Twixt Ben Nevis and Glencoe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the HIGHLAND COUNCIL the Proposal Is to Establish a Catchment Area for Bun-Sgoil Ghàidhlig Loch Abar, and a Gaelic Medium

THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL The proposal is to establish a catchment area for Bun-sgoil Ghàidhlig Loch Abar, and a Gaelic Medium catchment area for Lochaber High School EDUCATIONAL BENEFITS STATEMENT THIS IS A PROPOSAL PAPER PREPARED IN TERMS OF THE EDUCATION AUTHORITY’S AGREED PROCEDURE TO MEET THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE SCHOOLS (CONSULTATION) (SCOTLAND) ACT 2010 INTRODUCTION The Highland Council is proposing, subject to the outcome of the statutory consultation process: • To establish a catchment area for Bun-sgoil Ghàidhlig Loch Abar. The new Gàidhlig Medium (GM) catchment will overlay the current catchments of Banavie Primary School, Caol Primary School, Inverlochy Primary School, Lundavra Primary School, Roy Bridge Primary School, Spean Bridge Primary School, and St. Bride’s Primary School • To formalise the current arrangements relating to Gàidhlig Medium Education (GME) in related secondary schools, under which the catchment area for Lochaber High School will apply to both Gàidhlig Medium and English Medium education, and under which pupils from the St. Bride’s PS catchment (part of the Kinlochleven Associated School Group) have the right to attend Lochaber High School to access GME, provided they have previously attended Bun-sgoil Ghàidhlig Loch Abar. • Existing primary school catchments for the provision of English Medium education will be unaffected. • The proposed changes, if approved, will be implemented at the conclusion of the statutory consultation process. If implemented as drafted, the proposed catchment for Bun-sgoil Ghàidhlig Loch Abar will include all of the primary school catchments within the Lochaber ASG, except for that of Invergarry Primary School. The distances and travel times to Fort William from locations within the Invergarry catchment make it unlikely that GM provision would be attractive to parents of primary school age children, and dedicated transport from the Invergarry catchment could result in excessive cost being incurred. -

Marcello Mercado in Medias Res

Press Release MARCELLO MERCADO IN MEDIAS RES Paintings, drawings, objects, video art Goethestraße 2-3, 10623 Berlin Entrance B via the courtyard September 3, 2016 - Oktober 26, 2016 Marcello Mercado, Heinrich, Acryl, Bleistift, 2015. Opening: September 2 2016, 7 - 9 pm Courtesy: The artist and Galerie Bernet Bertram, Berlin The artist is present. Gallery Bernet Bertram is pleased to present the upcoming exhibition by Marcello Mercado, featuring several of his paintings, large scale drawings, objects, and video and audio art. Marcello Mercado’s work is research as practice: the artist engages with a culture of experimentation and his work spans a wide range of media of equal importance. Analogue working methods form a vital part of the artist's work, in addition to his use of data string processing, genetic materials and advanced technologies as media, which he engages with playfully as if he were playing a keyboard. He is a poetic artist; both a transformer and seismograph, he bridges gaps between digital and organic worlds. Mercado's canvases in oil, acrylic, and pigment move between the fictitious and the real, the figurative and the abstract. The artist dedicates himself to ethical and philosophical themes in his use of dark and illuminated areas of the image as displayed in his works 'Schwarzes verwundete s Tier 1/2', 'The Location' and 'Schnee', where dominant dark purple and black, or pale blue tones and patches of colour in vibrant magenta open up new perspectives. Mercado works against the light once again in his large scale painting 'Heimatlicht', a work that serves as a memory of his Argentinean roots and resembles a wall spanning mural. -

Report on the Current Position of Poverty and Deprivation in Dumfries and Galloway 2020

