Atypical, Yet Not Infrequent, Infections with Neisseria Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Nh Dhhs Health Alert

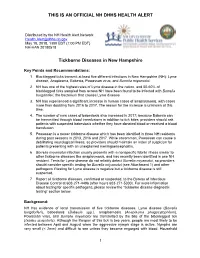

THIS IS AN OFFICIAL NH DHHS HEALTH ALERT Distributed by the NH Health Alert Network [email protected] May 18, 2018, 1300 EDT (1:00 PM EDT) NH-HAN 20180518 Tickborne Diseases in New Hampshire Key Points and Recommendations: 1. Blacklegged ticks transmit at least five different infections in New Hampshire (NH): Lyme disease, Anaplasma, Babesia, Powassan virus, and Borrelia miyamotoi. 2. NH has one of the highest rates of Lyme disease in the nation, and 50-60% of blacklegged ticks sampled from across NH have been found to be infected with Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. 3. NH has experienced a significant increase in human cases of anaplasmosis, with cases more than doubling from 2016 to 2017. The reason for the increase is unknown at this time. 4. The number of new cases of babesiosis also increased in 2017; because Babesia can be transmitted through blood transfusions in addition to tick bites, providers should ask patients with suspected babesiosis whether they have donated blood or received a blood transfusion. 5. Powassan is a newer tickborne disease which has been identified in three NH residents during past seasons in 2013, 2016 and 2017. While uncommon, Powassan can cause a debilitating neurological illness, so providers should maintain an index of suspicion for patients presenting with an unexplained meningoencephalitis. 6. Borrelia miyamotoi infection usually presents with a nonspecific febrile illness similar to other tickborne diseases like anaplasmosis, and has recently been identified in one NH resident. Tests for Lyme disease do not reliably detect Borrelia miyamotoi, so providers should consider specific testing for Borrelia miyamotoi (see Attachment 1) and other pathogens if testing for Lyme disease is negative but a tickborne disease is still suspected. -

Melioidosis: a Clinical Model for Gram-Negative Sepsis

J. Med. Microbiol. Ð Vol. 50 2001), 657±658 # 2001 The Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland ISSN 0022-2615 EDITORIAL Melioidosis: a clinical model for gram-negative sepsis The recently published study of recombinant human clinical sepsis model over the current heterogeneous activated protein C drotrecogin-á, Eli Lilly, Indiana- clinical trials. Our knowledge of melioidosis and its polis, IN, USA) in severe sepsis makes welcome causative organism, Burkholderia formerly Pseudomo- reading. At last a clinical trial of an augmentative nas) pseudomallei, has expanded considerably over the therapy in severe sepsis has managed to show a last 15 years. Melioidosis was originally described in mortality bene®t from the trial agent [1]. Most studies Myanmar then Burma) in 1911 and came to of augmentative treatments in serious sepsis have failed prominence during the Vietnam con¯ict, when French to show clear bene®t. Sepsis studies commonly involve and American soldiers became infected. It has been a syndrome caused by a myriad of organisms, occurring described in most countries of south-east Asia, in a very heterogeneous group of patients, who may be including the Peoples Republic of China and the Lao enrolled in one of several centres. This introduces PDR [5], but Thailand has the greatest reported disease multiple confounding factors. Agood model for clinical burden [6]. It is also endemic to northern Australia [7]. sepsis studies would ideally cause disease in a relatively Understanding of the epidemiology of the disease has homogeneous population, be acquired in a community been improved by the demonstration of two pheno- setting, present in large numbers to a single institution, typically similar but genetically distinct biotypes in the be caused by a single organism, and ordinarily result in environment [8], only one of which appears to be a substantial mortality rate. -

