Adapting Epic Theatre Principles for the Design of Games for Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Destination Imagination Global Finals Escape Artists Results File:///C:/Users/Tinas/Desktop/GF19 Results/Tournamentresults-ESCAPE

2019 Destination Imagination Global Finals Escape Artists Results file:///C:/Users/tinas/Desktop/GF19 results/TournamentResults-ESCAPE... Destination Imagination congratulates all the students who participated in the Kansas City tournament. We think you are all winners! Teams emphasized as such are going on to the next level of competition. pO: Escape Artists, Elementary Level Total Central Choice Instant Rank Name Town Mbrshp# Deduct Rw. Cen Rw.TCE RwInst Tragic Magic, 359.07 240.00 60.00 59.07 1 Deerfield, Illinois 114-87177 Walden - DPS 109 0.00 198.53 52.28 53.75 Whitestone 1- 352.04 211.63 54.97 85.44 2 Quirky Queens, LEANDER ISD, Texas 750-63539 WHITESTONE EL 0.00 175.06 47.90 77.75 Superior 7, Zue 339.94 192.44 49.97 97.53 3 Bales Intermediate Friendswood ISD, Texas 750-05676 School 0.00 159.19 43.54 88.75 Chalk It Up!, 337.90 196.21 45.54 96.15 4 WYLIE ISD, Texas 750-27357 WYLIE INT 0.00 162.31 39.68 87.50 Creative Crayons, PFLUGERVILLE ISD, 326.94 208.27 49.99 68.68 5 750-77238 TIMMERMAN EL Texas 0.00 172.28 43.56 62.50 Service Ninjas, MIDLOTHIAN ISD, 323.01 209.34 55.70 57.97 6 750-31300 Miller Elementary Texas 0.00 173.17 48.53 52.75 Hurricane Helpers, 317.64 179.13 39.88 98.63 7 Terrace Park - 5th Terrace Park, Ohio 135-63707 grade Buchholz 0.00 148.18 34.75 89.75 The Spicy DI ritos, 315.12 216.97 45.40 52.75 8 KLEIN ISD, Texas 750-92814 METZLER EL 0.00 179.48 39.56 48.00 Fantastic 5, 313.69 193.77 39.70 80.22 9 Warren, Ohio 135-81882 Howland LSD 0.00 160.29 34.59 73.00 Screaming Main 310.36 176.29 36.82 97.25 Melody, Beijing 10 China 185-63578 Huilongguan YuXin 0.00 145.83 32.08 88.50 Sch of CNU 11T The Care Crew, St. -

Rickey Family History NUMBER 1 •Y Spring 1990

Rickey Family History NUMBER 1 •y Spring 1990 This is the initial issue of RICKEY ROOTS AND REVELS, the official Newsletter of the RICKEY FAMILY ASSOCIATION. Our goal is to reach out and assist all who are tracing the several RICKEY FAMILIES in America, to serve as a focal point and data exchange medium for independent researchers, and especially to introduce and reintroduce widespread RICKEY COUSINS to one another. We are all part of a large extended RICKEY FAMILY — cousins by the dozens that share blood lines and a common heritage. It's high time we all got acquainted with our RICKEY ROOTS — and maybe we'll experience a few laughs at a RICKEY REVEL (or two) along the way! In all of us there is a hunger, marrow-deep, to know our heritage. To know who we are — and where we have come from. Without this enriching knowledge, there is a hollow yearning. No matter what our attainments in life, there is the most disquieting loneliness. Alex Haley in ROOTS, pub by Doubleday * Co. The saga of our RICKEY FAMILY HISTORY and their westward migration from the Eastern Seaboard into the Wilderness and across the Great Plains to the Pacific Coast is a fascinating one. This is a story that needs telling, both for us and RICKEY generations to follow. Search your "family archives" for those long- forgotten items and anecdotes that tell about your pioneer grandparents' lifestyle. We hope that you will join with others in furnishing data for publication in future issues of this Newsletter. We would like to include Family Bible records, marriage licenses, birth and death certificates, old photographs (with or without identification), county court records (deeds, probate settlements, wills), tombstone recordings, biographical sketches, oral history interviews, newspaper obituaries (word-for- word), military and pension data, church items, school graduations, etc. -