Dumfries and Galloway Council Report on the current position of Poverty and Deprivation in Dumfries and Galloway 2020 3 December 2020 1 Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. National Context 2 3. Analysis by the Geographies 5 3.1 Dumfries and Galloway – Geography and Population 5 3.2 Geographies Used for Analysis of Poverty and Deprivation Data 6 4. Overview of Poverty in Dumfries and Galloway 10 4.1 Comparisons with the Crichton Institute Report and Trends over Time 13 5. Poverty at the Local Level 16 5.1 Digital Connectivity 17 5.2 Education and Skills 23 5.3 Employment 29 5.4 Fuel Poverty 44 5.5 Food Poverty 50 5.6 Health and Wellbeing 54 5.7 Housing 57 5.8 Income 67 5.9 Travel and Access to Services 75 5.10 Financial Inclusion 82 5.11 Child Poverty 85 6. Poverty and Protected Characteristics 88 6.1 Age 88 6.2 Disability 91 6.3 Gender Reassignment 93 6.4 Marriage and Civil Partnership 93 6.5 Pregnancy and Maternity 93 6.6 Race 93 6.7 Religion or Belief 101 6.8 Sex 101 6.9 Sexual Orientation 104 6.10 Veterans 105 7. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Poverty in Scotland 107 8. Summary and Conclusions 110 8.1 Overview of Poverty in Dumfries and Galloway 110 8.2 Digital Connectivity 110 8.3 Education and Skills 111 8.4 Employment 111 8.5 Fuel Poverty 112 8.6 Food Poverty 112 8.7 Health and Wellbeing 113 8.8 Housing 113 8.9 Income 113 8.10 Travel and Access to Services 114 8.11 Financial Inclusion 114 8.12 Child Poverty 114 8.13 Change Since 2016 115 8.14 Poverty and Protected Characteristics 116 Appendix 1 – Datazones 117 2 1. -

Parsiųsti Šio Puslapio PDF Versiją

Sveiki atvykę į Lochaber Lochaber'e jūs atrasite tikrąjį natūralųjį Glencoe kalnų grožį kartu ir prekybos centrą Fort Williame, visa tai - vienoje vieoje. Ši vieta garsi kasmet vykstančiomis kalnų dviračių lenktynėmis ir, žinoma, Ben Nevis viršūne - auščiausiu Didžiosios Britanijos tašku. Ties Mallaig kelias į salas daro vingį prie pat jūros, tad kelionė Šiaurės-vakarų geležinkelio linija iš Glazgo palieka nepakartojamą ir išbaigtą gamtos grožio įspūdį. Nekyla abejonių, kodėl Lochaber yra žinomas kaip Britanijos gamtovaizdžių sostinė. Lochaber išleido savo informacinį leidinį migruojantiems darbininkams. Jį galima surasti lenkų ir latvių kalbomis Lochaber Enterprise tinklapyje. Vietinis Piliečių patarimų biuras Lochaber Citizens Advice Bureau Dudley Road Fort William PH33 6JB Tel: 01397 – 705311 Fax: 01397 – 700610 Email: [email protected] Darbo laikas: Pirmadienis, antradienis, ketvirtadienis, penktadienis10.00 – 14.00 trečiadienis 10.00 – 18.00 savaitgaliais nedirba. Įdomu: Žvejo misija Mallaig 1as mėnesio trečiadienis10.30 – 15.30 Pramogų kompleksai ir baseinai Lochaber Leisure Centre Belford Road Fort William PH33 6BU Tel: 01397 707254 Vadybininkas: Graham Brooks Mallaig Swimming Pool Fank Brae Mallaig PH41 4RQ Tel: 01687 462229 http://www.mallaigswimmingpool.co.uk/ Arainn Shuaineirt (No Swimming Pool) Ardnamurchan High School Strontian PH36 4JA Tel: 01397 709228 Vadybininkas: Eoghan Carmichael Nevis Centre (No Swimming Pool) An Aird Fort William PH33 6AN Tel: 01397 700707 Bibliotekos Ardnamurchan / Caol / Fort William / Kinlochleven / Knoydart / Mallaig Ardnamurchan Community Library Sunart Centre Strontian Acharacle PH36 4JA Tel/Fax: 01397 709226 e-mail: [email protected] Darbo laikas: Pirmadienis 09.00 – 16.00 Antradienis 09.00 – 16.00, 19.00 – 21.00 Trečiadienis 09.00 – 16.00 Ketvirtadienis 09.00 – 16.00, 19.00 – 21.00 Penktadienis 09.00 – 16.00 Šeštadinis 14.00 – 16.00 Caol Library Glenkingie Street, Caol, Fort William, Lochaber, PH33 7DP. -