Kellie ID Emergencies.Pptx

4/24/11 ID Alert! recognizing rapidly fatal infections Susan M. Kellie, MD, MPH Professor of Medicine Division of Infectious Diseases, UNMSOM Hospital Epidemiologist UNMHSC and NMVAHCS Fever and…. Rash and altered mental status Rash Muscle pain Lymphadenopathy Hypotension Shortness of breath Recent travel Abdominal pain and diarrhea Case 1. The cross-country trucker A 30 year-old trucker driving from Oklahoma to California is hospitalized in Deming with fever and headache He is treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, but deteriorates with obtundation, low platelet count, and a centrifugal petechial rash and is transferred to UNMH 1 4/24/11 What is your diagnosis? What is the differential diagnosis of fever and headache with petechial rash? (in the US) Tickborne rickettsioses ◦ RMSF Bacteria ◦ Neisseria meningitidis Key diagnosis in this case: “doxycycline deficiency” Key vector-borne rickettsioses treated with doxycycline: RMSF-case-fatality 5-10% ◦ Fever, nausea, vomiting, myalgia, anorexia and headache ◦ Maculopapular rash progresses to petechial after 2-4 days of fever ◦ Occasionally without rash Human granulocytotropic anaplasmosis (HGA): case-fatality<1% Human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis (HME): case fatality 2-3% 2 4/24/11 Lab clues in rickettsioses The total white blood cell (WBC) count is typicallynormal in patients with RMSF, but increased numbers of immature bands are generally observed. Thrombocytopenia, mild elevations in hepatic transaminases, and hyponatremia might be observed with RMSF whereas leukopenia -

Avoidance of Mechanisms of Innate Immune Response by Neisseria Gonorrhoeae

ADVANCEMENTS OF MICROBIOLOGY – POSTĘPY MIKROBIOLOGII 2019, 58, 4, 367–373 DOI: 10.21307/PM–2019.58.4.367 AVOIDANCE OF MECHANISMS OF INNATE IMMUNE RESPONSE BY NEISSERIA GONORRHOEAE Jagoda Płaczkiewicz* Department of Virology, Institute of Microbiology, Faculty of Biology, University of Warsaw Submitted in July, accepted in October 2019 Abstract: Neisseria gonorrhoeae (gonococcus) is a Gram-negative bacteria and an etiological agent of the sexually transmitted disease – gonorrhea. N. gonorrhoeae possesses many mechanism to evade the innate immune response of the human host. Most are related to serum resistance and avoidance of complement killing. However the clinical symptoms of gonorrhea are correlated with a significant pres- ence of neutrophils, whose response is also insufficient and modulated by gonococci. 1. Introduction. 2. Adherence ability. 3. Serum resistance and complement system. 4. Neutrophils. 4.1. Phagocytosis. 4.1.1. Oxygen- dependent intracellular killing. 4.1.2. Oxygen-independent intracellular killing. 4.2. Neutrophil extracellular traps. 4.3. Degranulation. 4.4. Apoptosis. 5. Summary UNIKANIE MECHANIZMÓW WRODZONEJ ODPOWIEDZI IMMUNOLOGICZNEJ PRZEZ NEISSERIA GONORRHOEAE Streszczenie: Neisseria gonorrhoeae (gonokok) to Gram-ujemna dwoinka będąca czynnikiem etiologicznym choroby przenoszonej drogą płciową – rzeżączki. N. gonorrhoeae posiada liczne mechanizmy umożliwiające jej unikanie wrodzonej odpowiedzi immunologicznej gospodarza. Większość z nich związana jest ze zdolnością gonokoków do manipulowania układem dopełniacza gospodarza oraz odpor- nością tej bakterii na surowicę. Jednakże symptomy infekcji N. gonorrhoeae wynikają między innymi z obecności licznych neutrofili, których aktywność jest modulowana przez gonokoki. 1. Wprowadzenie. 2. Zdolność adherencji. 3. Surowica i układ dopełniacza. 4. Neutrofile. 4.1. Fagocytoza. 4.1.1. Wewnątrzkomórkowe zabijanie zależne od tlenu. 4.1.2. -

