Structural Change in Demand for FAFH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monthly BL Report

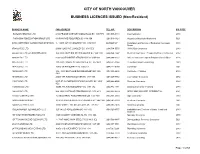

CITY OF NORTH VANCOUVER BUSINESS LICENCES ISSUED (Non-Resident) BUSINESS NAME CNV ADDRESS TEL. NO. DESCRIPTION IPS CODE EATON'S HEATING LTD 2466 FRISKIE AVEPORT COQUITLAM BC V3B 7P9 (604)535-8434 Gas Contractor 2383 PARAGON REMEDIATION GROUP LTD 8815 HARVIE RDSURREY BC V4N 4B9 (604)513-1324 Hazardous Materials Abatement 5621 (EASI) ENTRANCE AUTOMATION SYSTEMS 1 - 13015 84TH AVESURREY BC V3W 1B3 6045945127 Installation and Service of Pedestrian Automatic 2389 Doors 07048237 BC LTD 20363 62ND AVE LANGLEY BC V3A 5E6 (604)534-5555 HVAC/Gas Contractor 2383 0880441 BC LTD O/A EVENTPOWER 104-8838 HEATHER STVANCOUVER BC V6P 3S8 (604)524-1967 Electrical Contractor : Temporary Power for Events 2382 0986001 BC LTD 8563 GOVERNMENT STBURNABY BC V3N 4S9 (604)688-3157 Athletic Instructor - Sports Programs for Children 6116 0987762 BC LTD 338-3381 CAMBIE STVANCOUVER BC V5Z 4R3 (604)561-3366 Demolition & Excavating 2389 1024753 BC LTD 15075 59 AVESURREY BC V3S 3T2 (604)771-9703 Contractor 2361 1025689 BC LTD 108 - 8331 EASTLAKE DRIVEBURNABY BC V5A (604)444-2242 Contractor - Painting 2389 4W2 1049936 BC LTD 260 E 4TH AVEVANCOUVER BC V5T 1G5 (604)628-8752 Low Voltage Contractor 2382 1103735 BC LTD 5337 ST CATHERINES STVANCOUVER, BC V5W (250)886-6002 Electrical Contractor 2382 3G2 11466884 BC LTD 14485 88A AVENUESURREY BC V3R 1A2 (604)782-1971 Building Contractor- Framing 2389 1243035 BC LTD 208-3900 HASTINGS STBURNABY BC V5C 6C1 (403)880-9939 NEW HOME BUILDER- RESIDENTIAL 2361 1339022 ONTARIO LTD 75 INDUSTRIAL RDTOTTENHAM ON L0G 1W0 (905)936-5888 Sign -

Lethbridgecovidsupportsapril6.Pdf

helpseeker.org SOCIAL AND HEALTH EMERGENCY RESPONSE SERVICES FOR COVID-19/CORONAVIRUS LETHBRIDGE This list was pulled April 6th, 2020 at 9 am MST and will be updated every 24hrs Page 1 LOCATIONS 244 A&W LETHBRIDGE LOCATIONS 150 3 Ave S, Lethbridge, AB T1J 4L2, Canada Location COVID19 Update: Mobile ordering & drive-thru available. Given the ever-changing situation with COVID-19, the information here may not be up to date. Please call ahead to verify opening hours at your local restaurant. While all A&W dining rooms are now closed, drive-thrus are still open and many restaurants offer delivery via one of our delivery partners. ABILITY RESOURCE CENTRE Monday – Friday: 8:00 am – 4:30 pm 14033293911 [email protected] Location http://www.abilityresource.ca 1610 29 St N, Lethbridge, AB T1H 5L3, Canada COVID19 Update: We are CLOSED due to COVID-19 until further notice. Ability Resource Centre is a place for individuals to build friendships, learn, be productive, explore interests and talents, develop skills and gain confidence. Individuals are supported to be involved in general community social, recreational, educational, arts and culture activities. Community Access Services supports working-aged youth and adults with disabilities to achieve their goals in the life areas of: Independence, Well-Being and Community Connections. This service typically appeals to people who do not have employment as a short term goal, but who desire: increased community involvement, interpersonal relationship building, development of skills related to their needs, interests and talents, pre-employment skill development, and support for their health and well-being goals. -

