The History of English Podcast Transcripts Episodes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Canonization of William Wallace?

CLAN WALLACE SOCIETY WORLDWIDE Am fear-gléidhidh “The Guardian”— Published Quarterly by the Clan Wallace Society Worldwide. Founded 1966. Spring/Summer 2002 Vol 36, No 1 New Members From the President’s Desk On behalf of Ian Francis Wallace of that Ilk, This winter/spring your President represented At my last count, the Society has 888 35th Chief of Clan Wallace, the President and the Clan Wallace Society, criss-crossing the members. Recruiting has been very good this Board of Directors of the Clan Wallace Society United States, from Moutrie (GA) to Mesa past year, placing us well within reach of our Worldwide welcome the FORTY-SEVEN indi- (AZ) and most games in between. goal of 1,000 members. Several new viduals listed below to the Clan Council and to convenors have taken their places, but usual, The weekend in Moutrie was somewhat un- our Society, respectively. Ciad mile failte! more are needed to maintain the pace. As usual in that this is not a Scottish Games and well, several key convenors have retired after Gathering but rather a Scottish Family Gath- COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP: many years or due to health problems. With ering with emphasis on family histories. This Clinton H. Wallace, Beverly Hills, CA the new season starting up, please consider annual weekend was sponsored by The Fam- Murray C. Walker, Silver Springs, MD at least doing the games closest to your ily Tree Magazine and the Ellen Payne Odem Ilie Leonard Wallace, Linwood, NJ home. You can get people more involved with Library. You will find an article outlining how Harry E. -

Phases of Irish History

¥St& ;»T»-:.w XI B R.AFLY OF THE UNIVERSITY or ILLINOIS ROLAND M. SMITH IRISH LITERATURE 941.5 M23p 1920 ^M&ii. t^Ht (ff'Vj 65^-57" : i<-\ * .' <r The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its return on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for disciplinary action and may result in dismissal from the University. University of Illinois Library • r m \'m^'^ NOV 16 19 n mR2 51 Y3? MAR 0*1 1992 L161—O-1096 PHASES OF IRISH HISTORY ^.-.i»*i:; PHASES OF IRISH HISTORY BY EOIN MacNEILL Professor of Ancient Irish History in the National University of Ireland M. H. GILL & SON, LTD. so UPPER O'CONNELL STREET, DUBLIN 1920 Printed and Bound in Ireland by :: :: M. H. Gill &> Son, • • « • T 4fl • • • JO Upper O'Connell Street :: :: Dttblin First Edition 1919 Second Impression 1920 CONTENTS PACE Foreword vi i II. The Ancient Irish a Celtic People. II. The Celtic Colonisation of Ireland and Britain . • • • 3^ . 6i III. The Pre-Celtic Inhabitants of Ireland IV. The Five Fifths of Ireland . 98 V. Greek and Latin Writers on Pre-Christian Ireland . • '33 VI. Introduction of Christianity and Letters 161 VII. The Irish Kingdom in Scotland . 194 VIII. Ireland's Golden Age . 222 IX. The Struggle with the Norsemen . 249 X. Medieval Irish Institutions. • 274 XI. The Norman Conquest * . 300 XII. The Irish Rally • 323 . Index . 357 m- FOREWORD The twelve chapters in this volume, delivered as lectures before public audiences in Dublin, make no pretence to form a full course of Irish history for any period. -

Things Scottish Blackwell’S Rare Books 48-51 Broad Street, Oxford, OX1 3BQ

Blackwell’s Rare Books things scottish Blackwell’s Rare Books 48-51 Broad Street, Oxford, OX1 3BQ Direct Telephone: +44 (0) 1865 333555 Switchboard: +44 (0) 1865 792792 Email: [email protected] Fax: +44 (0) 1865 794143 www.blackwells.co.uk/rarebooks Our premises are on the second floor of the main Blackwell’s bookshop at 48-51 Broad Street, one of the largest and best known in the world, housing over 200,000 new book titles, covering every subject, discipline and interest. The bookshop is in the centre of the city, opposite the Bodleian Library and Sheldonian Theatre, and next door to the Weston Library, with on street parking close by. Hours: Monday–Saturday 9am to 6pm. (Tuesday 9:30am to 6pm.) Our website contains listings of our stock with full descriptions and photographs, along with links to PDF copies of previous catalogues, and full details for contacting us with enquiries about buying or selling rare books. All books subject to prior sale. Staff Andrew Hunter - Antiquarian, Sciences. Email: [email protected] Henry Gott - Modern First Editions, Private Press & Illustrated Books. Email: [email protected] Sian Wainwright - General, Music, Travel. Email: [email protected] Susan Theobald - Photography and catalogue design. Email: [email protected] Front cover illustration: 42 Rear cover illustration: 12 1. (Agriculture. Ireland.) THE DUBLIN SOCIETY’S WEEKLY OBSERVATIONS for the Advancement of Agriculture and Manufactures. Glasgow: Printed and Sold by Robert & Andrew Foulis, 1756, -

