WORKHOUSE – a Talk by Rosemary Church Introduction a Brief Outline of Why Workhouses Came Into Being

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ockwell House Oxfordshire

OCKWELL HOUSE OXFORDSHIRE OCKWELL HOUSE OXFORDSHIRE A beautifully maintained and well equipped small estate with extensive outbuildings within striking distance of Oxford Faringdon 5 miles • Abingdon 12 miles • Witney 12 miles Didcot 14 miles (London Paddington approximately 42 minutes) Oxford Parkway 23 miles (London Marylebone approximately 65 minutes) • London 80 miles (Distances and times are approximate) Reception hall • Drawing room • Dining room • Study • Sitting room Kitchen/breakfast room • Utility/laundry room • Boot room Master bedroom suite with bathroom and dressing room • Guest bedroom suite • 4 further bedrooms Family bathroom Large second floor games room and extensive storage Party Barn with kitchen and guest accommodation • 2 bedroom guest cottage • Housekeepers studio flat 2 further staff flats • Garden room • Extensive range of stores and garaging Beautiful gardens and grounds Long tree-lined drive Tennis court Swimming pool Stables 40m x 20m Manége Martin Collins Clopf Fibre surface Paddocks Pond Delightful views Approximate gross internal floor area of the main house 6,401 sq ft with a further 6,633 sq ft of secondary accommodation and outbuildings In all about 28 acres For Sale Freehold Oxford Country Department 280 Banbury Road, 55 Baker Street, Summertown, Oxford OX2 7ED London W1U 8AN Tel: +44 1865 790 077 Tel: +44 20 7861 1707 [email protected] [email protected] www.knightfrank.co.uk These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the brochure. Oxfordshire Ockwell House is situated just outside the hamlet of Hatford. -

The Berkshire Echo 52

The Berkshire Echo Issue 52 l The Grand Tour: “gap” travel in the 18th century l Wartime harvest holidays l ‘A strange enchanted land’: fl ying to Paris, 1935 l New to the Archives From the Editor From the Editor It is at this time of year that my sole Holidays remain a status symbol Dates for Your Diary focus turns to my summer holidays. I in terms of destination and invest in a somewhat groundless belief accommodation. The modern Grand Heritage Open Day that time spent in a different location Tour involves long haul instead This year’s Heritage Open Day is Saturday will somehow set me up for the year of carriages, the lodging houses 11 September, and as in previous years, ahead. I am confi dent that this feeling and pensions replaced by fi ve-star the Record Offi ce will be running behind will continue to return every summer, exclusivity. Yet our holidays also remain the scenes tours between 11 a.m. and 1 and I intend to do nothing to prevent it a fascinating insight into how we choose p.m. Please ring 0118 9375132 or e-mail doing so. or chose to spend our precious leisure [email protected] to book a place. time. Whether you lie fl at out on the July and August are culturally embedded beach or make straight for cultural Broadmoor Revealed these days as the time when everyone centres says a lot about you. Senior Archivist Mark Stevens will be who can take a break, does so. But in giving a session on Victorian Broadmoor celebrating holidays inside this Echo, it So it is true for our ancestors. -

June 2013 Thanksgivings and Baptisms with Revd Eddy

STANFORD IN THE VALE WITH Sunday 7th July Trinity 6 8.30 am Holy Communion (Goosey) GOOSEY & HATFORD 9.45 am Just Come (Stanford) 10.15 am Parish Communion (Stanford) PARISH NEWSLETTER St. Denys Kids each Sunday during term time, except when Family Service, where during the main Parish Communion Service the children go to the Village Hall. Contact 718784 Open House On most Saturdays St Denys’ Church is open between 10 am and noon for coffee and tea, cake and chat. No charge. Do pop in. You’ll find a warm and friendly welcome. This is a good time to talk to discuss weddings, June 2013 thanksgivings and baptisms with Revd Eddy SERVICES FOR THE MONTH FROM THE REGISTERS nd Sunday 2 June Trinity 1 Funeral Service 8.30 am Holy Communion (Goosey) Monday 29th April 9.45 am Just Come (Stanford) Elizabeth Dunkanna Soulsby 10.15 am Parish Communion (Stanford) Huntersfield Aged 99 years th Tuesday 4 June 3.00 pm Time for God (Stanford) Marriage Service th Thursday 6 June Saturday 4th May 2.30 pm Holy Communion at the Grange Mark Pembroke and Jayne Eltham th Sunday 9 June Trinity 2 Baptism 8.30 am Holy Communion (Hatford) Sunday 19th May 9.45 am Just Come (Stanford) Bailey Matthew Rolls 10.15 am Parish Communion (Stanford) Archie Anker at All Saints, Goosey 6.00 pm Evening Prayer (Stanford) WHO’S WHO IN THE PARISH? Wednesday 12th June Priest-in-Charge 10.30 am Holy Communion (Stanford) The Revd Paul Eddy 710267 th Assistant (part-time) Curate – Sunday 16 June Trinity 3 The Revd. -