2019 Annual Report Our Conservation Supporters

2019 ANNUAL REPORT TO THE OUR CONSERVATION SUPPORTERS Partnerships with a Purpose Every piece of wetland or associated upland habitat A special thanks to our conserved by Ducks Unlimited Canada (DUC) is the result of partnerships. These partnerships are the government partners: foundation of DUC’s conservation leadership and the The governments listed below The State of Idaho reason why we so clearly envision a future for wetland have provided instrumental The State of Indiana conservation in North America. support in Canada over the The State of Kansas Today, this continent-wide network of conservation past year. staff, volunteers and supporters ensures that Ducks The Government of Canada The State of Kentucky Unlimited Canada, Ducks Unlimited, Inc., and The Government of Alberta The State of Louisiana Ducks Unlimited Mexico play leadership roles in The State of Maine international programs like the North American The Government of British Waterfowl Management Plan (NAWMP). Established Columbia The State of Maryland in 1986, NAWMP is a partnership of federal, provincial, The Government of Manitoba The State of Massachusetts state and municipal governments, nongovernmental The Government of The State of Michigan organizations, private companies and many individuals, New Brunswick all working towards achieving better wetland habitat The State of Minnesota for the benefit of waterfowl, other wetland associated The Government of The State of Mississippi wildlife and people. DUC is proud to be closely Newfoundland and Labrador The State of Missouri associated with NAWMP, one of the most successful The Government of the conservation initiatives in the world. Northwest Territories The State of Nebraska The State of Nevada The North American Wetlands Conservation Act The Government of (NAWCA), enacted by the U.S. -

Give Kids a Chance to Dream

SOSCONNECTION2009 Issue #1 SOS Children’s Village British Columbia KIDS AT SOS BC Fly to the North Pole to Find Santa Give Kids a Chance to Dream dorable eyes wide open, a n August 28, 1963 an amazing speech known as “I have a Dream”, tiny giggle and then a hushed, was spoken with grace and power by Martin Luther King, in the “Santa” . the joy and wonder of the youngest participant on midst of a time of tremendous and dangerous turbulence. As we Athe “Flight in Search of Santa” was all know, the speech has become one of the most well known and plain to see. Made possible by Air loved in our time. Its effects are lasting because it provides the assurance that O Transat and an invitation from Variety there is always hope, always the possibility of a just future, and, that indeed, Club, seven awe-struck kids from SOS a dream can come true. Children’s Village, the Director of the The legacy for children in foster care is reflected in statistics that have Village Corina Carroll, Philanthropist highlighted the fact that all too many of these children have lost too much Joanne Griffiths, and a social worker and gained too little. In the middle of their turbulence they are looking for from VACFSS, flew high with anticipation adults who they can trust with their dreams. in search of Santa. Children living in foster care, by definition, undergo life-shattering In the midst of a winter storm we upheaval. Amongst foster children and youth there are higher rates of ventured to the airport safe and sound in physical health problems, depression, suicide, mental health issues and our limo van. -

Corporate Registry Registrar's Periodical Template

Service Alberta ____________________ Corporate Registry ____________________ Registrar’s Periodical REGISTRAR’S PERIODICAL, FEBRUARY 15, 2013 SERVICE ALBERTA Corporate Registrations, Incorporations, and Continuations (Business Corporations Act, Cemetery Companies Act, Companies Act, Cooperatives Act, Credit Union Act, Loan and Trust Corporations Act, Religious Societies’ Land Act, Rural Utilities Act, Societies Act, Partnership Act) 0941168 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1718482 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Registered 2013 JAN 10 Registered Address: 223084 Corporation Incorporated 2013 JAN 15 Registered HWY 56/BOX 275, HUSSAR ALBERTA, T0J1S0. No: Address: 165 WENTWORTH PLACE S.W., 2117227278. CALGARY ALBERTA, T3H 4L5. No: 2017184827. 0958227 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1719284 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Registered 2013 JAN 09 Registered Address: 3RD Corporation Incorporated 2013 JAN 04 Registered FLOOR, 4943 - 50TH STREET, RED DEER Address: STE. 11, 1915-32ND AVENUE N.E., ALBERTA, T4N1Y1. No: 2117227161. CALGARY ALBERTA, T2E 7C8. No: 2017192846. 0959184 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1719286 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Registered 2013 JAN 03 Registered Address: 456 Corporation Incorporated 2013 JAN 08 Registered MCKENZIE LAKE BAY SE, CALGARY ALBERTA, Address: 182 TUSCANY VISTA ROAD NW, T2Z2H4. No: 2117215737. CALGARY ALBERTA, T3L 3B5. No: 2017192861. 0959539 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 1719288 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Registered 2013 JAN 09 Registered Address: SUITE Corporation Incorporated 2013 JAN 09 Registered 1400 - 10303 JASPER AVENUE, EDMONTON Address: 143 WOODBEND WAY, OKOTOKS ALBERTA, T5J3N6. No: 2117225231. ALBERTA, T1S 1L7. No: 2017192887. 101188413 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. Other 1719291 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2013 JAN 14 Corporation Incorporated 2013 JAN 09 Registered Registered Address: 13539 83RD ST, EDMONTON Address: 145 COUGARTOWN CIRCLE S.W., ALBERTA, T5E2X4. -