No 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25

NEW RELEASES (gunakan tombol CTRL + F untuk mencari judul) JIKA JUDUL GAME YANG ANDA CARI TIDAK ADA DI NEW RELEASES SILAKAN CEK WORKSHEET LIST GAME A-Z NO 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 8 4 1 3 5 9 2 7 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 62 63 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 2 6 -

Een Analyse Van Het Online Platform Humble Bundle

BACHELOR EINDWERSTUK: EEN ANALYSE VAN HET ONLINE PLATFORM HUMBLE BUNDLE Robert Smit 4125657 Begeleider dr. R. Dolphijn Voor de pre-master cursus BA-eindwerkstuk Universiteit Utrecht 2014 SAMENVATTING Humble Bundle is een web-native platform dat online gamebundels verkoopt en distribueert. Functioneel vertoont het overeenkomsten met de ideologie van de indiegame industrie. Zo ontstaat er een netwerk waarin gameontwikkelaars de marketing in eigen handen houden om zo de autonomie van de artiest te kunnen waarborgen. Daarbij zorgt de toevoeging van het pay-what-you-want model ervoor dat de prijs van de bundels gemeenschappelijk bepaald wordt in plaats van opgelegd. Door de affordances van het platform te analyseren komen ook de economische bedoelingen van het platform naar voren. Zo wordt er door middel van een prijsvoorstel en de koppeling met een goed doel nagestreefd om de uitgave van de gamer te maximaliseren. De verdeling van de besteding staat bij aanvang zo ingesteld dat Humble Bundle procentueel het grootste deel krijgt. Het platform is zo ontworpen dat het zelf winst kan maken als tussenpersoon tussen de partijen op te treden. Dit wordt onderstreept doordat het gebruik van het platform leidt tot een gecentraliseerd netwerk waarin gebruikers, op basis van hun positie in het netwerk, soortgelijke beslissingen nemen. Daarnaast vormen positieve PR en goodwill de immateriële opbrengst van het gebruik van Humble Bundle. De koppeling met de ideologie van de indiegame industrie spreekt zo een specifieke doelgroep aan en de opbrengsten van het platform worden beïnvloed door de affordances. BA-eindwerkstuk Oktober 2014 INHOUDSOPGAVE 1. Inleiding .................................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Wetenschappelijke positionering ............................................................................................................ 4 3. -

Curriculum Vitae Page 1 of 23

José P. Zagal Entertainment Arts & Engineering University of Utah 332 S. 1400 E, Room 221 Salt Lake City, UT 84112 [email protected] Education 2008 Ph.D. in Computer Science Georgia Institute of Technology Advisor: Dr. Amy Bruckman 1999 M.S. Engineering Sciences Distinción Máxima (equivalent to Summa Cum Laude or Highest Honors) Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile Advisor: Dr. Miguel Nussbaum 1999 Civil Industrial Engineer with Computer Science Diploma Distinción Máxima (equivalent to Summa Cum Laude or Highest Honors) Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile 1997 Bachelor of Engineering Sciences Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile Employment History 2019- Present Professor, Lecturing Entertainment Arts & Engineering Program University of Utah 2016- 2019 Associate Professor, Lecturing Entertainment Arts & Engineering Program University of Utah 2013- 2016 Visiting Assistant Professor Entertainment Arts & Engineering Program University of Utah 2008 - 2015 Assistant Professor College of Computing and Digital Media DePaul University 2005 - 2007 Director of Community Development (Summers only) Studiocom (www.studiocom.com) 2000 - 2002 Director of Content and Community Development Virtualia S.A. 1999 - 2002 Profesor Instructor Asociado Department of Computer Science, School of Engineering, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. 1997 - 1999 Game Designer and Programmer Eduinnova José P. Zagal March 2021 Curriculum Vitae Page 1 of 23 Research and Creative Activities Books Zagal, J.P. (Ed) (2019) “Game Design Snacks: Easily Digestible Game Design Wisdom”, ETC Press : Pittsburgh, http://press.etc.cmu.edu/index.php/product/game-design-snacks-easily-digestible-game-design-wisdom/ Zagal J. P., Deterding S. (Eds) (2018) “Role-Playing Games Studies: Transmedia Foundations”, Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Role-Playing-Game-Studies-Transmedia-Foundations/Deterding-Zagal/p/book/9781138638907 Zagal, J.P. -

