Archaeopress Open Access

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comments on the Proposed Boundary Changes to South-East

Comments on the proposed boundary changes to south‐east Oxford As the Chair of Rose Hill and Iffley Low Carbon Community Group, I would argue that the proposed changes make little sense and that the existing ward boundaries should be retained, with the leeway for change mentioned below. Councillors should represent communities, not raw numbers. The natural boundaries of our ward (Rose Hill and Iffley) are the river, ring‐road, Rose Hill/Henley Avenue and Donnington Recreation Ground ‐ or Donnington Bridge Road if a greater number of residents is needed. If a lower number of residents is needed, the area around Westbury Crescent could be moved into Cowley ward as most people regard it as Cowley. We should keep all the houses on both sides of Rose Hill (the road) as it wouldn't make sense to live on Rose Hill and not in it! Our group would be badly affected by the proposed boundary change as we based our choice of name on the fact that they constitute one ward. We have active members in both Rose Hill and Iffley and this helps to bring the two communities together. It has always been helpful to ask known Councillors to represent us on key issues and to build a working relationship with them. It would be very complicated if we had to refer to multiple Councillors in a number of different communities. Rose Hill and Iffley share common resources ‐ the river, the church, Iffley Meadows, the No 3 bus into the town centre, the allotments, the recreation ground and now Rose Hill Community Centre, which provides facilities such as the gym to the whole community. -

11 Witney - Hanborough - Oxford

11 Witney - Hanborough - Oxford Mondays to Saturdays notes M-F M-F S M-F M-F Witney Market Square stop C 06.14 06.45 07.45 - 09.10 10.10 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 15.15 16.20 - Madley Park Co-op 06.21 06.52 07.52 - - North Leigh Masons Arms 06.27 06.58 07.58 - 09.18 10.18 11.23 12.23 13.23 14.23 15.23 16.28 17.30 Freeland Broadmarsh Lane 06.35 07.06 08.07 07.52 09.27 10.27 11.32 12.32 13.32 14.32 15.32 16.37 17.40 Long Hanborough New Road 06.40 07.11 08.11 07.57 09.31 10.31 11.36 12.36 13.36 14.36 15.36 16.41 Eynsham Spareacre Lane 06.49 07.21 08.20 09.40 10.40 11.45 12.45 13.45 14.45 15.45 16.50 Eynsham Church 06.53 07.26 08.24 08.11 09.44 10.44 11.49 12.49 13.49 14.49 15.49 16.54 17.49 Botley Elms Parade 07.06 07.42 08.33 08.27 09.53 10.53 11.58 12.58 13.58 14.58 15.58 17.03 18.00 Oxford Castle Street 07.21 08.05 08.47 08.55 10.07 11.07 12.12 13.12 13.12 15.12 16.12 17.17 18.13 notes M-F M-F S M-F M-F S Oxford Castle Street E2 07.25 08.10 09.10 10.15 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 15.15 16.35 16.35 17.35 17.50 Botley Elms Parade 07.34 08.20 09.20 10.25 11.25 12.25 13.25 14.25 15.25 16.45 16.50 17.50 18.00 Eynsham Church 07.43 08.30 09.30 10.35 11.35 12.35 13.35 14.35 15.35 16.55 17.00 18.02 18.10 Eynsham Spareacre Lane 09.34 10.39 11.39 12.39 13.39 14.39 15.39 16.59 17.04 18.06 18.14 Long Hanborough New Road 09.42 10.47 11.47 12.47 13.47 14.47 15.47 17.07 17.12 18.14 18.22 Freeland Broadmarsh Lane 07.51 08.38 09.46 10.51 11.51 12.51 13.51 14.51 15.51 17.11 17.16 18.18 18.26 North Leigh Masons Arms - 08.45 09.55 11.00 12.00 13.00 -

NEWSLETTER Number 75:~Autumn 2019

West Oxford Community Association NEWSLETTER Number 75:~Autumn 2019 We are looking for new and enthusiastic trustees! The whole community centre is run by a few paid employees and a volunteer group of trustees – we are looking for additional trustees to get involved. The management committee meets just six times per year, with sub-committees that focus on specific projects that they are particularly interested in. It’s a great opportunity to be involved in the local community, meet new people, and feel that you are contributing to West Oxford life. The only special qualities needed to support the com- munity centre is enthusiasm and a love of where we live! ................................................... Please email: [email protected] Tom and Vladimira welcome Weekly Updates on you to Tumbling Bay Cafe ! display in the Community Centre Please note - W0T’S new AT Monthly Updates on New Opening community notice Hours WOCC... boards Tuesday - by ‘The Vinyl Cafe’ Sunday and ‘Cartridge 9.00am - 4.00pm World’, or see our Closed Mondays website www.woca.org.uk Contact: [email protected] TO LOCAL MAKERS AND ARTISTS WOCA Christmas Market 2019 Saturday 23 November and Jazz Brunches Sunday 24 November Following roaring The WOCA Christmas Arts and Crafts success with his band Market will be back 2019. on the patio at the Fun Day, Supremo of the Would any local artist or maker who is keys and vocalese Mr interested in taking part- or in finding Nick Gill will be back at out more - please get in touch with the the centre this autumn office at WOCA, ideally by the end of with tall tales of the September? Jazz Age and some swinging grooves to get your toes tapping—all Improvements at WOCC… over Saturday brunch! It’s been a busy summer again at the From 10am on centre, catching up with things after the 19 October Fun Day and making various 16 November improvements including: A complete refurbishing of the Ceilidh female toilets, including installation of changing facilities. -