Schoolbucks Order Deadline: Thursday, Feb

Order deadline: Thursday, Jan. 21 → Pick-up date: Thursday, Jan.28 SchoolBucks Order deadline: Thursday, Feb. 4 → Pick-up date: Thursday, Feb. 10 Order deadline: Thursday, Feb. 18 → Pick-up date: Thursday, Feb. 25 S T . T H O M A S A Q U I N A S Order deadline: Thursday, Mar. 4 → Pick-up date: Thursday, Mar. 11 Order deadline: Thursday, Apr. 8 → Pick-up date: Thursday, Apr. 15 Order deadline: Thursday, Apr. 22 → Pick-up date: Thursday, Apr.29 Order deadline: Thursday, May 6 → Pick-up date: Thursday, May 13 Order deadline: Thursday, May 20 → Pick-up date: Thursday, May27 Order deadline: Thursday, June 3 → Pick-up date: Thursday, June 10 Name (please print): Name of student(s): Grade(s): Email Address: Cell Number: I authorize the student(s) listed above to pick-up my SchoolBucks order: Parent’s signature: Date: To complete this form: 1. On the reverse side, choose the retailers and write the number of certificates/gift cards you wish to purchase. 2. Total the amounts. 3. Fill in Method of Payment and Total Payment below. 4. Submit your order and payment to the school office by the ORDER Deadline date (above) by 3:30pm. 5. Please make cheques payable to STA. METHOD OF PAYMENT: Cheque Amount $ Cash Amount $ Cheque Number TOTAL ORDER $ SCHOOLBUCKS PICK-UP: • Please pick-up your SchoolBucks at the school on the specified Pick-Up Date (above) after 3:00 pm. • If you are unable to pick-up at that time, you may pick- up your order at the school office anytime during school office hours (8:00 am - 4:00 pm). -

BUSINESS LICENCES ISSUED (Resident)

CITY OF NORTH VANCOUVER BUSINESS LICENCES ISSUED (Resident) BUSINESS NAME CNV ADDRESS TEL. NO. DESCRIPTION IPS CODE 464133 BC LTD RIDGEWAY AVE V7L 3P9 (604)984-8973 Home Office Use - Landscaping Contractor 2389 0735531 BC LTD CARRIE CATES CRT V7M 3K7 (604)987-1200 Retail Coffee Merchant 4452 0752595 BC LTD LONSDALE AVE V7M 2K3 (604)924-9310 Tanning Studio/Lash Extension Services 8121 0768206 BC LTD MARINE DR V7P 1S3 604-904-9700 General Insurance Agency 5242 0779285 BC LTD W 3RD ST V7M 1G3 (604)987-3030 Gas Station with Convenience Store 4471 0821537 BC LTD E 3RD ST V7L 1E5 (604)985-5477 Restaurant 7226 0825061 BC LTD LONSDALE AVE V7M 2K4 (604)984-9977 Restaurant 7226 0852207 BC LTD W 1ST ST V7M 1B3 604-980-5973 Real Estate Property Managers 5312 0855093 BC LTD LONSDALE AVE V7M 2E5 (778)340-3449 Restaurant & Lounge 7226 0863373 BC LTD CARRIE CATES CRT V7M 3K7 Take Out Service - Salad Garden 7229 0863931 BC LTD LONSDALE AVE V7M 2G1 (604)971-2153 Cafe-Licenced 7226 0875953 BC LTD E 1ST ST V7L 1B4 (604)760-3337 Clothing Warehouse 4931 0931284 BC LTD E 8TH ST V7L 1Z8 (604)401-5286 Acupuncture Therapy-at home and at client's homes 6213 0933541 BC LTD WALLACE MEWS V7L 0B9 (604)929-7437 Full Service Seafood Restaurant 7227 0935877 BC LTD LONSDALE AVE V7M 2H5 (604)971-4377 Full Service Restaurant 7226 0939333 BC LTD E 9TH ST V7L 2B7 (778)858-8830 Home Occupation Use - General Contractor 2361 0952768 BC LTD E 14TH ST V7L 2N3 604 987-5881 Retail Bakery 4452 0972998 BC LTD LONSDALE AVE V7M 2J3 (604)315-0374 Yoga Studio 6116 0977499 BC LTD W ESPLANADE V7M 3J3 (604)807-7029 Pharmacy 4462 0981760 B.C. -

