That David Copperfield Kind of Crap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens Chapter 13 (Excerpt)

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens Chapter 13 (Excerpt) My aunt’s handmaid, as I supposed she was from what she had said, put her rice in a little basket and walked out of the shop; telling me that I could follow her, if I wanted to know where Miss Trotwood lived. I needed no second permission; though I was by this time in such a state of con- sternation and agitation, that my legs shook under me. I followed the young woman, and we soon came to a very neat little cottage with cheerful bow-windows: in front of it, a small square graveled court or garden full of flowers, carefully tended, and smelling deliciously. “This is Miss Trotwood’s,” said the young woman. “Now you know; and that’s all I have got to say.” With which words she hurried into the house, as if to shake off the responsibility of my appearance; and left me standing at the garden-gate, looking disconsolately over the top of it towards the parlor window, where a muslin curtain partly undrawn in the middle, a large round green screen or fan fastened on to the windowsill, a small table, and a great chair, suggested to me that my aunt might be at that moment seated in awful state. My shoes were by this time in a woeful condition. The soles had shed themselves bit by bit, and the upper leathers had broken and burst until the very shape and form of shoes had departed from them. My hat (which had served me for a night-cap, too) was so crushed and bent, that no old battered handleless saucepan on a dunghill need have been ashamed to vie with it. -

List of Characters

LIST OF CHARACTERS David Copperfield Agnes Wickfield The protagonist and narrator of the novel. David is David’s true love and daughter of Mr. Wickfield. The innocent, trusting, and naïve even though he suffers calm and gentle Agnes admires her father and David. abuse as a child. He is idealistic and impulsive and Agnes always comforts David with kind words or remains honest and loving. Though David’s troubled advice when he needs support. childhood renders him sympathetic, he is not perfect. He often exhibits chauvinistic attitudes toward the Mr Wickfield lower classes. In some instances, foolhardy decisions mar David’s good intentions. Mr. Wickfield is a lawyer and business manager for both Miss Betsey and Mrs Strong, David’s new headmaster. Mr Wickfield is a kind and generous man, Clara Copperfield but suffers from an alcohol addiction. This taste for David’s mother. The kind, generous, and goodhearted alcohol later becomes increasingly difficult to control, Clara embodies maternal caring until her death, which leaving Mr Dick and his clients vulnerable to the occurs early in the novel. David remembers his mother manipulation of others. as an angel whose independent spirit was destroyed by Mr. Murdstone’s cruelty. Mrs Strong The kind and straight talking headteacher of the Peggotty school in Canterbury that David later joins, arranged David’s nanny and caretaker. Peggotty is gentle and by his aunt and Mr Wickfield. selfless, opening herself and her family to David whenever he is in need. She is faithful to David and his James Steerforth family all her life, never abandoning David, his mother, or Miss Betsey. -

David Copperfield: Victorian Hero

David Copperfield: Victorian Hero by James A. Hamby A Dissertation Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the College of Graduate Studies of Middle Tennessee State University Murfreesboro, Tennessee August 2012 UMI Number: 3528680 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. OiSi«Wior» Ftattlisttlfl UMI 3528680 Published by ProQuest LLC 2012. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Submitted by James A. Hamby in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, specializing in English. Accepted on behalf of the Faculty of the College of Graduate Studies by the dissertation committee: Date: Quaul 3-1.9J310. Rebecca King, Ph.D. ^ Chairperson Date:0ruu^ IX .2.612^ Elvira Casal^Ph.D. N * Second Reader f ./1 >dimmie E. Cain, Ph.D. Af / / / y # Third Reader / diPUt Date:J Tom Strawman, Ph.D. Chair, Department of English (lULa.lh Qtt^bate: 7 SI '! X Michael D.)'. Xllen, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Graduate Studies © 2012 James A. Hamby ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii For my family. -

