Royal Institute of Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Difference Between Higher and Lower Flap Setting Configurations May Seem Small, but at Today's Fuel Prices the Savings Can Be Substantial

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN HIGHER AND LOWER FLAP SETTING CONFIGURATIONS MAY SEEM SMALL, BUT AT TODAY'S FUEL PRICES THE SAVINGS CAN BE SUBSTANTIAL. 24 AERO QUARTERLY QTR_04 | 08 Fuel Conservation Strategies: Takeoff and Climb By William Roberson, Senior Safety Pilot, Flight Operations; and James A. Johns, Flight Operations Engineer, Flight Operations Engineering This article is the third in a series exploring fuel conservation strategies. Every takeoff is an opportunity to save fuel. If each takeoff and climb is performed efficiently, an airline can realize significant savings over time. But what constitutes an efficient takeoff? How should a climb be executed for maximum fuel savings? The most efficient flights actually begin long before the airplane is cleared for takeoff. This article discusses strategies for fuel savings But times have clearly changed. Jet fuel prices fuel burn from brake release to a pressure altitude during the takeoff and climb phases of flight. have increased over five times from 1990 to 2008. of 10,000 feet (3,048 meters), assuming an accel Subse quent articles in this series will deal with At this time, fuel is about 40 percent of a typical eration altitude of 3,000 feet (914 meters) above the descent, approach, and landing phases of airline’s total operating cost. As a result, airlines ground level (AGL). In all cases, however, the flap flight, as well as auxiliarypowerunit usage are reviewing all phases of flight to determine how setting must be appropriate for the situation to strategies. The first article in this series, “Cost fuel burn savings can be gained in each phase ensure airplane safety. -

Emergency Procedures C172

EMERGENCY PROCEDURES NON CRITICAL ACTION June 2015 1. Maintain aircraft control. Table of Contents 2. Analyze the situation and take proper action. C 172 3.Land as soon as conditions permit NON CRITICAL ACTION PROCEDURES E-2 GROUND OPERATION EMERGENCIES GROUND OPERATION EMERGENCIES E-2 Emergency Engine Shutdown on the Ground Emergency Engine Shutdown on the Ground E-2 1. FUEL SELECTOR -------------------------------- OFF Engine Fire During Start E-2 2. MIXTURE ---------------------------- IDLE CUTOFF TAKEOFF EMERGENCIES E-2 3. IGNITION ------------------------------------------ OFF Abort E-2 4. MASTER SWITCH ------------------------------- OFF IN-FLIGHT EMERGENCIES E-3 Engine Failure Immediately After T/O E-3 Engine Fire during Start Engine Failure In Flt - Forced Landing E-3 If Engine starts Engine Fire During Flight E-4 1. POWER ------------------------------------- 1700 RPM Emergency Descent E-4 2. ENGINE -------------------------------- SHUTDOWN Electrical Fire/High Ammeter E-4 If Engine fails to start Negative Ammeter Reading E-4 1. CRANKING ----------------------------- CONTINUE Smoke and Fume Elimination E-5 2. MIXTURE --------------------------- IDLE CUT-OFF Oil System Malfunction E-4 3 THROTTLE ----------------------------- FULL OPEN Structural Damage or Controllability Check E-5 4. ENGINE -------------------------------- SHUTDOWN Recall E-6 FUEL SELECTOR ------ OFF Lost Procedures E-6 IGNITION SWITCH --- OFF Radio Failure E-7 MASTER SWITCH ----- OFF Diversions E-8 LANDING EMERGENCIES E-9 TAKEOFF EMERGENCIES Landing with flat tire E-9 ABORT E-9 LIGHT SIGNALS 1. THROTTLE -------------------------------------- IDLE 2. BRAKES ----------------------------- AS REQUIRED E-2 E-1 IN-FLIGHT EMERGENCIES Engine Fire During Flight Engine Failure Immediately After Takeoff 1. FUEL SELECTOR --------------------------------------- OFF 1. BEST GLIDE ------------------------------------ ESTABLISH 2. MIXTURE------------------------------------ IDLE CUTOFF 2. FUEL SELECTOR ----------------------------------------- OFF 3. -

Aircraft Performance (R18a2110)