Pearls: Infectious Diseases

Pearls: Infectious Diseases Karen L. Roos, M.D.1 ABSTRACT Neurologists have a great deal of knowledge of the classic signs of central nervous system infectious diseases. After years of taking care of patients with infectious diseases, several symptoms, signs, and cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities have been identified that are helpful time and time again in determining the etiological agent. These lessons, learned at the bedside, are reviewed in this article. KEYWORDS: Herpes simplex virus, Lyme disease, meningitis, viral encephalitis CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS does not have an altered level of consciousness, sei- zures, or focal neurologic deficits. Although the ‘‘classic triad’’ of bacterial meningitis is The rash of a viral exanthema typically involves the fever, headache, and nuchal rigidity, vomiting is a face and chest first then spreads to the arms and legs. common early symptom. Suspect bacterial meningitis This can be an important clue in the patient with in the patient with fever, headache, lethargy, and headache, fever, and stiff neck that the meningitis is vomiting (without diarrhea). Patients may also com- due to echovirus or coxsackievirus. plain of photophobia. An altered level of conscious- Suspect tuberculous meningitis in the patient with ness that begins with lethargy and progresses to stupor either several weeks of headache, fever, and night during the emergency evaluation of the patient is sweats or a fulminant presentation with fever, altered characteristic of bacterial meningitis. mental status, and focal neurologic deficits. Fever (temperature 388C[100.48F]) is present in An Ixodes tick must be attached to the skin for at least 84% of adults with bacterial meningitis and in 80 to 24 hours to transmit infection with the spirochete 1–3 94% of children with bacterial meningitis. -

July 26, 2017 Bruker Daltonik Gmbh Mr. David Cromwick Director Of

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Food and Drug Administration 10903 New Hampshire Avenue Document Control Center – WO66-G609 Silver Spring, MD 20993-0002 July 26, 2017 Bruker Daltonik GmbH Mr. David Cromwick Director of Quality 40 Manning Rd Billerica, MA 01821 US Re: K163536 Trade/Device Name: MALDI Biotyper CA (MBT-CA) System, MBT smart CA System Regulation Number: 21 CFR 866.3361 Regulation Name: Mass spectrometer system for clinical use for the identification of microorganisms Regulatory Class: II Product Code: PEX Dated: December 16, 2016 Received: December 16, 2016 Dear Mr. Cromwick: We have reviewed your Section 510(k) premarket notification of intent to market the device referenced above and have determined the device is substantially equivalent (for the indications for use stated in the enclosure) to legally marketed predicate devices marketed in interstate commerce prior to May 28, 1976, the enactment date of the Medical Device Amendments, or to devices that have been reclassified in accordance with the provisions of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (Act) that do not require approval of a premarket approval application (PMA). You may, therefore, market the device, subject to the general controls provisions of the Act. The general controls provisions of the Act include requirements for annual registration, listing of devices, good manufacturing practice, labeling, and prohibitions against misbranding and adulteration. Please note: CDRH does not evaluate information related to contract liability warranties. We remind you, however, that device labeling must be truthful and not misleading. If your device is classified (see above) into either class II (Special Controls) or class III (PMA), it may be subject to additional controls. -

Proctitis Associated with Neisseria Cinerea Misidentified As Neisseria Gonorrhoeae in a Child JOHN H

JOURNAL OF CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY, Apr. 1985, p. 575-577 Vol. 21, No. 4 0095-1137/85/040575-03$02.00/0 Copyright C 1985, American Society for Microbiology Proctitis Associated with Neisseria cinerea Misidentified as Neisseria gonorrhoeae in a Child JOHN H. DOSSETT,' PETER C. APPELBAUM,2* JOAN S. KNAPP,3 AND PATRICIA A. TOTTEN3 Departments ofPediatrics (Infectious Diseases)' and Pathology (Clinical Microbiology),2 Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, Pennsylvania 17033, and Neisseria Reference Laboratory and Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 981953 Received 21 September 1984/Accepted 13 December 1984 An 8-year-old boy developed proctitis. Rectal swabs yielded a Neisseria sp. that was repeatedly identified by API (Analytab Products, Plainview, N.Y.), Minitek (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.), and Bactec (Johnston Laboratories, Towson, Md.) methods as Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Subsequent testing in a reference laboratory yielded an identification of Neisseria cinerea. It is suggested that identification of a Neisseria sp. isolated from genital or rectal sites in a child be confirmed by additional serological, growth, and antibiotic susceptibility tests and, if necessary, by a reference laboratory. The implications of such misidenti- fications are discussed. Gonococcal proctitis in children is usually considered to rectal scrubs. The child and his parents underwent extensive be sexually transmitted, just as it is in adults. Moreover, questioning in an effort to identify a source of infection. No gonorrhea in young boys is generally the result of homosex- clues were found. Both parents had negative examinations ual contact with an adult male. We herein report the case of and negative cultures. The patient's condition gradually a child with prolonged proctitis and perianal inflammation improved, and by 20 July his rectum and perirectum ap- from whom Neisseria sp. -