Index of Faringdon Peculiar Probate Records

INDEX OF FARINGDON PECULIAR PROBATE RECORDS Introduction This index to probate records for the Peculiar Court of Faringdon spans 1547-1853. The Peculiar Court came under the jurisdiction of the Prebend of Salisbury, and only covered the Berkshire parishes of Faringdon and Little Coxwell. The index provides basic biographical details extracted from the filed probate documents held at Berkshire Record Office, together with information about what legal documents survive for each case. The documents themselves can be consulted at the Berkshire Record Office. Abbreviations used als alias/otherwise known as inv inventory of possessions nunc nuncupative (spoken by the deceased) renunc renunciation © Berkshire Record Office. Reproduced by permission INDEX OF FARINGDON PECULIAR PROBATE RECORDS Surname Forenames Year Place Occupation Document types Reference no. (D/A3/ ) ADAMS GEORGE 1825 FARINGDON YEOMAN Will 5/31 ADAMS JANE 1756 FARINGDON WIDOW Will 2/19 ADAMS JANE 1760 FARINGDON SPINSTER Will 2/20 ADAMS JOHN 1691 FARINGDON MALTSTER Bond, inv 2/8 ADAMS MARK 1724 WESTBROOK, FARINGDON LABOURER Bond, inv, declaration 2/12 ADAMS NICHOLAS 1748 FARINGDON MALSTER Will 2/18 the elder ADDAMS MARK see ADAMS ADDIMS JOHN see ADAMS ALEXANDER JOSEPH 1683 LITTLEWORTH YEOMAN Bond, inv 2/7 ALFORD JOHN 1631 WESTBROOK, FARINGDON - Inv. 2/2 ALNUTT BENJAMIN 1697 FARINGDON YEOMAN Will, inv 2/10 AMBORSE JANE 1730 LITTLEWORTH WIDOW Will 2/16 AMBROSE NATHANIEL 1715 LITTLEWORTH GENTLEMAN Bond, inv 2/11 ANDREWES JOHN 1645 LITTLE COXWELL - Inv. 2/3 ANDREWES WILLIAM 1645 -

Notice of Election Vale Parishes

NOTICE OF ELECTION Vale of White Horse District Council Election of Parish Councillors for the parishes listed below Number of Parish Number of Parish Parishes Councillors to be Parishes Councillors to be elected elected Abingdon-on-Thames: Abbey Ward 2 Hinton Waldrist 7 Abingdon-on-Thames: Caldecott Ward 4 Kennington 14 Abingdon-on-Thames: Dunmore Ward 4 Kingston Bagpuize with Southmoor 9 Abingdon-on-Thames: Fitzharris Ock Ward 2 Kingston Lisle 5 Abingdon-on-Thames: Fitzharris Wildmoor Ward 1 Letcombe Regis 7 Abingdon-on-Thames: Northcourt Ward 2 Little Coxwell 5 Abingdon-on-Thames: Peachcroft Ward 4 Lockinge 3 Appleford-on-Thames 5 Longcot 5 Appleton with Eaton 7 Longworth 7 Ardington 3 Marcham 10 Ashbury 6 Milton: Heights Ward 4 Blewbury 9 Milton: Village Ward 3 Bourton 5 North Hinksey 14 Buckland 6 Radley 11 Buscot 5 Shrivenham 11 Charney Bassett 5 South Hinksey: Hinksey Hill Ward 3 Childrey 5 South Hinksey: Village Ward 3 Chilton 8 Sparsholt 5 Coleshill 5 St Helen Without: Dry Sandford Ward 5 Cumnor: Cumnor Hill Ward 4 St Helen Without: Shippon Ward 5 Cumnor: Cumnor Village Ward 3 Stanford-in-the-Vale 10 Cumnor: Dean Court Ward 6 Steventon 9 Cumnor: Farmoor Ward 2 Sunningwell 7 Drayton 11 Sutton Courtenay 11 East Challow 7 Uffington 6 East Hanney 8 Upton 6 East Hendred 9 Wantage: Segsbury Ward 6 Fyfield and Tubney 6 Wantage: Wantage Charlton Ward 10 Great Coxwell 5 Watchfield 8 Great Faringdon 14 West Challow 5 Grove: Grove Brook Ward 5 West Hanney 5 Grove: Grove North Ward 11 West Hendred 5 Harwell: Harwell Oxford Campus Ward 2 Wootton 12 Harwell: Harwell Ward 9 1. -

