Sectarian Discourse in Pakistan: Case Study of District Jhang (1979-2009)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

Class, Caste, Or Race: Veils Over Social Oppression Haris Gazdar

Class, Caste, or Race: Veils Over Social Oppression Haris Gazdar When asked recently to think about “social marginalization” in Pakistan, and to carry out fieldwork on the issue in rural and urban areas of the country, an experienced team of researchers knew they were up against some usual sources of resistance. It is easy enough to think, speak and write about “economic” poverty in Pakistan—the government’s point-men notwithstanding. Societal causes of deprivation and marginalization such as caste, religion and ethnicity find few takers and many detractors. But as our intrepid researchers got about their work new demons that proved to be familiar, and yet quite unnerving, reared their heads. I have enjoyed the privilege, over the last many years, of working with a gifted group of field researchers who relish the opportunity of challenging their own imaginations and asking difficult questions.1 We have worked together on a number of social policy issues including rural poverty, urban governance, school performance, bonded labour, and migration. Our last assignment took us on a whirlwind tour along the length of the country—from Khyber to Karachi as Pakistanis are fond of alliterating—and across its breadth from Badin to Gwadar. 1 Azmat Ali Budhani and Hussain Bux Mallah are co-veterans of many such campaigns. Haris Gazdar, Class, Caste, or Race: Veils Over Social Oppression 1 Part of the brief was to understand and document diverse processes of social marginalization—or the systematic marginalization of individuals, families, and groups due to their “social” attributes such as caste, traditional occupation, kinship, ethnicity, religion and lifestyles. -

World Bank Document

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT (EA) AND THE ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK Public Disclosure Authorized PUNJAB EDUCATION SECTOR REFORMS PROGRAM-II (PESRP-II) Public Disclosure Authorized PROGRAM DIRECTOR PUNJAB EDUCATION SECTOR REFORMS PROGRAM (PESRP) SCHOOL EDUCATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB Tel: +92 42 923 2289~95 Fax: +92 42 923 2290 url: http://pesrp.punjab.gov.pk email: [email protected] Public Disclosure Authorized Revised and Updated for PERSP-II February 2012 Public Disclosure Authorized DISCLAIMER This environmental and social assessment report of the activities of the Punjab Education Sector Reforms Program of the Government of the Punjab, which were considered to impact the environment, has been prepared in compliance to the Environmental laws of Pakistan and in conformity to the Operational Policy Guidelines of the World Bank. The report is Program specific and of limited liability and applicability only to the extent of the physical activities under the PESRP. All rights are reserved with the study proponent (the Program Director, PMIU, PESRP) and the environmental consultant (Environs, Lahore). No part of this report can be reproduced, copied, published, transcribed in any manner, or cited in a context different from the purpose for which it has been prepared, except with prior permission of the Program Director, PESRP. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This document presents the environmental and social assessment report of the various activities under the Second Punjab Education Sector Reforms Program (PESRP-II) – an initiative of Government of the Punjab for continuing holistic reforms in the education sector aimed at improving the overall condition of education and the sector’s service delivery. -

