Nevada Legislature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethics Summary Final(2)

ETHICS COMMISSION REPORT November 2009 SUMMARY After giving the Ethics Commission report to the House of Representatives earlier this afternoon, Governor Sanford has decided to make public that same document as part of his continued efforts to both fully cooperate with the Commission and share as much relevant information with the public as possible. We believe that when the full story is told, it will be clear that this Administration has kept a consistent eye out for the taxpayer. It is important to remember that we are still in the early stages of the ethics process, and that we continue to support the Ethics Commission being able to complete their work and then release all findings to the public. The steps are as follows: first, a preliminary report to determine whether or not there was anything even worth looking at (which was not unexpected as allegations had made headlines for months); next, will come our chance to shed light on any remaining questions when the Commission holds hearings; then, their conclusion will follow. Through this process, we will have the opportunity to show that Governor Sanford has complied fully with the law. For instance, that he has simply followed a legislatively audited and long held practice regarding overseas travel – the same practice accepted over the last 30 years as business class tickets were used by South Carolina Commerce staff, Members of the House and Senate, governors and Secretaries of Commerce on overseas investment trips. We feel vindicated that in this case the issues of probable cause are limited to about three dozen minor, technical matters that do not include any allegations of criminal conduct. -

2003 Directory of State and Local Government

DIRECTORY OF STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT Prepared by RESEARCH DIVISION LEGISLATIVE COUNSEL BUREAU January 2003 Revised October 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Please refer to the Alphabetical Index to the Directory of State and Local Gov- ernment for a complete list of agencies. NEVADA STATE GOVERNMENT ORGANIZATION CHART .................D-9 CONGRESSIONAL DELEGATION .................................................. D-11 DIRECTORY OF STATE GOVERNMENT CONSTITUTIONAL OFFICERS: Attorney General ....................................................................... D-13 State Controller ......................................................................... D-17 Governor ................................................................................. D-18 Lieutenant Governor ................................................................... D-21 Secretary of State ....................................................................... D-22 State Treasurer .......................................................................... D-23 EXECUTIVE BOARDS ................................................................. D-24 UNIVERSITY AND COMMUNITY COLLEGE SYSTEM OF NEVADA .... D-25 EXECUTIVE BRANCH AGENCIES: Department of Administration ........................................................ D-30 Administrative Services Division ............................................... D-30 Budget Division .................................................................... D-30 Economic Forum ................................................................. -

Assignments) by 9Am Tuesday, 9/8

1 Writing 20, True(?) Crime Dr. Odendahl-James, Fall 2009 Blog 1 – Writing in Conversation with Sources Bloggers whose work will be under discussion in class should submit their documents to the Course Blog (under Course Information) by 9am Tuesday, 9/8. All other posters should submit their posts to the Individual Bog (under Assignments) by 9am Tuesday, 9/8. Late posts will not be counted as received. Bloggers whose work will be under discussion, please bring to class either your laptops or a hard copy of the post so you can read aloud. I will also bring my computer so the class can read along. Blog Commenters have until 5pm Wednesday, 9/9 to post feedback to the Course Bog. Late comments will not receive credit. Step 1: Choose one of the readings discussed in class on September 1: Jean Murley‘s ―Introduction‖ and the first part of Karen Halftone‘s ―Murder Story as Mystery.‖ Step 2: Select three significant passages from whichever reading you selected for Step 1. You decide what makes a passage ―significant‖; the length of each passage should not be more than about 4-5 full sentences. Re-type those passages into a Word document and spend some time brainstorming about what you think makes each passage important to your thinking about the topic of ―true crime‖. This step is usually called ―pre-writing.‖ Step 3. Out of that brainstorming, in a new Word document, write, in your own words, a 250-300 word analysis of one of the ―significant‖ passages you selected in Step 2. -

Assembly Committee Minutes

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE ASSEMBLY COMMITTEE ON ELECTIONS, PROCEDURES, ETHICS, AND CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENTS Seventy-Third Session March 15, 2005 The Committee on Elections, Procedures, Ethics, and Constitutional Amendments was called to order at 3:53 p.m., on Tuesday, March 15, 2005. Co-Chairman Harry Mortenson presided in Room 3142 of the Legislative Building, Carson City, Nevada. Exhibit A is the Agenda. All exhibits are available and on file at the Research Library of the Legislative Counsel Bureau. COMMITTEE MEMBERS PRESENT: Mrs. Ellen Koivisto, Co-Chairwoman Mr. Harry Mortenson, Co-Chairman Mr. Marcus Conklin, Co-Vice Chairman Mr. Mo Denis Mrs. Heidi S. Gansert Ms. Chris Giunchigliani Mr. Brooks Holcomb Ms. Kathy McClain Mr. Harvey J. Munford Mr. Bob Seale Mr. Scott Sibley COMMITTEE MEMBERS ABSENT: Mr. Bob McCleary, Co-Vice Chairman (excused) Mrs. Sharron Angle (excused) GUEST LEGISLATORS PRESENT: Assemblywoman Genie Ohrenschall, Assembly District No. 12, Clark County (part) STAFF MEMBERS PRESENT: Michelle Van Geel, Committee Policy Analyst Sheila Sease, Personal Attaché to Assemblyman Mortenson Assembly Committee on Elections, Procedures, Ethics, and Constitutional Amendments March 15, 2005 Page 2 Celeste Gunther, Committee Attaché OTHERS PRESENT: Carole Vilardo, President, Nevada Taxpayers Association Patricia Cafferata, Former State Treasurer John Wagner, President, Burke Consortium of Carson City Kathy Augustine, Nevada State Controller Kim Huys, Acting Chief Deputy, Office of the Controller, State of Nevada Teresa Moiola, -

