State Statutory Responses to Criminal Street Gangs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House of Representatives 3030

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE 4719 By Mr. POWERS: A bill <H.R. 8695) granting an in 3044. By Mr. STRONG of Pennsylvania: Petition of the crease of pension to Bella J. Roberts; to the Committee on Johnstown Ministerial Association, the Cambria County Invalid Pensions. Civic Club, and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union By Mr. WILCOX: A bill <HR. 8696) for the relief of of Johnstown, Pa., favoring the Patman motion picture bill, Jeter J. McGee; to the Committee on Claims. H.R. 6097; to the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Com By Mr. PARKER. Joint resolution (H.J.Res. 300) for the merce. relief of John T. Garity; to the Committee on Claims. 3045. By Mr. SUTPHIN: Petition of the New Jersey branch, second division, Railway Mail Association, protesting PETITIONS, ETC. against enforced lay-off of regular postal employees and the curtailment of substitute employment; to the Committee on Under clause 1 of rule XXII, petitions and papers were the Post Office and Post Roads. laid on the Clerk's desk and referred as follows: 3029. By Mr. AYRES of Kansas: Petitions of citizens of 3046. By Mr. WERNER: Petition of citizens of Dell Rap Wichita, Kans., prntesting against the so-called " Tugwell ids, S.Dak., urging passage of House bill 7019, providing a. measure ", which proposes to amend the Pure Food and pension for the aged; to the Committee on Labor. Drugs Act; to the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 3030. By Mr. CARTER of California: Petition of the Oak land District of the California Council of Dads Clubs for the SATURDAY, MARCH 17, 1934 permanent preservation of the United States frigate Consti The House met at 12 o'clock noon. -

1996 Annual Report

Los Angeles Police Department Annual Report 1996 Mission Statement 1996 Mission Statement of the Los Angeles Police Department Our mission is to work in partnership with all of the diverse residential and business communities of the City, wherever people live, work, or visit, to enhance public safety and to reduce the fear and incidence of crime. By working jointly with the people of Los Angeles, the members of the Los Angeles Police Department and other public agencies, we act as leaders to protect and serve our community. To accomplish these goals our commitment is to serve everyone in Los Angeles with respect and dignity. Our mandate is to do so with honor and integrity. Los Angeles Mayor and City Council 1996 Richard J. Riordan, Mayor Los Angeles City Council Back Row (left to right): Nate Holden, 10th District; Rudy Svorinich, 15th District; Rita Walters, 9th District; Richard Alarcón, 7th District; Laura Chick, 3rd District; Hal Bernson, 12th District; Michael Feuer, 5th District; Mark Ridley-Thomas, 8th District; Jackie Goldberg, 13th District; Richard Alatorre, 14th District Front Row (left to right): Ruth Galanter, 6th District; Joel Wachs, 2nd District; John Ferraro, President, 4th District; Mike Hernandez, 1st District; Marvin Braude, President Pro-Tempore, 11th District Board of Police Commissioners 1996 Raymond C. Fisher, President Art Mattox, Vice-President Herbert F. Boeckmann II, Commissioner T. Warren Jackson, Commissioner Edith R. Perez, Commissioner Chief's Message 1996 As I review the past year, the most significant finding is that for the fourth straight year crime in the City of Los Angeles is down. -

