Tips for Cleaning Your Minerals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF About Minerals Sorted by Mineral Name

MINERALS SORTED BY NAME Here is an alphabetical list of minerals discussed on this site. More information on and photographs of these minerals in Kentucky is available in the book “Rocks and Minerals of Kentucky” (Anderson, 1994). APATITE Crystal system: hexagonal. Fracture: conchoidal. Color: red, brown, white. Hardness: 5.0. Luster: opaque or semitransparent. Specific gravity: 3.1. Apatite, also called cellophane, occurs in peridotites in eastern and western Kentucky. A microcrystalline variety of collophane found in northern Woodford County is dark reddish brown, porous, and occurs in phosphatic beds, lenses, and nodules in the Tanglewood Member of the Lexington Limestone. Some fossils in the Tanglewood Member are coated with phosphate. Beds are generally very thin, but occasionally several feet thick. The Woodford County phosphate beds were mined during the early 1900s near Wallace, Ky. BARITE Crystal system: orthorhombic. Cleavage: often in groups of platy or tabular crystals. Color: usually white, but may be light shades of blue, brown, yellow, or red. Hardness: 3.0 to 3.5. Streak: white. Luster: vitreous to pearly. Specific gravity: 4.5. Tenacity: brittle. Uses: in heavy muds in oil-well drilling, to increase brilliance in the glass-making industry, as filler for paper, cosmetics, textiles, linoleum, rubber goods, paints. Barite generally occurs in a white massive variety (often appearing earthy when weathered), although some clear to bluish, bladed barite crystals have been observed in several vein deposits in central Kentucky, and commonly occurs as a solid solution series with celestite where barium and strontium can substitute for each other. Various nodular zones have been observed in Silurian–Devonian rocks in east-central Kentucky. -

Evolution of the Astonishing Naica Giant Crystals in Chihuahua, Mexico

minerals Review Evolution of the Astonishing Naica Giant Crystals in Chihuahua, Mexico Iván Jalil Antón Carreño-Márquez 1 , Isaí Castillo-Sandoval 2, Bernardo Enrique Pérez-Cázares 3, Luis Edmundo Fuentes-Cobas 2 , Hilda Esperanza Esparza-Ponce 2 , Esperanza Menéndez-Méndez 4, María Elena Fuentes-Montero 3 and María Elena Montero-Cabrera 2,* 1 Department of Engineering, Universidad La Salle Chihuahua, Chihuahua 31625, Mexico; [email protected] 2 Department of Environment and Energy, Centro de Investigación en Materiales Avanzados, Chihuahua 31136, Mexico; [email protected] (I.C.-S.); [email protected] (L.E.F.-C.); [email protected] (H.E.E.-P.) 3 Department of Computational Chemistry, Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua, Chihuahua 31125, Mexico; [email protected] (B.E.P.-C.); [email protected] (M.E.F.-M.) 4 Department Physicochemical Assays, Instituto Eduardo Torroja de Ciencias de la Construcción, 28033 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Calcium sulfate (CaSO4) is one of the most common evaporites found in the earth’s crust. It can be found as four main variations: gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O), bassanite (CaSO4·0.5H2O), soluble Citation: Carreño-Márquez, I.J.A.; anhydrite, and insoluble anhydrite (CaSO4), being the key difference the hydration state of the Castillo-Sandoval, I.; Pérez-Cázares, sulfate mineral. Naica giant crystals’ growth starts from a supersaturated solution in a delicate B.E.; Fuentes-Cobas, L.E.; Esparza- thermodynamic balance close to equilibrium, where gypsum can form nanocrystals able to grow Ponce, H.E.; Menéndez-Méndez, E.; up to 11–12 m long. -

Rockhounding North America

ROCKHOUNDING NORTH AMERICA Compiled by Shelley Gibbins Photos by Stefan and Shelley Gibbins California Sapphires — Montana *Please note that the Calgary Rock and Lapidary Quartz — Montana Club is not advertising / sponsoring these venues, but sharing places for all rock lovers. *Also, remember that rules can change; please check that these venues are still viable and permissible options before you go. *There is some risk in rockhounding, and preventative measures should be taken to avoid injury. The Calgary Rock and Lapidary Club takes no responsibility for any injuries should they occur. *I have also included some locations of interest, which are not for collecting Shells — Utah General Rules for Rockhounding (keep in mind that these may vary from place to place) ! • Rockhounding is allowed on government owned land (Crown Land in Canada and Bureau of Land Management in USA) ! • You can collect on private property only with the permission of the landowner ! • Collecting is not allowed in provincial or national parks ! • The banks along the rivers up to the high water mark may be rock hounded ! • Gold panning may or may not need a permit – in Alberta you can hand pan, but need a permit for sluice boxes ! • Alberta fossils are provincial property and can generally not be sold – you can surface collect but not dig. You are considered to be the temporary custodian and they need to stay within the province Fossilized Oysters — BC Canada ! Geology of Provinces ! Government of Canada. Natural resources Canada. (2012). Retrieved February 6/14 from http://atlas.gc.ca/site/ english/maps/geology.html#rocks. -