AERONAUTICAL ENGINEERING – MRCET (UGC Autonomous) AIRCRAFT PERFORMANCE (R18A2110) COURSE FILE II B. Tech II Semester (2019-2020) Prepared By Ms. D.SMITHA, Assoc. Prof Department of Aeronautical Engineering MALLA REDDY COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY (Autonomous Institution – UGC, Govt. of India) Affiliated to JNTU, Hyderabad, Approved by AICTE - Accredited by NBA & NAAC – ‘A’ Grade - ISO 9001:2015 Certified) Maisammaguda, Dhulapally (Post Via. Kompally), Secunderabad – 500100, Telangana State, India. AERONAUTICAL ENGINEERING – MRCET (UGC Autonomous) MRCET VISION • To become a model institution in the fields of Engineering, Technology and Management. • To have a perfect synchronization of the ideologies of MRCET with challenging demands of International Pioneering Organizations. MRCET MISSION To establish a pedestal for the integral innovation, team spirit, originality and competence in the students, expose them to face the global challenges and become pioneers of Indian vision of modern society . MRCET QUALITY POLICY. • To pursue continual improvement of teaching learning process of Undergraduate and Post Graduate programs in Engineering & Management vigorously. • To provide state of art infrastructure and expertise to impart the quality education. [II year – II sem ] Page 2 AERONAUTICAL ENGINEERING – MRCET (UGC Autonomous) PROGRAM OUTCOMES (PO’s) Engineering Graduates will be able to: 1. Engineering knowledge: Apply the knowledge of mathematics, science, engineering fundamentals, and an engineering specialization to the solution -

Chapter: 4. Approaches

Chapter 4 Approaches Introduction This chapter discusses general planning and conduct of instrument approaches by pilots operating under Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) Parts 91,121, 125, and 135. The operations specifications (OpSpecs), standard operating procedures (SOPs), and any other FAA- approved documents for each commercial operator are the final authorities for individual authorizations and limitations as they relate to instrument approaches. While coverage of the various authorizations and approach limitations for all operators is beyond the scope of this chapter, an attempt is made to give examples from generic manuals where it is appropriate. 4-1 Approach Planning within the framework of each specific air carrier’s OpSpecs, or Part 91. Depending on speed of the aircraft, availability of weather information, and the complexity of the approach procedure Weather Considerations or special terrain avoidance procedures for the airport of intended landing, the in-flight planning phase of an Weather conditions at the field of intended landing dictate instrument approach can begin as far as 100-200 NM from whether flight crews need to plan for an instrument the destination. Some of the approach planning should approach and, in many cases, determine which approaches be accomplished during preflight. In general, there are can be used, or if an approach can even be attempted. The five steps that most operators incorporate into their flight gathering of weather information should be one of the first standards manuals for the in-flight planning phase of an steps taken during the approach-planning phase. Although instrument approach: there are many possible types of weather information, the primary concerns for approach decision-making are • Gathering weather information, field conditions, windspeed, wind direction, ceiling, visibility, altimeter and Notices to Airmen (NOTAMs) for the airport of setting, temperature, and field conditions. -

4. Lunar Architecture

4. Lunar Architecture 4.1 Summary and Recommendations As defined by the Exploration Systems Architecture Study (ESAS), the lunar architecture is a combination of the lunar “mission mode,” the assignment of functionality to flight elements, and the definition of the activities to be performed on the lunar surface. The trade space for the lunar “mission mode,” or approach to performing the crewed lunar missions, was limited to the cislunar space and Earth-orbital staging locations, the lunar surface activities duration and location, and the lunar abort/return strategies. The lunar mission mode analysis is detailed in Section 4.2, Lunar Mission Mode. Surface activities, including those performed on sortie- and outpost-duration missions, are detailed in Section 4.3, Lunar Surface Activities, along with a discussion of the deployment of the outpost itself. The mission mode analysis was built around a matrix of lunar- and Earth-staging nodes. Lunar-staging locations initially considered included the Earth-Moon L1 libration point, Low Lunar Orbit (LLO), and the lunar surface. Earth-orbital staging locations considered included due-east Low Earth Orbits (LEOs), higher-inclination International Space Station (ISS) orbits, and raised apogee High Earth Orbits (HEOs). Cases that lack staging nodes (i.e., “direct” missions) in space and at Earth were also considered. This study addressed lunar surface duration and location variables (including latitude, longi- tude, and surface stay-time) and made an effort to preserve the option for full global landing site access. Abort strategies were also considered from the lunar vicinity. “Anytime return” from the lunar surface is a desirable option that was analyzed along with options for orbital and surface loiter. -