Genre and Identity in British and Irish National Histories, 1541-1691

“NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 A dissertation presented by Sarah Elizabeth Connell to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2014 1 “NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 by Sarah Elizabeth Connell ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2014 2 ABSTRACT In this project, I build on the scholarship that has challenged the historiographic revolution model to question the valorization of the early modern humanist narrative history’s sophistication and historiographic advancement in direct relation to its concerted efforts to shed the purportedly pious, credulous, and naïve materials and methods of medieval history. As I demonstrate, the methodologies available to early modern historians, many of which were developed by medieval chroniclers, were extraordinary flexible, able to meet a large number of scholarly and political needs. I argue that many early modern historians worked with medieval texts and genres not because they had yet to learn more sophisticated models for representing the past, but rather because one of the most effective ways that these writers dealt with the political and religious exigencies of their times was by adapting the practices, genres, and materials of medieval history. I demonstrate that the early modern national history was capable of supporting multiple genres and reading modes; in fact, many of these histories reflect their authors’ conviction that authentic past narratives required genres with varying levels of facticity. -

NHB Regional Bowl a JV Round #9

NHB Regional Bowl A JV Round 9 First Quarter 1. One of this author's characters learns the story of Annie Tyler and Who Flung. In that work, one character dies after the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane. The discovery of this author’s grave was described in a magazine article by Alice Walker. For 10 points, name this author of a novel about Tea Cake and Janie Crawford called Their Eyes Were Watching God. ANSWER: Zora Neale Hurston 023-11-60-09101 2. The first member of this house passed the title Lord of Annandale to his descendants. Edward of Balliol advanced on the forces of David II, who was a member of this house. The hero of the Battle of Bannockburn who signed the Treaty of Northampton with England was a member of this house. For 10 points, name this royal house that includes Robert I of Scotland. ANSWER: Bruce family [or House of Bruce; or Clan Bruce] 124-11-60-09102 3. This leader founded the League of Oppressed Peoples and worked for the anti-French underground. This leader's General Giap tricked the French at the siege of Dien Bien Phu. The Seventeenth Parallel divided this leader's country. This leader launched the Tet Offensive and was supported by the Viet Cong. For 10 points, name this Vietnamese communist Leader. ANSWER: Ho Chi Minh [or Nguyen Sinh Cung; or Nguyen Tat Thanh; or Nguyen Ai Quoc] 124-11-60-09103 4. Settlers arrived at this colony on the Susan Constant and Godspeed under Christopher Newport, although many died during the "Starving Time." This colony was the first site of the House of Burgesses. -

Let Have a Look Saint Fhaolain

MacLellan / mac Gille Faelan / son of the Servant of little Wolf Return to Page 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Right click on Url’s, left click open in “new tab”. But not on Return to Page numbers. Let have a look Saint Fhaolain. Of Mac/Mc/M/. Male Meaning Anglicized Wife Daughter Mac son (of) Mac/Mc/M’ Mhic Nic O/Ua grandson (of) O' Uí Ni Fillan, son of Feriach and St. Kentigerna, was also Fhaolain who became a Saint, he would be Naomh Fhaolain, "remembering he was not a saint when he was living", and he died 9th January 777, (Julian Calendar); which is the 20th of January (Gregorian Calendar). (here a story of Naomh Faolan told in Gaidhlig) If he had a son, he would be, mac Fhaolain, his wife would be mich’Fhaolain and his daughter would be nic’Fhaolain. If Saint Fhaolain had servants/followers, they would be Gille Fhaolain or Maol Fhaolain If this devotee had a son, he would be mac’Gille Fhaolain or mac'ill Fhaolain His wife would be called mhic'ill'Fhaolain, and the daughter would be nic'ill'Fhaolain What would the son of mac'ill'Fhaolain be called? The cults of St Fillan served an important function far beyond the significance of the man himself. Perhaps, because of his association with King Robert the Bruce, although it is understood that he had united, through religion the two great power centers of Scotland, the Scots and the Picts, and he was therefore of central importance to the establishment of Scotland as a nation. -