21 Annual Awards of Excellence Edition

Cover Photo: Photo: Cover | Sechelt Residence BC Private Seagull Enterprises BRITISH COLUMBIA CHAPTER Honouring the finest in quality and service in the architectural woodwork industry BENCHMARKTHE 21ST ANNUAL AWARDS OF EXCELLENCE EDITION FALL 2011 1 AWMAC is committed to the architectural wood- work industry through Introducing the winners....... our role as a facilitator of outstanding quality and exceptional service and as a conduit for knowledge to Above and Beyond Award everyone engaged in the construction industry. In 2008, Steve Glegg of Stirling Woodworks envisioned a Each of the 45 projects showcased green initiative in the architectural woodwork industry. in this edition of The Benchmark Steve piloted the Sustainable Architectural Woodwork From the Executive Director the Executive From confirms that BC Chapter members (SAW) certification program from conception to its produce outstanding architectural successful launch in 2011! woodwork. We have booked the 2012 Awards for Past President Frank Beck presents the Above and Beyond Award September 20th at the Vancouver to Steve Glegg. Convention Centre West. Don’t miss it! Sales Representative of the Year Award Moira Rowan Awarded to Steve Mahovlic of Hardwoods Specialty Products. Steve provided the best, most prompt and professional service to manufacturer members during Congratulations to all the year 2010. the winners of the 2011 AWMAC BC Awards of Steve Mahovlic receives the Sales Rep of the Year Award from Excellence. This event is Tony Lucas, last year’s recipient. the largest of its kind and is growing by the year. We encourage you to start thinking about which projects to submit for Supplier of the Year Award From the President From next year as it provides a fantastic Presented to Hardwoods Specialty Products. -

Stars of Vancouver 2015 Revealed

Stars of Vancouver 2015 Revealed Vancouver Courier February 26, 2015 03:50 PM The City of Vancouver has been named everything from Best Destination in Canada (Travel Weekly) to second best city in the world (Telegraph Travel Awards) to World’s Healthiest Place to Live (Time Magazine) and a lot of that has to do with its residents, businesses, restaurants, services and attractions. And while international accolades are certainly noteworthy and appreciated, it’s the insiders, such as Vancouver Courier readers, who can truly offer great advice on the best of the best this city has to offer. That’s just one of the reasons the Courier’s Stars of Vancouver Readers’ Choice Awards continue to be so anticipated year after year. This annual best-of compilation highlights not only long-established businesses, attractions and services, but also recognizes the new kids on the block, including the hottest new restaurants and food trucks, festivals, art galleries, décor shops dedicated to style and design, and clothing and accessory stores offering the latest fashion trends. So whether you’re a long-time resident or new arrival, let Stars of Vancouver 2015 act as your guide to some of this city’s deep-rooted favourites, best-kept secrets and hidden gems. Powered by Publish for Free (https://issuu.com/publishers?entryPoint=embed) (https://issuu.com/explore) ARTS + CULTURE Art Gallery/Studio 1. Vancouver Art Gallery 2. Ayden Gallery 3. Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery Classical Music Ensemble 1. Vancouver Symphony Orchestra 2. Musica Intima 3. UBC Symphony Orchestra Dance Company 1. Arts Umbrella 2. -

