Defence Committee Oral Evidence: Defending Global Britain in a Competitive Age, HC 1333

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate and Ecological Emergency Bill Great Green

Welcome to another packed edition! Thank you to everyone who has contributed. Please get in touch if you have any comments about the newsletter or anything you would like to be included for next month. Climate and Ecological Emergency Bill Many thanks to Kris Welch from the CEE Bill Alliance for an informative talk at this month’s Green Drinks on the 21st March. This was followed on Friday 26th March, the day when the bill should have had its second reading in parliament, with a nationwide day of action which saw many local people being photographed with a banner outside the Conservative Party office on Broad Street in Ludlow, calling on Ludlow MP Philip Dunne to support it in parliament. The bill now has the support of over 100 MPs. If you missed the day of action, you can still write to Philip Dunne to ask him to support the bill. More information at https://www.ceebill.uk/writetoyourmp Great Green Festival news! It has been decided that this year’s Ludlow Green Festival will go ahead on Sunday 11th July (subject to the restrictions in place at the time.) The theme will be ‘Build Back Greener’. Get the date in your diaries! More details coming soon. Don’t forget your edibles! The Incredible Edible Ludlow no- contact seed and plant swap is ongoing – find out more here: https://bit.ly/ludlowseedswap Get in touch with Ludlow 21: web: www.ludlow21.org.uk email: [email protected] facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ludlow21 Bird of the Month For the whole of recorded time the Teme has followed a route from the hills of mid-Wales to the Severn, probably quite similar to today. -

Council of Governors 27 June 2017 Chief Executive's Report

F Council of Governors 27 June 2017 Chief Executive’s Report 1. South Yorkshire and Bassetlaw Sustainability and Transformation Plan (SY&B STP) Accountable Care System and Sheffield Accountable Care Partnership. A presentation on the SY&B STP and Accountable Care developments will be given at the meeting. 2. General Election Update. Following the General Election on the 8 June 2017 it has been confirmed that Jeremy Hunt remains in post as Health Secretary. Thurrock MP Jackie Doyle-Price and Winchester MP Steve Brine will serve as junior ministers under Jeremy Hunt. Ludlow MP Philip Dunne was reappointed as minister of state for health. Lord O’Shaughnessy also remains as a junior health minister. 3. Integrated Performance Report The Integrated Performance Report for the period to April 2017 can be found on the Trust website at http://www.sth.nhs.uk/clientfiles/File/Enclosure%20B2%20- %20IPR%20for%20June%20Board%20-%20FV_pdf.pdf. During the meeting Executive Directors will highlight key points from the report. 4. Workforce Race Equality Scheme A case study featuring the work the Trust has been undertaking with staff on the Workforce Race Equality standards (WRES) was published and launched at the NHS Confederation this month. The document can be found on the Trust website www.sth.nhs.uk/news. 5. Awards and Events A summary of the awards and events reported to the Public Board of Directors from April – June 2017 is included below: April 2017 A number of STH teams are representing the Trust at the Health Service Journal’s Patient Safety Awards and Value in Healthcare Awards. -

Growing the Contribution of Defence to UK Prosperity / Foreword by Philip Dunne MP Growing the Contribution of Defence to UK Prosperity

Growing the Contribution of Defence to UK Prosperity / Foreword by Philip Dunne MP Growing the Contribution of Defence to UK Prosperity A report for the Secretary of State for Defence Philip Dunne MP July 2018 A Front cover: Flexible Manufacturing Systems at the BAE Systems F-35 machining facility at Samlesbury, Lancashire. The systems help machine complex titanium and aluminium components with unparalleled precision. Copyright BAE Systems plc. All images are Crown Copyright unless otherwise stated. Growing the Contribution of Defence to UK Prosperity / Contents Contents Foreword by Philip Dunne MP 2 Executive Summary 4 Chapter 1 National life 6 Chapter 2 Economic growth 16 Chapter 3 People 26 Chapter 4 Ideas and innovation 36 Chapter 5 Place 48 Chapter 6 Cross-cutting findings and recommendations 52 Annex A Comprehensive list of recommendations 56 Annex B Regional Maps 60 Annex C Terms of reference 86 Annex D Engagements 88 1 Foreword by Philip Dunne MP 2 Growing the Contribution of Defence to UK Prosperity / Foreword by Philip Dunne MP I am pleased to have been In addition, we have a unique opportunity as a result of asked by the Secretary of State the historic decision by the British people to leave the for Defence to undertake this European Union from March 2019, to reconsider what Review of the contribution of impacts this may have for the role of Defence in the UK Defence to the prosperity of economy. the United Kingdom. I have been asked in the Terms of Reference for the As part of the Defence and Dunne Review, set out in Annex C, to undertake this work Security Review 2015, when within an initial tight two-month timeframe, to inform I was Minister of State for Defence Procurement, the the Modernising Defence Programme work this summer. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Church Stretton Branch Is Closing on Friday 7 September 2018

