The Good News About Gas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Substitute Natural Gas from Biomass Gasification

Rapport SGC 187 Substitute natural gas from biomass gasification ©Svenskt Gastekniskt Center – mars 2008 Haldor Topsoe's methanation process TREMP Per Tunå, Lund Institute of Technology Rapport SGC 187 •1102-7371 • ISRN SGC-R-187-SE SGC:s FÖRORD FUD-projekt inom Svenskt Gastekniskt Center AB avrapporteras normalt i rapporter som är fritt tillgängliga för envar intresserad. SGC svarar för utgivningen av rapporterna medan uppdragstagarna för respek- tive projekt eller rapportförfattarna svarar för rapporternas innehåll. Den som utnyttjar eventuella beskrivningar, resultat eller dylikt i rapporterna gör detta helt på eget ansvar. Delar av rapport får återges med angivande av källan. En förteckning över hittills utgivna SGC-rapporter finns på SGC:s hemsida www.sgc.se. Svenskt Gastekniskt Center AB (SGC) är ett samarbetsorgan för företag verk- samma inom energigasområdet. Dess främsta uppgift är att samordna och effektivisera intressenternas insatser inom områdena forskning, utveckling och demonstration (FUD). SGC har följande delägare: Svenska Gasföreningen, E.ON Gas Sverige AB, E.ON Sverige AB, Göteborg Energi AB, Lunds Energikoncernen AB (publ) och Öresundskraft AB. Följande parter har gjort det möjligt att genomföra detta utvecklingsprojekt: E.ON Gas Sverige AB Göteborg Energi AB SVENSKT GASTEKNISKT CENTER AB Jörgen Held Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following people for their support throughout this thesis work. Professor Hans T. Karlsson at the Department of Chemical Engineering for his dedication to find an interesting thesis work for me. Christian Hulteberg at the Department of Chemical Engineering as he always has a good answer for everything and always had time to help me. Owe Jönsson at E.ON Gas Sverige AB and Lars A Andersson at Göteborg Energi AB for taking their time and to give valuable suggestions and ideas. -

Maximising the Value of Surplus Ethane and Cost-Effective Design to Handle Rich Lng

Poster PO-25 MAXIMISING THE VALUE OF SURPLUS ETHANE AND COST-EFFECTIVE DESIGN TO HANDLE RICH LNG CC Yang Process and Technology Director, LNG Foster Wheeler USA, 2020 Dairy Ashford, Houston, TX 77077, USA [email protected] Geoffrey Bothamley Business Development Manager Oil and Gas Foster Wheeler Energy Limited, Shinfield Park, Reading, Berkshire, RG2 9FW, UK [email protected] ABSTRACT Gas companies have strict requirements for the composition of the natural gas sent out from their LNG receiving terminals in order to satisfy customer requirements in terms of calorific value and quality of the composition. For LNG receiving terminals serving the North American market particularly, the C2+ content and heating value specifications are lower than most natural gases and most existing LNG baseload plants. Cost-effective management of these components enhances the LNG value chain, increasing flexibility in sourcing LNG cargoes. Several alternatives for managing C2+ components in the LNG value chain exist. Generally, extraction can occur at either the receiving terminal or upstream of the liquefaction plant. In many cases it is not cost-effective to reduce the C2 at the baseload plant, as it will reduce the LNG production rate and there may be no local market. Some LNG production plant locations, however, have grown to a size that would meet minimum economic scale for a steam cracker taking C2 and C3 as feedstock for ethylene and propylene production. To accept cargoes of rich LNG, the LNG receiving terminal has to be able to manage the C2+ components in an economically efficient manner. This paper presents a cost- effective C2+ management process design for send-out gas at the LNG receiving terminal. -

The Future Role of Gas in Transport

The Future Role of Gas in Transport Green Gas Transport Pathway 2 Green Gas Transport Pathways Acknowledgements A Network Innovation Allowance project report for Cadent, Gas Networks Ireland, National Grid, Northern Gas Networks, SGN, Wales and West Utilities Green Gas Transport Pathways 3 Executive Summary Project Background, Aims and Objectives This is a Network Innovation Allowance funded project Green gases overseen by a steering group comprising the UK and Ireland gas network operators (Cadent, Gas Networks Ireland, This report discusses the future role of ‘green gases’ which National Grid, Northern Gas Networks, SGN, Wales and West). are biomethane and hydrogen produced from low- and The project follows on from previous studies1 that modelled zero-carbon sources, each produced via two main methods: the role of green gases in decarbonising the GB economy. The Biomethane from Anaerobic Digestion (AD): A role of this study is to understand the transition from the GB mature technology for turning biological material into economy today to a decarbonised economy in 2050, focusing a non-fossil form of natural gas (methane). AD plants on how the transition is achieved and the competing and produce biogas which must then be upgraded to biomethane. complementary nature of different low and zero emission fuels and technologies over time. Biomethane from Bio-Substitute Natural Gas (Bio-SNG): This technology is at an earlier stage of While the project covers the whole economy it focuses on development than AD, but has the potential to unlock transport, especially trucks, as an early adopter of green other feedstocks for biomethane production such as waste gases and as a key enabler of the transition. -

