Journal Pre-Proof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chemicals in the Fourth Report and Updated Tables Pdf Icon[PDF

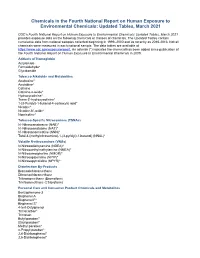

Chemicals in the Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals: Updated Tables, March 2021 CDC’s Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals: Updated Tables, March 2021 provides exposure data on the following chemicals or classes of chemicals. The Updated Tables contain cumulative data from national samples collected beginning in 1999–2000 and as recently as 2015-2016. Not all chemicals were measured in each national sample. The data tables are available at https://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport. An asterisk (*) indicates the chemical has been added since publication of the Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals in 2009. Adducts of Hemoglobin Acrylamide Formaldehyde* Glycidamide Tobacco Alkaloids and Metabolites Anabasine* Anatabine* Cotinine Cotinine-n-oxide* Hydroxycotinine* Trans-3’-hydroxycotinine* 1-(3-Pyridyl)-1-butanol-4-carboxylic acid* Nicotine* Nicotine-N’-oxide* Nornicotine* Tobacco-Specific Nitrosamines (TSNAs) N’-Nitrosoanabasine (NAB)* N’-Nitrosoanatabine (NAT)* N’-Nitrosonornicotine (NNN)* Total 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol) (NNAL)* Volatile N-nitrosamines (VNAs) N-Nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA)* N-Nitrosoethylmethylamine (NMEA)* N-Nitrosomorpholine (NMOR)* N-Nitrosopiperidine (NPIP)* N-Nitrosopyrrolidine (NPYR)* Disinfection By-Products Bromodichloromethane Dibromochloromethane Tribromomethane (Bromoform) Trichloromethane (Chloroform) Personal Care and Consumer Product Chemicals and Metabolites Benzophenone-3 Bisphenol A Bisphenol F* Bisphenol -

Pfoa) Or Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (Pfos

National Toxicology Program NTP U.S. Department of Health and Human Services NTP Monograph Immunotoxicity Associated with Exposure to Perfluorooctanoic Acid or Perfluorooctane Sulfonate September 2016 NTP MONOGRAPH ON IMMUNOTOXICITY ASSOCIATED WITH EXPOSURE TO PERFLUOROOCTANOIC ACID (PFOA) OR PERFLUOROOCTANE SULFONATE (PFOS) September, 2016 Office of Health Assessment and Translation Division of the National Toxicology Program National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences National Institutes of Health U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Systematic Review of Immunotoxicity Associated with Exposure to PFOA or PFOS TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ...............................................................................................................................II List of Table and Figures ................................................................................................................... IV Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Peer Review Of The Draft NTP Monograph ......................................................................................... 2 Peer-Review Panel .............................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Objective and Specific Aims ............................................................................................................... -

PFAS MCL Technical Support Document

ATTACHMENT 1 New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Technical Background Report for the June 2019 Proposed Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) and Ambient Groundwater Quality Standards (AGQSs) for Perfluorooctane sulfonic Acid (PFOS), Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), Perfluorononanoic Acid (PFNA), and Perfluorohexane sulfonic Acid (PFHxS) And Letter from Dr. Stephen M. Roberts, Ph.D. dated 6/25/2019 – Findings of Peer Review Conducted on Technical Background Report June 28, 2019 New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Technical Background Report for the June 2019 Proposed Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) and Ambient Groundwater Quality Standards (AGQSs) for Perfluorooctane sulfonic Acid (PFOS), Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), Perfluorononanoic Acid (PFNA), and Perfluorohexane sulfonic Acid (PFHxS) June 28, 2019 Table of Contents Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... iii Section I. Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... 1 Section II. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 2 Section III. Reference Dose Derivation ........................................................................................................ -

Health Effects Support Document for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA)

United States Office of Water EPA 822-R-16-003 Environmental Protection Mail Code 4304T May 2016 Agency Health Effects Support Document for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) Perfluorooctanoic Acid – May 2016 i Health Effects Support Document for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water (4304T) Health and Ecological Criteria Division Washington, DC 20460 EPA Document Number: 822-R-16-003 May 2016 Perfluorooctanoic Acid – May 2016 ii BACKGROUND The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), as amended in 1996, requires the Administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to periodically publish a list of unregulated chemical contaminants known or anticipated to occur in public water systems and that may require regulation under SDWA. The SDWA also requires the Agency to make regulatory determinations on at least five contaminants on the Contaminant Candidate List (CCL) every 5 years. For each contaminant on the CCL, before EPA makes a regulatory determination, the Agency needs to obtain sufficient data to conduct analyses on the extent to which the contaminant occurs and the risk it poses to populations via drinking water. Ultimately, this information will assist the Agency in determining the most appropriate course of action in relation to the contaminant (e.g., developing a regulation to control it in drinking water, developing guidance, or deciding not to regulate it). The PFOA health assessment was initiated by the Office of Water, Office of Science and Technology in 2009. The draft Health Effects Support Document for Perfluoroctanoic Acid (PFOA) was completed in 2013 and released for public comment in February 2014. -

Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) November 2017 TECHNICAL FACT SHEET – PFOS and PFOA

Technical Fact Sheet – Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) November 2017 TECHNICAL FACT SHEET – PFOS and PFOA Introduction At a Glance This fact sheet, developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Manmade chemicals not (EPA) Federal Facilities Restoration and Reuse Office (FFRRO), provides a naturally found in the summary of two contaminants of emerging concern, perfluorooctane environment. sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), including physical and Fluorinated compounds that chemical properties; environmental and health impacts; existing federal and repel oil and water. state guidelines; detection and treatment methods; and additional sources of information. This fact sheet is intended for use by site managers who may Used in a variety of industrial address these chemicals at cleanup sites or in drinking water supplies and and consumer products, such for those in a position to consider whether these chemicals should be added as carpet and clothing to the analytical suite for site investigations. treatments and firefighting foams. PFOS and PFOA are part of a larger group of chemicals called per- and Extremely persistent in the polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs). PFASs, which are highly fluorinated environment. aliphatic molecules, have been released to the environment through Known to bioaccumulate in industrial manufacturing and through use and disposal of PFAS-containing humans and wildlife. products (Liu and Mejia Avendano 2013). PFOS and PFOA are the most Readily absorbed after oral widely studied of the PFAS chemicals. PFOS and PFOA are persistent in the exposure. Accumulate environment and resistant to typical environmental degradation processes. primarily in the blood serum, As a result, they are widely distributed across all trophic levels and are found kidney and liver. -

Microbiota and Obesogens: Environmental Regulators of Fat Storage

Microbiota and obesogens: environmental regulators of fat storage John F. Rawls, Ph.D. Department of Molecular Genetics & Microbiology Center for Genomics of Microbial Systems Duke University School of Medicine Seminar outline 1. Introduction to the microbiota 2. Microbiota as environmental factors in obesity 3. Obesogens as environmental factors in obesity Seeing and understanding the unseen Antonie van Leewenhoek 1620’s: Described differences between microbes associated with teeth & feces during health & disease. Louis Pasteur 1850’s: Helps establish the “germ theory” of disease. 1885: Predicts that germ-free animals can not survive without “common microorganisms”. Culture-independent analysis of bacterial communities using 16S rRNA gene sequencing 16S rRNA 16S SSU rRNA 16S rRNA gene V1 V2 V3 V4 V5 V6 V7 V8 V9 Culture-independent analysis of bacterial communities using 16S rRNA gene sequencing plantbiology.siu.edu Phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA genes revealed 3 domains and a vast unappreciated diversity of microbial life You are here Carl Woese Glossary • Microbiota / microflora: the microorganisms of a particular site, habitat, or period of time. • Microbiome: the collective genomes of the microorganisms within a microbiota. • Germ-free / axenic: of a culture that is free from living organisms other than the host species. • Gnotobiotic: of an environment for rearing organisms in which all the microorganisms are either excluded or known. Current techniques for microbiome profiling Microbial community Morgan et al. (2012) Trends in -

Regulation of Immune Cells by Eicosanoid Receptors

Regulation of Immune Cells by Eicosanoid Receptors The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Kim, Nancy D., and Andrew D. Luster. 2007. “Regulation of Immune Cells by Eicosanoid Receptors.” The Scientific World Journal 7 (1): 1307-1328. doi:10.1100/tsw.2007.181. http://dx.doi.org/10.1100/ tsw.2007.181. Published Version doi:10.1100/tsw.2007.181 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:37298366 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Review Article Special Issue: Eicosanoid Receptors and Inflammation TheScientificWorldJOURNAL (2007) 7, 1307–1328 ISSN 1537-744X; DOI 10.1100/tsw.2007.181 Regulation of Immune Cells by Eicosanoid Receptors Nancy D. Kim and Andrew D. Luster* Center for Immunology and Inflammatory Diseases, Division of Rheumatology, Allergy, and Immunology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston E-mail: [email protected] Received March 13, 2007; Revised June 14, 2007; Accepted July 2, 2007; Published September 1, 2007 Eicosanoids are potent, bioactive, lipid mediators that regulate important components of the immune response, including defense against infection, ischemia, and injury, as well as instigating and perpetuating autoimmune and inflammatory conditions. Although these lipids have numerous effects on diverse cell types and organs, a greater understanding of their specific effects on key players of the immune system has been gained in recent years through the characterization of individual eicosanoid receptors, the identification and development of specific receptor agonists and inhibitors, and the generation of mice genetically deficient in various eicosanoid receptors. -