1 | 1 This branch is closing – but we’re still here to help Our Church Stretton branch is closing on Friday 7 September 2018. Branch closure feedback, and alternative ways to bank 2 | 3 Sharing branch closure feedback We’re now nearing the closure of the Church Stretton branch of Barclays. Our first booklet explained why the branch is closing, and gave information on other banking services that we hope will be convenient for you. We do understand that the decision to close a branch affects different communities in different ways, so we’ve spoken to people in your community to listen to their concerns. We wanted to find out how your community, and particular groups within it, could be affected when the branch closes, and what we could do to help people through the transition from using the branch with alternative ways to carry out their banking requirements. There are still many ways to do your banking, including in person at another nearby branch, at your local Post Office or over the phone on 0345 7 345 3452. You can also go online to barclays.co.uk/waystobank to learn about your other options. Read more about this on page 6. If you still have any questions or concerns about these changes, now or in the future, then please feel free to get in touch with us by: Speaking to us in any of our nearby branches Contacting Ramona Enfield, your Community Banking Director for North Wales & Shropshire. Email: [email protected] We contacted the following groups: We asked each of the groups 3 questions – here’s what they said: MP: Philip Dunne In your opinion, what’s the biggest effect that this branch closing will have on your local Local Council: community? Councillors Lee Chapman and David Evans, Church Stretton Council You said to us: Mayor Michael Braid There were some concerns that the branch closure may have an impact on the way Customers: customers can bank – particularly small A number of customers who regularly use the businesses who rely on the branch to deposit branch cash. -

Has Your MP Pledged to ACT On

January 2011 Issue 6 Providing information, support and access to established, new or innovative treatments for Atrial Fibrillation Nigel Mills MP Eric Illsley MP John Baron MP David Evennett MP Nick Smith MP Dennis Skinner MP Julie Hilling MP David Tredinnick MP Amber Valley Barnsley Central Basildon and BillericayHHasBexleyheath and CrayfordaBlaenau sGwent Bolsover Bolton West Bosworth Madeleine Moon MP Simon Kirby MP Jonathan Evans MP Alun Michael MP Tom Brake MP Mark Hunter MP Toby Perkins MP Martin Vickers MP Bridgend Brighton, Kemptown Cardiff North Cardiff South and Penarth Carshalton and Wallington Cheadle Chesterfield Cleethorpes Henry Smith MP Edward Timpson MP Grahame Morris MP Stephen Lloyd MP Jo Swinson MP Damian Hinds MP Andy Love MP Andrew Miller MP Crawley Creweyyour and Nantwich oEasington uEastbournerEast Dunbartonshire MMPEast Hampshire PEdmonton Ellesmere Port and Neston Nick de Bois MP David Burrowes MP Mark Durkan MP Willie Bain MP Richard Graham MP Andrew Jones MP Bob Blackman MP Jim Dobbin MP Enfield North Enfield Southgate Foyle Glasgow North East Gloucester Harrogate and Knaresborough Harrow East Heywood and Middleton Andrew Bingham MP Angela Watkinson MP Andrew Turner MP Jeremy Wright MP Joan Ruddock MP Philip Dunne MP Yvonne Fovargue MP John Whittingdale MP High Peak Hornchurchppledged and Upminster lIsle of eWight Kenilworthd and Southam Lewishamg Deptford eLudlow dMakerfield Maldon Annette Brooke MP Glyn Davies MP Andrew Bridgen MP Chloe Smith MP Gordon Banks MP Alistair Carmichael MP Douglas Alexander MP -