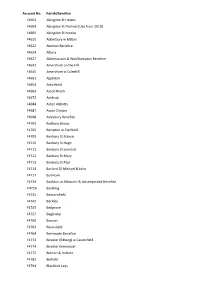

List of Fee Account

Account No. Parish/Benefice F4603 Abingdon St Helens F4604 Abingdon St Michael (Use from 2019) F4605 Abingdon St Nicolas F4610 Adderbury w Milton F4622 Akeman Benefice F4624 Albury F4627 Aldermaston & Woolhampton Benefice F4642 Amersham on the Hill F4645 Amersham w Coleshill F4651 Appleton F4654 Arborfield F4663 Ascot Heath F4672 Ashbury F4684 Aston Abbotts F4687 Aston Clinton F4698 Aylesbury Benefice F4703 Badbury Group F4705 Bampton w Clanfield F4709 Banbury St Francis F4710 Banbury St Hugh F4711 Banbury St Leonard F4712 Banbury St Mary F4713 Banbury St Paul F4714 Barford SS Michael & John F4717 Barkham F4724 Basildon w Aldworth & Ashampstead Benefice F4726 Baulking F4735 Beaconsfield F4742 Beckley F4745 Bedgrove F4757 Begbroke F4760 Benson F4763 Berinsfield F4764 Bernwode Benefice F4773 Bicester (Edburg) w Caversfield F4774 Bicester Emmanuel F4775 Bierton & Hulcott F4782 Binfield F4794 Blackbird Leys F4797 Bladon F4803 Bledlow w Saunderton & Horsenden F4809 Bletchley F4815 Bloxham Benefice F4821 Bodicote F4836 Bracknell Team Ministry F4843 Bradfield & Stanford Dingley F4845 Bray w Braywood F6479 Britwell F4866 Brize Norton F4872 Broughton F4875 Broughton w North Newington F4881 Buckingham Benefice F4885 Buckland F4888 Bucklebury F4891 Bucknell F4893 Burchetts Green Benefice F4894 Burford Benefice F4897 Burghfield F4900 Burnham F4915 Carterton F4934 Caversham Park F4931 Caversham St Andrew F4928 Caversham Thameside & Mapledurham Benefice F4936 Chalfont St Giles F4939 Chalfont St Peter F4945 Chalgrove w Berrick Salome F4947 Charlbury -

Draft Recommendations on the New Electoral Arrangements for Vale of White Horse District Council

` Draft recommendations on the new electoral arrangements for Vale of White Horse District Council Electoral review October 2012 Translations and other formats For information on obtaining this publication in another language or in a large-print or Braille version please contact the Local Government Boundary Commission for England: Tel: 020 7664 8534 Email: [email protected] The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by the Local Government Boundary Commission for England with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 100049926 2012 Contents Summary 1 1 Introduction 3 2 Analysis and draft recommendations 5 Submissions received 6 Electorate figures 6 Council size 6 Electoral fairness 7 General analysis 7 Electoral arrangements 8 North and West 8 Central and South 9 Abingdon 11 East 11 North-East 12 South-East 13 Conclusions 15 Parish electoral arrangements 15 3 What happens next? 18 4 Mapping 20 Appendices A Table A1: Draft recommendations for Vale of White 21 Horse District Council B Glossary and abbreviations 24 Summary The Local Government Boundary Commission for England is an independent body which conducts electoral reviews of local authority areas. The broad purpose of an electoral review is to decide on the appropriate electoral arrangements – the number of councillors, and the names, number and boundaries of wards or divisions – for a specific local authority. We are conducting an electoral review of Vale of White Horse District Council to provide improved levels of electoral equality across the authority. -