Go-Around Decision-Making and Execution Project

Final Report to Flight Safety Foundation Go-Around Decision-Making and Execution Project Tzvetomir Blajev, Eurocontrol (Co-Chair and FSF European Advisory Committee Chair) Capt. William Curtis, The Presage Group (Co-Chair and FSF International Advisory Committee Chair) MARCH 2017 1 Acknowledgments We would like to acknowledge the following people and organizations without which this report would not have been possible: • Airbus • Johan Condette — Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses • Air Canada Pilots Association • Capt. Bertrand De Courville — Air France (retired) • Air Line Pilots Association, International • Capt. Dirk De Winter — EasyJet • Airlines for America • Capt. Stephen Eggenschwiler — Swiss • The Boeing Company • Capt. Alex Fisher — British Airways (retired) • Eurocontrol • Alvaro Gammicchia — European Cockpit Association • FSF European Advisory Committee • Harald Hendel — Airbus • FSF International Advisory Committee • Yasuo Ishihara — Honeywell Aerospace Advanced • Honeywell International Technology • International Air Transport Association • David Jamieson, Ph.D. — The Presage Group • International Federation of Air Line Pilots’ Associations • Christian Kern — Vienna Airport • The Presage Group • Capt. Pascal Kremer — FSF European Advisory Committee • Guillaume Adam — Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses • Richard Lawrence — Eurocontrol • John Barras – FSF European Advisory Committee • Capt. Harry Nelson — Airbus • Tzvetomir Blajev — Eurocontrol • Bruno Nero — The Presage Group • Karen Bolten — NATS • Zeljko Oreski — International -

FSF ALAR Briefing Note 7.1 -- Stabilized Approach

Flight Safety Foundation Approach-and-landing Accident Reduction Tool Kit FSF ALAR Briefing Note 7.1 — Stabilized Approach Unstabilized approaches are frequent factors in approach-and- causal factor in 45 percent of the 76 approach-and-landing landing accidents (ALAs), including those involving controlled accidents and serious incidents. flight into terrain (CFIT). The task force said that flight-handling difficulties occurred Unstabilized approaches are often the result of a flight crew who in situations that included rushing approaches, attempts to conducted the approach without sufficient time to: comply with demanding ATC clearances, adverse wind conditions and improper use of automation. • Plan; • Prepare; and, Definition • Conduct a stabilized approach. An approach is stabilized only if all the criteria in company standard operating procedures (SOPs) are met before or when Statistical Data reaching the applicable minimum stabilization height. The Flight Safety Foundation Approach-and-landing Accident Table 1 (page 134) shows stabilized approach criteria Reduction (ALAR) Task Force found that unstabilized recommended by the FSF ALAR Task Force. approaches (i.e., approaches conducted either low/slow or high/ fast) were a causal factor1 in 66 percent of 76 approach-and- Note: Flying a stabilized approach that meets the recommended landing accidents and serious incidents worldwide in 1984 criteria discussed below does not preclude flying a delayed- through 1997.2 flaps approach (also referred to as a decelerated approach) to comply with air traffic control (ATC) instructions. The task force said that although some low-energy approaches (i.e., low/slow) resulted in loss of aircraft control, most involved The following minimum stabilization heights are CFIT because of inadequate vertical-position awareness. -

The Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of Aerospace Engineering REAL-TIME PATH PLANNING AND AUTONOMOUS CONTROL FOR HELICOPTER AUTOROTATION A Dissertation in Aerospace Engineering by Thanan Yomchinda 2013 Thanan Yomchinda Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 The dissertation of Thanan Yomchinda was reviewed and approved* by the following: Joseph F. Horn Associate Professor of Aerospace Engineering Dissertation Co-Advisor Co-Chair of Committee Jacob W. Langelaan Associate Professor of Aerospace Engineering Dissertation Co-Advisor Co-Chair of Committee Edward C. Smith Professor of Aerospace Engineering Christopher D. Rahn Professor of Mechanical Engineering George A. Lesieutre Professor of Aerospace Engineering Head of the Department of Aerospace Engineering *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Autorotation is a descending maneuver that can be used to recover helicopters in the event of total loss of engine power; however it is an extremely difficult and complex maneuver. The objective of this work is to develop a real-time system which provides full autonomous control for autorotation landing of helicopters. The work includes the development of an autorotation path planning method and integration of the path planner with a primary flight control system. The trajectory is divided into three parts: entry, descent and flare. Three different optimization algorithms are used to generate trajectories for each of these segments. The primary flight control is designed using a linear dynamic inversion control scheme, and a path following control law is developed to track the autorotation trajectories. Details of the path planning algorithm, trajectory following control law, and autonomous autorotation system implementation are presented. -

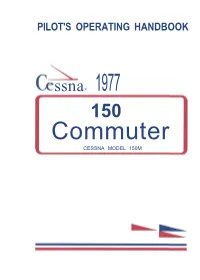

Cessna Model 150M Performance- Cessna Specifications Model 150M Performance - Specifications

PILOT'S OPERATING HANDBOOK ssna 1977 150 Commuter CESSNA MODEL 150M PERFORMANCE- CESSNA SPECIFICATIONS MODEL 150M PERFORMANCE - SPECIFICATIONS SPEED: Maximum at Sea Level 109 KNOTS Cruise, 75% Power at 7000 Ft 106 KNOTS CRUISE: Recommended Lean Mixture with fuel allowance for engine start, taxi, takeoff, climb and 45 minutes reserve at 45% power. 75% Power at 7000 Ft Range 340 NM 22.5 Gallons Usable Fuel Time 3.3 HRS 75% Power at 7000 Ft Range 580 NM 35 Gallons Usable Fuel Time 5. 5 HRS Maximum Range at 10,000 Ft Range 420 NM 22. 5 Gallons Usable Fuel Time 4.9 HRS Maximum Range at 10,000 Ft Range 735 NM 35 Gallons Usable Fuel Time 8. 5 HRS RATE OF CLIMB AT SEA LEVEL 670 FPM SERVICE CEILING 14, 000 FT TAKEOFF PERFORMANCE: Ground Roll 735 FT Total Distance Over 50-Ft Obstacle 1385 FT LANDING PERFORMANCE: Ground Roll 445 FT Total Distance Over 50-Ft Obstacle 107 5 FT STALL SPEED (CAS): Flaps Up, Power Off 48 KNOTS Flaps Down, Power Off 42 KNOTS MAXIMUM WEIGHT 1600 LBS STANDARD EMPTY WEIGHT: Commuter 1111 LBS Commuter II 1129 LBS MAXIMUM USEFUL LOAD: Commuter 489 LBS Commuter II 471 LBS BAGGAGE ALLOWANCE 120 LBS WING LOADING: Pounds/Sq Ft 10.0 POWER LOADING: Pounds/HP 16.0 FUEL CAPACITY: Total Standard Tanks 26 GAL. Long; Range Tanks 38 GAL. OIL CAPACITY 6 QTS ENGINE: Teledyne Continental O-200-A 100 BHP at 2750 RPM PROPELLER: Fixed Pitch, Diameter 69 IN. D1080-13-RPC-6,000-12/77 PILOT'S OPERATING HANDBOOK Cessna 150 COMMUTER 1977 MODEL 150M Serial No. -

