A Little Larceny: Labor, Leisure and Loyalty in the '50S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background -

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 3

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 3 Film Soleil D.K. Holm www.pocketessentials.com This edition published in Great Britain 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ, UK Distributed in the USA by Trafalgar Square Publishing P.O.Box 257, Howe Hill Road, North Pomfret, Vermont 05053 © D.K.Holm 2005 The right of D.K.Holm to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may beliable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The book is sold subject tothe condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in anyform, binding or cover other than in which it is published, and without similar condi-tions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1–904048–50–1 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Book typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 5 Acknowledgements There is nothing -

Complete Film Noir

COMPLETE FILM NOIR (1940 thru 1965) Page 1 of 18 CONSENSUS FILM NOIR (1940 thru 1959) (1960-1965) dThe idea for a COMPLETE FILM NOIR LIST came to me when I realized that I was “wearing out” a then recently purchased copy of the Film Noir Encyclopedia, 3rd edition. My initial plan was to make just a list of the titles listed in this reference so I could better plan my film noir viewing on AMC (American Movie Classics). Realizing that this plan was going to take some keyboard time, I thought of doing a search on the Internet Movie DataBase (here after referred to as the IMDB). By using the extended search with selected criteria, I could produce a list for importing to a text editor. Since that initial list was compiled almost twenty years ago, I have added additional reference sources, marked titles released on NTSC laserdisc and NTSC Region 1 DVD formats. When a close friend complained about the length of the list as it passed 600 titles, the idea of producing a subset list of CONSENSUS FILM NOIR was born. Several years ago, a DVD producer wrote me as follows: “I'd caution you not to put too much faith in the film noir guides, since it's not as if there's some Film Noir Licensing Board that reviews films and hands out Certificates of Authenticity. The authors of those books are just people, limited by their own knowledge of and access to films for review, so guidebooks on noir are naturally weighted towards the more readily available studio pictures, like Double Indemnity or Kiss Me Deadly or The Big Sleep, since the many low-budget B noirs from indie producers or overseas have mostly fallen into obscurity.” There is truth in what the producer says, but if writers of (film noir) guides haven’t seen the films, what chance does an ordinary enthusiast have. -

TCM CFF 2012 Kim Novak Announcement

For Release: March 6, 2012 2012 TCM Classic Film Festival to Honor Kim Novak The 2012 TCM Classic Film Festival will honor actress Kim Novak with a multi-tiered celebration of her extraordinary career. Among the events, Novak will have her hand and footprints enshrined in concrete in front of Grauman's Chinese Theater. She will also join TCM host Robert Osborne for an in-depth conversation to be taped in front of a live audience for airing on TCM later. And she will introduce a screening of Alfred Hitchcock's suspenseful classic Vertigo (1958). The TCM Classic Film Festival takes place Thursday, April 12 – Sunday, April 15, in Hollywood. "From thrillers like Hitchcock's Vertigo, to romantic dramas such as Picnic, noirish classics like The Man with the Golden Arm, comedies such as Bell, Book and Candle and musicals like Pal Joey, Kim Novak has made us fall in love with her time and time again,” Osborne said. "Our celebration of Kim Novak and her career is certain to be one of the highlights of the 2012 TCM Classic Film Festival.” Novak and Osborne's conversation will air on TCM next year as an original special entitled Kim Novak: Live from the TCM Classic Film Festival. The chat will be taped Friday, April 13, at The Avalon, the latest venue to join the festival lineup. Built in 1927, the historic landmark has hosted the likes of Bob Hope, Jerry Lewis, Judy Garland, Bing Crosby, The Beatles, Fred Astaire, Jimmy Durant and Merv Griffin's iconic talk show. Kim Novak: Live at the TCM Classic Film Festival follows in the footsteps of previous Live from the TCM Classic Film Festival specials. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