Issue 12.Pdf

w Welcome This is issue twelve LPM has entered its third year of existence and there are some changes this year. Instead of releasing an issue every two months we are now a quarterly magazine, so a new issue is released every three months. We also are happy to welcome Annie Weible to our writing staff, we are psyched that she has joined our team. We will continue to bring you interesting articles and amazing stories. Paranormal - true crime- horror In this Issue The Legends of Alcatraz 360 Cabin Update Part two The Dybbuk Box The Iceman Aleister Crowley The Haunting of Al Capone Horror Fiction The visage of Alcatraz conjures visions of complete and utter isolation. The forlorn wails of intrepid seagulls beating against the craggy shore. A stoic reminder of the trials of human suffering, the main prison rises stark against the roiling San Francisco Bay. The Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary began its storied history in 1910 as a United States Army prison before transforming into a federal prison in 1934. Since its inception, Alcatraz held the distinction of being one of America’s toughest prisons, often being touted as “escape proof”. During its time as an active prison, Alcatraz held some of the most problematic prisoners. Notable characters held in Alcatraz includes; Al Capone, Machine Gun Kelley and Robert Stroud, among just a few. Alphonse Gabriel Capone, also known as Scarface, was an American gangster. Scarface was known for his brutality following the Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre in Chicago in which seven rival gang members were gunned down by Capone’s men. -

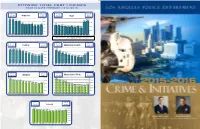

Crimes and Initiatives 2015

‘15 vs ‘05 Total Part I Crime ‘15 vs ‘14 ‘15 vs ‘05 Rape ‘15 vs ‘14 Homicide 120,000 Rape 116,532 1,800 103,492 1,649 489 480 100,000 1,600 500 2000 1,512 1,400 395 80,000 384 1649 1,200 1,105 400 1512 1,059 60,000 1,004 1,000 312 1500 949 293 297 299 903 923 936 828 283 40,000 260 764 800 251 300 11051059 1004 600 949 903 923 936 20,000 1000 828 764 400 200 - 200 - 100 500 2014 2015 92,096 92,096 0 0 2005 2006 2007 2008CITYWIDE2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 TOTAL2015 PART2005 2006 2007 2008 I2009 CRIMES2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 *Rape Stats prior to 2014 were updated to include additional Crime Class Codes YEAR to DATE THROUGH 12/31/2015 that have been added to the UCR Guidelines for the crime of Rape. ‘15 vs ‘05 ‘15 vs ‘14 ‘15 vs ‘05 ‘15 vs ‘14 Homicide Robbery ‘15 vs ‘05AggravatedRape AssaultsRobbery ‘15 vs ‘14 Homicide ‘15 vs ‘05 ‘15 vs ‘14 489 16,000 Rape 489 480 500 480 2000 500 Aggravated Assaults 2000 14,353 14,353 15000 13,797 20000 18,000 13,797 1649 14,000 13,481395 13,422 13,481 13,422 384 395 1512 16,376 1649 384 12,217 16,000 12,217 16,376 12,000 400 400 14,634 1512 10,924 12000 14,634 14,000 312 10,924 10,077 1500 13,569 1500 293 297 299 312 13,569 10,000 15000 12,926 10,077 8,983 8,935 11,798 283 1105 12,926 293 297 299 12,000 260 1059 7,885 7,940 283 11,798 8,000 1105 10,638 89,83 251 8,935 300 1004 949 260 300 1059 10,615 903 923 936 251 1004 10,000 7,885 7,940 9000 10,638 828 10,615 949 9,344 903 8,843 923 936 764 6,000 1000 8,329 1000 9,344 8,843 10000 828 8,000 8,329 7,624 764 200 7,624 4,000 200 6000 6,000 2,000 500 4,000 500 100 5000 100 3000 - 2,000 - 0 0 0 0 92,096 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 201392,0962014 2015 0 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 20140 2015 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2005200520062006200720072008200820092009201020102011201120122012201320132014201420152015 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 *Rape Stats prior to 2014 were updated to include additional Crime Class Codes that have been added to the UCR Guidelines for the crime of Rape. -

How the Mob and the Movie Studios Sold out the Hollywood Labor Movement and Set the Stage for the Blacklist