Neisseria Infection of Rhesus Macaques As a Model to Study Colonization, Transmission, Persistence, and Horizontal Gene Transfer

Neisseria infection of rhesus macaques as a model to study colonization, transmission, persistence, and horizontal gene transfer Nathan J. Weyanda,b,1, Anne M. Wertheimerc,d,e, Theodore R. Hobbsf,g, Jennifer L. Siskoa,b, Nyiawung A. Takua,b, Lindsay D. Gregstona,b, Susan Claryh, Dustin L. Higashia,b, Nicolas Biaisi,2, Lewis M. Browni,j, Shannon L. Planerg,k, Alfred W. Legasseg,k, Michael K. Axthelmg,k,l, Scott W. Wongg,h,l, and Magdalene Soa,b aBIO5 Institute and bDepartment of Immunobiology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721; cArizona Center on Aging, dDepartment of Medicine and eDivision of Geriatrics General Internal and Palliative Medicine, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, 85719; fDivision of Animal Resources, kDivision of Pathobiology and Immunology, gOregon National Primate Research Center, and lVaccine and Gene Therapy Institute, Oregon Health and Science University, Beaverton, OR 97006; hDepartment of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology, L220, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR 97239; and iDepartment of Biological Sciences and jQuantitative Proteomics Center, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027 Edited by Rino Rappuoli, Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics, Siena, Italy, and approved January 10, 2013 (received for review October 9, 2012) The strict tropism of many pathogens for man hampers the de- may be possible to develop a model for studying Neisseria–host velopment of animal models that recapitulate important microbe– interactions in which there are no host-restriction barriers to host interactions. We developed a rhesus macaque model for study- overcome. ing Neisseria–host interactions using Neisseria species indigenous to The rhesus macaque (RM) has ∼93% DNA sequence identity the animal. -

Potential of Metabolomics to Reveal Burkholderia Cepacia Complex Pathogenesis and Antibiotic Resistance

MINI REVIEW published: 13 July 2015 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00668 Potential of metabolomics to reveal Burkholderia cepacia complex pathogenesis and antibiotic resistance Nusrat S. Shommu 1, Hans J. Vogel 1 and Douglas G. Storey 2* 1 Biochemistry Research Group, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 2 Microbiology Research Group, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada The Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc) is a collection of closely related, genetically distinct, ecologically diverse species known to cause life-threatening infections in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients. By virtue of a flexible genomic structure and diverse metabolic activity, Bcc bacteria employ a wide array of virulence factors for pathogenesis Edited by: in CF patients and have developed resistance to most of the commonly used Steve Lindemann, Pacific Northwest National antibiotics. However, the mechanism of pathogenesis and antibiotic resistance is still Laboratory, USA not fully understood. This mini review discusses the established and potential virulence Reviewed by: determinants of Bcc and some of the contemporary strategies including transcriptomics Joanna Goldberg, Emory University School and proteomics used to identify these traits. We also propose the application of metabolic of Medicine, USA profiling, a cost-effective modern-day approach to achieve new insights. Tom Metz, Pacific Northwest National Keywords: Burkholderia cepacia complex, virulence, antibiotic resistance, metabolomics, cystic fibrosis Laboratory, USA *Correspondence: Burkholderia cepacia Complex in Cystic Fibrosis Douglas G. Storey, Microbiology Research Group, Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc) is a group of at least 17 Gram-negative b-proteobacteria that Department of Biological are phenotypically related but genetically discrete (Mahenthiralingam et al., 2005; Vanlaere et al., Sciences, University of Calgary, 2008, 2009). -