Guide to the Lori Lipman Brown Papers

Guide to the Lori Lipman Brown Papers This finding aid was created by Hannah Robinson and Angela Moor on November 26, 2018. Persistent URL for this finding aid: http://n2t.net/ark:/62930/f1d60w © 2018 The Regents of the University of Nevada. All rights reserved. University of Nevada, Las Vegas. University Libraries. Special Collections and Archives. Box 457010 4505 S. Maryland Parkway Las Vegas, Nevada 89154-7010 [email protected] Guide to the Lori Lipman Brown Papers Table of Contents Summary Information ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Note ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Scope and Contents Note ................................................................................................................................ 4 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................. 5 Related Materials ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Names and Subjects ....................................................................................................................................... -

14613 Hon. Donald A. Manzullo Hon. Jon C. Porter

July 17, 2006 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS, Vol. 152, Pt. 11 14613 clearly the preferred alternative. Commercial THANK YOU, HECTOR BARRETO, time high. All this was accomplished while health plans have long recognized the clinical FOR A JOB WELL DONE transforming the SBA into an agency to meet value and cost-effectiveness of home infusion the challenges of the 21st century. Change is therapy, and full and proper coverage of home HON. DONALD A. MANZULLO hard but Mr. Barreto made the courageous de- infusion therapy is commonplace among these OF ILLINOIS cision to have the SBA operate more like the payers. Medicare stands virtually alone in its IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES private sector than a bureaucracy. Doing more with less should be praised. not condemned, antiquated coverage policies that discourage Monday, July 17, 2006 particularly in this tough budget environment. the use of a therapy that in actuality should be Mr. MANZULLO. Mr. Speaker, last Monday Then, Hurricanes Katrina, Rita. and Wilma promoted for its cost savings, safety, clinical was the last day in office for Hector Barreto, violently struck the gulf coast last year. It was effectiveness, and convenience. At a time the second-longest serving SBA Administrator as if a swath of complete devastation 100 when there is a growing awareness of the in its 53-year history. Last week, there was a miles wide ripped through our country from need to prevent or limit inpatient hospital stays reception in honor of former Administrator Boston to Chicago. Again. Administrator for our Nation’s elderly, we believe this legisla- Barreto with a broad spectrum of the small Barreto and his team in the Office of Disaster tion is extremely timely. -

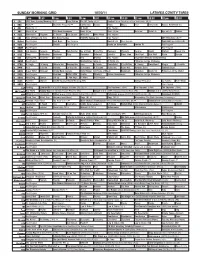

Sunday Morning Grid 10/30/11 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/30/11 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face/Nation The NFL Today (N) Å Football Miami Dolphins at New York Giants. (N) Å 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference George House House Paid Travel Cafe Access Hollywood (N) 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week-Amanpour News (N) Å News (N) Å News Å Vista L.A. Eye on L.A. Motion 9 KCAL Tomorrow’s Kingdom K. Shook Joel Osteen Ministries Mike Webb Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Paid Program UFC Primetime (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Best of L.A. Paid Program From Hell ›› (2001) (R) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program Hecho en Guatemala Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curiosity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Cuisine Cook’s Kitchen Sweet Life 28 KCET Cons. Wubbulous Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Lidsville Place, Own Chef Paul Burt Wolf Pépin Venetia 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Paid Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tu Al Punto (N) Fútbol de la Liga Mexicana 40 KTBN K. Hagin Ed Young Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Guide to the Nevada State Senator Bob Coffin Records of the Kathy Augustine Impeachment Trial

Guide to the Nevada State Senator Bob Coffin Records of the Kathy Augustine Impeachment Trial This finding aid was created by Joyce Moore on July 06, 2018. Persistent URL for this finding aid: http://n2t.net/ark:/62930/f1mp6v © 2018 The Regents of the University of Nevada. All rights reserved. University of Nevada, Las Vegas. University Libraries. Special Collections and Archives. Box 457010 4505 S. Maryland Parkway Las Vegas, Nevada 89154-7010 [email protected] Guide to the Nevada State Senator Bob Coffin Records of the Kathy Augustine Impeachment Trial Table of Contents Summary Information ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Notes .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents Note ................................................................................................................................ 4 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................. 4 Names and Subjects ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... -