TRUE-LIFE NOIR How the Mob and the movie studios sold out the Hollywood labor movement and set the THE CHICAGO WAY stage for the Blacklist Alan K. Rode n the early 1930s, Hollywood created an indelible image crooked law enforcement, infected numerous American shook down businesses to maintain labor peace. Resistance The hard-drinking Browne was vice president of the Local of the urban gangster. It is a pungent irony that, less than metropolises—but Chicago was singularly venal. Everything by union officials was futile and sometimes fatal. At least 13 2 Stagehands Union, operated under the umbrella of IATSE a decade later, the film industry would struggle to escape and everybody in the Windy City was seemingly for sale. Al prominent Chicago labor leaders were killed; and not a single (The International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, the vise-like grip of actual gangsters who threatened to Capone’s 1931 federal tax case conviction may have ended his conviction for any criminals involved.Willie Bioff and George Moving Picture Technicians, Artists and Allied Crafts, here- bring the movie studios under its sinister control. reign as “Mr. Big,” but his Outfit continued to grow, exerting Browne were ambitious wannabes who vied for a place at after referred to as the IA). He had run unsuccessfully for the Criminal fiefdoms, created by an unholy trinity its dominion over various trade unions. Mobsters siphoned the union trough. Russian-born Bioff was a thug who served IA presidency in 1932. Bioff and Browne recognized in each Iof Prohibition-era gangsters, ward-heeling politicians, and off workers’ dues, set up their cohorts with no-show jobs, and the mob as a union slugger, pimp, and whorehouse operator. -

Nixon's Caribbean Milieu, 1950–1968

Dark Quadrant: Organized Crime, Big Business, and the Corruption of American Democracy Online Appendix: Nixon’s Caribbean Milieu, 1950–1968 By Jonathan Marshall “Though his working life has been passed chiefly on the far shores of the continent, close by the Pacific and the Atlantic, some emotion always brings Richard Nixon back to the Caribbean waters off Key Biscayne and Florida.”—T. H. White, The Making of the President, 19681 Richard Nixon, like millions of other Americans, enjoyed Florida and the nearby islands of Cuba and the Bahamas as refuges where he could leave behind his many cares and inhibitions. But he also returned again and again to the region as an important ongoing source of political and financial support. In the process, the lax ethics of its shadier operators left its mark on his career. This Sunbelt frontier had long attracted more than its share of sleazy businessmen, promoters, and politicians who shared a get-rich-quick spirit. In Florida, hustlers made quick fortunes selling worthless land to gullible northerners and fleecing vacationers at illegal but wide-open gambling joints. Sheriffs and governors protected bookmakers and casino operators in return for campaign contributions and bribes. In nearby island nations, as described in chapter 4, dictators forged alliances with US mobsters to create havens for offshore gambling and to wield political influence in Washington. Nixon’s Caribbean milieu had roots in the mobster-infested Florida of the 1940s. He was introduced to that circle through banker and real estate investor Bebe Rebozo, lawyer Richard Danner, and Rep. George Smathers. Later this chapter will explore some of the diverse connections of this group by following the activities of Danner during the 1968 presidential campaign, as they touched on Nixon’s financial and political ties to Howard Hughes, the South Florida crime organization of Santo Trafficante, and mobbed-up hotels and casinos in Las Vegas and Miami. -

One Beverly Hills Approved by Council

BEVERLYPRESS.COM INSIDE • Beverly Hills approves budget Sunny, with pg. 3 highs in the • Fire on Melrose 70s pg. 4 Volume 31 No. 23 Serving the Beverly Hills, West Hollywood, Hanock Park and Wilshire Communities June 10, 2021 WeHo calls for LASD audit One Beverly Hills approved by council n If county fails to act, city may step in n Bosse clashes with BY CAMERON KISZLA Association to audit the contracts of Mirisch on affordable all cities partnered with the LASD, housing issue The West Hollywood City which include West Hollywood. Council took action in regards to The council’s vote, which was BY CAMERON KISZLA the allegations of fraud made part of the consent calendar, comes against the Los Angeles County after the LASD was accused in a The Beverly Hills City Council Sheriff’s Department. legal filing last month of fraudu- on June 8 gave the One Beverly The council on June 7 unani- lently billing Compton, another city Hills project the necessary mously called for the Los Angeles that is contracted with the depart- approvals, but not without some County Board of Supervisors and ment, for patrolling the city less conflict between council members. the inspector general to work with See page The 4-1 vote was opposed by the California Contract Cities LASD 31 Councilman John Mirisch, who raised several issues with the pro- ject, including that more should be done to create affordable housing. rendering © DBOX for Alagem Capital Group The One Beverly Hills project includes 4.5 acres of publicly accessible Mirisch cited several pieces of evidence, including the recently botanical gardens and a 3.5-acre private garden for residents and completed nexus study from hotel guests. -

