Expropriation: Compensating the Landowner to the Full Extent of His Loss Allen Crigler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collection 93 Osborne, Ollie Tucker (1911-1994)

Collection 93 Osborne, Ollie Tucker (1911-1994). Papers, 1927-1985 22 feet Ollie Tucker Osborne's papers detail the activities of one of Louisiana's leading advocates of women's rights during the 1970s. Ollie was extremely active in the League of Women Voters and the Evangeline ERA coalition. She attended conferences or workshops throughout the South. She was appointed to the 1977 state women's convention in Baton Rouge and was elected a state delegate to the national convention in Houston. She helped organize or coordinate a number of workshops and conferences in Louisiana on women's rights. Much of this often frenetic activity can be seen through her papers. Osborne was born in northern Louisiana and educated at Whitmore College and Louisiana State University. Just before graduation she married Louis Birk, a salesman for McGraw-Hill & Company, and moved to New York. After several false starts Osborne launched a career in public relations and advertising which she pursued for twenty years. This included some pioneering work in television advertising. Following the sudden death of Birk in 1952, Osborne returned to Louisiana where she met and married Robert Osborne, an English professor at the University of Southwestern Louisiana (now the University of Louisiana at Lafayette). During the next two decades she was busy as president of Birk & Company, a publisher of reading rack pamphlets. Osborne's introduction to politics at the state level was as an official League of Women Voters observer of the 1973 Constitutional Convention. Early in the year she determined that some on-going communication link was necessary to allay voter fear and apathy about the new constitution. -

Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential Election Matthew Ad Vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2011 "Are you better off "; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election Matthew aD vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Caillet, Matthew David, ""Are you better off"; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election" (2011). LSU Master's Theses. 2956. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2956 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ―ARE YOU BETTER OFF‖; RONALD REAGAN, LOUISIANA, AND THE 1980 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History By Matthew David Caillet B.A. and B.S., Louisiana State University, 2009 May 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people for the completion of this thesis. Particularly, I cannot express how thankful I am for the guidance and assistance I received from my major professor, Dr. David Culbert, in researching, drafting, and editing my thesis. I would also like to thank Dr. Wayne Parent and Dr. Alecia Long for having agreed to serve on my thesis committee and for their suggestions and input, as well. -

Investigative Report

General Excellence Louisiana Press Association CENTRALCENTRAL CITYCITY National Newspaper Assn. Investigative Report ® How the Election Was Stolen & The Leader NEWSNEWSNovember 19, 2020 • Vol. 23 No. 12 • 16 Pages • Circ. 10,000 • Central City News on Facebook • [email protected] • 225-261-5055 The Scandal of the Century How Election Was Stolen While the mainstream media has crowned former Vice President Joe Analysis Shows Biden as “President-elect,” the facts on the ground are quite different, at least in two swing states that have Obvious Fraud been called for Vice President Biden — Georgia and Pennsylvania. By Computer in In those two states, a careful analysis of the data shows that both states voted for President Trump States of GA, PA and the election was stolen. It was fraud by computer. Woody Jenkins Since Dominion and Smartmatic Editor have control of the voting machines, the software, and the reporting of the CENTRAL — Election Day in the results, it should be up to the owners United States, held this year on and officials of those two entities to Tuesday, Nov. 3, 2020, was really explain how it was done. But it was a series of 51 separate elections — done, as will be shown. one in each of the 50 states and the Unraveling this mystery begins District of Columbia. The vote total with The New York Times. After in each determines how the electoral polls closed on Election Day, The votes of that state or district will be Times begin to report the results hour cast in the Electoral College on Dec. President Donald Trump Former Vice President Joe Biden after hour. -