Perfluorooctanoic Acid (Pfoa) and Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid (Pfos)

WATER QUALITY FACT SHEET: PERFLUOROOCTANOIC ACID (PFOA) AND PERFLUOROOCTANESULFONIC ACID (PFOS) Chemical Properties: • PFOA and PFOS are fluorinated organic chemicals that are part of a larger man-made chemical group referred to as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), which are resistant to heat, water, and oil. • The chemicals have been used in consumer products such as carpets, clothing, fabrics for furniture, paper packaging for food, and other materials (e.g., cookware) designed to be waterproof, stain- resistant or non-stick. • They also have been used in fire-retarding foam at airfields, military bases, and various industrial processes. • PFOA and PFOS have been the most extensively produced and studied PFAS. PFAS also includes GenX chemicals and perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS) which require further study. • PFAS tends to accumulate in groundwater with contamination typically localized and associated with facilities where the chemicals were produced or used to manufacture other products. Health Concerns: • In 2016, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) issued a lifetime health advisory for PFOA and PFOS for drinking water. Municipalities were advised that they should notify their customers of the presence of levels over 70 ppt (0.07 µg/L) in community water supplies. • Studies indicate that PFOA and PFOS may result in adverse health effects including developmental effects to fetuses during pregnancy or breastfed infants, cancer, liver effects, immune effects, thyroid effects, and cholesterol changes. Regulatory Considerations: • The USEPA has not regulated PFOA and PFOS. There is no Federal MCL or MCLG. • In August 2019, the California State Water Resources Control Board Division of Drinking Water (DDW) updated notification levels for PFOA and PFOS from 14 ppt to 5.1 ppt for PFOA and from 13 ppt to 6.5 ppt for PFOS. -

Perfluorooctanoic Acid Levels, Nuclear Receptor Gene Polymorphisms, And

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Associations among perfuorooctanesulfonic/ perfuorooctanoic acid levels, nuclear receptor gene polymorphisms, and lipid levels in pregnant women in the Hokkaido study Sumitaka Kobayashi1, Fumihiro Sata1,2, Houman Goudarzi1,3, Atsuko Araki1, Chihiro Miyashita1, Seiko Sasaki4, Emiko Okada5, Yusuke Iwasaki6, Tamie Nakajima7 & Reiko Kishi1* The efect of interactions between perfuorooctanesulfonic (PFOS)/perfuorooctanoic acid (PFOA) levels and nuclear receptor genotypes on fatty acid (FA) levels, including those of triglycerides, is not clear understood. Therefore, in the present study, we aimed to analyse the association of PFOS/PFOA levels and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in nuclear receptors with FA levels in pregnant women. We analysed 504 mothers in a birth cohort between 2002 and 2005 in Japan. Serum PFOS/ PFOA and FA levels were measured using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Maternal genotypes in PPARA (rs1800234; rs135561), PPARG (rs3856806), PPARGC1A (rs2970847; rs8192678), PPARD (rs1053049; rs2267668), CAR (rs2307424; rs2501873), LXRA (rs2279238) and LXRB (rs1405655; rs2303044; rs4802703) were analysed. When gene-environment interaction was considered, PFOS exposure (log10 scale) decreased palmitic, palmitoleic, and oleic acid levels (log10 scale), with the observed β in the range of − 0.452 to − 0.244; PPARGC1A (rs8192678) and PPARD (rs1053049; rs2267668) genotypes decreased triglyceride, palmitic, palmitoleic, and oleic acid levels, with the observed β in the range of − 0.266 to − 0.176. Interactions between PFOS exposure and SNPs were signifcant for palmitic acid (Pint = 0.004 to 0.017). In conclusion, the interactions between maternal PFOS levels and PPARGC1A or PPARD may modify maternal FA levels. Te genetic makeup of a person and the environmental factors might be responsible for regulating the levels of serum lipids, such as fatty acids (FA) and triglycerides (TG)1. -

Environmental Factors, Epigenetics, and Developmental Origin of Reproductive Disorders

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Reprod Manuscript Author Toxicol. Author Manuscript Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 March 01. Published in final edited form as: Reprod Toxicol. 2017 March ; 68: 85–104. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2016.07.011. Environmental Factors, Epigenetics, and Developmental Origin of Reproductive Disorders Shuk-Mei Hoa,b,c,d,*, Ana Cheonga,b, Margaret A. Adgente, Jennifer Veeversa,c, Alisa A. Suenf,g, Neville N.C. Tama,b,c, Yuet-Kin Leunga,b,c, Wendy N. Jeffersonf, and Carmen J. Williamsf,* aDepartment of Environmental Health, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio, United States of America bCenter for Environmental Genetics, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio, United States of America cCincinnati Cancer Center, Cincinnati, Ohio, United States of America dCincinnati Veteran Affairs Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio, United States of America eDepartment of Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, United States of America fReproductive Medicine Group, Reproductive & Developmental Biology Laboratory, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, United States of America gCurriculum in Toxicology, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States of America Abstract Sex-specific differentiation, development, and function of the reproductive system are largely dependent on steroid hormones. For this reason, developmental exposure -