Population Change in Lochaber 2001 to 2011

The Highland Council Agenda 5 Item Lochaber Area Committee Report LA/2/14 No 27 February 2014 Population Change in Lochaber 2001 To 2011 Report by Director of Planning and Development Summary This report presents early results from the 2011 Census, giving local information on the number and ages of people living within Lochaber. It compares these figures with those from 2001 to show that the population has “aged”, and that there is a large number of people who are close to retirement age. The population of Lochaber has grown by 6.1% (compared to the Highland average of 11.1%) with an increase in both Wards, and at a local level in 18 out of 27 data zones. Local population growth is strongly linked to the building of new homes. 1. Background 1.1. Publication of the results from the 2011 Census began in December 2012, and the most recent published in November and December 2013 gave the first detailed results for “census output areas”, the smallest areas for which results are published. These detailed results have enabled preparation of the first 2011 Census profiles and these are available for Wards, Associated School Groups, Community Councils and Settlement Zones on the Highland Council’s website at: http://www.highland.gov.uk/yourcouncil/highlandfactsandfigures/census2011.htm 1.2. This report returns to some earlier results and looks at how the age profile of the Lochaber population and the total numbers have changed at a local level (datazones). The changes for Highland are summarised in Briefing Note 57 which is attached at Appendix 1. -

2019 Scotch Whisky

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

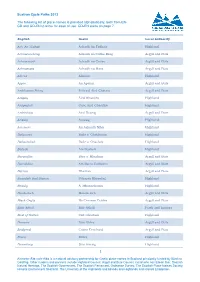

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013 The following list of place-names is provided alphabetically, both from EN- GD and GD-EN to allow for ease of use. GD-EN starts on page 7. English Gaelic Local Authority Ach' An Todhair Achadh An Todhair Highland Achnacreebeag Achadh na Crithe Beag Argyll and Bute Achnacroish Achadh na Croise Argyll and Bute Achnamara Achadh na Mara Argyll and Bute Alness Alanais Highland Appin An Apainn Argyll and Bute Ardchattan Priory Priòraid Àird Chatain Argyll and Bute Ardgay Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardgayhill Cnoc Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardrishaig Àird Driseig Argyll and Bute Arisaig Àrasaig Highland Aviemore An Aghaidh Mhòr Highland Balgowan Baile a' Ghobhainn Highland Ballachulish Baile a' Chaolais Highland Balloch Am Bealach Highland Baravullin Bàrr a' Mhuilinn Argyll and Bute Barcaldine Am Barra Calltainn Argyll and Bute Barran Bharran Argyll and Bute Beasdale Rail Station Stèisean Bhiasdail Highland Beauly A' Mhanachainn Highland Benderloch Meadarloch Argyll and Bute Black Crofts Na Croitean Dubha Argyll and Bute Blair Atholl Blàr Athall Perth and kinross Boat of Garten Coit Ghartain Highland Bonawe Bun Obha Argyll and Bute Bridgend Ceann Drochaid Argyll and Bute Brora Brùra Highland Bunarkaig Bun Airceig Highland 1 Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba is a national advisory partnership for Gaelic place-names in Scotland principally funded by Bòrd na Gaidhlig. Other funders and partners include Highland Council, Argyll and Bute Council, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, Scottish Natural Heritage, The Scottish Government, The Scottish Parliament, Ordnance Survey, The Scottish Place-Names Society, Historic Environment Scotland, The University of the Highlands and Islands and Highlands and Islands Enterprise. -