The Future of Gasification

STRATEGIC ANALYSIS The Future of Gasification By DeLome Fair coal gasification projects in the U.S. then slowed significantly, President and Chief Executive Officer, with the exception of a few that were far enough along in Synthesis Energy Systems, Inc. development to avoid being cancelled. However, during this time period and on into the early 2010s, China continued to build a large number of coal-to-chemicals projects, beginning first with ammonia, and then moving on to methanol, olefins, asification technology has experienced periods of both and a variety of other products. China’s use of coal gasification high and low growth, driven by energy and chemical technology today is by far the largest of any country. China markets and geopolitical forces, since introduced into G rapidly grew its use of coal gasification technology to feed its commercial-scale operation several decades ago. The first industrialization-driven demand for chemicals. However, as large-scale commercial application of coal gasification was China’s GDP growth has slowed, the world’s largest and most in South Africa in 1955 for the production of coal-to-liquids. consistent market for coal gasification technology has begun During the 1970s development of coal gasification was pro- to slow new builds. pelled in the U.S. by the energy crisis, which created a political climate for the country to be less reliant on foreign oil by converting domestic coal into alternative energy options. Further growth of commercial-scale coal gasification began in “Market forces in high-growth the early 1980s in the U.S., Europe, Japan, and China in the coal-to-chemicals market. -

Low Carbon Renewable Natural Gas (RNG) from Wood Wastes Site Specific Engineering Design Study

Low Carbon Renewable Natural Gas (RNG) from Wood Wastes Site Specific Engineering Design Study Daniel LeFevers Director, State and Consumer Programs October, 2018 [email protected] - 847-544-3458 Project Background > The Low Carbon RNG from Wood Wastes Engineering Design Study leveraged millions of dollars of previous pilot-scale testing funded by GTI, UPM, Andritz, USDOE, Haldor Topsoe, Pall Corporation, and design work sponsored by European Commission and E.ON. > Funding support for project was provided by California Air Resources Board, Southern California Gas, Pacific Gas and Electric, Northwest Natural and Sacramento Municipal Utility District > RNG technology team members are world experts in gasification, gas clean-up, and conversion technologies. > RNG technology suite is commercially available, with performance guarantees. > Project determined CAPEX and OPEX (+/- 30%) to produce 3 BCF of RNG from wood waste annually. ─ Other project configurations that include power-to-gas and carbon sequestration were analyzed for carbon intensity of RNG produced, additional equipment cost and increase in RNG production up to 7.3 BCF > Goal of project is to provide critical information required to build a commercial facility 2 Special Thanks to the Sponsors of the Project SoCalGas PG&E Northwest Natural SMUD CARB 3 Special Thanks to Our Project Partners and Host Site Black & Veatch Leading global engineering & construction firm - 10,500 employees worldwide ANDRITZ Global supplier of equipment and services including gasification -

Technical Procedures for Using Synthetic Natural Gas As an Alternative to Natural Gas in Different Supply Conditions for Industrial Customers

BRAZILIAN JOURNAL OF PETROLEUM AND GAS | v. 9 n. 2 | p. 037-044 | 2015 | ISSN 1982-0593 TECHNICAL PROCEDURES FOR USING SYNTHETIC NATURAL GAS AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO NATURAL GAS IN DIFFERENT SUPPLY CONDITIONS FOR INDUSTRIAL CUSTOMERS a a a a 1 Costa, F. C.; Moutinho dos Santos, E.; Fagá, M. T. W.; Costa, H. K. M. a Institute of Energy and Environment, Post Graduate Energy Program, University of São Paulo, São Paulo – SP, Brazil ABSTRACT The Synthetic Natural Gas (SNG), as considered in this work, is a blend of Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) and air used to replace Natural Gas (NG). This paper describes different strategies for using SNG as an effective substitute of NG in base-load, backup, and peak-shaving supply conditions to overcome NG supply interruptions from Local Distribution Companies (LDCs) for industrial consumers. The replacement of NG by SNG for industrial uses must deal with technical difficulties, which do not always allow both gases to be immediately exchangeable. The authors point out some of the difficulties involved in the process and propose ways to overcome them during a gas replacement process. KEYWORDS Synthetic Natural Gas; Liquefied Petroleum Gas; propane-air blend; gas replacement; gas exchangeability 1 To whom all correspondence should be addressed. Address: University of São Paulo, Institute of Energy and Environment, Post Graduate Energy Program, Avenida Professor Luciano Gualberto, 1289 - Cidade Universitária, Butantã, São Paulo - SP, Brazil. ZIP Code: 05508-010 | Phone (office): +55(11)3091-2630 |e-mail: [email protected] doi:10.5419/bjpg2015-0005 37 BRAZILIAN JOURNAL OF PETROLEUM AND GAS | v. -