An Essay on the History of Land and Reform in Pakistan

The Fourth Round, And Why They Fight On: An Essay on the History of Land and Reform in Pakistan Haris Gazdar ([email protected]) March 2009 This paper was written for PANOS South Asia in response to a request for a speculation essay on contemporary issues in land reform in Pakistan seen from a historical perspective. The author is grateful to Ghazah Abbasi and Hussain Bux Mallah for assistance, and to Sobia Ahmed, Ali Cheema and Sohaib Naeem for comments on an earlier draft. Collective for Social Science Research 173-I, Block 2, PECHS, Karachi 75400, Pakistan Phone: +9221-455-1482, Fax: +9221-454-7532 researchcollective.org Glossary Word Translation batai crop product sharing between landowner and peasant benami alienation of land to anonymous persons bhaichara village where all claimants of landholdings were perceived to be the joint village holders of the village deh smallest administrative division of land (in Sindh) for land revenue purposes doabs territory between two rivers goth village in Sindh haari sharecropper in Sindh jaanglee jungle dwellers jagirdari possession of 'jagir' jagirs land awarded by colonial officers on which revenue was not due kammis pejorative term used for menial workers katchi abadi irregular settlement khasra girdavri village revenue record laapo share of crop belonging to 'zamindar', equivalent to 1/16th of total crop produce honorary government-appointed person for revenue collection and control of lambardar village affairs smallest administrative division of land (in Punjab and NWFP) for land revenue mahal purposes; village land revenue system in Punjab and NWFP, based on recognizing the village as mahalwari the basic unit of land administration masihi generic term used for Christians Mazhabi Sikh “low-caste” Sikh convert mukhtiarkar town level land revenue government official in Sindh landowner in villages in Punjab, appointed by the revenue department as its nambardar honorary representative; responsible for collecting land revenue. -

Jhang: Annual Development Program and Its Implementation (2008-09)

April 2009 CPDI District Jhang: Annual Development Program and its Implementation (2008-09) Table of Contents 1. Background 2. Annual Development Program (2008-09) 3. Implementation of Annual Development Program (2008-09): Issues and Concerns 4. Recommendations Centre for Peace and Development Initiatives (CPDI) 1 District Jhang: Annual Development Program and its Implementation (2008-09) 1. Background Jhang district is located in the Punjab province. Total area of the district is 8,809 square kilometers. It is bounded on the north by Sargodha and Hafizabad districts, on the south by Khanewal district, on the west by Layyah, Bhakkar and Khushab districts, on the east by Faisalabad and Toba Tek Singh districts and on the south-west by Muzaffargarh district. According to the census conducted in 1998, the total population of the district was 2.8 million, as compared to about 2 million in 1981. It is largerly a rural district as only around 23% people live in the urban areas. According to a 2008 estimate, the population of the district has risen to about 3.5 million. Table 1: Population Profile of Jhang District 1951 1961 1972 1981 1998 Total 8,63,000 10,65,000 15,55,000 19,71,000 28,34,545 Rural - - - - 21,71,555 Urban - - - - 6,62,990 Urban population as %age of Total - - - - 23.4% Source: Population Census Organization, Statistics Division, Government of Pakistan , District Census Report of Jhang, Islamabad, August 2000. Jhang is one of the oldest districts of the Punjab province. Currently, the district consists of 4 tehsils: Ahmad Pur Sial, Chiniot, Jhang and Shorkot. -

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr. # Branch Name City Name Branch Address Code Show Room No. 1, Business & Finance Centre, Plot No. 7/3, Sheet No. S.R. 1, Serai 1 0001 Karachi Main Branch Karachi Quarters, I.I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi 2 0002 Jodia Bazar Karachi Karachi Jodia Bazar, Waqar Centre, Rambharti Street, Karachi 3 0003 Zaibunnisa Street Karachi Karachi Zaibunnisa Street, Near Singer Show Room, Karachi 4 0004 Saddar Karachi Karachi Near English Boot House, Main Zaib un Nisa Street, Saddar, Karachi 5 0005 S.I.T.E. Karachi Karachi Shop No. 48-50, SITE Area, Karachi 6 0006 Timber Market Karachi Karachi Timber Market, Siddique Wahab Road, Old Haji Camp, Karachi 7 0007 New Challi Karachi Karachi Rehmani Chamber, New Challi, Altaf Hussain Road, Karachi 8 0008 Plaza Quarters Karachi Karachi 1-Rehman Court, Greigh Street, Plaza Quarters, Karachi 9 0009 New Naham Road Karachi Karachi B.R. 641, New Naham Road, Karachi 10 0010 Pakistan Chowk Karachi Karachi Pakistan Chowk, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road, Karachi 11 0011 Mithadar Karachi Karachi Sarafa Bazar, Mithadar, Karachi Shop No. G-3, Ground Floor, Plot No. RB-3/1-CIII-A-18, Shiveram Bhatia Building, 12 0013 Burns Road Karachi Karachi Opposite Fresco Chowk, Rambagh Quarters, Karachi 13 0014 Tariq Road Karachi Karachi 124-P, Block-2, P.E.C.H.S. Tariq Road, Karachi 14 0015 North Napier Road Karachi Karachi 34-C, Kassam Chamber's, North Napier Road, Karachi 15 0016 Eid Gah Karachi Karachi Eid Gah, Opp. Khaliq Dina Hall, M.A. -