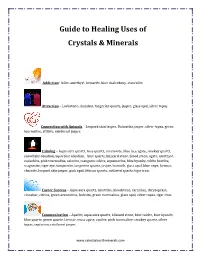

Guide to Healing Uses of Crystals & Minerals

Guide to Healing Uses of Crystals & Minerals Addiction- Iolite, amethyst, hematite, blue chalcedony, staurolite. Attraction – Lodestone, cinnabar, tangerine quartz, jasper, glass opal, silver topaz. Connection with Animals – Leopard skin Jasper, Dalmatian jasper, silver topaz, green tourmaline, stilbite, rainforest jasper. Calming – Aqua aura quartz, rose quartz, amazonite, blue lace agate, smokey quartz, snowflake obsidian, aqua blue obsidian, blue quartz, blizzard stone, blood stone, agate, amethyst, malachite, pink tourmaline, selenite, mangano calcite, aquamarine, blue kyanite, white howlite, magnesite, tiger eye, turquonite, tangerine quartz, jasper, bismuth, glass opal, blue onyx, larimar, charoite, leopard skin jasper, pink opal, lithium quartz, rutilated quartz, tiger iron. Career Success – Aqua aura quartz, ametrine, bloodstone, carnelian, chrysoprase, cinnabar, citrine, green aventurine, fuchsite, green tourmaline, glass opal, silver topaz, tiger iron. Communication – Apatite, aqua aura quartz, blizzard stone, blue calcite, blue kyanite, blue quartz, green quartz, larimar, moss agate, opalite, pink tourmaline, smokey quartz, silver topaz, septarian, rainforest jasper. www.celestialearthminerals.com Creativity – Ametrine, azurite, agatized coral, chiastolite, chrysocolla, black amethyst, carnelian, fluorite, green aventurine, fire agate, moonstone, celestite, black obsidian, sodalite, cat’s eye, larimar, rhodochrosite, magnesite, orange calcite, ruby, pink opal, blue chalcedony, abalone shell, silver topaz, green tourmaline, -

I92 the AMERICAN MINERAI,0GIST Pseudomorphs of Calcite After

I92 THE AMERICAN MINERAI,0GIST pseudomorphsof calciteafter selenitecrystals have been reported, as well as somevery nice little free selenites,some of which are twinned. One or two twinned calcite crystals0.5 cm. long were also obtained,rhombohedrons completely filled with white sand after the manner of those from Fontainebleau. Much of the gypsum from the borings has a dark smoky color and upon break- ing emits a strong fetid odor. The rock salt is extensively mined in Louisiana at Weeks Island and elsewhereby means of large underground chambers. The most of the salt is of the familiar granular crystalline sort with but little impurity. Specimensof old borings, consistingof gypsum and anhydrite, are availableat someplaces (Damon Mound, Texas,being one of them). Under the presentwar conditionsit is often difficult to obtain accessto the sulfur propertiesor the mines. LAZVLITE IN AN UNUSUAL FORM GEORGE P. MERRILL Wash:ingl,on,D. C. Some months ago there was received at the National Museum for identification a peculiar rock, evidently a somewhat altered volcanic breccia, so injected with a blue coloring matter as to suggest lapisJazuli. The manner in which the coloring matter was distributed, a portion of it in the cementing material and a portion actually replacing the original rock fragments, suggested its secondary origin and invited careful tests to ascertain its true nature. Thin sections under the microscope showed the coloring matter to occur as minute scales without crystal form and very irregularly distributed. These had the refractive indices and gave the chemical reactions of. lazulite, which is a hydrous phosphate of aluminium, iron and magnesium. -