Andrea Thomas-Barnaby

[For OACP use only] Approval Number APP/SWC/PA/034/0411 Title Mr Mrs x Miss Ms Dr Prof Full Name First Name Andrea Family Name Thomas-Barnaby Gender Male Female x Daytime Telephone Number Mobile 07554 474559 Email [email protected] Date of last DBS check, or state never September 2013 Course type Completed ddmmyyyy 1. Catheterization and incontinence care management 2. Infection Control 3. Food Hygiene 4. Adult resuscitation 5. Medication Administration 6. Manual Handling 7. Falls Awareness 8. Equality and Diversity 9. Health and Safety 1 | P a g e 10. Fire Awareness 11. Safeguarding Adults 1 & 2 12. Safeguarding Children 1 13. Blood glucose monitoring 14. Vital signs observation 15. Conflict resolution 16. Principles of care 17. Diet and Nutrition 18. Prevention and Management of Pressure Damage and Ulcers 19. Record and Documentation 20. Dementia care and management 21. Communication Car Driver Yes x No Approximate charges: Per hour 8am – 8pm Monday to Friday £ 18 Per hour 8am – 8pm Weekends and Bank Holidays £ 20 Per hour 8pm – 8am Overnight care £ 20 Sleep-overs £ 60 Mileage £ negotiable Short description 2 | P a g e Which tasks are provided as a Personal Assistant? Personal care x Social & Leisure activities x Domestic Assistance x Work or study support Other, please state 3 | P a g e Which area the Personal Assistant works in Tick Postcode Including Broadwell, Claydon, Claydon Pike, Downington, Filkins, Fyfield, Kelmscott, Kencot, Langford, Little Faringdon, Little London, x GL7 Southrop, Thornhill, Warrens Cross x Adlestrop, -

Planning & Regulation Committee

PLANNING & REGULATION COMMITTEE MINUTES of the meeting held on Monday, 1 June 2020 commencing at 2.00 pm and finishing at 2.55 pm Present: Voting Members: Councillor Jeannette Matelot – in the Chair Councillor Stefan Gawrysiak (Deputy Chairman) Councillor Mrs Anda Fitzgerald-O'Connor Councillor Pete Handley Councillor Damian Haywood Councillor Mrs Judith Heathcoat (In place of Councillor Mike Fox-Davies) Councillor Bob Johnston Councillor G.A. Reynolds Councillor Judy Roberts Councillor Dan Sames Councillor John Sanders Councillor Alan Thompson Councillor Richard Webber Officers: Whole of meeting G. Warrington & J. Crouch (Law & Governance); R. Wileman and D. Periam (Planning & Place) Part of meeting Agenda Item Officer Attending 6 C. Kelham (Planning & Place) 8. B. Stewart-Jones (Planning & Place) The Committee considered the matters, reports and recommendations contained or referred to in the agenda for the meeting, together with a schedule of addenda circulated prior to the meeting and decided as set out below. Except as insofar as otherwise specified, the reasons for the decisions are contained in the agenda, reports and schedule, copies of which are attached to the signed Minutes. PN3 15/20 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE AND TEMPORARY APPOINTMENTS (Agenda No. 1) Apology for Absence Temporary Appointment Councillor Mike Fox-Davies Councillor Judith Heathcoat 16/20 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST - SEE GUIDANCE NOTE OPPOSITE (Agenda No. 2) Councillor Fitzgerald-O’Connor (Local Member) advised that she was the local member for Item 6 (Land to the West of Hatford Quarry – Application MW.0066/19). 17/20 MINUTES (Agenda No. 3) The minutes of the meeting held on 9 March were approved. -