FOR SALE 2.89 Acre Development Site

FOR SALE 2.89 Acre Development Site 1912 Columbia Avenue Castlegar, BC Property Summary The 2.89 acre (125,888 SF) property is one legal parcel located at 1912 Columbia Avenue, Castlegar BC. Situated along Columbia Avenue leading to Trail, BC in the south and right at the turn off point for Highway 3 connecting the west coast to Alberta. The property offers excellent highway visibility for any motorists driving by Castlegar. The property is currently vacant land and is zoned C-1: Regional commercial Zone which would be perfect for any hotels/motels or quick service restaurants. Danny Su NAI Commercial Associate 1075 W Georgia St, Suite 1300 Retail Investment Sales Vancouver, BC V6E 3C9 604 691 6678 +1 604 683 7535 [email protected] naicommercial.ca 1 2 3 4 5 6 25 26 8 AVE 8 27 AVE 8 7 10 8 9 CROWSN ES 97 T H West Kootenay 11 W Regional Airport Y 12 COLUMBIA AVE 3 22 24 13 SUBJECT PROPERTY 14 3 23 20 16 15 17 21 18 19 ALONG COLUMBIA AVE 1. Glacier Honda 10. Castleaird Plaza 19. Canadian Tire 2. Castlegar Kia 11. City Furniture & Appliances 20. Boston Pizza 3. Castlegar Hyundai 12. Kootenay Centre Cinemas 21. Petro Canada 4. Kalawsky Chevrolet Buick GMC 13. Shoppers Drug Mart 22. Chevron 5. Safeway Castlegar 14. Uptown Centre 23. Sandman Hotel Castlegar 6. Heritage Credit Union 15. McDonald’s 24. Quality Inn 7. CIBC Bank 16. A&W Canada 25. Shell 8. Dairy Queen Grill & Chill 17. Panago Pizza 26. Super 8 9. -

Evan Bird + Paul Farrant

SPRING / SUMMER 2017 PEACE ARCH HOSPITAL FOUNDATION PEACE ARCH HOSPITAL IS BREATHING EASIER THANKS TO TB VETS LE CIRQUE DU SOIRÉE BRINGS A SPECTACULAR NIGHT CIRCUS TO WHITE ROCK HOMELIFE BENCHMARK REALTY GIVES BACK IN A BIG WAY THE 2016/2017 DONOR LIST EVAN BIRD + PAUL FARRANT MEET Two White Rock firefighters fueling a dream for a community playground LEADING THE WAY WELCOME TO OUR NEWEST EDITION OF thrive! Welcome to summer! After a wet and chilly spring, Mother Nature has finally smiled down upon the Peninsula. With all of this great weather, there is no better time to get outside and enjoy some fun activity. With this in mind, we are thrilled to tell you about a brand new all-abilities and all-ages playground currently in development for Centennial Park. This is being built in collaboration with the City of White Rock and White Rock Firefighters, who have been championing an all-abilities park on East Beach since 2009. This project is the first for our Healthy Community initiative and is in keeping with the Foundation’s strategic goal to support projects and programs that effect change in health and wellness upstream. As the first phase of a three-phase plan that also includes a trail down to the waterfront that will eventually link to the proposed park on East Beach, we couldn’t be more excited for these innovative new ways for the whole family to be active in our community. Learn more about the new playground and how White Rock firefighter Evan Bird’s original vision inspired us to take action on page 6. -

Exhibitor List

EXHIBITOR LIST 1-9 BizComm Inc., Brokerage Copper Branch F www.bizcomm.ca www.copperbranch.ca 180 Smoke Vape Store .................................................... 508 .................................................... 432 Federal Wireless www.180smoke.ca Communications Inc .................................................... 202 Bodhi Bar - Organic Juice and Crackboom www.federalwc.com Smoothie Bar www.crackboom.ca .................................................... 150 241 Pizza www.bodhibar.ca ............................................ 436, 438 www.241pizza.com .................................................... 133 FlagFranchise .....................................523, 525, 527 Cultures www.flagfranchise.com A Boustan www.cultures-restaurants.com ............................................ 441, 443 www.boustan.ca ...................101,103,105,107,109,111 AGTA Home Health Care ............................................. 402,404 Foodtastic Curb-Ease www.foodtastic.ca www.agtafranchises.com www.curb-easefranchise.com ............................................ 126, 128 B-Protek ............................................. 305,307 www.bprotek.com .................................................... 701 Franchise Marketing Aisle 24 .................................................... 236 Custodia Senior Support www.aisle24.ca Systems BrandLoyal www.custodia.com .................................................... 428 ............................................ 820, 822 www.fmsfranchise.com www.brandloyal.io ...................................................