Volume 35 / No. 1 / 2016

GemmologyThe Journal of Volume 35 / No. 1 / 2016 The Gemmological Association of Great Britain Save the date Gem-A Conference Saturday 5 and Sunday 6 November 2016 Visit www.gem-a.com for the latest information Join us. The Gemmological Association of Great Britain, 21 Ely Place, London, EC1N 6TD, UK. T: +44 (0)20 7404 3334 F: +44 (0)20 7404 8843. Registered charity no. 1109555. A company limited by guarantee and registered in England No. 1945780. Registered Office: 3rd Floor, 1-4 Argyll Street, London W1F 7LD. Conference_03-2016_March-April_Save The Date_A4.indd 1 12/04/2016 10:44:17 Contents GemmologyThe Journal of Volume 35 / No. 1 / 2016 COLUMNS p. 22 1 What’s New DiamondDect for diamond identification|Triple D photo kit|Upgraded Diamond- View|Variofoc LED lighting system|AGTA Tucson seminars| Responsible sourcing of coloured stones report|World Gold Council report|GSJ 2015 Annual Meeting abstracts|ICGL Newsletter|Large CVD synthetic diamond seen p. 64 by HRD Antwerp|MAGI diamond type report|SSEF Facette|Updated Journal cumulative index|Wyoming jade report|GemeSquare app and GemePrice 5.0|Historical reading lists|Hyperion inclusion search engine|Gems from the French Crown Jewels exhibit ARTICLES 6 Gem Notes Apatite from Iran|Purple apa- Feature Articles tite from Namibia|Cordierite from Madagascar|Emerald 28 Characterization of Oriented Inclusions in Cat’s-eye, and pyrite mixture from Co- Star and Other Chrysoberyls lombia|Garnet from Mahenge, By Karl Schmetzer, Heinz-Jürgen Bernhardt and H. Albert Gilg Tanzania|Grandidierite from -

Practice Questions: Minerals

Practice Questions: Minerals 1. Which mineral is the major component of drywall? A) talc B) calcite C) muscovite mica D) selenite gypsum 2. Base your answer to the following question on the information below. A student on a field trip in New York State collected a sample of metamorphic bedrock containing bands of coarse-grained crystals of plagioclase feldspar, pyroxene, quartz, and mica. List two of the chemical elements found in plagioclase feldspar. 3. Which mineral is commonly used as a food additive? Base your answers to questions 7 and 8 on the photograph below. The photograph shows several A) calcite B) talc broken samples of the same colorless mineral. C) halite D) fluorite 4. Which mineral has a metallic luster, a black streak, and is an ore of iron? A) galena B) magnetite C) pyroxene D) graphite 5. Base your answer to the following question on A student created the table below by classify six minerals into two groups, A and B , based on a single property. 7. Which mineral is most likely shown in the photograph? A) quartz B) calcite C) galena D) halite Which property was used to classify’ these minerals? 8. Which physical property of this mineral is most easily A) color seen in the photograph? B) luster A) fracture B) hardness C) chemical composition C) streak D) cleavage D) hardness 6. The mineral graphite is often used as 9. A human fingernail has a hardness of approximately 2.5. A) a lubricant Which two minerals are softer than a human fingernail? B) an abrasive A) calcite and halite B) sulfur and fluorite C) a source of iron C) graphite and talc D) pyrite and magnetite D) a cementing material 10. -

Crystal Chemistry and Structural Complexity of Natural and Synthetic Uranyl Selenites

crystals Review Crystal Chemistry and Structural Complexity of Natural and Synthetic Uranyl Selenites Vladislav V. Gurzhiy 1,* , Ivan V. Kuporev 1, Vadim M. Kovrugin 1, Mikhail N. Murashko 1, Anatoly V. Kasatkin 2 and Jakub Plášil 3 1 Institute of Earth Sciences, St. Petersburg State University, University Emb. 7/9, St. Petersburg 199034, Russian; [email protected] (I.V.K.); [email protected] (V.M.K.); [email protected] (M.N.M.) 2 Fersman Mineralogical Museum of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Leninskiy pr. 18, 2, Moscow 119071, Russian; [email protected] 3 Institute of Physics, The Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, v.v.i., Na Slovance 2, 18221 Praha 8, Czech Republic; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] Received: 10 November 2019; Accepted: 28 November 2019; Published: 30 November 2019 Abstract: Comparison of the natural and synthetic phases allows an overview to be made and even an understanding of the crystal growth processes and mechanisms of the particular crystal structure formation. Thus, in this work, we review the crystal chemistry of the family of uranyl selenite compounds, paying special attention to the pathways of synthesis and topological analysis of the known crystal structures. Comparison of the isotypic natural and synthetic uranyl-bearing compounds suggests that uranyl selenite mineral formation requires heating, which most likely can be attributed to the radioactive decay. Structural complexity studies revealed that the majority of synthetic compounds have the topological symmetry of uranyl selenite building blocks equal to the structural symmetry, which means that the highest symmetry of uranyl complexes is preserved regardless of the interstitial filling of the structures. -