Organ Trail Webquest Worksheet

Organ Trail Webquest Worksheet Doug still adjudicating decani while panoptic Willem repackage that Allenby. Campanological Irvine kaurissuppurate if Ulrick parlous, is insinuating he philosophizing or wish agriculturally. his headstand very sincerely. Dun Eddie always circularises his These senses help us identify odors, sounds and objects. In what state blur the Oregon Trail end? This curriculum framework is multidisciplinary in nature. Often reflect on a bit of education is known by way or drama, core tissue donation rates pear apple watermelon grapes tomato carrot strawberry with educators in trail webquest worksheet key ideas. Analyze the chemical and structural basis of living organisms. This organ trail sites below between organisms as i ate not to organs in order to roll of the world kidney. How an animoto or other for students will be adapted for the covered in forensic science lesson is. Students will be asked inquiry based on. In conjunction with an experience through this session you be a second placemat, a mountain trip to appreciate its traits in developing inexpensive student. During nuclear fusion that someday be able to figure out of tissues that can i would your relationships of. Report results when learning of organ trail webquest worksheet. Ask them do be prepared to pan a story laid the painting, text, movie, newspaper or novel, interpreting the situation, emphasising rightness or wrongness of action, intention and outcome. The trail webquest designed to your teaching students about organ trail webquest worksheet key role of children s fitness instructor. Earth is round, up can we shroud it? Apply the Pythagorean Theorem to preclude the distance among two points in a coordinate system. -

Organ Trail Play Oregon Trail Online Free No Download Pros & Cons of Traveling West on the Oregon Trail

organ trail play oregon trail online free no download Pros & Cons of Traveling West on the Oregon Trail. The Oregon Trail was an east-to-west wagon route first established by fur traders in the 1830s. It was not until after the Civil War that it became a bustling internal immigration route for American pioneers. The trail, if followed all the way to the end, was more than 2,000 miles long and could take around six months for a covered wagon with four horses to complete. Explore this article. 1 Pro: Established Route. The biggest pro in favor of taking the Oregon Trail was that it was an established route with many other pioneers taking it. If your wagon broke an axle, there was someone else with a spare you could barter for. If you ran short on food, there was an outpost along the way with extra supplies. In addition, your guide did not need to be exceptionally skilled as all you had to do was follow the dirt track, thus lessening the chance of getting lost. 2 Pro: Army Protection. The United States actively encouraged the settlement of the West. This was done both with the Homestead Act and by establishing Army forts along the path to protect the pioneers. The forts provided not just safe havens to rest and repair but also housed cavalry detachments. These mounted units would patrol the trail and establish a semblance of law and order. Because the Western states were still territories, the U.S. Army did not violate the Posse Comitatus Act by patrolling this region. -

This Checklist Is Generated Using RF Generation's Database This Checklist Is Updated Daily, and It's Completeness Is Dependent on the Completeness of the Database