News Capital City

Baton Rouge’s CAPITALCAPITAL CITYCITY Community Newspaper Cell Phones Record ViolenceStudents, Teachers Secretly in Recorded Schools Cell Phone Videos That Capture Violence in EBR Schools. See Page 2 NEWSNEWS® Thursday, June 13, 2013 • Vol. 22, No. 12 • 16 Pages • Serving Baton Rouge • www.capitalcitynews.us • 225-261-5055 Coach Miles Goes ‘Over the Edge’ Key Issues: Education, Crime Serious Debate On Proposal To Incorporate Southeast BR Only Voters Decide SE Backers Say Issue of Whether to Create Municipality La. Constitution SOUTHEAST — The battle to create May Not Need a new community school system in the southeast part of East Baton To Be Amended Rouge Parish is about to take on a SOUTHEAST — Supporters of entirely new dimension. the proposed Southeast Ba- Now supporters of the new ton Rouge Community School district say they are considering District said Wednesday the launching a drive to incorporate recently-completed legislative Southeast Baton Rouge into a new session was far more successful municipality. than most people realize. Norman Browning, chairman of Norman Browning, chair- LSU coach Les Miles rappelled off One American Place to promote adoption. Local Schools for Local Children, man of Local Schools for Lo- said there are at least three reasons cal Children, said the passage to form a new municipality: of SB 199 has placed the new LSU Coach Says It’s Time to Get • Facilitate creation of the school district in the Louisi- Southeast school district ana Revised Statutes. “That is Serious about Adoption of Kids • Allow Southeast residents to done. We passed the legislation through four committee hear- BATON ROUGE control planning and zoning within — The Louisiana Family Forum has set a goal of the school district, and ings and both houses of the leg- Family Forum says more than helping at least 100 of those chil- • Serve as a bulwark against islature. -

Committee's Report

COMMITTEE’S REPORT (filed by committees that support or oppose one or more candidates and/or propositions and that are not candidate committees) 1. Full Name and Address of Political Committee OFFICE USE ONLY LOUISIANA REPUBLICAN PARTY Report Number: 15251 11440 N. Lake Sherwood Suite A Date Filed: 9/8/2008 Baton Rouge, LA 70816 Report Includes Schedules: Schedule A-1 2. Date of Primary 10/4/2008 Schedule A-2 Schedule A-3 This report covers from 12/18/2007 through 8/25/2008 Schedule B Schedule D 3. Type of Report: Schedule E-1 180th day prior to primary 40th day after general Schedule E-3 90th day prior to primary Annual (future election) X 30th day prior to primary Monthly 10th day prior to primary 10th day prior to general Amendment to prior report 4. All Committee Officers (including Chairperson, Treasurer, if any, and any other committee officers) a. Name b. Position c. Address ROGER F VILLERE JR. Chairperson 838 Aurora Ave. Metairie, LA 70005 DAN KYLE Treasurer 818 Woodleigh Dr Baton Rouge, LA 70810 5. Candidates or Propositions the Committee is Supporting or Opposing (use additional sheets if necessary) a. Name & Address of Candidate/Description of Proposition b. Office Sought c. Political Party d. Support/Oppose On attached sheet 6. Is the Committee supporting the entire ticket of a political party? X Yes No If “yes”, which party? Republican Party 7. a. Name of Person Preparing Report WILLIAM VANDERBROOK CPA b. Daytime Telephone 504-455-0762 8. WE HEREBY CERTIFY that the information contained in this report and the attached schedules is true and correct to the best of our knowledge , information and belief, and that no expenditures have been made nor contributions received that have not been reported herein, and that no information required to be reported by the Louisiana Campaign Finance Disclosure Act has been deliberately omitted . -