Punjab Development Statistics 2017 Preface

Punjab Development Statistics 2017 Preface Bureau of Statistics has been issuing this publication since 1972. The present edition is the 43rd in the series. It provides important statistics in respect of social, economic and financial sectors of the economy at aggregate as well as sectoral levels. This publication contains data on almost all sectors of the Provincial economy with their break-up by Tehsil, District & Division as far as possible. Eight tables on Monthly Electricity and Gas Consumption, Number of Zoo, Number of Bulldozers, Small and Mini Dams, Recognized Slaughter Houses and two provisional tables on population census 2017 are also added in this issue. It includes some national data on important subjects like Major Crops, Foreign Trade, Labour Force & Employment, National Accounts, Population, Price and Transport etc. It contains a 'Statistical Abstract' which gives a comparative picture of information on almost all Socio- Economic sectors of Pakistan and the Punjab. Key findings of Multiple Indicator Cluster Servey (MICS): 2014 of some of the Socio-Economic Indicators are also included in this edition viz-a-viz Education, Health, Housing and Socio-Economic Development by district. Every effort has been made to include the latest available data in this publication. It is hoped that this publication will be useful to the policy makers, planners, researchers, govt. departments and other users of Socio-Economic data in public as well as private sector. I am thankful to various Provincial Departments / Agencies / Federal Ministries / Divisional/District offices for supplying the required data. Without their co-operation, it would have not been possible to release this publication in time. -

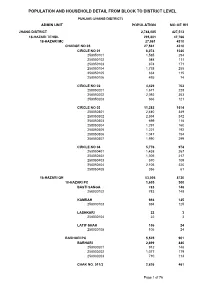

Jhang Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (JHANG DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH JHANG DISTRICT 2,744,085 427,513 18-HAZARI TEHSIL 295,801 47,766 18-HAZARI MC 27,561 4310 CHARGE NO 05 27,561 4310 CIRCLE NO 01 6,074 1020 258050101 1,585 294 258050102 548 111 258050103 874 171 258050104 1,738 255 258050105 834 115 258050106 495 74 CIRCLE NO 02 4,429 702 258050201 1,671 228 258050202 2,092 353 258050203 666 121 CIRCLE NO 03 11,282 1614 258050301 2,440 349 258050302 2,594 342 258050303 699 118 258050304 1,291 160 258050305 1,221 192 258050306 1,047 154 258050307 1,990 299 CIRCLE NO 04 5,776 974 258050401 1,438 267 258050402 1,306 217 258050403 570 109 258050404 2,106 320 258050405 356 61 18-HAZARI QH 53,006 8720 18-HAZARI PC 1,605 300 BASTI SANGA 783 148 258030102 783 148 KAMRAH 694 125 258030103 694 125 LASHKARI 22 3 258030104 22 3 LATIF SHAH 106 24 258030105 106 24 BARHARI PC 5,525 901 BARHARI 2,699 440 258030201 912 148 258030202 1,077 179 258030203 710 113 CHAK NO. 011/3 2,826 461 Page 1 of 76 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (JHANG DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 258030204 1,317 197 258030205 1,509 264 DAL PC 4,738 708 DAL 4,738 708 258030301 1,171 187 258030302 1,634 239 258030303 1,933 282 DHABBI PC 1,923 326 DHABBI 1,174 188 258030401 1,174 188 LUHRKA 449 89 258030404 449 89 SARWANI PATOANA 300 49 258030405 300 49 KOT NAULAN PC 5,142 937 FATEH SHAH 920 157 258030504 920 157 KOT NAULAN 4,096 755 258030501 2,510 465 258030502 1,586 290 SHAH MAHMUD 126 25 -