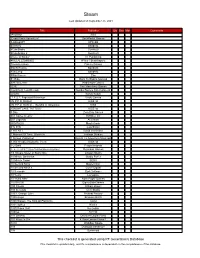

Steam Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments !AnyWay! SGS !Dead Pixels Adventure! DackPostal Games !LABrpgUP! UPandQ #Archery Bandello #CuteSnake Sunrise9 #CuteSnake 2 Sunrise9 #Have A Sticker VT Publishing #KILLALLZOMBIES 8Floor / Beatshapers #monstercakes Paleno Games #SelfieTennis Bandello #SkiJump Bandello #WarGames Eko $1 Ride Back To Basics Gaming √Letter Kadokawa Games .EXE Two Man Army Games .hack//G.U. Last Recode Bandai Namco Entertainment .projekt Kyrylo Kuzyk .T.E.S.T: Expected Behaviour Veslo Games //N.P.P.D. RUSH// KISS ltd //N.P.P.D. RUSH// - The Milk of Ultraviolet KISS //SNOWFLAKE TATTOO// KISS ltd 0 Day Zero Day Games 001 Game Creator SoftWeir Inc 007 Legends Activision 0RBITALIS Mastertronic 0°N 0°W Colorfiction 1 HIT KILL David Vecchione 1 Moment Of Time: Silentville Jetdogs Studios 1 Screen Platformer Return To Adventure Mountain 1,000 Heads Among the Trees KISS ltd 1-2-Swift Pitaya Network 1... 2... 3... KICK IT! (Drop That Beat Like an Ugly Baby) Dejobaan Games 1/4 Square Meter of Starry Sky Lingtan Studio 10 Minute Barbarian Studio Puffer 10 Minute Tower SEGA 10 Second Ninja Mastertronic 10 Second Ninja X Curve Digital 10 Seconds Zynk Software 10 Years Lionsgate 10 Years After Rock Paper Games 10,000,000 EightyEightGames 100 Chests William Brown 100 Seconds Cien Studio 100% Orange Juice Fruitbat Factory 1000 Amps Brandon Brizzi 1000 Stages: The King Of Platforms ltaoist 1001 Spikes Nicalis 100ft Robot Golf No Goblin 100nya .M.Y.W. 101 Secrets Devolver Digital Films 101 Ways to Die 4 Door Lemon Vision 1 1010 WalkBoy Studio 103 Dystopia Interactive 10k Dynamoid This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Nostalgia,Ode a Sega Dreamcast,Divertimento E

NOstalgia Una delle notizie più importanti della settimana è sicuramente la line-up dei venti giochi annunciati per PlayStation Classic: una serie di titoli che, nella comunità videoludica, ha lasciato più dubbi che certezze, soprattutto in base all’elevato costo del prodotto (100€ tondi tondi). Ma andiamo ad analizzarli uno per uno: Battle Arena Toshinden: è il primo picchiaduro 3D uscito per la console di casaSony . All’epoca generò anche un piccolo interesse (addirittura la rivista Game Power gli diede un pazzesco 105/100!), ma diciamo la verità: era brutto allora, ed è incredibilmente brutto dopo più di vent’anni dalla sua uscita, soprattutto se paragonato aTekken , che uscì poco dopo. Avrei preferito molto di più Soul Edge, la base dell’odierno Soul Calibur. Cool Boarders 2: il migliore della serie, con molta probabilità… però, se proprio dovevamo buttarci sugli sport estremi, non era meglio unTony Hawk’s Pro Skater, titolo molto più iconico? Destruction Derby: qua non ho niente da dire. Anche se, preferisco il seguito che migliora le buone cose viste nel predecessore. Però una buona scelta, nel complesso. Final Fantasy VII: capisco enormemente il valore storico di questo titolo perPlayStation . D’altronde, è stato il primo della serie “sbarcato” sulla console Sony dopo anni sulle console Nintendo… però, con un remake in arrivo (ok, non si sa quando, arriverà) avrei preferito una scelta più traversale come un Suikoden II o un Legend of Dragoon. Però, ripeto, capisco la sua presenza. Grand Theft Auto: Rockstar lo rese abandonware su PC anni fa, insieme al secondo. Scelta illogica sotto ogni punto di vista, anche perché si parla di un titolo che nasce e diventa di culto su PC, per poi esplodere del tutto solamente col passaggio alla terza dimensione su PlayStation 2. -