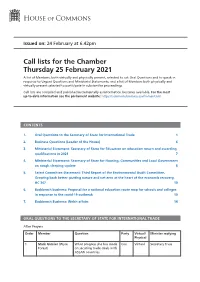

View Call Lists: Chamber PDF File 0.07 MB

Issued on: 24 February at 6.42pm Call lists for the Chamber Thursday 25 February 2021 A list of Members, both virtually and physically present, selected to ask Oral Questions and to speak in response to Urgent Questions and Ministerial Statements; and a list of Members both physically and virtually present selected to participate in substantive proceedings. Call lists are compiled and published incrementally as information becomes available. For the most up-to-date information see the parliament website: https://commonsbusiness.parliament.uk/ CONTENTS 1. Oral Questions to the Secretary of State for International Trade 1 2. Business Questions (Leader of the House) 6 3. Ministerial Statement: Secretary of State for Education on education return and awarding qualifications in 2021 7 4. Ministerial Statement: Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government on rough sleeping update 8 5. Select Committee Statement: Third Report of the Environmental Audit Committee, Growing back better: putting nature and net zero at the heart of the economic recovery, HC 347 10 6. Backbench business: Proposal for a national education route map for schools and colleges in response to the covid-19 outbreak 10 7. Backbench Business: Welsh affairs 14 ORAL QUESTIONS TO THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE After Prayers Order Member Question Party Virtual/ Minister replying Physical 1 Mark Garnier (Wyre What progress she has made Con Virtual Secretary Truss Forest) on securing trade deals with ASEAN countries. 2 Thursday 25 February 2021 Order Member Question Party Virtual/ Minister replying Physical 2, 3 Emily Thornberry Supplementary Lab Physical Secretary Truss (Islington South and Finsbury) 4 Angus Brendan Supplementary SNP Virtual Secretary Truss MacNeil (Na h-Eile- anan an Iar) 5 + 6 + Emma Hardy What recent discussions Lab Virtual Minister Hands 7 + 8 (Kingston upon Hull she has had with UK trade + 9 West and Hessle) partners on inserting clauses on human rights in future trade deals. -

Daily Report Monday, 13 June 2016 CONTENTS

Daily Report Monday, 13 June 2016 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 13 June 2016 and the information is correct at the time of publication (07:07 P.M., 13 June 2016). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 7 TREASURY 14 BUSINESS, INNOVATION AND Credit: Disclosure of SKILLS 7 Information 14 Building Regulations: Water 7 Digital Technology 14 Construction: Industry 7 EU Budget 14 Cuba: Overseas Trade 7 Lloyds Banking Group: Department for Business, Government Shareholding 15 Innovation and Skills: Mark Samworth 15 Reorganisation 8 Money Laundering 15 Industrial Health and Safety: Occupational Pensions 16 Research 9 Older People: Payments 17 Mark Samworth 10 Pension Funds 17 Post Office: Redundancy Pay 10 Pensions 17 Retail Trade: Chambers of Commerce 10 Personal Savings 18 Sunderland University: Overseas Revenue and Customs: Leaflets 18 Students 11 Secured Loans 18 Transatlantic Trade and Soft Drinks: Taxation 19 Investment Partnership 11 Tax Collection: EU Law 19 Unemployment: Young People 12 Taxation 19 CABINET OFFICE 12 Treasury: Scotland 20 Alcoholic Drinks: Crime 12 COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL Anti-corruption Innovation Hub 12 GOVERNMENT 20 Cabinet Office: Publications 13 Affordable Housing 20 Civil Servants: Recruitment 13 Communities and Local UK Membership of EU: Government: Coventry 21 Referendums 13 2 Monday, 13 June 2016 Daily Report Communities and Local Brompton -

The Common Organisation of the Markets in Agricultural Products (Transitional Arrangements) (Amendment) Regulations 2021 Which the Committee Would Be Considering

House of Commons European Statutory Instruments Committee First Report of Session 2021–22 Documents considered by the Committee on 25 May 2021 Report, together with formal minutes Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 25 May 2021 HC 60 Published on 27 May 2021 by authority of the House of Commons European Statutory Instruments Committee The European Statutory Instruments Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine and report on: (a) any of the following documents laid before the House of Commons in accordance with paragraph 3(3)(b) or 17(3)(b) of Schedule 7 to the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018— (i) a draft of an instrument; and (ii) a memorandum setting out both a statement made by a Minister of the Crown to the effect that in the Minister’s opinion the instrument should be subject to annulment in pursuance of a resolution of either House of Parliament (the negative procedure) and the reasons for that opinion, and (aa) any of the following documents laid before the House of Commons in accordance with paragraph 8(3)(b) of Schedule 5 to the European Union (Future Relationship) Act 2020— (i) a draft of an instrument; and (ii) a memorandum setting out both a statement made by a Minister of the Crown to the effect that in the Minister’s opinion the instrument should be subject to annulment in pursuance of a resolution of either House of Parliament (the negative procedure) and the reasons for that opinion, and (b) any matter arising from its consideration of such documents. -

