Cades Cove During the Nineteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010 Annual Report • Preserve

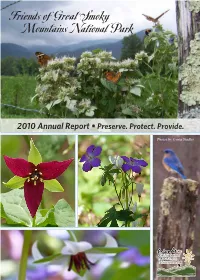

Friends of Great Smoky Mountains National Park 2010 Annual Report • Preserve. Protect. Provide. Photos by Genia Stadler About This Publication Our 2010 Annual Report exists exclusively in digital format, available on our website at www.FriendsOfTheSmokies.org. In order to further the impact of our donors’ resources for the park’s benefit we chose to publish this report online. If you would like a paper copy, you may print it from home on your computer, or you may request a copy to be mailed to you from our office (800-845-5665). We are committed to conserving natural resources in and around Great Smoky Mountains National Park! The images used on the front and back covers are If your soul can belong to provided through the generosity, time, and talent of a place, mine belongs here. Genia Stadler of Sevierville, Tennessee. Genia Stadler When asked to describe herself and her love for the Smokies, she said, “I was born in Alabama, but Tennessee always felt like home to me. My love for the Smokies started as a small child. My daddy brought me here each summer before he passed away. I was 9 when he died, and by then I had fallen in love with the Smokies. My husband (Gary) and I had the chance to build a cabin and move here in 2002, so we jumped at the chance. Since then, we’ve been exploring the park as often as we can. We’ve probably hiked over 300 miles of the park’s trails (many repeats), and I’m trying to pass my love for this place on to my two children and two grandchildren. -

Creating a Sense of Communityamong the Capital City Cherokees

CREATING A SENSE OF COMMUNITYAMONG THE CAPITAL CITY CHEROKEES by Pamela Parks Tinker A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies Committee: ____________________________________ Director ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Program Director ____________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date:________________________________ Spring 2016 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Creating a Sense Of Community Among Capital City Cherokees A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies at George Mason University By Pamela Parks Tinker Bachelor of Science Medical College of Virginia/Virginia Commonwealth University 1975 Director: Meredith H. Lair, Professor Department of History Spring Semester 2016 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia Copyright 2016 Pamela Parks Tinker All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements Thanks to the Capital City Cherokee Community for allowing me to study the formation of the community and for making time for personal interviews. I am grateful for the guidance offered by my Thesis Committee of three professors. Thesis Committee Chair, Professor Maria Dakake, also served as my advisor over a period of years in planning a course of study that truly has been interdisciplinary. It has been a joyful situation to be admitted to a variety of history, religion and spirituality, folklore, ethnographic writing, and research courses under the umbrella of one Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies program. Much of the inspiration for this thesis occurred at George Mason University in Professor Debra Lattanzi Shutika’s Folklore class on “Sense of Place” in which the world of Ethnography opened up for me. -

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory Carter Shields Homestead Great Smoky Mountains NP

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 1998 Carter Shields Homestead Great Smoky Mountains NP - Cades Cove Subdistrict Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Carter Shields Homestead Great Smoky Mountains NP - Cades Cove Subdistrict Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI), a comprehensive inventory of all cultural landscapes in the national park system, is one of the most ambitious initiatives of the National Park Service (NPS) Park Cultural Landscapes Program. The CLI is an evaluated inventory of all landscapes having historical significance that are listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, or are otherwise managed as cultural resources through a public planning process and in which the NPS has or plans to acquire any legal interest. The CLI identifies and documents each landscape’s location, size, physical development, condition, landscape characteristics, character-defining features, as well as other valuable information useful to park management. Cultural landscapes become approved CLIs when concurrence with the findings is obtained from the park superintendent and all required data fields -

