Knowledge of Obstetric Danger Signs and Associated Factors Among

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Somali Region

Federalism and ethnic conflict in Ethiopia. A comparative study of the Somali and Benishangul-Gumuz regions Adegehe, A.K. Citation Adegehe, A. K. (2009, June 11). Federalism and ethnic conflict in Ethiopia. A comparative study of the Somali and Benishangul-Gumuz regions. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13839 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13839 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). 8 Inter-regional Conflicts: Somali Region 8.1 Introduction The previous chapter examined intra-regional conflicts within the Benishangul-Gumuz region. This and the next chapter (chapter 9) deal with inter-regional conflicts between the study regions and their neighbours. The federal restructuring carried out by dismantling the old unitary structure of the country led to territorial and boundary disputes. Unlike the older federations created by the union of independent units, which among other things have stable boundaries, creating a federation through federal restructuring leads to controversies and in some cases to violent conflicts. In the Ethiopian case, violent conflicts accompany the process of intra-federal boundary making. Inter-regional boundaries that divide the Somali region from its neighbours (Oromia and Afar) are ill defined and there are violent conflicts along these borders. In some cases, resource conflicts involving Somali, Afar and Oromo clans transformed into more protracted boundary and territorial conflicts. As will be discussed in this chapter, inter-regional boundary making also led to the re-examination of ethnic identity. -

Hum Ethio Manitar Opia Rian Re Espons E Fund D

Hum anitarian Response Fund Ethiopia OCHA, 2011 OCHA, 2011 Annual Report 2011 Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Humanitarian Response Fund – Ethiopia Annual Report 2011 Table of Contents Note from the Humanitarian Coordinator ................................................................................................ 2 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 2011 Humanitarian Context ........................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Map - 2011 HRF Supported Projects ............................................................................................. 6 2. Information on Contributors ................................................................................................................ 7 2.1 Donor Contributions to HRF .......................................................................................................... 7 3. Fund Overview .................................................................................................................................... 8 3.1 Summary of HRF Allocations in 2011 ............................................................................................ 8 3.1.1 HRF Allocation by Sector ....................................................................................................... -

Dire Dawa Millennium Park

IOM SITE MANAGEMENT SITE PROFILE - ETHIOPIA, DIRE DAWA SUPPORT Dire Dawa Millennium Park (January 2020) Publication: 01 February 2020 ETHIOPIA IOM OIM Context The residents of Millennium Park IDP site are Somali IDPs who fled their areas of origin in Oromia. The site, which is located on Current Priority Needs land slated for development by the Dire Dawa Municipality, with World Bank funding, is included in the Somali Regional Govern- Site Overview Site Population ment's durable solutions planning, though the timeframe for potential relocations to Somali Region is not yet known. In the interim, many basic humanitarian needs of the site residents are unmet, including safe water provision and sufficient latrine coverage. Fo- 1 WASH Site Location 1,638 individuals od distribution was very irregular in the second half of 2019, but distribution did take place in Jan 2020 2 Livelihood Latitude: 9.6056860 306 households Longitude:41.859980 2 3 Health Site Area: 30,000m Data source: DTM Data, SA 20 of November 2019 Methodology Established in: Sep. 18 2017 * Priority needs as reported by residents through SMS-run Complaint The information for this site profile was collected through key informant interviews and group discussions with the Site Management and Feedback Mechanism Committees and beneficiaries by the Site Management Support (SMS) team in the area. Population figures are collected and aligned through SMS and DTM and allow for the most accurate analysis possible. Sector Overview Demographics Vulnerabilities 0 Unaccompanied children Implementing -