(VL for Attrid

ECCAIRS Aviation 1.3.0.12 Data Definition Standard English Attribute Values ECCAIRS Aviation 1.3.0.12 VL for AttrID: 391 - Event Phases Powered Fixed-wing aircraft. (Powered Fixed-wing aircraft) 10000 This section covers flight phases specifically adopted for the operation of a powered fixed-wing aircraft. Standing. (Standing) 10100 The phase of flight prior to pushback or taxi, or after arrival, at the gate, ramp, or parking area, while the aircraft is stationary. Standing : Engine(s) Not Operating. (Standing : Engine(s) Not Operating) 10101 The phase of flight, while the aircraft is standing and during which no aircraft engine is running. Standing : Engine(s) Start-up. (Standing : Engine(s) Start-up) 10102 The phase of flight, while the aircraft is parked during which the first engine is started. Standing : Engine(s) Run-up. (Standing : Engine(s) Run-up) 990899 The phase of flight after start-up, during which power is applied to engines, for a pre-flight engine performance test. Standing : Engine(s) Operating. (Standing : Engine(s) Operating) 10103 The phase of flight following engine start-up, or after post-flight arrival at the destination. Standing : Engine(s) Shut Down. (Standing : Engine(s) Shut Down) 10104 Engine shutdown is from the start of the shutdown sequence until the engine(s) cease rotation. Standing : Other. (Standing : Other) 10198 An event involving any standing phase of flight other than one of the above. Taxi. (Taxi) 10200 The phase of flight in which movement of an aircraft on the surface of an aerodrome under its own power occurs, excluding take- off and landing. -

Airworthiness Requirements for the Type Certification of Airships in the Categories Normal and Commuter

Section 1 LFLS Airworthiness Requirements Lufttüchtigkeitsforderungen for the type certification of für die Prüfung und Zulassung von airships in the categories Luftschiffen der Kategorien Normal and Commuter Normal und Zubringer (LFLS) References: Referenzen: - Announcement: NfL II - 94/93 - Bekanntmachung: NfL II - 103/99 - Publication in Bundesanzeiger: - Veröffentlichung im Bundesanzeiger: BAnz. Volume 53, page 9286, Nr. 185 BAnz. Jahrgang 53, Seite 6813, Nr. 72 - Effective date: 13. April 2001 - inkraftgetreten: 13. April 2001 - Amendments: - Änderungen: NfL II - 25/01 (correction § 341) NfL II - 25/01 (Korrektur § 341) - This Implemenation Order has been notified under - Diese Durchführungsverordnung wurde unter der the No. 1996/420/D with the directives 83/189/EEC, Nr. 1996/420/D entsprechend den Richtlinien 88/182/EEC and 94/10/EC concerning an 83/189/EWG, 88/182/EWG und 94/10/EG betreffend information procedure in the field of standards and eines Informationsverfahrens auf dem Gebiet der technical negotiations Normen und technischen Vorschriften notifiziert. In Hinblick auf die zu erwartenden Zulassungen im Ausland erfolgte die Bekanntmachung der LFLS in englischer Sprache. Eine deutsche Übersetzung wird angefertigt, sobald hierfür ein Bedarf erkennbar wird. FOREWORD These Airworthiness Requirements for Airships have been based on the report "Airship Design Criteria" of the US Department of Transportation, Paper No. FAA P-8110-2, change 1, dated July 24, 1992. The purpose of the FAA report was to provide acceptable airworthiness requirements for the type certification of conventional, near- equilibrium, non-rigid airships. The report contained the design requirements necessary to provide an equivalent level of safety to that prescribed in 14 CFR 21.17(b) for special classes of aircraft. -

August 2020 Aviationweek.Com/BCA Case Study: Turkish Well, Maybe They Were

Safety The Human-Engine Interface Many problems, one easy solution BY JAMES ALBRIGHT [email protected] y first piece of aircraft auto- you to engage the autothrottles for autothrottles had a role to play leading SAICLE/GETTY IMAGES mation was a flight director in takeoff and then simply forget about up to the scene of the accident. Four fol- the Northrop T-38. It was pure them until after landing. And, I must low — each with an autothrottle prob- magic: Two mechanical needles admit, sometimes I forget about them. lem. Let’s see if we can come up with a Mcame into view, one for course and an- But these days, I mostly don’t trust solution. other for glidepath, and you simply flew them during the climb because with the airplane so as to center them. Over the wrong mode of the autopilot they Case Study: Gulfstream the next few years the crossbars turned can result in a stall. Oh yes, I don’t trust GIV, G-GMAC to vee bars, but there was nothing them en route because changing envi- earthshaking until one of my airplanes ronmental conditions can leave us short Problem: There has been a divergence of allowed us to couple those bars to the of thrust. And then there is the descent. opinion in the Gulfstream world on the autopilot. Now, that was neat. And don’t get me started about the ap- proper way to engage and disengage Then came an autothrottle system proach phase! OK, OK. I guess I just the autothrottles. There are two sets of that was good for an ILS approach and don’t trust them.