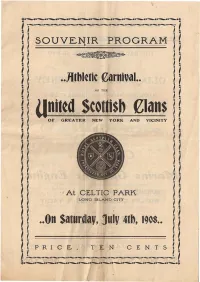

I~ Unittdscottish~Ians ~ ~ Ii

~.~~~~~~.~,......••~.--...•.-.- ••~••~.~'! ; ~--_..........---~-_._-_._---: I • ~ t • I!SOUVE.!'{IR PROGRAM II i~ ~ H il ••Jlbl·t l~tlC ~arU1"afl . I.. I11t 11 OF T HE I i q . l ~ I~ Unittd Scottish~Ians ~ ~ t l . OF GREATER NEW YORK AND VICINITY l i • I ; ~ t l t t • l I . til t iI ; t lit t ill i i'l ~ • I · .r At CEL TIC PARK I t II LONG I SL AN D CITY l t. i I ' H l ~ .•OnSaturday, ]uly4tb,1908.. ~ l tit t I ~ P RIC ' E.. T E. NCENT S ~ t i·_.~-.-.-.-.. _.-.-.-.._.~.~.~.._..~-. t +-~..~.~~ ,, ~........--~..~.-.-..----..,......••-......-... ....--...+ The 'De Lu.xe o/, Scotch Whi ...!(ey • THE BAILlE - NICOL JARVIE BLEND OF = OL D SCOTCH WHISKEY = N COL ANDERSON & CO ., Limited, Glasgow Sole 'Proprietor-s Ca ll be had at the Wa ldorf, Del mon ico's, Cafe Martin and Cafe Lafayette CR... .AIG ... Marine Ga:.s-olineEngine.s- BUILDER. OF TtilE . .... WOR.LD'S GR.EATEST MOTOR. YACHT • AILSA CRAIG JAMES C'R A IG 556 West -34th Street New York 2 COMMI TTEES GENERAL GAME S COMMITT EE Pa st Chief Bryce Martin, Clan MacDonald, No. 33, Chairman Past Chief Charles Patte rson, Clan MacDuff, No. 81, Vice-Chairman Past Chief William Da vidson, Clan MacDouald , No. 33, Secretary Clansman F enwick W. Rit chie, Clan MacDonald, No. 33, Assistant Secretary Pa st Royal Deputy W . B. Simpson, Clan MacKenzie, No. 29, Tr easurer Clansman J ohn Kirk, Clan MacKenzie, No . 29 Pa st Chief David Warnock, Clan MacKenzie,No. 29 Clansman Henry Dunn, Clan MacKenzie, No. -

A Letter from Ireland

A Letter from Ireland Mike Collins lives just outside Cork City, Ireland. He travels around the island of Ireland with his wife, Carina, taking pictures and listening to stories about families, names and places. He and Carina blog about these stories and their travels at: www.YourIrishHeritage.com A Letter from Ireland Irish Surnames, Counties, Culture and Travel Mike Collins Your Irish Heritage First published 2014 by Your Irish Heritage Email: [email protected] Website: www.youririshheritage.com © Mike Collins 2014 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilised in any form or any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or in any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. All quotations have been reproduced with original spelling and punctuation. All errors are the author’s own. ISBN: 978-1499534313 PICTURE CREDITS All Photographs and Illustrative materials are the authors own. DESIGN Cover design by Ian Armstrong, Onevision Media Your Irish Heritage Old Abbey Waterfall, Cork, Ireland DEDICATION This book is dedicated to Carina, Evan and Rosaleen— my own Irish Heritage—and the thousands of readers of Your Irish Heritage who make the journey so wonderfully worthwhile. Contents Preface ...................................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................ 4 Section 1: Your Irish Surname ....................................... -

What's in a Name Cover√

What's In A Name? From Set & Link 2005 ~ 2018 © 2005-2020, RSCDS Toronto Excerpts from these stories may be freely used, with attribution to the author and RSCDS Toronto WHAT’S IN A NAME? The Barry Pipes Canon • 2005 - 2018 From Set&Link, newsletter of RSCDS Toronto Barry Pipes: Resident Contributor by Marie Anne Millar Barry’s first article was about the Mountain of Schiehallion, based on the Schiehallion reels that appear in several dances As a boy in Britain, Barry Pipes was keenly interested in history and and that are named alter the prominent mountain in Perth and geography. He currently uses these interests when writing “WHAT’S IN A Kinross. He writes an article each month for Set & Link; his NAME?” for Set & Link. Inverneill House began with a “For Sale” notice on the house, His intent is simple — write a light, whimsical column explaining the found during his research. names, places, and backgrounds of some Scottish country dances we He says, “One piece I enjoyed writing was about Cutty Sark, know and love. “I start with a particular dance, often from the and I even learned something new and a bit risqué from my programme for a forthcoming SCD event, such as the monthly dance.” Marie Anne Millar research”. He knew the Cutty Sark was a famous clipper ship. He He generates the articles using his own resources on history and Barry Pipes knew it was a Scotch. But he didn’t know it was an undergarment mentioned in the geography, assisted by Google. He has other sources, too. -