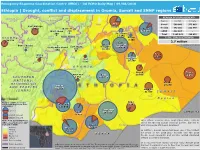

Drought, Conflict and Displacement in Oromia, Somali and SNNP Regions

Emergency Response Coordination Centre (ERCC) – DG ECHO Daily Map | 09/08/2018 Ethiopia | Drought, conflict and displacement in Oromia, Somali and SNNP regions REASON OF DISPLACEMENT* BENSHANGUL- GUMAZ AMAHARA Region Conflict Climate AFAR Siti Somali 500 003 373 663 East Wallega 78 687 Oromia 643 201 112 949 27 672 North Sheva Fafan West Sheva 220 113 593 SNNP 822 187 - 309 Dire Dawa Total 1 965 391 486 612 11 950 Kelem Wellega Harari TOTAL IDPs In ETHIOPIA 24 338 3 605 East 2.7 million West Bunno Bedele Hararghe *Excluding other causes East Sheva Hararghe 2 172 South West Sheva 169 860 180 678 40 030 Jimma Jarar 5 448 49 007 Arsi Erer zone SOMALIA 4 185 36 308 Source: Fews Net OROMIA Nogob Doolo West Arsi Bale 25 659 89 911 S O U T H E R N 4 454 121 772 NATIONS, Korahe NATIONALITIES 24 295 Gedeo A N D PEOPLES 822 187 (SNNP) Shabelle SOUTH 41 536 S O M A L I SUDAN R e g i o n Number of IDPs in Oromia Afder and Somali Region per Zone West Guji 55 963 (July 2018) 147 040 20 000 Dawa zone Guji 244 638 SOMALIA Conflict induced 51 682 Climate induced Source: Fews Net, IOM Acute Food Insecurity Phase Inter-ethnic violence since September 2017, namely DTM Round 11 | Source (IPC’s classification for July– along the Oromia-Somali regional border, has led to for Gedeo and West Guji: September 2018) Liben 500 000 people still being displaced. IOM Situation Report N.1 No Data 114 069 Borena 4-18 July 2018 Minimal 156 110 In addition, Somali region has been one of the hardest Stressed hit areas of the 2016-2017 drought and the 2018 Crisis KENYA floods. -

Women in Conflict and Indigenous Conflict Resolution Among the Issa and Gurgura Clans of Somali in Eastern Ethiopia

Women in conflict and indigenous conflict resolution among the Issa and Gurgura clans of Somali in Eastern Ethiopia Bamlaku Tadesse, Yeneneh Tesfaye and Fekadu Beyene* Abstract This article tries to show the impacts of conflict on women, the role of women in conflict and indigenous conflict resolution, and the participation of women in social institutions and ceremonies among the Issa and Gurgura clans of the Somali ethnic group. It explores the system of conflict resolution in these clans, and women’s representation in the system. The primary role of women in the formation of social capital through marriage and blood relations between different clans or ethnic groups is assessed. The paper focuses on some of the important elements of the socio-cultural settings of the study community that are in one way or another related to conflict and indigenous conflict resolution mechanisms. It also examines the positive aspects of marriage practices in the formation of social capital which strengthens friendship and unity instead of enmity. * Mr Bamlaku Tadesse has an M.A. in Social Anthropology and is Head of the Department of Gender and Development at the Institute of Pastoral and Agro-Pastoral Studies, Haramaya University, Dire-Dawa, Ethiopia. Mr Yeneneh Tesfaye also has an M.A. in Social Anthropology and works in the Department of Rural Development and Agricultural Extension at the College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, Haramaya University. Dr Fekadu Beyene is a Resource Economist and Assistant Professor in the Department of Rural Development and Agricultural Extension, and Director of the Institute of Pastoral and Agro-Pastoral Studies at Haramaya University. -

European Academic Research, Vol III, Issue 3, June 2015 Murty, M

EUROPEAN ACADEMIC RESEARCH Vol. III, Issue 10/ January 2016 Impact Factor: 3.4546 (UIF) ISSN 2286-4822 DRJI Value: 5.9 (B+) www.euacademic.org An Economic Analysis of Djibouti - Ethiopia Railway Project Dr. DIPTI RANJAN MOHAPATRA Associate Professor (Economics) School of Business and Economics Madawalabu University Bale Robe, Ethiopia Abstract: Djibouti – Ethiopia railway project is envisaged as a major export and import connection linking land locked Ethiopia with Djibouti Port in the Red Sea’s international shipping routes. The rail link is of utter significance both to Ethiopia and to Djibouti, as it would not only renovate this tiny African nation into a multimodal transport hub but also will provide competitive advantage over other regional ports. The pre-feasibility study conducted in 2007 emphasized the importance of the renovation of the project from economic and financial angle. However, as a part of GTP of Ethiopia this project has been restored with Chinese intervention. The operation expected in 2016. The proposed project is likely to provide multiple benefits such as time saving, reduction in road maintenance costs, fuel savings, employment generation, reduction in pollution, foreign exchange earnings and revenue generation. These benefits will accrue to government, passengers, general public and to society in nutshell. Here an economic analysis has been carried out to evaluate certain benefits that the project will realize against the cost streams in 25 years. The NPV of the cost streams @ 12% calculated to be 6831.30 million US$. The economic internal rate of return of investments will be 18.90 percent. Key words: EIRR, NPV, economic viability, sensitivity analysis JEL Classification: D6, R4, R42 11376 Dipti Ranjan Mohapatra- An Economic Analysis of Djibouti - Ethiopia Railway Project 1.0 INTRODUCTION: The Djibouti-Ethiopia Railway (Chemin de Fer Djibouti- Ethiopien, or CDE) Project is 784 km railway running from Djibouti to Addis Ababa via Dire Dawa. -