Thursday 11/18/10

Central’s DAiLy NEws CENtRALspEAks.com source CentralSpeaks.com Print Edition • Daily News At CentralSpeaks.com • 16 Pages • Thursday, November 18, 2010 Central WAS NOT Billed for Redaction of Records Jenkins’ Allegations “Reckless, False, & Defamatory,” According to City Attorney In a letter to Mayor Watts dated No- vember 12th, Central City Attorney Sheri Morris responded to an article written by Woody Jenkins in a local newspaper last week. In the article Jenkins claims Ms. Morris’ legal bills to the City “include substantial fees for the time she spent ‘redacting’ her pre- vious bills and then ‘unredacting’ those same bills.” In her letter Ms. Morris, who only last week was reconfi rmed by the City Council as Central’s City Attorney, addresses the entire process undertaken by the City in response to the records request for legal bills. The letter, presented in its entirety below, explains that by law Central’s attor- ney-client privilege must be protected, even in a public records request, and that only the City Council and Mayor can waive that privilege. The letter specifi cally refutes and calls “false” all claims by Jenkins that the City of Central was charged for the “redact- Photo by Expressions Photography ing” or “unredacting” of legal bills. On Veterans Day, the City of Central had its own Veterans Day service at Grace United Pentecostal Church on Ms. Morris asserts that the July and Hooper Road. The Mayor, several Councilmen, and many veterans were present. During the service, the vet- August invoices “refute Mr. Jenkins’ statements.” erans (pictured above) were recognized and honored. -

As Registrar Compares Every Signature, Spring Election for St

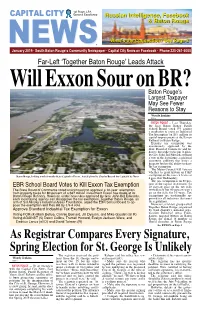

1st Place, LPA CAPITALCAPITAL CITYCITY General Excellence RussianRussian Intelligence,Intelligence, FacebookFacebook && BatonBaton RougeRouge What’sWhat’s thethe Connection?Connection? SeeSee PagePage 22 NEWS® NEWSJanuary 2019 • South Baton Rouge’s Community Newspaper • Capital City News on Facebook • Phone 225-261-5055 Far-Left ‘Together Baton Rouge’ Leads Attack Will Exxon Sour on BR? Baton Rouge’s Largest Taxpayer May See Fewer Reasons to Stay Woody Jenkins Editor BATON ROUGE - Last Thursday, the East Baton Rouge Parish School Board voted 5-4 against a resolution to grant an Industrial Tax Exemption on $67 million in capital improvements at the Exxon Refinery in Baton Rouge. Exxon’s tax exemption was unanimously approved by the State Board of Commerce and In- dustry, but under rules put in place by Gov. John Bel Edwards without a vote of the legislature, each local governing authority that levies a property tax has the ability to deny the tax exemption. The Metro Council will vote on whether to grant Exxon an ITEP Baton Rouge, looking north from the State Capitol to Exxon. Aerial photo by Charles Breard for Capital City News exemption on the taxes it levies at 4 p.m. this Wednesday. The tax exemption is on 80 per- cent of the capital investment. So EBR School Board Votes to Kill Exxon Tax Exemption 20 percent goes on the tax rolls The State Board of Commerce voted unanimously to approval a 10-year exemption immediately but 80 percent won’t from property taxes for 80 percent of a $67 million investment Exxon has made at its go on the rolls for 10 years. -