Film Noir Database

www.kingofthepeds.com © P.S. Marshall (2021) Film Noir Database This database has been created by author, P.S. Marshall, who has watched every single one of the movies below. The latest update of the database will be available on my website: www.kingofthepeds.com The following abbreviations are added after the titles and year of some movies: AFN – Alternative/Associated to/Noirish Film Noir BFN – British Film Noir COL – Film Noir in colour FFN – French Film Noir NN – Neo Noir PFN – Polish Film Noir www.kingofthepeds.com © P.S. Marshall (2021) TITLE DIRECTOR Actor 1 Actor 2 Actor 3 Actor 4 13 East Street (1952) AFN ROBERT S. BAKER Patrick Holt, Sandra Dorne Sonia Holm Robert Ayres 13 Rue Madeleine (1947) HENRY HATHAWAY James Cagney Annabella Richard Conte Frank Latimore 36 Hours (1953) BFN MONTGOMERY TULLY Dan Duryea Elsie Albiin Gudrun Ure Eric Pohlmann 5 Against the House (1955) PHIL KARLSON Guy Madison Kim Novak Brian Keith Alvy Moore 5 Steps to Danger (1957) HENRY S. KESLER Ruth Ronan Sterling Hayden Werner Kemperer Richard Gaines 711 Ocean Drive (1950) JOSEPH M. NEWMAN Edmond O'Brien Joanne Dru Otto Kruger Barry Kelley 99 River Street (1953) PHIL KARLSON John Payne Evelyn Keyes Brad Dexter Frank Faylen A Blueprint for Murder (1953) ANDREW L. STONE Joseph Cotten Jean Peters Gary Merrill Catherine McLeod A Bullet for Joey (1955) LEWIS ALLEN Edward G. Robinson George Raft Audrey Totter George Dolenz A Bullet is Waiting (1954) COL JOHN FARROW Rory Calhoun Jean Simmons Stephen McNally Brian Aherne A Cry in the Night (1956) FRANK TUTTLE Edmond O'Brien Brian Donlevy Natalie Wood Raymond Burr A Dangerous Profession (1949) TED TETZLAFF George Raft Ella Raines Pat O'Brien Bill Williams A Double Life (1947) GEORGE CUKOR Ronald Colman Edmond O'Brien Signe Hasso Shelley Winters A Kiss Before Dying (1956) COL GERD OSWALD Robert Wagner Jeffrey Hunter Virginia Leith Joanne Woodward A Lady Without Passport (1950) JOSEPH H. -

Crime Wave for Clara CRIME WAVE

Crime Wave For Clara CRIME WAVE The Filmgoers’ Guide to the Great Crime Movies HOWARD HUGHES Disclaimer: Some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Published in 2006 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com In the United States and Canada distributed by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © Howard Hughes, 2006 The right of Howard Hughes to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. The TCM logo and trademark and all related elements are trademarks of and © Turner Entertainment Networks International Limited. A Time Warner Company. All rights reserved. © and TM 2006 Turner Entertainment Networks International Limited. ISBN 10: 1 84511 219 9 EAN 13: 978 1 84511 219 6 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress catalog card: available Typeset in Ehrhardt by Dexter Haven Associates Ltd, London Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International, -

July 2019 New Releases a JOHN HUGHES FILM a JOHN HUGHES

July 2019 New Releases A JOHN HUGHES FILMILM what’s PAGE inside featured exclusives 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately! 68 Vinyl Audio 3 CD Audio 11 FEATURED RELEASES JERRY LEE LEWIS - PERE UBU - THE PRETENDERS - THE KNOX PHILLIPS... LONG GOODBYE WITH FRIENDS Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 37 Non-Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 41 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 67 Order Form 74 Deletions and Price Changes 72 BONG OF THE LIVING WEIRD SCIENCE SHORTCUT TO 800.888.0486 DEAD (STEELBOOK) HAPPINESS 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 SEX AND BROADCASTING: JERRY LEE LEWIS - PERE UBU - www.MVDb2b.com A FILM ABOUT WFMU THE KNOX PHILLIPS SESSIONS: LONG GOODBYE (DVD/BOOK/7 INCH VINYL) THE UNRELEASED RECORDINGS KEEP MVD WEIRD! MVD’s quest for weird is never in question, that’s for sure! This month we unveil another in ARROW VIDEO’s spectacular deluxe versions of classic cult films with WEIRD SCIENCE. Director John Hughes offers a hefty dose of wacked-out Sci-Fi in this 1985 film starring Kelly LeBrock and Robert Downey Jr. Being a nerd isn’t so weird after Superwoman appears! Also available as a limited edition Steelbook. This summer, get blinded by WEIRD SCIENCE! A sharp month for Arrow, with their redux of the 1978 rock movie FM, depicting the glory days of free form radio. Stars Martin Mull and Cleavon Little. Corporate greed infiltrates the airwaves, followed by rock and roll rebellion! Infectious soundtrack, featuring several surviving dinosaurs. Tune in, but don’t tune out these other Arrow darts, including THE CHILL FACTOR (“snow, slaughter and Satan!”), THE LOVELESS (starring Willem Dafoe), and the drama of Olivia de Havilland in 1941’s HOLD BACK THE DAWN. -