A Snail's Tale

Summer 2002 A Snail’s Tale: The amazing story of survival in North American springs and wetlands Across the western United States and northern Mexico, thousands of small springs, seeps, and wetlands provide the sole source of moisture in miles of inhospitable desert. Many of these small water sources are virtually unknown, while others have been IN THIS ISSUE: fully developed for urban use, agriculture, recreation, native wildlife preservation, and even geothermal energy generation. Some of these springs gained notoriety as important waypoints in the American western migration of the nineteenth century. Others, for many You Mean We Have millennia, have filled a critical role as the only a Choice? point of relief in a parched landscape, with page 6 the most meager only barely darkening the Spring hopes eternal. Dr. Don Sada surface of the ground. has studied the aquatic ecosystems of In the past few years, a remarkable story more than three hundred Great Basin and Mojave Desert springs in an effort to of ecological transformation, adaptation, preserve them for the future. and survival spanning millions of years has Photo by Laurie Sada been emerging from these small water holes, President’s Medals crusty seeps, and muddy playas. But it is a tale Awarded that is losing chapters as fast as they are being page 9 discovered. Within the most arid landscape of North America, scientists have discovered one of the largest collections of aquatic diversity existing anywhere in the world, let alone in a desert. At the same time, scientists are watching this newly revealed diversity disappear at what may be the fastest rate of any ecology on the North American continent. -

Intro Sec 1.Indd

State of Nevada Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2002 Kathy Augustine State Controller Kathy Augustine State Controller The Offi ce of State Controller was created when Nevada became a state in 1864. The Controller is one of Nevada’s six constitu- tional offi cers elected statewide to a four-year term. Ms. Augustine was sworn in as Nevada’s fi rst female State Controller on January 4, 1999. She serves as a member of the State Board of Finance, the Department of Transportation Board of Directors and the Executive Branch Audit Committee. As Chief Fiscal Offi cer of the State, she is empowered to represent the State in fi scal matters and her position is critical in main- taining a checks-and-balance system in state fi nances. The Controller ensures compliance with state fi scal and federal revenue laws. She administers the state accounting system in order to provide, fair, accurate, consistent, and timely fi nancial reporting in accordance with standards set forth by the Govern- mental Accounting Standards Board. Her offi ce also prepares the Popular and Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports, pays employee salaries, processes claims against the state and administers the debt collection program. Comprehensive Annual Report State For the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2002 ooff Nevada Table of Contents INTRODUCTORY SECTION PAGE Letter of Transmittal ......................................................................................................................... 1 Constitutional Of fi cers ...................................................................................................................... -

Women in Nevada History

Revised, Corrected, and Expanded Edition A Digital-Only Document Betty J. Glass 2018 WOMEN IN NEVADA HISTORY An Annotated Bibliography of Published Sources Revised, corrected, and expanded edition Betty J. Glass © 2018 Nevada Women’s History Project Dedicated to the memory of Jean Ford (1929-1998), founder of the Nevada Women’s History Project, whose vision has given due recognition to the role women played and are continuing to play in the history of Nevada. Her tireless leadership and networking abilities made the original project possible. Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................... i Annotated Bibliography ................................................................................................ 1 Index of Nevada Women’s Names ........................................................................... 327 Index of Topics .......................................................................................................... 521 Index of Nevada Women’s Organizations ............................................................... 620 Index of Race, Ethnic Identity of Nevada Women .................................................. 666 Genre Index ............................................................................................................... 672 Introduction This annotated bibliography is a product of the Nevada Women’s History Project (NWHP), a statewide educational Nevada non-profit corporation, 501c3. Our -

DAY 22 79 That Has Been Rectified

78 JOURNAL OF THE SENATE THE TWENTY-SECOND DAY CARSON CITY (Wednesday), December 1, 2004 Senate called to order at 8:14 a.m. President Hunt presiding. Roll called. All present. Prayer by the Chaplain, Pastor Albert Tilstra. O God, our help in ages past, our hope for years to come, our shelter from the stormy blast, and our eternal home! In this the day that You have made, help us to appreciate its beauty and to use its opportunities rightly. Deliver us, we pray, from the tyranny of trifles. May we give our best thought and attention to what is important, that we may accomplish something worthwhile. Teach us how to listen to Your promptings, and save us from floundering in indecision that wastes time, subtracts from our peace, divides our efficiency and multiplies our troubles. These things we ask from Him who delights to answer prayers. AMEN. Pledge of allegiance to the Flag. Senator Raggio moved that further reading of the Journal be dispensed with, and the President and Secretary be authorized to make the necessary corrections and additions. Motion carried. MOTIONS, RESOLUTIONS AND NOTICES Senator Raggio moved that the following persons be accepted as accredited press representatives, and that they be assigned space at the press table and allowed the use of the appropriate media facilities: NEW YORK TIMES: John M. Broder; RENO GAZETTE-JOURNAL: Lisa Tolda. Motion carried. Senator Raggio moved that the Senate resolve itself into a Committee of the Whole for the purpose of hearing the Articles of Impeachment against Nevada State Controller Kathy Augustine, with Senator Amodei as Chair of the Committee of the Whole.