Oxfordshire Minerals and Waste Local Plan: Part 2 Site Allocations

OXFORDSHIRE MINERALS AND WASTE LOCAL PLAN PART 2 – SITE ALLOCATIONS PREFERRED OPTIONS CONSULTATION (Regulation 18 Consultation) January 2020 Contents Contents Contents ..................................................................................................................... 2 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 4 Purpose of the Document ....................................................................................... 4 How to comment on the Draft Sites Plan ................................................................ 5 What happens next? ............................................................................................... 6 2. Mineral Context ...................................................................................................... 7 National Planning Policy Framework ...................................................................... 7 Planning Practice Guidance ................................................................................... 7 Oxfordshire Minerals and Waste Local Plan ........................................................... 8 Core Strategy Vision and Objectives ................................................................... 8 How much mineral does Oxfordshire need? ........................................................... 9 Ensuring flexibility and maintaining supply ............................................................. 9 Where should we allocate Mineral sites? ............................................................. -

Buyersguide Cv2011 12 Editorial Pages 07/07/2011 15:57 Page 1

buyersguide cv2011_12_Editorial Pages 07/07/2011 15:57 Page 1 BUYERS’ GUIDE 2011/12 SPORTS INSIGHT SPORTS BUYERS’ GUIDE20011/12Sportswww.sports-insight.co.uk WWW.SPORTS-INSIGHT.CO.UK PRICE £9.99 Insight MAKURASPORT.COM Reydon_Layout 1 19/07/2011 15:07 Page 1 1 - Contents_Intro page 22/07/2011 14:58 Page 3 Contents Every cloud… More takeovers will occur in the UK sports and leisurewear sector this year, if a recent industry report is to be believed. Financial analyst Plimsoll says one in five companies could change ownership as a result of too many firms chasing too little market. One of the most fragmented sectors in the UK, it appears that some businesses are facing an uncertain future. The winners will be cash rich rivals, waiting to swoop on companies put up for sale at rock bottom prices. CONTENTS A potential silver lining for the sports trade next year could be the London Olympics. One sports retailer in the capital said part of the legacy of London 2012 would be a new breed of competitors and a fresh wave of up and coming athletes for retailers to kit out and 18 Sports merchandisers 44 Sports agents support. I hope this is the case and your 25 Sports governing bodies 48 Buying groups/multiples business’ bottom line benefits as a result. 34 Trade associations 52 Suppliers A-Z listing Jeff James 36 Marketing specialists 92 Independent sports retailers 42 Association of 184 Suppliers by product Editor Professional Sales Agents category Although every care is taken to ensure that all Published by Design/Typesetting information is accurate and up to date, the publisher Maze Media (2000) Ltd, Ace Pre-Press Ltd, 19 Phoenix Court, cannot accept responsibility for mistakes or omissions. -

Oxfordshire Early Years Provider Directory the Following List Gives

Oxfordshire Early Years Provider Directory The following list gives you contact details of providers currently registered to offer the nursery education funding entitlement in your local area. Please contact these providers direct to enquire if they have places available, and for more information on session times and lengths. Private, voluntary and independent providers will also be able to tell you how they operate the entitlement, and give you more information about any additional costs over and above the basic grant entitlement of 15 hours per week. Admissions for Local Authority (LA) school and nursery places for three and four year olds are handled by the nursery or school. Nursery Education Funding Team Contact information for general queries relating to the entitlement: Telephone 01865 815765 Email [email protected] Oxfordshire Early Years Provider Directory Name Telephone Address Independent The Manor Preparatory School 01235 858458 Faringdon Road, Shippon, Abingdon, OX13 6LN Pinewood School 01793782205 Bourton, Swindon, SN6 8HZ Our Lady's Abingdon Junior 01235523147 St. Johns Road, Abingdon, OX14 2HB School Josca's Preparatory School 01865391570 Josca's House, Kingston Road, Frilford, Abingdon, OX13 5NX Ferndale Preparatory School 01367240618 5-7 Bromsgrove, Faringdon, SN7 7JF Chandlings 01865 730771 Chandlings, Bagley Wood, Kennington, Oxford, OX1 5ND Oxfordshire Early Years Provider Directory Name Telephone Address LEA Nursery, Primary or Special School Wootton St Peter Church of 01865 735643 Wootton Village,