No. Forename Surname Club / Organisation Distance 123 Stuart

No. Forename Surname Club / Organisation Distance 123 Stuart ADAMSON Stewartry Wheelers 100 miles 147 Charlie ALEXANDER Hillhead Raiders CC 100 miles 148 Matt ANDERSON None 62miles 51 John ANDREW Dumfries CC 100 miles 266 David ARTHUR Athelite Triathlon Club 100 miles 12 Steven ASHWORTH None 100 miles 149 Alan AULD Strathclyde Police 100 miles 150 Simon BAIN Glasgow Green Cycling Club 100 miles 139 Andrew BAIRD West Lothian Clarion 100 miles 151 Stuart BARR None 100 miles 102 Mary BARRETT SSCC 100 miles 153 Stewart BECK None 100 miles 63 David BELDING Walkers CC 100 miles 154 Steven BELL None 100 miles 155 Ian BELL None 100 miles 27 Michael BETHWAITE Honister 92 100 miles 285 Andy Blackett None 62miles 70 Gordon BONALLO West Lothian Clarion 100 miles 157 Leon BOND Honister 92 100 miles 158 Alan BOWIE None 62miles 159 Allan BOYD None 100 miles 160 Brian BOYD None 62miles 161 Raymond BOYD None 100 miles 162 Hugh BOYLE None 100 miles 8 Anna BROOKS Morningside medical practice 62miles 163 Chris BROWN None 100 miles 164 Stephen BROWN None 100 miles 165 Ian BROWN None 100 miles 304 Drew BRUNTON None 100 miles 250 Dawn BUCHANAN Athelite Triathlon Club 100 miles 168 Pat BURNS None 100 miles 169 Kevin BURNS None 100 miles 170 Peter Burtwistle Royal Albert Cycling Club 100 miles 92 Lorne CALLAGHAN West Lothian Clarion 100 miles 20 Ewan CAMPBELL ??? 172 Barry CAMPBELL None 100 miles 174 Iain CAMPBELL None 100 miles 79 Jacqui CARRICK HERVELO 62miles 80 Nigel CARRICK Kelso Wheelers 100 miles 176 Derek CARRIGAN None 100 miles 179 Malcolm CARSON None -

READING POUND : SEVEN 1. So That the Vines Burst from My Fingers and the Bees Weighted with Pollen Move Heavily in the Vine-Sho

READING POUND : SEVEN 1. So that the vines burst from my fingers And the bees weighted with pollen Move heavily in the vine-shoots: chirr--chirr--chir-rikk--a purring sound, And the birds sleepily in the branches. ZAGREUS! IO ZAGREUS! With the first pale-clear of the heaven And the cities set in their hills, And the goddess of the fair knees Moving there, with the oak-wood behind her, The green slope, with the white hounds leaping about her; And thence down to the creek's mouth, until evening, Flat water before me, and the trees growing in water, Marble trunks out of stillness, On past the palazzi, in the stillness, The light now, not of the sun. Chrysophrase, And the water green clear, and blue clear; On, to the great cliffs of amber. Between them, Cave of Nerea, she like a great shell curved, And the boat drawn without sound, Without odour of ship-work, Nor bird-cry, nor any noise of wave moving, Within her cave, Nerea, she like a great shell curved In the suavity of the rock, cliff green-gray in the far, In the near, the gate-cliffs of amber, And the wave green clear, and blue clear, And the cave salt-white, and glare-purple, cool, porphyry smooth, the rock sea-worn. No gull-cry, no sound of porpoise, Sand as of malachite, and no cold there, the light not of the sun. Zagreus, feeding his panthers, the turf clear as on hills under light. And under the almond-trees, gods, with them, choros nympharum. -