JBE Orders Ban Dancing in Louisiana

General Excellence Louisiana Press Association CENTRALCENTRAL CITYCITY National Newspaper Assn. VOTE3 Saturday, Aug. 15 Tiffany Foxworth District Judge School Tax Renewal ® Rebuild Central High School & The Leader NEWSNEWSAugust 2020 • Vol. 23 No. 8 • 20 Pages • Circ. 10,000 • Central City News on Facebook • [email protected] • 225-261-5055 Runofff Election Saturday, August 15 in Central DistrictCentral’s Judge, 15th Anniversary School Tax SAMPLE BALLOT District Judge Race: City of Central Liberal-Conservative Saturday, Aug. 15, 2020 Battle Could Decide All Voters Direction of Court District Judge 19th JDC Woody Jenkins YVETTE ALEXANDER (D)* Editor *Endorsed by Democratic Party CENTRAL - This Saturday, Aug. TIFFANY FOXWORTH (D)* 15, voters in Central, Baker, Zach- *Endorsed by Central City News ary, and Sherwood Forest will go Tax Renewal for to the polls to choose a new dis- Central School System trict judge between conservative To Rebuild Central High former Army Judge Alexander: Capt. Tiffany [ ] Yes* [ ] No Foxworth and Liberal City Judge Yvette Alexander Conservative Tiffany Foxworth *Endorsed by Central City News World Traveller at Taxpayer Expense liberal City LIBERAL-CONSERVATIVE SHOWDOWN for District Court judge in the Saturday, Trips to Hawaii, Italy, Judge Yvette Aug. 15 runoff election. Conservative attorney and former Army Capt. Tiffany Foxworth Morocco, South Africa Alexander. (right), who ran first in the primary, and liberal Baton Rouge City Court Judge Yvette Jamaica, and More Foxworth is Alexander (left) will face off. Conservative voters in Central could decide the outcome. See Page 6 pro-life, pro- JBE Orders family, pro- traditional marriage, pro-gun, a crime-fighter, pro-military and Tax Renewal Will Be Devoted Ban Dancing pro-veteran. -

1 Record Group 1 Judicial Records of the French

RECORD GROUP 1 JUDICIAL RECORDS OF THE FRENCH SUPERIOR COUNCIL Acc. #'s 1848, 1867 1714-1769, n.d. 108 ln. ft (216 boxes); 8 oversize boxes These criminal and civil records, which comprise the heart of the museum’s manuscript collection, are an invaluable source for researching Louisiana’s colonial history. They record the social, political and economic lives of rich and poor, female and male, slave and free, African, Native, European and American colonials. Although the majority of the cases deal with attempts by creditors to recover unpaid debts, the colonial collection includes many successions. These documents often contain a wealth of biographical information concerning Louisiana’s colonial inhabitants. Estate inventories, records of commercial transactions, correspondence and copies of wills, marriage contracts and baptismal, marriage and burial records may be included in a succession document. The colonial document collection includes petitions by slaves requesting manumission, applications by merchants for licenses to conduct business, requests by ship captains for absolution from responsibility for cargo lost at sea, and requests by traders for permission to conduct business in Europe, the West Indies and British colonies in North America **************************************************************************** RECORD GROUP 2 SPANISH JUDICIAL RECORDS Acc. # 1849.1; 1867; 7243 Acc. # 1849.2 = playing cards, 17790402202 Acc. # 1849.3 = 1799060301 1769-1803 190.5 ln. ft (381 boxes); 2 oversize boxes Like the judicial records from the French period, but with more details given, the Spanish records show the life of all of the colony. In addition, during the Spanish period many slaves of Indian 1 ancestry petitioned government authorities for their freedom. -

St. George Leader October 2020 October 2020 St

St.St. GeorgeGeorge LeaderLeader October 2020 • Vol. 2, No. 2 • 16 Pages • Circulation 30,000 online • Mail: P. O. Box 2, St. George, LA 70801 • 225-261-5055 Speaker, Senate President Refuse to Support Petition SAMPLE BALLOT St. George Tuesday, Nov. 3, 2020 Will Legislative Session Fail United States Senate Bill CASSIDY* (R) *Endorsed by Republican Party Dustin Murphy (R) To End Shutdown, Masking? Adrian PERKINS* (D) *Endorsed by Democratic Party Antoine Pierce (D) and 11 others Congress, 6th District Dartanyon (Daw) WILLIAMS* (D) *Endorsed by Democratic Party Garret GRAVES* (R) *Endorsed by Republican Party Shannon Sloan (L) Richard (Rpt) Torregan (NP) 1st Circuit Court of Appeal Chris Hester (R) Melanie Newkome JONES* (D) *Endorsed by Democratic Party Johanna R. LANDRENEAU* (R) *Endorsed by Republican Party Family Court Judge (Kathy) Reznik Benoit (R) Hunter GREENE* (R) Powers Kim by Photo *Endorsed by Republican Party LOUISIANA HOUSE CHAMBER — The Louisiana House of Representatives is ending its special session ostensibly designed to Mayor-President end Gov. John Bel Edwards’ emergency orders, but with some Republicans under the influence of the governor, that appears unlikely. Sharon Weston BROOME* (D) *Endorsed by Democratic Party Steve Carter (R) which would end the emergency As Businesses order, which has destroyed many (E Eric) Guirard (I) How Will It End? thousands of businesses in the state. C. Denise Marcelle (D) The Speaker is reportedly The governor’s mask order also Jordan PIAZZA* (R) Fold, Legislature *Endorsed by Republican Party preparing a petition of his remains in place, despite an Attor- Frank Smith III (R) own to lift the emergency ney General’s Opinion declaring Fails to Revoke order. -