S.R.O. No.---/2011.In Exercise Of

PART II] THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JANUARY 9, 2021 39 S.R.O. No.-----------/2011.In exercise of powers conferred under sub-section (3) of Section 4 of the PEMRA Ordinance 2002 (Xlll of 2002), the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority is pleased to make and promulgate the following service regulations for appointment, promotion, termination and other terms and conditions of employment of its staff, experts, consultants, advisors etc. ISLAMABAD SATURDAY, JANUARY 9, 2021 PART II Statutory Notifications (S. R. O.) GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN MINISTRY OF NATIONAL FOOD SECURITY AND RESEARCH NOTIFICATION Islamabad, the 6th January, 2021 S. R. O. (17) (I)/2021.—In exercise of the powers conferred by section 15 of the Agricultural Pesticides Ordinance, 1971 (II of 1971), and in supersession of its Notifications No. S.R.O. 947(I)/2002, dated the 23rd December, 2002, S.R.O. 1251 (I)2005, dated the 15th December, 2005, S.R.O. 697(I)/2005, dated the 28th June, 2006, S.R.O. 604(I)/2007, dated the 12th June, 2007, S.R.O. 84(I)/2008, dated the 21st January, 2008, S.R.O. 02(I)/2009, dated the 1st January, 2009, S.R.O. 125(I)/2010, dated the 1st March, 2010 and S.R.O. 1096(I), dated the 2nd November, 2010. The Federal Government is pleased to appoint the following officers specified in column (2) of the Table below of Agriculture Department, Government of the Punjab, to be inspectors within the local limits specified against each in column (3) of the said Table, namely:— (39) Price: Rs. -

Lessons Learned from Jhang, Pakistan

District-level Joint Sector Review and WASH Bottleneck Analysis Tool: Lessons Learned from Jhang, Pakistan SUMMARY In 2017, the Government of Pakistan rolled out Joint Sector Reviews (JSR) in four provinces in order to periodically assess the performance of the water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) sector. UNICEF, the Government, development partners, and civil society participated in the process, using the WASH Bottleneck Analysis Tool (WASH-BAT) as a guiding framework. The WASH-BAT, which was designed by UNICEF with inputs from WASH sector stakeholders, was used to facilitate joint identification and prioritisation of sector bottlenecks and create an action plan for their removal. The WASH-BAT covers different sub-sectors (e.g. urban water supply, rural water supply, urban sanitation, rural sanitation, urban hygiene, and rural hygiene) and different levels of implementation (e.g. national, provincial and district). The WASH-BAT has already proven to be an effective tool in assessing the WASH sector bottlenecks, at both provincial and national levels in Pakistan. During the past three years, it has become evident that bottlenecks also exist at the grassroots level, hence the need for district JSRs. With DFID support, UNICEF and the Government of Punjab conducted a district-level JSR in Jhang District, where implementation of the Accelerated Sanitation and Water for All (ASWA-2) project is underway. This field note describes how the JSR was conducted in Jhang District, using WASH-BAT. Key WASH bottlenecks in Jhang District are described, along with proposed actions for mitigation and the removal of identified impediments. Introduction A JSR is a periodic process that brings together different WASH stakeholders and government to In 2016, Pakistan’s Ministry of Climate Change engage in dialogue; review the status, progress (MoCC), in collaboration with provincial and performance; as well as make decisions on governments and WASH sector partners, priority actions aimed at improving access to organised a capacity development workshop to roll WASH services. -

Riverine Flood Assessment in Jhang District in Connection with ENSO and Summer Monsoon Rainfall Over Upper Indus Basin for 2010