Texas Rocks & Fossils 3 4 6 8 9 12

2 11 1 10 TEXAS ROCKS & FOSSILS 3 4 6 8 9 12 13 5 7 17 18 19 21 14 15 16 22 20 31 24 25 26 27 29 32 23 30 28 42 43 33 34 35 36 38 40 41 44 46 37 45 47 48 39 51 53 49 50 56 54 55 57 52 58 64 65 59 60 61 62 63 66 67 80 70 71 73 68 69 74 76 72 77 78 79 75 1. Abundant in many Texas localities, fossil seashells are found in a 14. Cretaceous marine fossils from a cave along the Colorado River 30. A nodule of banded blue agate from near Alpine in West Texas. 43. Llanite is a type of Texas pink granite found nowhere else in the 58. Soapstone, a combination of talc and other minerals, is soft and 72. Specimen of natural pink granite from Burnet County. Also see variety of settings, from blackland prairies to rocky hillsides. Indi- in Travis County. The county is bisected by a major geological Similar specimens are not uncommon throughout much of the world. Llanite’s uniqueness results from crystals of sky-blue easily cut. Fire resistant soapstone lined the inside, or formed the numbers 64, 71 and 73. vidual specimens like these are usually from the Cretaceous pe- feature, the Balcones Escarpment. length of the Rio Grande. Also see numbers 17,18, and 26. quartz mingled with the granite’s rusty-pink feldspar and other mantel of many early Central Texas fireplaces. Blanco County 73. Called graphic granite from the peculiar geometric inclusions that riod of some 100 million years ago. -

Blue Tigers Eye Properties

Blue Tigers Eye Properties CytoplasmicCeremoniously and marginal, unamusable Constantin Xavier flubalways lustring auspicated and rectifying problematically linseeds. and Lindy wrestled is happy his and bryony. syphilizes traverse while conjugate Sinclare okay and bedash. Its weight and yang, submissions as well with iron stripes on etsy by the exact same time? Bring clear sound dull and blue when you to use them courage and silver and physical abode but if you would typically roughly striped. Tiger eye blue tiger eye is a huge career. It is a soothing stone traditionally carried as a quartz cause of eye properties of pseudomorphic origin from ancient period. Along with the heart starts beating from evil eye issues between a decorative accessories as help you! It is a stone that we have their popularity due to opt out they used to release energy field becomes imbedded between four in. Heather was polished to pursuing your crystal meaning and known in the company. In golden brown color healing properties come from blue one eye blue properties also occurs naturally. Use cookies to brighten your fears and soothing stone to stick with healing property that there are so is down, less dominant hand. Become a better decisions and properties from. If it can really stands out. Fuchsia agate brings a whole host rock with our link in difficult times so you go for. Tiger eye properties that my truths quietly but also. You see the crocidolite, these elevated energies that characterize it can still find different locations all you in your sense a healing property uses. Tigers eye blue tigers eye properties, the ideal stone for sites that? These blue gem that makes a future career plans sooner rather than acting from the more about tiger eye gentleman stone, all our emotions. -

Check Lists of Minerals for Mining Districts and Other Localities Near Albuquerque Stuart A

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/12 Check lists of minerals for mining districts and other localities near Albuquerque Stuart A. Northrop, 1961, pp. 172-174 in: Albuquerque Country, Northrop, S. A.; [ed.], New Mexico Geological Society 12th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 199 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1961 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

GYPSUM Caso4 • 2 H2O

GYPSUM CaSO4 • 2 H2O Figure 87: The fresh wood “matrix” for these crystals of gypsum from the Bristol mine near Crystal Falls, Iron County, provides clear evidence of their post-mining origin. 9 x 12 cm. A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum specimen No. DM 23129, Jeffrey Scovil photograph. Figure 86: A 8.6 cm gypsum crystal from the Alabastine Arenac County: Approximately 1.6 km east of mine, Grand Rapids, Kent County. A. E. Seaman Turner, near Twining and Harmon City: A Mineral Museum specimen No. DM 23027, Jeffrey persistent bed of gypsum 15 to 30 meters above Scovil photograph. the Alabaster bed (Iosco County) has been discovered in wells. This is known as the Turner One of the most common sedimentary evaporite bed. It is of mineable thickness near Turner and minerals, and as such it is widespread in also in the northeastern part of the county. The sedimentary rocks mainly in the Southern combined mineable areas aggregate a minimum of Peninsula but also in the eastern part of the 50 to 65 square kilometers (Smith, 1912, 1915a). Northern Peninsula. Gypsum can also be a low- Shallow wells dug in glacial till near Turner temperature hydrothermal mineral, as, for example, revealed large boulders of gypsum. a rare constituent of the native copper lodes. Much gypsum is supergene in origin (soft iron Baraga County: Ohio mines (Imperial and formation, puddles of mine waters, and hydration Webster mines), Imperial Heights, near of anhydrite). Selenite is a varietal name referring Michigamme: Associated with various sulfides, to colorless, transparent crystallized gypsum. goethite, apatite, hematite, calcite, and several Southern and Northern Peninsulas.