The Etiquette and Protocol of Visiting Cades Cove Cemeteries

APPENDIX: THE ETIQUEttE AND PROTOCOL OF VISITING CADES COVE CEMETERIES A book about the cemeteries of Cades Cove is an invitation to visit those cemeteries in a way that gives them a visibility and a recognition they may not have previously had. Those driving Loop Road in the cove are invited to pull into one of the churches, enter its sanctuary, and walk the grounds around its graveyard. This underscores our responsibility to reiterate National Park Service (NPS) regulations for cemetery visi- tors within the park. They are simple. Visit the cemeteries with the rev- erence, dignity, and respect you would exercise visiting the burial places of relatives and friends. You are visiting burial places of those who have family and relatives somewhere, many in communities nearby, and on any given day, as we found doing our research, family descendants come to pay their respects. Cemeteries have the protocol and a self-imposed “shushing” effect on visitors. They are stereotypically characterized as “feminine” in their qualities, but the intent is understood. Cemeteries are quiet, peaceful, serene, calming, nurturing (spiritually and emotionally), a manifestation of Mother Earth, the womb to which we all return (Warner 1959); in their stillness, they seem 10 degrees cooler. While in the feld, we wit- nessed the demurring effects of cemeteries on visitors. We heard car © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), 153 under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 G. S. Foster and W. E. Lovekamp, Cemeteries and the Life of a Smoky Mountain Community, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23295-5 154 APPENDIX: THE ETIQUETTE AND PROTOCOL OF VISITING CADES … doors closing and visitors talking as they approached, but by the time they arrived at the cemetery, they were whispering in muffed tones. -

Marc Woodmansee's Letter to Horace Kephart

MARC WOODMANSEE’S LETTER TO HORACE KEPHART January 26, 1919 Figure 1. Horace Kephart with snake Melissa Habit ENGL 618 Dr. Gastle 7 December 2015 INTRODUCTION This edition is created from the manuscript of Marc Woodmansee’s letter to Horace Kephart on January 26, 1919. Within this letter, Marc Woodmansee discusses a few of Kephart’s articles that he was reading at the time. In addition, he informs Kephart of Harry B. Harmer’s weapon collection, which includes various Colt Company rifles and other revolvers. He also encourages him to come and visit as well as to get in touch with Harmer if he goes north. Other letters from Woodmansee to Kephart continue to discuss weapon collections, prices of various weapons, and the magazines, All Outdoors and Our Southern Highlands (while still a periodical, The Southern Highlands, in Outing magazine). Woodmansee and Kephart have a professional friendship due to their mutual interest in weaponry. Through observation of other letters, it is apparent that Woodmansee and Kephart’s relationship is more personal than this letter leads on. Woodmansee discusses his romantic life, personal interests, and Kephart’s children. Marc Woodmansee was born on Dec 11, 1873 in Lee, Iowa. At the time of his letter to Horace Kephart, he was working for the Standard Oil Office as a manager in Des Moines, Iowa and was living with his mother, Mary Woodmansee. According to “Out-of-Doors,” Woodmansee is one of the top collectors of Kentucky rifles in the nation; in 1919, his collection totaled over fifty rifles. The letter’s recipient, Horace Kephart, was born in 1862 in Pennsylvania, although he grew up in Iowa where he was an avid adventurer. -

Kindergarten the World Around Us

Kindergarten The World Around Us Course Description: Kindergarten students will build upon experiences in their families, schools, and communities as an introduction to social studies. Students will explore different traditions, customs, and cultures within their families, schools, and communities. They will identify basic needs and describe the ways families produce, consume, and exchange goods and services in their communities. Students will also demonstrate an understanding of the concept of location by using terms that communicate relative location. They will also be able to show where locations are on a globe. Students will describe events in the past and in the present and begin to recognize that things change over time. They will understand that history describes events and people of other times and places. Students will be able to identify important holidays, symbols, and individuals associated with Tennessee and the United States and why they are significant. The classroom will serve as a model of society where decisions are made with a sense of individual responsibility and respect for the rules by which they live. Students will build upon this understanding by reading stories that describe courage, respect, and responsible behavior. Culture K.1 DHVFULEHIDPLOLDUSHRSOHSODFHVWKLQJVDQGHYHQWVZLWKFODULI\LQJGHWDLODERXWDVWXGHQW¶V home, school, and community. K.2 Summarize people and places referenced in picture books, stories, and real-life situations with supporting detail. K.3 Compare family traditions and customs among different cultures. K.4 Use diagrams to show similarities and differences in food, clothes, homes, games, and families in different cultures. Economics K.5 Distinguish between wants and needs. K.6 Identify and explain how the basic human needs of food, clothing, shelter and transportation are met. -