THE GLENLOY WOODLANDS Near Fort William, Lochaber 228.72 Hectares / 565.16 Acres

THE GLENLOY WOODLANDS Near Fort William, Lochaber 228.72 Hectares / 565.16 Acres John Clegg & Co CHARTERED SURVEYORS & FORESTRY AGENTS THE GLENLOY WOODLANDS Fort William 11 miles Inverness 64 miles Perth 109 miles Edinburgh 153 miles (Distances are approximate) THE GLENLOY WOODLANDS 228.72 Hectares / 565.16 Acres Two areas of mixed species commercial woodland with a substantial volume of mature timber ready for felling. Stunning location in a highly scenic area, close to Fort William and Timber Markets. FREEHOLD FOR SALE AS A WHOLE OFFERS OVER £950,000 SOLE SELLING AGENTS John Clegg & Co, 2 Rutland Square, Edinburgh EH1 2AS Tel: 0131 229 8800 Fax: 0131 229 4827 Ref: Patrick Porteous 10/05/2017 15:19 LOCATION LOCATION The Glenloy Woodlands are situated in Glenloy, approximately A recent volume estimate from plot sampling has been carried Further information, including compartment data, maps The Glenloy Woodlands are situated in Glenloy, approximately A recent volume estimate from plot sampling has been carried Further information, including compartment data, maps 11 miles north of Fort William. This is a stunning and secluded out within the two woodlands. The combined stocked area of 11 miles north of Fort William. This is a stunning and secluded out within the two woodlands. The combined stocked area of andand volumevolume measurementmeasurement data data is is available available from from the the Selling Selling part of the country, yet it is very accessible to Fort William and conifer amounts to approximately 219.10 hectares, which is part of the country, yet it is very accessible to Fort William and conifer amounts to approximately 219.10 hectares, which is AgentsAgents uponupon request.request. -

The Lowland Clearances and Improvement in Scotland

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses August 2015 Uncovering and Recovering Cleared Galloway: The Lowland Clearances and Improvement in Scotland Christine B. Anderson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Christine B., "Uncovering and Recovering Cleared Galloway: The Lowland Clearances and Improvement in Scotland" (2015). Doctoral Dissertations. 342. https://doi.org/10.7275/6944753.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/342 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Uncovering and Recovering Cleared Galloway: The Lowland Clearances and Improvement in Scotland A dissertation presented by CHRISTINE BROUGHTON ANDERSON Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2015 Anthropology ©Copyright by Christine Broughton Anderson 2015 All Rights Reserved Uncovering and Recovering Cleared Galloway: The Lowland Clearances and Improvement in Scotland A Dissertation Presented By Christine Broughton Anderson Approved as to style and content by: H Martin Wobst, Chair Elizabeth Krause. Member Amy Gazin‐Schwartz, Member Robert Paynter, Member David Glassberg, Member Thomas Leatherman, Department Head, Anthropology DEDICATION To my parents. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is with a sense of melancholy that I write my acknowledgements. Neither my mother nor my father will get to celebrate this accomplishment. -

Health and Social Care NITHSDALE LOCALITY REPORT March 2021

Dumfries and Galloway Integration Joint Board Health and Social Care NITHSDALE LOCALITY REPORT March 2021 Version: DRAFT March 2021 1. General Manager’s Introduction 1.1 The COVID-19 Pandemic The past year has presented unprecedented challenges for health and social care across Dumfries and Galloway. The first 2 cases of COVID-19 in the UK were confirmed by 31 January 2020. The first positive cases in Dumfries and Galloway were identified on 16 March 2020. Following direction from the Scottish Government, in March 2020 Dumfries and Galloway Health and Social Care Partnership started their emergency response to the pandemic. Hospital wards were emptied and some cottage hospitals temporarily closed. Many planned services were stopped whilst others changed their delivery model. Many staff were redeployed to assist with anticipated high levels of demand across the Partnership. There were many issues that had to be addressed including: the supply and distribution of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) across the Health and Social Care system over 500 people’s regular care and support ‘packages’ were readjusted to respond to the needs presented by COVID-19 our relationships with care homes changed significantly we quickly kitted out a site that could be used as a temporary cottage hospital in Dumfries During the period of June to October 2020, the Partnership focused on adapting services to reflect the heightened infection prevention and control measures needed to combat COVID-19 and rapidly expanding COVID-19 testing capacity across the region. We rolled out training and technology to enable many more video and telephone consultations. We had to rethink how people could access our premises, with additional cleaning and social distancing to keep people safe.