Liaison Committee Oral Evidence from the Prime Minister, HC 1144

Liaison Committee Oral evidence from the Prime Minister, HC 1144 Wednesday 13 January 2021 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 13 January 2021. Watch the meeting Members present: Sir Bernard Jenkin (Chair); Hilary Benn; Mr Clive Betts; Sir William Cash; Yvette Cooper; Philip Dunne; Robert Halfon; Meg Hillier; Simon Hoare; Jeremy Hunt; Darren Jones; Catherine McKinnell; Caroline Nokes; Stephen Timms; Tom Tugendhat; Pete Wishart. Questions 1-103 Witness I: Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP, Prime Minister. Examination of witness Witness: Boris Johnson MP. Q1 Chair: I welcome everyone to this session of the Liaison Committee and thank the Prime Minister for joining us today. Prime Minister, we are doing our best to set a good example of compliance with the covid rules. Apart from you and me, everyone else is working from their own premises. This session is the December session that was held over until now, for your convenience, Prime Minister. I hope you can confirm that there will still be three 2021 sessions? The Prime Minister: I can indeed confirm that, Sir Bernard, and I look forward very much to further such sessions this year. Chair: The second part of today’s session will concentrate on the UK post Brexit, but we start with the Government’s response to covid. Jeremy Hunt. Q2 Jeremy Hunt: Prime Minister, thank you for joining us at such a very busy time. It is obviously horrific right now on the NHS frontline. I wondered if we could just start by you updating us on what the situation is now in our hospitals. -

Government and Opposition Reshuffle

18 January 2018 Government and opposition reshuffle At the start of January, Theresa May undertook a ministerial reshuffle, stating that the reshuffle brings “fresh talent into government” and ensures it “looks more like the country it serves.” The changes saw the promotion of sixteen women and an additional three ministers with responsibilities for housing, health and Brexit. Jeremy Hunt remains in post, overseeing the newly renamed Department of Health and Social Care. Stephen Barclay and Caroline Dinenage have replaced Philip Dunne as ministers of state, following his resignation. Labour leader, Jeremy Corbyn, announced 13 appointments to his frontbench, including Paula Sherriff, who becomes shadow minister of state for social care and mental health. This briefing includes: 1. A summary of the changes to government ministers 2. Ministerial responsibilities in the department of health and social care 3. An overview of changes to the shadow ministerial team 4. Changes made last year to the Liberal Democrat frontbench team 1. Changes to government ministers The reshuffle follows a series of cabinet resignations, the most recent being that of the first secretary of state and minister for the cabinet office, Damien Green. Green, the prime minister’s effective deputy, was a key ally of Theresa May and chaired 8 cabinet committees and taskforces. He departed the government after an investigation found he had breached the ministerial code. The secretaries for the “great offices of state” of the Treasury, Home Office and Foreign Office remain in place, and there were only minor changes to the cabinet. David Lidington, formerly the justice secretary, replaced Damian Green as minister for the cabinet office but not as first secretary of state, although it is likely he will deputise for May at PMQs. -

List of Ministers' Interests

LIST OF MINISTERS’ INTERESTS CABINET OFFICE DECEMBER 2015 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Prime Minister 3 Attorney General’s Office 5 Department for Business, Innovation and Skills 6 Cabinet Office 8 Department for Communities and Local Government 10 Department for Culture, Media and Sport 12 Ministry of Defence 14 Department for Education 16 Department of Energy and Climate Change 18 Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs 19 Foreign and Commonwealth Office 20 Department of Health 22 Home Office 24 Department for International Development 26 Ministry of Justice 27 Northern Ireland Office 30 Office of the Advocate General for Scotland 31 Office of the Leader of the House of Commons 32 Office of the Leader of the House of Lords 33 Scotland Office 34 Department for Transport 35 HM Treasury 37 Wales Office 39 Department for Work and Pensions 40 Government Whips – Commons 42 Government Whips – Lords 46 INTRODUCTION Ministerial Code Under the terms of the Ministerial Code, Ministers must ensure that no conflict arises, or could reasonably be perceived to arise, between their Ministerial position and their private interests, financial or otherwise. On appointment to each new office, Ministers must provide their Permanent Secretary with a list in writing of all relevant interests known to them which might be thought to give rise to a conflict. Individual declarations, and a note of any action taken in respect of individual interests, are then passed to the Cabinet Office Propriety and Ethics team and the Independent Adviser on Ministers’ Interests to confirm they are content with the action taken or to provide further advice as appropriate.