Horace Kephart Bookstores and Other Commercial Booksellers

Not so random thoughts and selective musings of a mountaineer on the recently released biography Back of Back of Beyond by George Ellison and Janet McCue is available through the Great Smoky Beyond and works of Mountains Association web site, at GSMA Horace Kephart bookstores and other commercial booksellers. Our Southern Highlanders and By Don Casada, amateur historian Camping and Woodcraft, both by Horace © June, 2019 Kephart, are also available through those Friends of the Bryson City Cemetery venues. Early editions of Our Southern Highlanders and Camping and Woodcraft are available free on line. Note: a Timeline of the life of Horace Kephart is available on the FBCC website 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1833 map – Robert Brazier, with old roads highlighted, modern locations marked Maggie Valley Cherokee Fontana Village Bryson City 10 11 These are my mountains 12 13 My valleys 14 15 These are my rivers 16 Flowing like a song 17 These are my people Bland Wiggins and Jack Coburn Jim and Bertha Holden home, Middle Peachtree Christine & Elizabeth Cole Joseph and Cynthia Hoyle Cole home Brewer Branch Granville Calhoun at Bone Valley home Sources: Bryan Jackson, TVA collection – Atlanta National Archives, Open Parks Network 18 My memories Hall Casada, Tom Woodard, Commodore Casada on a camping trip with a “Mr. Osborne of India” – circa 1925, absent the sanctioned camping gear from Camping and Woodcraft. 19 These are my mountains 20 This is my home Photo courtesy of Bo Curtis, taken in late 1950s by his father, Keith 21 These are not just my mountains and my valleys; These are my people and their memories. -

The Tennessee Militia System, 1772-1857

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2003 Pioneers, patriots, and politicians : the Tennessee militia system, 1772-1857 Trevor Augustine Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Smith, Trevor Augustine, "Pioneers, patriots, and politicians : the Tennessee militia system, 1772-1857. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2003. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5189 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Trevor Augustine Smith entitled "Pioneers, patriots, and politicians : the Tennessee militia system, 1772-1857." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. Stephen Ash, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Trevor Augustine Smith entitled "Pioneers, Patriots, and Politicians: The Tennessee Militia System, 1772-1857." I have examined the finalpaper copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements forthe degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. -

Great Smoky Mountains National Park Roads & Bridges, Haer No

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ROADS & BRIDGES, HAER NO. TN-35-D CADES COVE AND LAUREL CREEK ROADS Between Townsend Wye and Cades Cove LtAtM» Gatlinburg Vicinity rtnElC Sevier County TEA/A/ .Tennessee _-^v WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA PHOTOGRAPHS MEASURED AND INTERPRETIVE DRAWINGS HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD National Park Service Department of the Interior P.O. Box 37127 Washington, D.C. 20013-7127 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD # lib- ' GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ROADS AND BRIDGES, CADES COVE AND LAUREL CREEK ROADS HAER NO. TN-35-D Location: Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee, between Cades Cove and the Townsend Wye Date of Construction ca. 1825 (improvement construction by NPS in 1930s-50s) Type of Structure Roads, Bridges, Tunnels and Landscapes Use: National Park Transportation System Engineer: U.S. Bureau of Public Roads and National Park Service Fabricator/Builder Various private and public contractors r^ Owner: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Great Smoky Mountains National Park Significance: The transportation system of Great Smoky Mountains National Park is representative of NPS park road design and landscape planning throughout the country. Much of the construction work was undertaken by the Civilian Conservation Corps during the 1930s. Proj ect Information: Documentation was conducted during the summer of 1996 under the co-sponsorship of HABS/HAER, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the National Park Service Roads and Parkway Program and funded through the Federal Lands Highway Program. Measured drawings were produced by Edward Lupyak, field supervisor, Matthew Regnier, Karen r\ Young, and Dorota Sikora (ICOMOS intern, Poland). The historical reports were ®B£ATGSMOKT WQUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ROADS AND BRIDGES, CADES COVE AND LAUREL CREEK ROADS HAER No TN-35-D (Page 2) prepared by Cornelius Maher and Michael • Kelleher. -

