Facility, East Side Access

September 2007 Prepared for: MTACC Stage IA Archaeological Assessment for the 37th Street Ventilation Facility, East Side Access New York City, New York Prepared by: Burlington, New Jersey Stage IA Archaeological Assessment for the 37th Street Ventilation Facility, East Side Access New York City, New York Prepared for: MTACC 2Broadway NewYork,NewYork Prepared by: Ingrid Wuebber and Edward Morin, RPA URS Corporation 437 High Street Burlington, New Jersey 08016 609-386-5444 September 2007 STAGE IA ASSESSMENT FOR THE 37TH STREET VENTILATION FACILITY,EAST SIDE ACCESS Abstract URS Corporation conducted a Stage IA archaeological assessment in support of the construction of a proposed 37th Street Ventilation Facility as part of the East Side Access Project, located in the borough of Manhattan. Two options have been proposed for the ventilation facility location. The first option would locate it within the sidewalk on both the northwest and southwest corners, at the intersection of 37th Street and Park Avenue. The second option would locate the facility within the sidewalk on the southwest corner, at the intersection of 37th Street and Park Avenue. The goal of the study was to provide information on the potential for the two project areas to contain intact and original soil surfaces. This information was needed in order to determine if proposed construction activities would extend to a depth that would encounter intact prehistoric and/or historic surfaces that may contain archaeological resources. Background research indicated that pre-European sites on Manhattan are not common, as subsequent development has obliterated them. This appears to be the case in the project area. -

Murray Hill for Family Living - Nytimes.Com

11/17/2014 Murray Hill for Family Living - NYTimes.com http://nyti.ms/1vHN8kg REAL ESTATE | LIVING IN Murray Hill for Family Living By ALISON GREGOR AUG. 13, 2014 A decade ago, when people asked Eve Moskowitz Parness where she lived, the Murray Hill resident frequently put them off with the vague answer “Midtown East.” Though she liked her Manhattan neighborhood, Ms. Parness said that, as a student, she was embarrassed to be associated with Murray Hill, particularly the bar scene on Third Avenue, with its reputation as a postgraduate playground. However, in the past few years, many more families with young children have been moving to Murray Hill. “I walk around, and all I see are people with baby strollers,” said Ms. Parness, who has a toddler and lives in a two-bedroom apartment she bought with her husband in 2012. The change has not gone unnoticed by longtime residents, said Diane G. Bartow, the president of the Murray Hill Neighborhood Association, who has lived there for more than 30 years. “For about the last three years, there’s been a big change in the demographics of the area,” she said. In addition to the young college graduates, “it was a population that skewed older, but now we’re seeing a lot of families with little children moving to the area, staying in the area.” Murray Hill runs from 40th Street down to about 27th Street, and from Fifth Avenue over to the East River, according to the neighborhood association. The small Murray Hill Historic District between Lexington and Park Avenues is largely 19th-century brownstones and rowhouses, while Park Avenue has towers with co-ops and high-end rental apartments. -

Murray Hill Historic District Extension Document 2004

MURRAY HILL HISTORIC DISTRICT EXTENSIONS Designation Report New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission March 30, 2004 MURRAY HILL HISTORIC DISTRICT EXTENSIONS Designation Report Essay researched and written by Gale Harris & Donald G. Presa Building entries researched and written by Donald G. Presa Research assistance by Elizabeth Drew and Collin Sippel Photographs by Carl Forster Map by Kenneth Reid Research Department Mary Beth Betts, Director Ronda Wist, Executive Director Mark Silberman, Counsel Brian Hogg, Director of Preservation ROBERT B. TIERNEY, Chair PABLO E. VENGOECHEA, Vice-Chair JOAN GERNER THOMAS PIKE ROBERTA BRANDES GRATZ JAN HIRD POKORNY MEREDITH J. KANE ELIZABETH RYAN CHRISTOPHER MOORE VICK I M ATCH SUNA SHERIDA PAULSEN Commissioners On the front cover: 114 East 36th Street (Photo: Carl Forster, 2004) TABLE OF CONTENTS MAP ........................................................................1 MURRAY HILL HISTORIC DISTRICT EXTENSIONS BOUNDARIES .................2 TESTIMONY AT THE PUBLIC HEARING ........................................3 SUMMARY ..................................................................4 ESSAY: Historical and Architectural Development of the Murray Hill Historic District The Murray Hill Neighborhood .............................................6 Building Within the Murray Hill Historic District Extensions, 1856-1869 . 10 The 1870s and 80s ......................................................12 The 1890s .............................................................14 Early Twentieth Century -