An Introduction to Gangs in Virginia

An Introduction to Gangs in Virginia Office of the Attorney General Photographs Provided By: Virginia Gang Investigators Association Virginia Department of Corrections Fairfax County Gang Unit Pittsylvania County Sheriff’s Office Boys & Girls Clubs of Virginia Galax Police Department Richmond Police Department unless otherwise specified Videos Provided By Dr. Al Valdez and are NOT from Virginia Kenneth T. Cuccinelli, II Attorney General of Virginia American Violence Contains some graphic content Overview I. Facts About Gangs II. Identifying Signs of Gang Association III. Safety Issues for EMS Part I FACTS ABOUT GANGS Gangs In History Gangs have been present throughout human history. Blackbeard and other pirates plundered the Caribbean during the 1600’s and 1700’s. The word “Thug” dates back to India from around 1200, and refers to a gang of criminals. Gangs In History Irish gangs were a part of riots in NYC during the 1860’s. Gangs like “The Hole in the Wall Gang” and Billy the Kid’s Gang robbed in the Southwest during the 1800’s. Gangs In History Picture from The United Northern and Southern Knights of the Ku Klux Klan website with members in Virginia. This from a 2007 cross lighting ceremony. Al Capone’s Organization and the Ku Klux Klan are examples of prominent gangs in the 1900’s. Gangs Today Many of today’s gangs can trace their roots to the later half of the 20th Century. El Salvador Civil War – 1980’s. The Sleepy Lagoon Boys – 1940’s Zoot Suit Riots. The “Truth” in Numbers There are at least 26,500 gangs and 785,000 gang members in the U.S. -

Measuring the Effects of Video Surveillance on Crime in Los Angeles

Measuring the Effects of Video Surveillance on Crime in Los Angeles Prepared for the California Research Bureau CRB-08-007 May 5, 2008 Aundreia Cameron Elke Kolodinski Heather May Nicholas Williams CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................................................4 THE RISE OF CCTV SURVEILLANCE IN CALIFORNIA...................................................6 The Prevalence of Video Surveillance in California ...........................................................7 California Crime Rates, Video Surveillance and Spending.................................................8 Privacy, Efficacy and Public Opinion................................................................................10 Arguments against CCTV on Privacy Grounds…………………………………. 10 Arguments for CCTV on Efficacy Grounds…………………………………….. 11 Privacy versus Efficacy in California…………………………………………... 13 META-ANALYSIS OF EXISTING EMPIRICAL WORK ....................................................14 Crime Deterrence...............................................................................................................14 Crime Detection, Mitigation and Prosecution ...................................................................17 Local Characteristics of CCTV Implementation ...............................................................18 CCTV, CRIME AND POLICING IN LOS ANGELES...........................................................18 Crime and Policing in Los Angeles ...................................................................................19 -