High School Football in Coverage Area of Capital City News Thursday, Sept

Serving Baton Rouge CAPITAL CITY and City of Central CAPITAL CITY Hard Hat CapitalCapitalEdition AreaArea TradeTrade && IndustryIndustry GuideGuide •• ComingComing Sept.Sept. 2020 •• ToTo advertise,advertise, CallCall 261-5055261-5055 NEWSNEWS® Thursday, September 6, 2012 • Vol. 21, No. 2 • 24 Pages • Circulation 20,000 • www.capitalcitynews.us • Phone 225-261-5055 Twice AdoptedpMayor Pro-Tem Was Adopted Twice by Age 16 BATON ROUGE — The future didn’t look very bright for the little boy born to a 16-year-old unwed moth- Mike Walker as a boy and today er on Dec. 31, 1948, in the small Photo by Woody Jenkins Woody by Photo North Louisiana community of Weston. That wasn’t something COACH SID EDWARDS with son Jack Ryan who suffers from autisim, wife Beanie, and coach J. R. Owens. that was accepted, and babies like that were often given away. But the mother was the youngest in a family of five girls, and when Prep Football: Coach Sid Says Best Wins the girl’s father looked down at the newborn, he said, “I wanted a boy! We’ll keep him!” Don’t Always Come on Friday Nights So, instead of being given away CITY OF CENTRAL — Central High school coach ever to receive the who rarely talks about football — at birth, little Mike Hudson was head football coach Sid Edwards honor. Two years ago, he was even to his players. He talks to adopted by his grandfather and was honored recently as a Louisi- named Louisiana’s 5A Coach of them about things like character, grandmother and got to stay with ana Sports Legend, the only high the Year. -

Membership in the Louisiana House of Representatives

MEMBERSHIP IN THE LOUISIANA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 1812 - 2024 Revised – July 28, 2021 David R. Poynter Legislative Research Library Louisiana House of Representatives 1 2 PREFACE This publication is a result of research largely drawn from Journals of the Louisiana House of Representatives and Annual Reports of the Louisiana Secretary of State. Other information was obtained from the book, A Look at Louisiana's First Century: 1804-1903, by Leroy Willie, and used with the author's permission. The David R. Poynter Legislative Research Library also maintains a database of House of Representatives membership from 1900 to the present at http://drplibrary.legis.la.gov . In addition to the information included in this biographical listing the database includes death dates when known, district numbers, links to resolutions honoring a representative, citations to resolutions prior to their availability on the legislative website, committee membership, and photographs. The database is an ongoing project and more information is included for recent years. Early research reveals that the term county is interchanged with parish in many sources until 1815. In 1805 the Territory of Orleans was divided into counties. By 1807 an act was passed that divided the Orleans Territory into parishes as well. The counties were not abolished by the act. Both terms were used at the same time until 1845, when a new constitution was adopted and the term "parish" was used as the official political subdivision. The legislature was elected every two years until 1880, when a sitting legislature was elected every four years thereafter. (See the chart near the end of this document.) The War of 1812 started in June of 1812 and continued until a peace treaty in December of 1814.