African Meningitis Belt

WHO/EMC/BAC/98.3 Control of epidemic meningococcal disease. WHO practical guidelines. 2nd edition World Health Organization Emerging and other Communicable Diseases, Surveillance and Control This document has been downloaded from the WHO/EMC Web site. The original cover pages and lists of participants are not included. See http://www.who.int/emc for more information. © World Health Organization This document is not a formal publication of the World Health Organization (WHO), and all rights are reserved by the Organization. The document may, however, be freely reviewed, abstracted, reproduced and translated, in part or in whole, but not for sale nor for use in conjunction with commercial purposes. The views expressed in documents by named authors are solely the responsibility of those authors. The mention of specific companies or specific manufacturers' products does no imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................................................... i PREFACE ..................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................... 1 1. MAGNITUDE OF THE PROBLEM ........................................................3 1.1 REVIEW OF EPIDEMICS SINCE THE 1970S .......................................................................................... 3 Geographical distribution -

Forensic Microbiology Reveals That Neisseria Animaloris Infections In

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Forensic microbiology reveals that Neisseria animaloris infections in harbour porpoises follow traumatic Received: 14 February 2019 Accepted: 20 September 2019 injuries by grey seals Published: xx xx xxxx Geofrey Foster 1, Adrian M. Whatmore2, Mark P. Dagleish3, Henry Malnick4, Maarten J. Gilbert5, Lineke Begeman6, Shaheed K. Macgregor7, Nicholas J. Davison1, Hendrik Jan Roest8, Paul Jepson7, Fiona Howie9, Jakub Muchowski2, Andrew C. Brownlow1, Jaap A. Wagenaar5,8, Marja J. L. Kik10, Rob Deaville7, Mariel T. I. ten Doeschate1, Jason Barley1,11, Laura Hunter1 & Lonneke L. IJsseldijk 10 Neisseria animaloris is considered to be a commensal of the canine and feline oral cavities. It is able to cause systemic infections in animals as well as humans, usually after a biting trauma has occurred. We recovered N. animaloris from chronically infamed bite wounds on pectoral fns and tailstocks, from lungs and other internal organs of eight harbour porpoises. Gross and histopathological evidence suggest that fatal disseminated N. animaloris infections had occurred due to traumatic injury from grey seals. We therefore conclude that these porpoises survived a grey seal predatory attack, with the bite lesions representing the subsequent portal of entry for bacteria to infect the animals causing abscesses in multiple tissues, and eventually death. We demonstrate that forensic microbiology provides a useful tool for linking a perpetrator to its victim. Moreover, N. animaloris should be added to the list of potential zoonotic bacteria following interactions with seals, as the fnding of systemic transfer to the lungs and other tissues of the harbour porpoises may suggest a potential to do likewise in humans. -

Neisseria Gonorrhoeae Infection by Functioning Igm Memory B Cells

Vigorous Response of Human Innate Functioning IgM Memory B Cells upon Infection by Neisseria gonorrhoeae This information is current as Nancy S. Y. So, Mario A. Ostrowski and Scott D. of October 1, 2021. Gray-Owen J Immunol 2012; 188:4008-4022; Prepublished online 16 March 2012; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100718 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/188/8/4008 Downloaded from Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2012/03/16/jimmunol.110071 Material 8.DC1 http://www.jimmunol.org/ References This article cites 69 articles, 32 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/188/8/4008.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists by guest on October 1, 2021 • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2012 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. The Journal of Immunology Vigorous Response of Human Innate Functioning IgM Memory B Cells upon Infection by Neisseria gonorrhoeae Nancy S.