California Urban Crime Declined in 2020 Amid Social and Economic

CALIFORNIA URBAN CRIME DECLINED IN 2020 AMID SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC UPHEAVAL Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice Mike Males, Ph.D., Senior Research Fellow Maureen Washburn, Policy Analyst June 2021 Research Report Introduction In 2020, a year defined by the COVID-19 pandemic, the crime rate in California’s 72 largest cities declined by an average of 7 percent, falling to a historic low level (FBI, 2021). From 2019 to 2020, 48 cities showed declines in Part I violent and property felonies, while 24 showed increases. The 2020 urban crime decline follows a decade of generally falling property and violent crime rates. These declines coincided with monumental criminal justice reforms that have lessened penalties for low-level offenses and reduced prison and jail populations (see Figure 1). Though urban crime declined overall in 2020, some specific crime types increased while others fell. As in much of the country, California’s urban areas experienced a significant increase in homicide (+34 percent). They also saw a rise in aggravated assault (+10 percent) and motor vehicle theft (+10 percent) along with declines in robbery (-15 percent) and theft (-16 percent). Preliminary 2021 data point to a continued decline in overall crime, with increases continuing in homicide, assault, and motor vehicle theft. An examination of national crime data, local economic indicators, local COVID-19 infection rates, and select murder and domestic violence statistics suggests that the pandemic likely influenced crime. Figure 1. California urban crime rates*, 2010 through 2020 3,500 3,000 -14% 2,500 -16% 2,000 Public Safety Proposition 47 Proposition 57 1,500 Realignment 1,000 500 -3% 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Part I Violent Property Sources: FBI (2021); DOF (2021). -

4.14 Public Services Fire Protection and Emergency

West Adams New Community Plan 4.14 Public Services Draft EIR 4.14 PUBLIC SERVICES This section provides an overview of public services and evaluates the impacts associated with the proposed project. Topics addressed include fire protection and emergency services, police protection services, public schools, and parks and other public services. The proposed project is evaluated in terms of the adequacy of existing and planned facilities and personnel to meet any additional demand generated by the implementation of the West Adams New Community Plan. FIRE PROTECTION AND EMERGENCY SERVICES REGULATORY FRAMEWORK Federal There are no federal fire protection and emergency services regulations applicable to the proposed project. State There are no State fire protection and emergency services regulations applicable to the proposed project. Local City of Los Angeles General Plan, Framework and Safety Elements. The City of Los Angeles General Plan provides policies related to growth and development by providing a comprehensive long-range view of the City as a whole. The General Plan provides a comprehensive strategy for accommodating long-term growth. Goals and policies that apply to all development within the City of Los Angeles include a balanced distribution of land uses, adequate housing for all income levels, and economic stability. The Citywide General Plan Framework (Framework), an element of the City of Los Angeles General Plan adopted in December 1996 and amended in August 2001, is intended to guide the City’s long-range growth and development through the year 2010. The Framework includes goals, objectives, and policies that are applicable to fire protection and emergency services (Table 4.14-1). -

Mara Salvatrucha: the Most Dangerous Gang in America

Mara Salvatrucha: The Deadliest Street Gang in America Albert DeAmicis July 31, 2017 Independent Study LaRoche College Mara Salvatrucha: The Deadliest Street Gang in America Abstract The following paper will address the most violent gang in America: Mara Salvatrucha or MS-13. The paper will trace the gang’s inception and its development exponentially into this country. MS-13’s violence has increased ten-fold due to certain policies and laws during the Obama administration, as in areas such as Long Island, New York. Also Suffolk County which encompasses Brentwood and Central Islip and other areas in New York. Violence in these communities have really raised the awareness by the Trump administration who has declared war on MS-13. The Department of Justice under the Trump administration has lent their full support to Immigration Custom Enforcement (ICE) to deport these MS-13 gang members back to their home countries such as El Salvador who has been making contingency plans to accept this large influx of deportations of MS-13 from the United States. It has been determined by Garcia of Insight.com that MS-13 has entered into an alliance with the security threat group, the Mexican Mafia or La Eme, a notorious prison gang inside the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. The Mexican Drug Trafficking Organization [Knights Templar] peddles their drugs throughout a large MS-13 national network across the country. This MS-13 street gang is also attempting to move away from a loosely run clique or clikas into a more structured organization. They are currently attempting to organize the hierarchy by combining both west and east coast MS-13 gangs.