Montclair State University Digital Commons Field

Montclair State University Montclair State University Digital Commons 2018-2019 Borders and Boundaries PEAK Performances Programming History 10-18-2018 Field Office of Arts + Cultural Programming PEAK Performances at Montclair State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.montclair.edu/peak-performances-2018-2019 Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons World Premiere! Liz Gerring Dance Company Field Photo by Rodrigo Vazquez Photo by Rodrigo October 18-21, 2018 Alexander Kasser Theater Dr. Susan A. Cole, President Daniel Gurskis, Dean, College of the Arts Jedediah Wheeler, Executive Director, Arts + Cultural Programming World Premiere! Liz Gerring Dance Company Field Choreographed by Liz Gerring Original Music Composed by Michael J. Schumacher Production Design by Robert Wierzel Associate Lighting Designer/Company Production Manager Amith A. Chandrashakar Assistant Lighting Designer Abigail Hoke-Brady Stage Manager Stephanie Byrnes-Harrell Rehearsal Assistants Brandon Collwes, Claire Westby Company Manager Elizabeth DeMent Dancers Brandon Collwes, Joseph Giordano, Forrest Hersey, Julia Jurgilewicz, Jamie Scott, Thomas Welsh-Huggins, Claire Westby Liz Gerring Dance Company is a program of TonalMotion Inc., a 501(c)3 nonprofit corporation. lizgerringdance.org Co-produced by Peak Performances @ Montclair State (NJ). Field was developed in residence at the Alexander Kasser Theater, Montclair State University, Montclair, NJ. Additional funding provided by Kirk Radke. Duration: 1 hour, no intermission. In consideration of both audiences and performers, please turn off all electronic devices. The taking of photographs or videos and the use of recording equipment are not permitted. No food or drink is permitted in the theater. Program Notes Field is the third work by Liz Gerring in the trilogy of large-scale proscenium works commissioned by Peak Performances at Montclair State University. -

David Copperfield: Personal History of David Copperfield: the Personal History of David Copperfield Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DAVID COPPERFIELD: PERSONAL HISTORY OF DAVID COPPERFIELD: THE PERSONAL HISTORY OF DAVID COPPERFIELD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Charles Dickens,H. K. Browne,Chris Barlow,Professor Jeremy Tambling | 1024 pages | 28 Jan 2005 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780140439441 | English | London, United Kingdom David Copperfield: Personal History of David Copperfield: The Personal History of David Copperfield PDF Book And, if he were politely underwhelmed by the wiry and breathless Micawber of Peter Capaldi who should have been one of the villains , he would without question rejoice in other performers—instinctive Dickensians like Tilda Swinton, Gwendoline Christie, and, most endearing of all, Hugh Laurie. With a wild corona of hair, flaring and blazing like the sun, Laurie takes the part of Mr. Anthony Lane has been a film critic for The New Yorker since Mr Spenlow Faisal Dacosta The life of David Copperfield is chronicled from his birth to now. Runtime: min. The Guardian. Trivia Filmed during the hot dry summer of , the film was finally premiered in Canada in September and theatrically released in the UK in January British theatrical release poster. From his unhappy childhood to the discovery of his gift as a storyteller and writer, David's journey is by turns hilarious and tragic, but always full of life, color and humanity. Wickfield Nikki Amuka-Bird as Mrs. Sign In. Glenn Kenny was the chief film critic of Premiere magazine for almost half of its existence. Hull Live. Download as PDF Printable version. Best Casting. British Independent Film Awards. She had nothing worse than a lone wolf. Will be used in accordance with our Privacy Policy. -

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens

Ch apter 1 In reading my story, you’ll decide whether I’m the hero of my own life or someone else is. I was born at Blunderstone in Suffolk. My father, David, had died six months before, at the age of thirty-nine. His aunt, Betsey Trotwood, was the head of the family. Aunt Betsey had been married to a younger man who had been very handsome and was said to have abused her. They had separated. Aunt Betsey had taken back her birth name, bought a seaside house in Dover, established herself there as a single woman with one servant, and lived in near-seclusion. It was believed that her husband had gone to India and died there ten years later. My father had been a favorite of Aunt Betsey until his marriage, which had deeply offended her. She never had met my mother, Clara. However, because my mother had been only nineteen when she married my father, then thirty- eight, Aunt Betsey had taken offense and referred to my mother as a “wax doll.” My father and Aunt Betsey had never seen each other again. The day before I was born was a bright, windy March day. My mother was in poor health and in low spirits. Dressed in mourning because of my father’s 1 2 CHARLES DICKENS recent death, she sat in the parlor by the fi re shortly before sunset. When she lifted her sad eyes to the window opposite her, she saw an unfamiliar lady coming up the walk. The lady was Aunt Betsey. -

David Copperfield

THE PERSONAL HISTORY OF DAVID COPPERFIELD 30 min Schools Script THE PERSONAL HISTORY OF DAVID COPPERFIELD Play by David Schneider, Armando Iannucci and Simon Blackwell Based on the screenplay by Armando Iannucci and Simon Blackwell and the novel by Charles Dickens All our performers mingle on stage, chatting in character. There’s a lectern to one side of the stage. A few wooden chairs and a table are set out to suggest a living room. NARRATOR DAVID enters, smartly dressed, holding an old- fashioned manuscript book. The performers applaud him and take seats at the sides of the stage where they remain watching except when performing in a scene. The heavily pregnant CLARA takes a seat on one of the chairs in the “living room”. Narrator David goes to the lectern, opens his book and starts to read. NARRATOR DAVID To begin my life with the beginning of my life. Clara lets out a really loud moan. She’s in labour. CLARA AAAAAAAAAAAARGH! PEGGOTTY!!! PEGGOTTY gets up from the seats at the side and rushes around looking for something, including in the audience. PEGGOTTY Peggotty’s coming! As promised! Peggotty promisey. With you in 13 seconds!.. Aha! She finds what she’s looking for: some towels, hidden under one of the seats in the front row. Clara lets out another moan and Peggotty joins her with the towels. CLARA AAAAAAARGH! PEGGOTTY Try to pretend it doesn’t hurt. CLARA But it do-AAAAAAAAAAAAAAGH-es! BETSEY TROTWOOD gets up from her seat, knocks at an imaginary door and opens it. One of the other performers makes the knocking noise with a percussion instrument. -