Natural Gas Market Study

Natural Gas Market Study Douglas J. Gotham David G. Nderitu Juan S. Giraldo Paul V. Preckel State Utility Forecasting Group November 2013 Executive Summary The rapid increase in shale gas production in the last decade profoundly affected the U.S. natural gas industry. This report examines the various factors affecting the natural gas industry, including supply, prices, demand, and the risk factors that could significantly affect natural gas prices in the future. The report is done in fulfillment of Indiana Senate Enrolled Act 494 (2013) that directs the Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission to (1) conduct a study of the natural gas market, including: (A) natural gas prices on both the open and captive markets; and (B) the effect of the availability of substitute natural gas and shale gas on natural gas prices (A) Natural gas prices on both the open and captive markets1 The period of time from 2000 through 2008 is characterized by both high average prices and shorter instances of extremely high prices. The price spikes of the winter of 2000/2001 and February 2003 resulted from a combination of low natural gas storage levels and high demand from cold weather. The price spikes of 2006 and 2008 were associated with supply disruptions in the Gulf of Mexico due to hurricane activity. The average price of natural gas dropped considerably in the latter half of 2008 and has stayed low since. The mean Henry Hub spot price for 1997-2008 was $5.09 per million British Thermal Units (mmBtu), while it was only $3.75/mmBtu from 2009 through October 18, 2013. -

Energy & Power – Biofuels: Renewable Natural Gas Stifel Equity

Energy & Power – Biofuels: Renewable Natural Gas A game-changer in the race for net-zero Stifel Equity Research | March 8, 2021 Stifel does and seeks to do business with companies covered in its research reports. As a result, investors should be aware that the firm may have a conflict of interest that could affect the objectivity of this report. Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in their investment decision. All relevant risks, disclosures and certifications appear on pages 58-61 of this report. Key contacts Derrick Whitfield Energy & Power – E&P and Biofuels Managing Director, Stifel Equity Research (214) 706-9451 [email protected] John Annis, CPA Energy & Power – E&P and Biofuels Associate Analyst, Stifel Equity Research (214) 647-3528 [email protected] Billy Howell Energy & Power – E&P and Biofuels Associate Analyst, Stifel Equity Research (713) 237-4531 [email protected] Nate Pendleton, CFA Energy & Power – E&P and Biofuels Associate Analyst, Stifel Equity Research (214) 706-9457 [email protected] Stifel | Renewable Natural Gas 2 Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 7 RNG Overview ............................................................................................................................................................. -

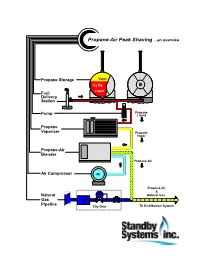

Propane Peak Shaving Systems...An Overview

Propane-Air Peak Shaving ...an overview Propane Storage Vapor C3 H8 Liquid Fuel Delivery Station Propane Pump Liquid Propane Vaporizer Propane Vapor Propane-Air Blender Propane-Air Air Compressor Air Propane-Air & Natural Natural Gas Gas Pipeline City Gate To Distribution System ...about Standby Systems, Inc. Standby Systems, Inc. is a total resource for propane peak shaving and standby systems. We provide a full range of engineering, equipment, construction and customer support. Since 1975, we've been serving needs of natural gas utilities and energy consumers, including: • natural gas “city-gate” systems for heating, metering and control; • industrial / commercial gas distribution systems, process burners and safety audits; • SCADA and other control, communications, safety systems and software; • metering for gas, electric, water and steam systems; • training for operators, technicians and facility managers. We hope you find Propane-Air Peak Shaving ...an overview informative. 1313 PLYMOUTH AVENUE NORTH MINNEAPOLIS, MINNESOTA 55411-4065 USA PHONE 612.721.4473 FAX 612.724.8434 WEB WWW.standby.com EMAIL [email protected] STANDBY SYSTEMS, INC. MAKES NO WARRANTY OF ANY KIND WITH REGARD TO THIS DOCUMENT, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. Standby Systems, Inc. shall not be held liable for errors contained herein or for incidental or consequential damages or loss in connection with the furnishing, use or accuracy of this document. All information contained herein is subject to change without notice. This document contains proprietary information that is protected by copyright. All rights are reserved. No part of this document may be photocopied or reproduced by any other means without the prior written consent of Standby Systems, Inc. -

Synthetic Natural Gas (SNG) from Biomass Synthetic Natural Gas (SNG) from Biomass