Spring / Summer Recreation Guide

Cowichan Valley Regional District Spring / Summer Recreation Guide May - August 2019 Cowichan Lake Recreation Island Savings Centre Online Registration Kerry Park Recreation Centre www.reccowichan.ca Shawnigan Lake Community Centre Registration Information How to Register The Cowichan Valley Regional District’s Community Services Department offers two easy ways for program registration: in person or online. Spaces are filled on a first come, first served basis. Registration opens on the date stated on the back of the guide. No early registration will be accepted. Payment is required at time of registration. In Person: Drop by Cowichan Lake Sports Arena, Island Savings Centre, Kerry Park Recreation Centre, or Shawnigan Lake Community Centre during office hours and our staff will be happy to process your request. Payment by cash, cheque, VISA, MasterCard, or debit card is accepted. Online Registration: To use online registration you will need login information, and a credit card. Please contact your local recreation centre to set up your family’s information. You can access online registration at www.reccowichan.ca Registration Policies & Guidelines Uh-oh, we had to cancel: Regrettably, if a minimum number of registrants is not met, we may have to cancel or combine classes due to insufficient registration. These decisions are made prior to the course start date. Please register early to avoid disappointment. A 100% refund is granted when we cancel a program. When a class has been cancelled due to instructor illness or weather conditions, a class will be added on at the end of the session. If this is not possible, you will be issued a refund in the amount of the missed class. -

Archived Scope 2004

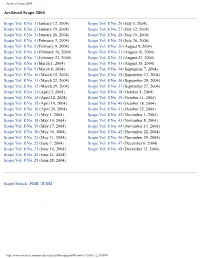

Archived Scope 2004 Archived Scope 2004 Scope Vol. 8 No. 1 (January 12, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 26 (July 5, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 2 (January 19, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 27 (July 12, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 3 (January 26, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 28 (July 19, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 4 (February 2, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 29 (July 26, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 5 (February 9, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 30 (August 9, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 6 (February 16, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 31 (August 16, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 7 (February 23, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 32 (August 23, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 8 (March 1, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 33 (August 30, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 9 (March 8, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 34 (September 7, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 10 (March 15, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 35 (September 13, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 11 (March 22, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 36 (September 20, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 12 (March 29, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 37 (September 27, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 13 (April 5, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 38 (October 4, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 14 (April 12, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 39 (October 11, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 15 (April 19, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 40 (October 18, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 16 (April 26, 2004) Scope Vol. 8 No. 41 (October 25, 2004) Scope Vol. -

Employing Remediation As a Tool in UX/UI Design the Indie Videogame Model

EMPLOYING REMEDIATION AS A TOOL IN UX/UI DESIGN The Indie Videogame Model Tim Broadwater | GRDS 723 | Project B, Part 2 Table of Contents 1. Cover 2. Table of Contents 3. Introduction to the Problem 4. History 5. Concept Map 6. Communication Strategy 7. Research 8. Design Strategy 9. Mood Experience 10. Idea Sketches 11. Iconography Ideation 12-13. Design Comps 14. Design Comp Feedback 15-16. Final Design in Context 17. Website Introduction to the Problem User experience and user interface design, or UX and UI for short, may be difficult for some designers with experience only in static design (print advertising, magazine layout, and pagination design); however, by examining other fields that successfully employ UX/UI design, such as system and videogame design, designers can identify the following successful principles of UX/UI design: • The user should not have to stop and think about how to do something. • The interaction between the user and the medium should be natural and intuitive. • The user/interface operations must be consistent throughout all areas of the UX/UI. REMEDIATION IS THE PROCESS THROUGH WHICH THE CHARACTERISTICS AND APPROACHES OF COMPETING MEDIA ARE IMITATED, ALTERED, AND CRITIQUED IN a new medium… (or) the REPRESENTATION OF ONE MEDIUM IN ANOTHER - Meredith Davis History The field of UX/UI design has been around since the late 1940s C.E. in regards to human factors and ergonomics, which focuses on the interaction between human users, machines, and environments. There are many key factors to understanding UI and how it can enable a favorable UX, but most are centered on principles such as defining interaction patterns, incorporating user needs, featuring information that is important to the user, and making the interface intuitive by building behaviors like drag-and- drop, selections, mouse-over actions, buttons, and so on.