Riverine flood assessment in Jhang district in connection with ENSO and summer monsoon rainfall over Upper Indus Basin for 2010 Bushra Khalid1, 2, 3, 4, Bueh Cholaw1, Débora Souza Alvim5, Shumaila Javeed6, Junaid Aziz Khan7, Muhammad Asif Javed8, Azmat Hayat Khan9 Corresponding author’s email: [email protected] Corresponding author’s mobile: 0092-3315719701 1International Center for Climate and Environment Sciences, Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029, China 2Earth System Physics, The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics, Trieste, Italy 3Department of Environmental Science, International Islamic University, Islamabad, Pakistan 4International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Laxenburg, Austria 5Center for Weather Forecasting and Climate Studies, National Institute for Space Research, Cachoeira Paulista, São Paulo, Brazil 6Department of Mathematics, COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Islamabad, Pakistan 7Institute of Geographical Information System (IGIS), National University of Science and Technology (NUST), Islamabad, Pakistan 8Department of Humanities, COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Islamabad, Pakistan 9Pakistan Meteorological Department, Quetta, Pakistan 1 1 Abstract 2 3 Pakistan has experienced severe floods over the past decades due to climate 4 variability. Among all the floods, the flood of 2010 was the worst in history. 5 This study focuses on the assessment of 1) riverine flooding in the district Jhang 6 (where Jhelum and Chenab rivers join, and the district was severely flood 7 affected) and 2) south Asiatic summer monsoon rainfall patterns and anomalies 8 considering the case of 2010 flood in Pakistan. The land use/cover change has 9 been analyzed by using Landsat TM 30 m resolution satellite imageries for 10 supervised classification, and three instances have been compared i.e., pre 11 flooding, flooding, and post flooding. -

Updated MDP-Jhang-17Th Sep 2014

RAIN/FLOODS 2014: JHANG, PUNJAB 1 MINI DISTRICT PROFILE FOR RAPID NEEDS ASSESSMENT September 17th, 2014 Rains/Floods 2014: Jhang District Profile September 2014 iMMAP-USAID District at a Glance Administrative DivisionRajanpur - Reference Map Police Stations (http://www.lahorepolice.gov.pk/) Attribute Value District/tehsil Knungo Patwar Number of Mouzas Sr. No. Police Station Phone No. Population (2014 est) 2,698,974 Circles/ Circles/ 1 SDPO City Circle 0092-47-9200233 Male 1,401,682 (52%) Supervisory Tapas Total Rural Urban Partly Forest Un- 2 Kotwali 0092-47-9200316 Female 1,297,292 (48%) Tapas urban populated 3 Sadar Jhang 0092-47-9200313 DISTRICT 22 213 360 211 92 40 17 Rural 2,115,978 (18%) 4 City Jhang 0092-47-9200271 LAHORE CITY 10 76 115 51 40 15 9 Urban 7,746,264 (82%) LAHORE 5 SDPO Sadar Circle 0092-47-9200312 12 137 245 160 52 25 8 Tehsils 4 CANTT 6 Mochiwala 0092-47-7642100 UC 84 Source: Punjab Mouza Statistics 2008 7 Qadir Pur 0092-477-640010 Revenue Villages/Mouza 1,036 8 Masan 0092-477-000416 Area (Sq km) 6,282 Road Network Infrastructure: District Roads: 1,244.41 (km), NHWs: 48.43 (km), Prov. Highways: 9 Athara Hazari 0092-477-645510 113.6 (km) R&B Sector: 245.31 (km), Farm to Market: 343.47 (km), District Council Roads: 493.6 (km) Registered Voters (ECP) 645,448 10 Kot Shakir 0092-477-226300 District Route Length Literacy Rate 10+ (PSLM 2012-13) 52% Jhang to Faisalabad Jhang-Faisalabad Road 76.6 km 11 SDPO Shor Kot Circle 0092-475-310898 Jhang to Lahore Motorway/AH1 256 km 12 Shor Kot City 0092-475-310698 Departmental Focal Points Jhang to Multan Khanewal-Kabirwala Road 159 km 13 Shor Kot Cantt.