Synthetic Natural Gas (SNG) from biomass Synthetic Natural Gas (SNG) from biomass The potential & implementation of SNG by gasification of biomass Ir. Robin Zwart, Dr. Luc Rabou Energy research Centre of the Netherlands (ECN) ECN Biomass, Coal & Environmental Research Content • Introduction on ECN • Definitions • Motivation for Green Natural Gas • Potential & application • Green Natural Gas & SNG implementation • Biomass availability and import • Economy of SNG production • SNG development trajectory • Conclusions (3) ECN–BKM, Robin Zwart Biogas Markets, 30-31 October 2006, Vienna www.ecn.nl Energy research Centre of the Netherlands In the dunes of North Holland • Independent energy research institute • Founded in 1955 • 650 staff • Annual turnover: 80 M€ • Activities: - Biomass, Coal & Environmental Research - Solar - Wind - Hydrogen & Clean Fossil Fuels - Energy Efficiency in the Industry - Energy in the Built Environment - Policy Studies (4) ECN–BKM, Robin Zwart Biogas Markets, 30-31 October 2006, Vienna www.ecn.nl ECN in a glance Mission • ECN is the largest, independent, market oriented, and innovative Dutch energy research institute. • ECN focuses on the knowledge and information the government needs to develop and evaluate policy and achieve policy objectives in the field of energy, the environment and technological innovation. • ECN partners industry in the development and implementation of products, processes and technologies important to the transition to sustainable energy management. • ECN closely works together with Dutch -

Contribution of LNG Use for the Low Calorific Natural Gas Network's

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Energy Procedia 64 ( 2015 ) 83 – 90 3rd Trondheim Gas Technology Conference, TGTC-3 Contribution of LNG use for the low calorific natural gas network’s safe and sustainable operation Dipl.-Ing. Alexey Mozgovoy, Dipl.-Ing. Frank Burmeister, Dr.-Ing. Rolf Albus Gas- und Wärme-Institut Essen e. V., Hafenstrasse 101, Essen 45356, Germany Abstract This paper provides an overview of challenges which are being faced by the German industry, especially by its gas sector. It focuses on the feasibility of the use of liquefied natural gas (further referred to as LNG) in the German natural gas networks in order to substitute natural gas from some sources being depleted. The paper highlights technical requirements which must be matched to allow the injection of LNG into the German natural gas networks. Technical efforts to prepare LNG from different sources are calculated and shown below. © 20152014 The The Authors. Authors. Published Published by byElsevier Elsevier Ltd. Ltd This. is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Peer-review under responsibility of the Scientific Committee of TGTC-3. Peer-review under responsibility of the Scientific Committee of TGTC-3 Keywords: natural gas quality, LNG quality, LNG ballasting, gas market conversion, gas nozzle replacement 1. Introduction The gas supply situation in Germany is determined mostly by domestic gas production as well as by imports from abroad. The main gas import countries are as follows: Russia, Norway and the Netherlands. Compared to the natural gases imported from Russia and Norway the natural gases produced in Germany and imported from the Netherlands are low calorific (further referred to as L-gas). -

The Potential to Build Current Natural Gas Infrastructure to Accommodate the Future Conversion to Near-Zero Transportation Technology

Research Report – UCD-ITS-RR-17-04 The Potential to Build Current Natural Gas Infrastructure to Accommodate the Future Conversion to Near-Zero Transportation Technology March 2017 Amy Myers Jaffe Rosa Dominguez-Faus Joan Ogden Nathan C. Parker Daniel Scheitrum Zane McDonald, Yueyue Fan Tom Durbin George Karavalakis Justin Wilcock Marshall Miller Christopher Yang Institute of Transportation Studies ◦ University of California, Davis 1605 Tilia Street ◦ Davis, California 95616 PHONE (530) 752-6548 ◦ FAX (530) 752-6572 www.its.ucdavis.edu FINAL REPORT March 24, 2017 The Potential to Build Current Natural Gas Infrastructure to Accommodate the Future Conversion to Near-Zero Transportation Technology Contract No. 14-317 Amy Myers Jaffe, Principal Investigator STEPS Program, Institute of Transportation Studies, UC Davis Disclaimer The statements and conclusions in this Report are those of the contractor and not necessarily those of the California Air Resources Board. The mention of commercial products, their source, or their use in connection with material reported herein is not to be construed as actual or implied endorsement of such products. This Report was submitted in fulfillment of contract 13-307, “The Feasibility of Renewable Natural Gas as a Large-Scale, Low Carbon Substitute” by the STEPS Program, Institute of Transportation Studies, UC Davis under the sponsorship of the California Air Resources Board. Work was completed as of February 29, 2016 and updated as of March 2017. ii Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank our colleagues in research of alternative fuels and vehicles and more sustainable transportation at the California Air Resources Board for funding this contract and the staff with whom we engaged in the Research Division.