Places of Detention

ICRC The ICRC is present in Ethiopia since the beginning of the 1977 Ethio-Somalia armed conflict. Its current major activities in the country are visiting places of detention so as to ensure both the treatment and conditions of detainees and helping people with physical disabilities (PWDs) get access to quality and sustainable physical rehabilitation services. It also works closely with the Ethiopian Red Cross Society (ERCS) to restore family links among people separated by armed conflict and other situations of violence and provides assistance mainly to people displaced by conflict. The ICRC also promotes the knowledge of International Humanitarian Law (IHL) among members of defense and polices forces as well as higher learning institutions. In 2020, the ICRC’s humanitarian activities mainly focused on responses to two major crises caused by COVID-19 outbreak and fighting in northern Ethiopia. The ICRC had rapidly adapted to the evolving reality of the outbreak of the coronavirus in the country and had stepped up its response to the crisis integrating COVID-19 as an important new parameter in its operations. In response to the humanitarian crisis caused as a result of the fighting in northern Ethiopia since early November, the ICRC had quickly scaled up its response in delivering medicine and medical supplies to health facilities, which were badly affected by shortage of supplies and reconnecting the families with their relatives in Tigray. Moreover, the ICRC and ERCS jointly provided emergency relief and water to the affected communities, including to internally displaced persons. PLACES OF DETENTION From January to December 2020, the ICRC: Visited nearly 72,000 detainees and followed up 242 detainees individually. -

Ethiopia Access Snapshot - Afar Region and Siti Zone, Somali Region As of 31 January 2020

Ethiopia Access Snapshot - Afar region and Siti zone, Somali region As of 31 January 2020 Afar region is highly prone to natural disasters Afdera The operating environment is highly compromised, with a high such as droughts and seasonal flooding. Long-- risk for humanitarian operations of becoming politicized. In ErebtiDalol Zone 2 term historical grievances coupled with Bidu March 2019, four aid workers were detained by Afar authorities TIGRAY resource-based tensions between ethnic Afar for having allegedly entered the region illegally. They were KunnebaBerahile and its neighbors i.e. Issa (Somali), and Oromo Megale conducting a humanitarian activity in Sitti zone, and decided to Teru Ittu (Amibara woreda) and Karayu (Awash Fentale woreda) in ERITREA overnight in a village of Undufo kebele. In a separate incident, in Yalo AFAR Kurri Red Sea October 2019, an attack by unidentified armed men in Afambo zone 3, and in areas adjacent to Oromia special zone and Amhara- Afdera Robe Town Aso s a Ethnic Somali IDPZone 2016/2018 4 Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Elidar region, continue to cause casualties and forced displacement, Aba 'Ala woreda, Zone 1, near Djibouti, killed a number of civilians spark- Gulina Goba Town limiting partners’ movements and operations. Overall, Ethnican Oromia IDP 2016/2018 L. Afrera Ye'ch'ew ing outrage across the region and prompting peaceful demon- Awra estimated 50,000 people remain displaced, the majority of whom Erebti strations and temporarily road blockages of the Awash highway SNNP Zone 1 Bidu rely almost entirely on assistance provided by host communities. Semera TIGRAYEwa On the other hand, in 2019, the overflow of Awash River and DJIBOUTI Clashes involving Afar and Somali Issa clan continue along Megale Afele Kola flash floods displaced some 3,300 households across six Dubti boundary areas between Afar’s zone 1 and 3 and Sitti zone. -

Moving up Or Moving Out? a Rapid Livelihoods and Conflict Analysis in Mieso-Mulu Woreda, Shinile Zone, Somali Region, Ethiopia