Effects of a Small-Scale Clear-Cut on Terrestrial Vertebrate Populations in the Maryville College Woods

EFFECTS OF A SMALL-SCALE CLEARCUT ON TERRESTRIAL VERTEBRATE POPULATIONS IN THE MARYVILLE COLLEGE WOODS, MARYVILLE, TN A Report of a Senior Study by Adam Lee Patterson Major: Biology Maryville College Fall, 2011 Date Approved ________________________________, by _________________________________ Faculty Supervisor Date Approved ________________________________, by _________________________________ Editor ii Abstract Ecosystems naturally change over time along with the abundance and diversity of species living within them. Disturbances of ecosystems can be natural large-scale, natural small-scale, anthropogenic large-scale, and anthropogenic small- scale. While natural disturbances and large-scale anthropogenic disturbances have been studied extensively, there is a paucity of research on the effects of small-scale anthropogenic disturbances. The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of a small-scale clearcut on terrestrial vertebrate populations. Amphibian, reptile, bird, and mammal surveys were conducted before and after clearcut of a 0.5 acre plot, and a reference plot was also surveyed. Shannon’s diversity index showed that overall species richness and diversity significantly decreased in the experimental plot. Amphibians and reptiles were found to be close to non-existent on the study plots. Bird and mammal species most affected were those that were already rare in the plot to begin with or those that are dependent on the habitat that was lost. Therefore, this senior study is an excellent baseline data set to conduct future -

Great Smoky Mountain National Park Geologic Resources Inventory

Geologic Resources Inventory Workshop Summary Great Smoky Mountain National Park May 8-9, 2000 National Park Service Geologic Resources Division and Natural Resources Information Division Version: Draft of July 24, 2000 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY An inventory workshop was held for Great Smoky Mountain National Park (GRSM) on May 8-9, 2000 to view and discuss the park’s geologic resources, to address the status of geologic mapping by the United States Geological Survey (USGS), various academics, the North Carolina Geological Survey (NCGS), and the Tennessee Geological Survey (TNGS) for compiling both paper and digital maps, and to assess resource management issues and needs. Cooperators from the NPS Geologic Resources Division (GRD), Natural Resources Information Division (NRID), NPS Great Smoky Mountain NP, USGS, NCGS, TNGS, University of Tennessee at Knoxville (UTK) and the Tennessee Department of Transportation (TDOT) were present for the two-day workshop. (See Appendix A, Great Smoky Mountain NP Geological Resources Inventory Workshop Participants, May 8-9, 2000) Day one involved a field trip throughout Great Smoky Mountain NP led by USGS Geologist Scott Southworth. Day two involved a daylong scoping session to present overviews of the NPS Inventory and Monitoring (I&M) program, the Geologic Resources Division, and the on going Geologic Resources Inventory (GRI) for North Carolina. Round table discussions involving geologic issues for Great Smoky Mountain NP included interpretation, paleontologic resources, the status of cooperative geologic mapping efforts, sources of available data, geologic hazards, and action items generated from this meeting. Brief summaries follow. Page 1 of 15 Great Smoky Mountain NP GRI Workshop Summary: May 8-9, 2000 (cont'd) OVERVIEW OF GEOLOGIC RESOURCES INVENTORY After introductions by the participants, Tim Connors and Joe Gregson presented overviews of the Geologic Resources Division, the NPS I&M Program, the status of the natural resource inventories, and the GRI in particular (see Appendix B, Overview of Geologic Resources Inventory). -

Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Historic Resource Study Great Smoky Mountains National Park

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Service National Park Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Historic Resource Study Resource Historic Park National Mountains Smoky Great Historic Resource Study | Volume 1 April 2016 VOL Historic Resource Study | Volume 1 1 As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering sound use of our land and water resources; protecting our fish, wildlife, and biological diversity; preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historic places; and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to ensure that their development is in the best interests of all our people by encouraging stewardship and citizen participation in their care. The department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island territories under U.S. administration. GRSM 133/134404/A April 2016 GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 FRONT MATTER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..........................................................................................................