Involvement of Microsomal Prostaglandin E Synthase-1-Derived Prostaglandin E2 in Chemical-Induced Carcinogenesis Shuntaro Hara (Showa University, Tokyo, Japan)

Book of Abstracts Thursday, October 23th SESSION 1: PGE2 in PATHOPHYSIOLOGY SESSION 2: PROSTAGLANDINS and CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM SESSION 3: NOVEL LIPID MEDIATORS and ADVANCES in LIPID MEDIATOR ANALYTICS Friday, October 24th YOUNG INVESTIGATOR SESSION SESSION 4: LIPOXYGENASES SESSION 5: ADIPOSE TISSUE and BIOACTIVE LIPIDS GOLD SPONSORS http://workshop-lipid.eu MAJOR SPONSORS 1 SPONSORS 2 SCIENTIFIC AND EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Gerard BANNENBERG Global Organization for EPA and DHA (GOED), Madrid, Spain E-mail: [email protected] Joan CLÀRIA Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics Hospital Clínic/IDIBAPS Villarroel 170 08036 Barcelona, Spain E-mail: [email protected] Per-Johan JAKOBSSON Karolinska Institutet Dept of Medicine 171 76 Stockholm, Sweden E-mail: [email protected] Jane A. MITCHELL NHLI, Imperial College, London SW3 6LY, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] Xavier NOREL INSERM U1148, Bichat Hospital 46, rue Henri Huchard 75018 Paris, France E-mail: [email protected] Dieter STEINHILBER Institut fuer Pharmazeutische Chemie Universitaet Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany E-mail: [email protected] Gökçe TOPAL Istanbul University Faculty of Pharmacy Department of Pharmacology Beyazit, 34116, Istanbul, Turkey E-mail: [email protected] Sönmez UYDEŞ DOGAN Istanbul University, Faculty of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmacology Beyazit, 34116, Istanbul, Turkey E-mail: [email protected] Tim WARNER The William Harvey Research Institute Barts& the London School of Medicine & Dentistry, United -

Hematopoietic Prostaglandin D2 Synthase Controls the Onset And

Hematopoietic prostaglandin D2 synthase controls SEE COMMENTARY the onset and resolution of acute inflammation 12–14 through PGD2 and 15-deoxy⌬ PGJ2 Ravindra Rajakariar*, Mark Hilliard†, Toby Lawrence‡, Seema Trivedi§, Paul Colville-Nash¶, Geoff Bellinganʈ, Desmond Fitzgerald†, Muhammad M. Yaqoob*, and Derek W. Gilroy**†† *Department of Experimental Medicine, Nephrology, and Critical Care, William Harvey Research Institute, Charterhouse Square, London EC1M 6BQ, United Kingdom; †Conway Institute, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland; ‡Institute of Cancer, Centre for Translational Oncology, Charterhouse Square, London EC1M 6BQ, United Kingdom; §Leukocyte Biology Section, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, United Kingdom; ¶St. Helier Hospital, Carshalton, Surrey SM5 1AA, United Kingdom; ʈCritical Care, Maples Bridge Link, Podium 3, University College London Hospitals National Health Service Foundation Trust, 235 Euston Road, London, NW1 2BU, United Kingdom; and **Centre for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Division of Medicine, 5 University Street, University College London, London WC1E 6JJ, United Kingdom Edited by Charles Serhan, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, and accepted by the Editorial Board October 21, 2007 (received for review August 6, 2007) Hematopoietic prostaglandin D2 synthase (hPGD2S) metabolizes inflammation (6–8). Although controversial, it is believed that 12–14 cyclooxygenase (COX)-derived PGH2 to PGD2 and 15-deoxy⌬ PGD2 is initially converted to PGJ2 and 15-deoxy-PGD2 (15d- PGJ2 (15d-PGJ2). Unlike COX, the role of hPGD2S in host defense is PGD2) in an albumin-independent manner. Thereafter, the cyclo- 12, 14 ambiguous. PGD2 can be either pro- or antiinflammatory depend- pentenone PGs (cyPGs) 15-deoxy-⌬ -PGJ2 (15d-PGJ2) and 12 ing on disease etiology, whereas the existence of 15d-PGJ2 and its ⌬ -PGJ2 are generated from PGJ2 by albumin-independent and relevance to pathophysiology remain controversial.