A PR I L 2 0 1 0 Strengthening the humanity and dignity of people in crisis through knowledge and practice Moving Up or Moving Out? A Rapid Livelihoods and Conflict Analysis in Mieso-Mulu Woreda, Shinile Zone, Somali Region, Ethiopia Andy Catley and Alula Iyasu ©2010 Feinstein International Center and Mercy Corps. All Rights Reserved. Fair use of this copyrighted material includes its use for non-commercial educational purposes, such as teaching, scholarship, research, criticism, commentary, and news reporting. Unless otherwise noted, those who wish to reproduce text and image files from this publication for such uses may do so without the Feinstein International Center’s express permission. However, all commercial use of this material and/or reproduction that alters its meaning or intent, without the express permission of the Feinstein International Center, is prohibited. Feinstein International Center Tufts University 200 Boston Ave., Suite 4800 Medford, MA 02155 USA tel: +1 617.627.3423 fax: +1 617.627.3428 fic.tufts.edu Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the following Mercy Corps staff who assisted with organisation of the study or who facilitated focus group discussions in Mulu: Mesfin Ayele, Mohammed Haji, Niama Ibrahim, Berhanu Esehete, and Yigezu Solomon. Other Mercy Corps staff provided helpful advice on the design of the work or commented on the draft report, including Abdi Aden, Fasil Demeke, Rafael Velaquez, Nigist Tilahun, and Sarah Gibbons. Demeke Eshete of Save the Children UK provided food economy reports for Shinile Zone. We are also grateful to participants in focus group discussions in Mulu and to the various government staff who provided information and joined the livelihoods analysis training. -

The Nation State a Wrong Model for the Horn of Africa Edition Open Access

The Nation State A Wrong Model for the Horn of Africa Edition Open Access Series Editors Ian T. Baldwin, Gerd Graßhoff, Jürgen Renn, Dagmar Schäfer, Robert Schlögl, Bernard F. Schutz Edition Open Access Development Team Lindy Divarci, Sylvia Szenti, Klaus Thoden The Edition Open Access (EOA) platform was founded to bring together publication ini tiatives seeking to disseminate the results of scholarly work in a format that combines tra ditional publications with the digital medium. It currently hosts the openaccess publica tions of the “Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge” (MPRL) and “Edition Open Sources” (EOS). EOA is open to host other open access initia tives similar in conception and spirit, in accordance with the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the sciences and humanities, which was launched by the Max Planck Society in 2003. By combining the advantages of traditional publications and the digital medium, the platform offers a new way of publishing research and of studying historical topics or current issues in relation to primary materials that are otherwise not easily available. The volumes are available both as printed books and as online open access publications. They are directed at scholars and students of various disciplines, as well as at a broader public interested in how science shapes our world. The Nation State A Wrong Model for the Horn of Africa John Markakis, Günther Schlee, and John Young Studies 14 Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Studies 14 Cover Image: The wrong model: Nation states as islands. -

RESILIENCE in ACTION Drylands CONTENTS

Changing RESILIENCE Horizons in Ethiopia’s IN ACTION Drylands PEOPLE AND COMMUNITIES 3 Changing RESILIENCE Horizons in Ethiopia’s IN ACTION Drylands Changing Horizons in Ethiopia’s RESILIENCE IN ACTION Drylands CONTENTS 4 FOREWORD 6 PEOPLE AND COMMUNITIES 34 LIVESTOCK AND MARKETS 56 PASTURE AND WATER 82 CHANGING HORIZONS 108 USAID’S PARTNERS 112 ABOUT USAID 2 RESILIENCE IN ACTION PASTURE AND WATER 3 FOREWORD MAP OF ETHIOPIA’S DRYLANDS ERITREA National Capital TIGRAY YEMEN Regional Capitals Dry Lands Regional Boundaries SUDAN National Boundary AFAR DJIBOUTI AMHARA BINSHANGUL- GAMUZ SOMALIA OROMIYA GAMBELLA ETHIOPIA SOMALI OROMIYA SOUTH SNNP SUDAN SOMALIA UGANDA KENYA re·sil·ience /ri-zíl-yuh ns/ noun The ability of people, households, communities, countries, and systems to mitigate, adapt to, and recover from shocks and stresses in a manner that reduces chronic vulnerability and facilitates inclusive growth. ETHIOPIA’S enormous pastoral pop- minimized thanks to USAID’s support for commercial Our approach in Ethiopia recognizes these dynamics, giving them better access to more reliable water resources ulation is estimated at 12 to 15 million destocking and supplementary livestock feeding, which working closely with communities while developing and reducing the need to truck in water, a very expensive people, the majority of whom live in supplied fodder to more than 32,000 cattle, sheep, and relationships with new stakeholders, such as small proposition, in future droughts which are occurring at a the arid or semi-arid drylands that goats. In addition, households were able to slaughter the businesses in the private sector (for instance, slaughter- higher frequency than in past decades.