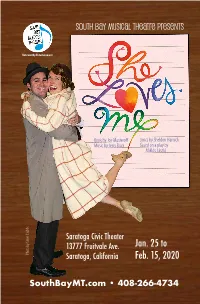

Jan. 25 to Feb. 15, 2020

South Bay Musical Theatre presents Noteworthy Entertainment Book by Joe Masteroff Lyrics by Sheldon Harnick Music by Jerry Bock Based on a play by Miklós László Saratoga Civic Theater 13777 Fruitvale Ave. Jan. 25 to Photo by Steve Stubbs Steve by Photo Saratoga, California Feb. 15, 2020 SouthBayMT.com • 408-266-4734 1 There are plenty more delights to be discovered! Join us for the remaining shows of our 2019-2020 season! Director’s Note Up next, for one night only, is our salute to Stephen Sondheim’s 90th birthday, Songs I Wish I’d HE LOVES ME is often hailed as the “perfect and treated it as a play and dug deep into each Written (at least in part) by Brad Handshy, the creator of our popular Broadway By The Decade Scharming musical” I knew this to be true the character’s purpose and journey. For me, the series. In May, we open Rodgers & Hammerstein’s South Pacific, which won 10 Tony Awards when moment I first read it and said to myself, “Well, theme I most wanted to explore was simple: it was released 70 years ago. We conclude the season with an original Big Band tribute to The they sure don’t write them like this anymore.” You can find love in the most unexpected place Fabulous 40s: Songs of Love & War, featuring those — even if you’re a perfume store clerk in 1930’s wonderfully nostalgic melodies curated from The his comedic love story has truly stood the Budapest. To quote our Georg: “Will wonders Great American Songbook. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 56,1936-1937

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Branch Exchange Telephone, Ticket and Administration Offices, Com. 1492 FIFTY-SIXTH SEASON, 1936-1937 CONCERT BULLETIN of the Boston Symphony Orchestra INCORPORATED SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor RICHARD Burgin, Assistant Conductor with historical and descriptive notes By John N. Burk COPYRIGHT, 1936, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. The OFFICERS and TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Bentley W. Warren .... President Henry B. Sawyer Vice-President Ernest B. Dane Treasurer Allston Burr Roger I. Lee Henry B. Cabot Richard C. Paine Ernest B. Dane Henry B. Sawyer Alvan T. Fuller Pierpont L. Stackpole N. Penrose Hallowell Edward A. Taft M. A. De Wolfe Howe Bentley W. Warren G. E. Jui)D, Manager C. W. Spalding, Assistant Manager [305] . Old Colony Trust Company 17 COURT STREET, BOSTON The principal business of this company is 1 Investment of funds and management of property for living persons. 2. Carrying out the provisions of the last will and testament of deceased persons. Our officers would welcome a chance to dis- cuss with you either form of service. <tAllied with The First National Bank 0/" Boston [306] Contents Title Page page 305 Programme ......... 309 Analytical Notes: Bach: Toccata in C major for Organ . 311 (Orchestrated by Leo Weiner) Hindemith: Symphony "Mathis der Maler" . 320 Kalinnikov: Symphony No. i in G minor . 343 Entr'actes Burkhard: The Isenheim Altar of Matthias Griineivald 331 Dreyfus: Notes on Conducting. Conversations with Koussevitzky ....... 338 Announcement to the "Friends of the Boston Sym- phony Orchestra" ....... 332-333 The Next Programme . 351 A Lost Symphony Restored . -