Murray Hill 2014

2014 A publication of the Murray Hill Neighborhood Association Murray Hill No. 2 …to continue to make Murray Hill a highly desirable place to live, work and visit. ife Fall Street Fair 2014L Another Big Success! By Tom Horan, Vice President, MHNA, and Street Fair Chair Just the right combination of moderate would love to have more Murray Hill everyone who helped make this event temperature, low humidity, and abun- artisans at the Fair. such a resounding success - especially dant sunshine Our musical entertainment was the volunteers who came early and provided won- really top-notch this year. Per- stayed late. derful weather formers entertained us with ev- We will begin to plan next year’s Fair for the Murray erything from Blues to Jazz to soon, so make your plans now to join Hill Street Fair Rock to solo vocals and even us next Spring on Park Avenue! on June 7th. some Big Band selections. Many It was a really attendees grabbed a snack and spectacular pulled up a chair to sit and en- day and the joy the music for a while before Fair was a great success. moving on to peruse the various mer- The retail attendees this year included chant offerings. a large number of arts and crafts ven- As is always the case, there were doz- dors offering unique and beautiful ens of food ven- handcrafted items. We hope dors to select to increase the presence of from. This year’s this type of vendor in fu- ture events, so watch for an- favorites seemed nouncements and informa- to be the Ger- tion on joining us at the Fair man bratwurst if you would like to partici- and The Pickle pate or know someone who Man. -

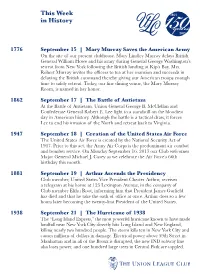

This Week in History

This Week in History 1776 September 15 | Mary Murray Saves the American Army On the site of our present clubhouse, Mary Lindley Murray delays British General William Howe and his army during General George Washington’s retreat from New York following the British landing at Kip’s Bay. Mrs. Robert Murray invites the officers to tea at her mansion and succeeds in delaying the British command thereby giving our American troops enough time to safely retreat. Today, our fine dining venue, the Mary Murray Room, is named in her honor. 1862 September 17 | The Battle of Antietam At the Battle of Antietam, Union General George B. McClellan and Confederate General Robert E. Lee fight to a standstill on the bloodiest day in American history. Although the battle is a tactical draw, it forces Lee to end his invasion of the North and retreat back to Virginia. 1947 September 18 | Creation of the United States Air Force The United States Air Force is created by the National Security Act of 1947. Prior to this act, the Army Air Corps is the predominant air combat and bomber service. On Monday September 16, 2013 our Club welcomes Major General Michael J. Carey as we celebrate the Air Force’s 66th birthday this month. 1881 September 19 | Arthur Ascends the Presidency Club member, United States Vice President Chester Arthur, receives a telegram at his home at 123 Lexington Avenue, in the company of Club member Elihu Root, informing him that President James Garfield has died and that he take the oath of office at once. -

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 20, 2011, Designation List 448 LP-2426

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 20, 2011, Designation List 448 LP-2426 MADISON BELMONT BUILDING, FIRST FLOOR INTERIOR, consisting of the main lobby space and the fixtures and components of this space, including but not limited to, wall, ceiling and floor surfaces, entrance and vestibule doors, grilles, bronze friezes and ornament, lighting fixtures, elevator doors, mailbox, interior doors, clock, fire command box, radiators, and elevator sign, 181-183 Madison Avenue (aka 31 East 33rd Street and 44-46 East 34th Street), Manhattan. Built: 1924-25; architects: Warren & Wetmore. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 863, Lot 60. On July 26, 2011, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a Public Hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Madison Belmont Building, First Floor Interior and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. There were three speakers in favor of designation including a representative of the owner and representatives of the Historic Districts Council and the Society for the Architecture of the City. There were no speakers in opposition. Summary The first floor interior lobby of the Madison Belmont Building is a rare, intact and ornate Eclectic Revival style space designed as part of the original construction of the building in 1924-25. The room is finished with a mixture of fine materials, including a variety of marbles and bronze and has a multi-colored, barrel-vaulted ceiling painted in classically-inspired designs. Reached via the main entrance and vestibule on 34th Street, it serves the Madison Belmont Building, an L-shaped structure running south to 33rd Street and east to Madison Avenue, which was designed by the prominent architectural firm of Warren & Wetmore, with ironwork in the Art Deco style by Edgar Brandt, French iron master.