Kingship, Lordship, and Resistance: a Study of Power in Eleventh- and Twelfth-Century Ireland

Trinity College, Dublin School of Histories and Humanities Department of History Kingship, lordship, and resistance: a study of power in eleventh- and twelfth-century Ireland Ronan Joseph Mulhaire Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (2020) Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the Library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. _______________________ RONAN MULHAIRE 2 Summary This thesis starts from the premise that historians of medieval Ireland have interpreted ‘power’ in a very narrow way. As chapter one illustrates, through a review of the historiography of Irish kingship, the discussion of ‘power’ has, hitherto, amounted to a conversation about the ways in which the power of the greater Irish kings grew over the course of the eleventh and twelfth centuries (at the expense of the lesser kings). Engaging with the rich corpus of international literature on power, as is done in chapter one, reveals the sheer complexity and vicissitudes of ‘power’ as a concept. Many writers and thinkers on the subject have identified resistance as a means through which to view power relations, and it is along these lines that the rest of the thesis runs. Chapters three and four are concerned with the subject of resistance; with regicide and revolt, respectively. Both mine the Irish annals. -

50 Anniversary

TheThe American-ScottishAmerican-Scottish FoundationFoundation ® 5050 ththAnniversaryAnniversary && ® WallaceWallace AwardAward GalaGala DinnerDinner TheThe UniversityUniversity Club,Club, NewNew YorkYork City,City, OctoberOctober 23,23, 20062006 Walkers Shortbread Congratulates the American Scottish Foundation on their 50th Anniversary. Visit our website to learn more about Walkers Shortbread: www.walkersus.com Baked fresh in our family bakery in the Scottish highlands. FREE shipping on orders over $20. Enter code ASF at checkout. Walkers Deliciously pure. Purely delicious. www.walkersus.com Gala Program wp Cocktail Reception Welcome Presentation of Wallace Award® to Euan Baird Dinner Live Auction Dessert Anniversary Toast 8 1 Mr Alan L Bain October 2006 President The American-Scottish Foundation Inc Scotland House 575 Madison Avenue, Suite 1006 New York NY 100022-2511 USA Dear Mr. Bain, I am delighted to add my congratulations to the American-Scottish Foundation on its 50th anniversary dinner. The American-Scottish Foundation has made a significant contribution to raising the awareness of both traditional and contemporary Scotland in the United States. The Foundation has helped to make Tartan Week become the most successful promotion of Scotland overseas and its involvement in larger initiatives, such as the Scottish Coalition, has been of great benefit to Scotland. I have had the pleasure of meeting many members of the American-Scottish Foundation during my time as First Minister, and I am sorry that I cannot be there to celebrate -

The Demise of an Irish Clan Terence Kearey

61 pages 17,611 words Irish Clan History Lord of Car bury Setting the Scene In ancient Irish times, if you wished to survive interclan strife and usurping raiders, it was sensible to live inland – away from navigational rivers… To live up in the hills on barren land, was also opportune. If you preferred to be quiet, frugal - conserve what you had, it was best to keep away from neighbours – their: borders, boundaries and frontiers, especially those of the king. In addition, even if you did all that, it was still not quite enough, for you needed to be wily and shrewd as well. The O′Ciardha [O′Kearey] land bordered Lough Derg and the River Shannon’s southern shore – its feeder river. The land included loch- side and lowland grassland and upland mineral bearing hills - all in today’s northern Tipperary County. The neighbours to the west were the O′Carrolls and to the east, the O′Kennedys… all boxed in by the O ′Meara - to the south. Follow a line… up the river Shannon round King’s County then across to Dublin, you separate Ireland roughly in half – lands of the southern and northern O′Neill’s. The Gælic-Irish suzerainty employed a form of guarantee based on pledges made during times of strife and war – if you help me out, I will do the same for you. It was not possible in that society to run a clan - group of families with a common ancestor, without seeking help to drive off a Viking raider or cattle rustling neighbour - given that you lived within striking distance of a good beaching area of sea or river, and you held a herd of cattle.