The Personal History of David Copperfield

THE PERSONAL HISTORY OF DAVID COPPERFIELD How to put on a star production at school SCHOOLS STARTER KIT INTRODUCTION This year, to raise money for BBC Children in Need, we’re giving you a bit of Hollywood sparkle! Hitting the big screens soon is the ‘The Personal History of David Copperfield’, starring big names such as Dev Patel and Daisy May Cooper, directed by the acclaimed Armando Iannucci. Adapted from the classic novel ‘David Copperfield’ by Charles Dickens, the film is an adaptation of the inspiring rags to riches story, based on Dickens’s early life experiences. We’re offering you an exclusive 30-minute abridged version of the script, which has been has been specially developed for schools so that you can stage a play and deliver a star performance for your parents, friends and teachers. So, set the scene and make it a sell out performance to raise lots of money for disadvantaged children in the UK! In addition to the script, we’ve got all the tools you need to get going in this schools’ starter kit, including: 4 10 Steps to a Star Production 4 Story Context and Synopsis 4 List of characters 4 Guide to Production Roles 4 Event and Fundraising plan template 4 Guidance for Rehearsals 4 Rehearsal Timetable template 4 Ticket templates 4 Programme template 4 Event poster SO WHAT ARE YOU WAITING FOR? GET TOGETHER, GET PLANNING AND GET READY FOR YOUR STANDING OVATION! **Remember, your performance doesn’t have to take place before BBC Children in Need appeal day on 15 November - you can put on the production anytime in the school year and pay in your fundraising afterwards.** Congratulations - you’ve decided 10 STEPS TO A to raise money for BBC Children in Need and to bring a bit of the magic STAR PRODUCTION of the big screen to your school! Simply follow these 10 steps to make sure you deliver a star performance: 1 Read the story synopsis, list of characters and script as a class Discuss what you’ve read and brainstorm ideas on how to bring the production to life. -

AUDITION NOTICE Jewel Theatre Company of Santa Cruz Seeks Equity and Non-Equity Actors

AUDITION NOTICE Jewel Theatre Company of Santa Cruz seeks Equity and Non-Equity Actors Seeking actor/singers who move, of all ages, genders and ethnicities. ___________________________________________________________ A World Premiere Musical DAVID COPPERFIELD, THE NEW MUSICAL Book, Lyrics and Music by Jeffrey Scharf Co-Produced with J. Scharf Music Directed & Co-Produced by Joseph Paul Stachura Music Director Max Bennett-Parker Choreographer Lee Ann Payne Adapted from Charles Dickens’ favorite and most autobiographical novel, DAVID COPPERFIELD, THE NEW MUSICAL brings Copperfield’s story to tuneful life, from birth to marriage. As a child, David endures the sadism of his step-father Murdstone, the cruelty of the villainous schoolmaster Creakle, and the mind-numbing routine of a London sweatshop. As an adult, he is visited by happiness and success, tragedy and loss. Along the way, he meets some of Dickens’ most memorable characters: his formidable Aunt Betsey, the sea-faring Peggotty family, the monosyllabic coachman Barkis, the grandiloquent Mr. Micawber, and the contemptible Uriah Heep. AUDITION DATES: Monday, September 24, 2018, 11:00am – 9:00pm (in Santa Cruz) Tuesday, September 25, 2018, 11:00am – 9:00pm (in Berkeley) Saturday, September 29, 2018, 10:00am – 4:00pm (in Santa Cruz) AUDITION LOCATIONS: Mon 9/24 & Sat 9/29: Colligan Theater, 1010 River Street, Santa Cruz, CA 95060 Tues 9/25: Shotgun Studio B, 1201 University Ave (at Curtis), Berkeley, CA 94702 WALK-IN OR BY APPOINTMENT: If you would like to reserve a time, please email [email protected] and provide your preferred date/time. For questions or to sign up by phone, call 831-331-7942 between 10:00am and 5:00pm. -

David Copperfield As an Autobiographical Novel Ans:- It Is Proverbially Said--"It's in Vain

David Copperfield as an autobiographical novel Ans:- It is proverbially said--"It's in vain... to recall the past, unless it works some influence upon the present." Norrie Epstein, in The Friendly Dickens, notes that by writing about his parents and reliving his childhood, Dickens triumphed over his past and would never again need to make a neglected child the central focus of a novel. David Copperfield's life was a veiled image of the author's life, though the novel still maintains the potent themes that made Dickens legendary. Dickens portrayed his parents and his attitude towards them in many of the characters in David Copperfield. Dickens's parents were high-spirited, airy people who were not, in Dickens's eyes, good parents. In David Copperfield, Dickens's mother, Elizabeth Dickens, was portrayed as the lovely widow, Clara Copperfield. Clara was the naive and girlish mother of David. Behind David's back, she married Edward Murdstone, a cruel, heartless man. David felt betrayed by his mother, just as Dickens felt betrayed by his own mother. After Dickens's father was arrested because of his debts, his mother sent Charles to work at the terrible Warren's Blacking Factory, a shoe-making factory. This experience scarred and alienated Dickens for life and was a theme in many of his books. Dora Spenlow, David's first wife, was also another image of Elizabeth Dickens, Charles' mother. Like Mrs. Copperfield, Dora had a blithe personality and was beautiful, angelic but naive. She enchanted David and he instantaneously loved her. "I was a captive and a slave.