Special Instructions for Ordering DVD's Or Videos

Mail-A-Book DVD Catalog Mail-A-Book Arrowhead Library System 5528 Emerald Avenue Mountain Iron MN 55768-2069 www.arrowhead.lib.mn.us [email protected] 218-741-3840 218-748-2171 (FAX) To Order Materials: • You must be qualify for this service. This tax-supported service from the Arrowhead Library System is available to rural residents, those who live in a city without a public library, and homebound residents living in a city with a public library. This service is available to residents of Carlton, Cook, Itasca, Koochiching, Lake, Lake of the Woods, & St. Louis Counties. Rural residents who live in the following Itasca County areas, are eligible for Mail-A-Book service only if they are homebound: Town of Arbo, Town of Blackberry, Town of Feely, Town of Grand Rapids, Town of Harris, Town of Sago, Town of Spang, Town of Wabena, City of Cohasset, City of La Prairie, and the City of Warba. Residents who are homebound in the cities of Virginia and Duluth are served by the city library. • Select your titles from one of our current catalogs. (If you would like something not listed in the catalogs– go to Interlibrary Loan instructions). • Materials can be ordered: 1. by e-mail at: [email protected], 2. by using the form on our web page at: www.arrowhead.lib.mn.us/mab/mabform.htm 3. or by regular mail with a letter, postcard, or an order card. • Print your name, address, county & zip code on each order. (Hint: Some patrons are using mailing address labels when ordering on our order cards.) Put your Arrowhead Library System Library Card number on your order (14-digit number). -

8.5 1776 1941 1984 Les Miserables Man

8.5 Adventure of Sherlock Holmes Alvarez Kelly 1776 Smarter Brother, the Amadeus 1941 Adventurers, the Amateur, the 1984 Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Amazing Mrs. Holliday Les Miserables Adventures of Marco Polo, the Amazon Trader, the Man from Independence, the Adventures of Mark and Brian Ambush at Cimarron Pass /locher, Felix Adventures of Martin Eden Amensson, Bibi …For I Have Sinned Advocates, the American Film Institute Salute to 11 Harrowhouse Affair in Reno William Wyler 1776 (musical) Against the Wall American Gigolo 1974- The Year in Pictures Age of Innocence, the American Hot Wax 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Agency American Job 2001: A Space Odyssey Aiello, Danny American Ninja 2 23 Paces to Baker Street Airport Ames, Leon 240- Robert Applicant Airport 1975 Ames, Michael 3 Women Akins, Claude Among the Living 48 hours Alaska Patrol Amorous Adventure of Moll 5 Against the House Albert, Edward Flanders, the 6 Day Bike Rider Alda, Alan Amos 'n' Andy 60 Minutes Aldrich, Gail Amos, John 633 Squadron Alessandro, Victor An American Album 711 Ocean Drive Alex in Wonderland An American Tail: Fievel Goes 7th Voyage of Sinbad, the Alexander Hamilton West A Peculiar Journey Alfred the Great Anatomy of a Murder A Walk in the Clouds Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves And Justice for All Abbott & Costello Alias Billy the Kid And the Angels Sing Abe Lincoln in Illinois Aliens Anderson, Bill About Last Night Alistair Cooke's America Anderson, Dame Judith Absent- Minded Professor, the All About Eve Anderson, Herbert Academy Awards All Ashore Anderson, -

Tytuł Nośnik Sygnatura Commando DVD F.1 State of Grace DVD F.2 Black Dog DVD F.3 Tears of the Sun DVD F.4 Force 10 from Navaro

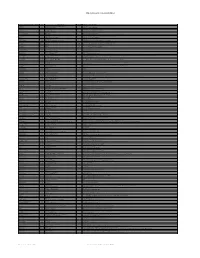

Tytuł Nośnik Sygnatura Commando DVD F.1 State of Grace DVD F.2 Black Dog DVD F.3 Tears of The Sun DVD F.4 Force 10 From Navarone DVD F.5 Palmetto DVD F.6 Predator DVD F.7 Hart's War DVD F.8 Three Kings DVD F.9 Antitrust DVD F.10 Prince of The City DVD F.11 Best Laid Plans DVD F.12 The Faculty DVD F.13 Virtuosity DVD F.14 Starship Troopers DVD F.15 Event Horizon DVD F.16 Outland DVD F.17 AI Artificial Intelligence DVD F.18 Aeon Flux DVD F19F.19 No Man's Land DVD F.20 War DVD F.21 Windtalkers DVD F.22 The Sea Wolves DVD F.23 Clay Pigeons DVD F.24 Stalag 17 DVD F.25 Young Lions DVD F.26 Where Eagles Dare DVD F.27 Patton DVD F.28 Das Boot - Director's Cut DVD F.29 The Thin Red Line DVD F.30 Robocop 3 DVD F.31 Screamers DVD F.32 Impostor DVD F.33 Prestige DVD F.34 Fracture DVD F.35 The Warriors DVD F.36 Color of Night DVD F.37 K-19 the Widowmaker DVD F.38 Scorpio DVD F.39 We Were Soldiers DVD F.40 Longest Day DVD F.41 Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas DVD F.42 Soldier of Orange DVD F.43 Pitch Black DVD F.44 Deathsport DVD F.45 Lathe of Heaven DVD F.46 Dark City DVD F.47 Enemy of The State DVD F.48 Quills DVD F.49 Mr Brooks DVD F.50 Almost Famous DVD F.51 Broadcast News DVD F.52 Great Escape DVD F.53 From Here to Eternity DVD F.54F.54 Soldier DVD F.55 Deja VU DVD F.56 Hellboy DVD F.57 Renaissance Paris 2054 DVD F.58 Donnie Darko DVD F.59 Dirty Dozen DVD F.60 King Rat DVD F.61 Gi Jane DVD F.62 Earth VS The Flying Saucers DVD F.63 Catch Me If You Can DVD F.64 Run Silent, Run Deep DVD F.65 Marathon Man DVD F.66 8MM DVD F.67 Panic Room DVD F.68 Two Minute Warning DVD F.69 Switchback DVD F.70 The Day of The Jackal DVD F.71 Cape Fear DVD F.72 Deliverance DVD F.73 Journey to The Far Side of The Sun DVD F.74 Being John Malkovich DVD F.75 Alien Nation. -

Southern Pacific Train Films

Film, Television and the Southern Pacific Railroad Movie or Television Series / Show Year Major Stars SPNG Southern Pacific Moment 3 Godfathers 1948 John Wayne, Pedro Armendariz, and Harry Carey, Jr. X SPNG 4-6-0 #9 3:10 to Yuma 1957 Glenn Ford and Van Heflin on the Patagonia branch at Elgin, AZ 5 Against the House 1955 Kim Novak and Guy Madison Alco PAs on #27; Alco PAs and #101 at Reno Abba in Concert 1979 Abba, music group Part 1 on Youtube; at 3:13 mark has SP freight train Act of Violence 1948 Van Heflin and Robert Ryan Passenger train scene filmed at depot at Glendale, CA Adventures of Superman 1952-1958 George Reeves Opening credits are of the 1937 Daylight After the Thin Man 1936 William Powell and Myrna Loy Opens with view of Sunset drumhead,Third and Townsend depot in San Francisco, SP 4-6-2 #2483 Again Pioneers 1950 Regis Toomey Minute 32-36, brief views of PFE reefers and PE double-track over Cahuenga Pass Alibi Ike 1935 Joe E. Brown and Olivia de Haviland Los Angeles Central Station and equipment there Alibi Mark 1937 Floyd Gibbons Freight train Always for Pleasure 1978 documentary about Mardi Gras in New Orleans opening shot shows freight train with SP freight cars, mostly hopper cars Americano, The 1955 Glenn Ford probably Chatsworth depot; 4-10-2 steam locomotive pulls a train of PFE reefers Annie Oakley 1954-1957 Gail Davis X Annie and the Cinder Trail: SPNG 9 and freight train, a lot of transfer trestle action Annie Oakley 1954-1957 Gail Davis X Annie and the Desert Adventure: scenes of the SPNG depot area at Keeler