The Field Names of Cowley.Pdf

The field names of Cowley Christopher Lewis Cowley and its common fields When I refer to ‘Cowley’ I usually mean the area defined by the Enclosure Commissioners in 1853, encompassing all those detached areas of other parishes.1 The common fields of Cowley stretched from the banks of the Cherwell, south-eastwards to the old Roman Road and the borders with Horspath, Littlemore and Iffley, with a small detached portion on the slopes of Shotover Hill, known as Elder Stumps. A brook, now known as Boundary Brook, runs east to west across this area. Originally it meandered across the fields slightly south of its present course, but it was straightened, and probably deepened, at the time of the Enclosure. Our knowledge of the field names, and where they are in the landscape, mostly comes from maps made for Corpus Christi College, Christ Church, and Pembroke College, and then later in a series of Tithe maps and Enclosure maps. Field boundaries, parish boundaries, and roads are not necessarily coincident, and the boundaries of the open fields are not always shown on the maps. The earliest map that shows the borders of the fields was made for Christ Church by William Chapman in 1777 and names the larger fields as Millam, Long Mead, Compass Field, Ridge Field, Bartholomew Field, The Lakes, Cowley Marsh, and Lye Hill all north of the brook, and Wood Field, Fur Field, Broad Field, and Church Field to the south.2 Other names appear in the documents, sometimes as alternative names for the same pieces of ground, and sometimes seeming more important than the names on the Chapman map. -

Settlement Type

Design Guide 5 Settlement Type www.westoxon.gov.uk Design Guide 5: Settlement Type 2 www.westoxon.gov.uk Design Guide 5: Settlement Type 5.1 SETTLEMENT TYPE Others have an enclosed character with only limited views. Open spaces within settlements, The settlements in the District are covered greens, squares, gardens – even wide streets – by Local Plan policies which describe the contribute significantly to the unique form and circumstances in which any development will be character of that settlement. permitted. Most new development will occur in sustainable locations within the towns and Where development is permitted, the character larger villages where a wide range of facilities and and context of the site must be carefully services is already available. considered before design proposals are developed. Fundamental to successfully incorporating change, Settlement character is determined by a complex or integrating new development into an existing series of interactions between it and the landscape settlement, is a comprehensive understanding of in which it is set – including processes of growth the qualities that make each settlement distinctive. or decline through history, patterns of change in the local economy and design or development The following pages represent an analysis of decisions by landowners and residents. existing settlements in the District, looking at the pattern and topographic location of settlements; As a result, the settlements of West Oxfordshire as well as outlining the chief characteristics of all vary greatly in terms of settlement pattern, scale, of the settlements in the District (NB see 5.4 for spaces and building types. Some villages have a guidance on the application of this analysis). -

Badgers - Numbers, Gardens and Public Attitudes in Iffley Fields

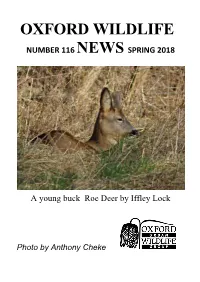

OXFORD WILDLIFE NUMBER 116 NEWS SPRING 2018 A young buck Roe Deer by Iffley Lock Photo by Anthony Cheke NEWS FROM BOUNDARY BROOK NATURE PARK The hedge around the Nature Park between us and the allotment area had grown a lot during the last year and was encroaching on the allotment site. The allotment holders understandably were not happy about this and were prepared to get a professional group to do the work. This would have been very expensive for us and nobody volunteered to help with the clearance. Very nobly Alan Hart, the Warden, made a start on this great task and made tremendous progress. Then the snow came. Alan could not even get into Oxford let alone cut the hedge! He has now done more but there is still a lot to be done if anyone feels willing to help, please contact him. His phone numbers are on the back page of this newsletter. PAST EVENTS Sadly, the January day we chose for our winter walk in University Parks to the river was literally a “wash-out”! On the day, in case the rain decided to stop, I turned up at the meeting place at the time we’d chosen but as I suspected nobody had turned out and the rain didn’t stop. Maybe we could schedule it again. It would be useful if you could let me know if you would have come if the sun had been shining. If not are there any other places in the Oxford area you’d like to explore. Please let me know if so. -

Town and Country Planning Acts Require the Following to Be Advertised 17/01394/FUL BRIZE NORTON DEP CONLB MAJ PROW

WEST OXFORDSHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL Town and Country Planning Acts require the following to be advertised 17/01394/FUL BRIZE NORTON DEP CONLB MAJ PROW. Land South of Upper Haddon Farm Station Road Brize Norton. 17/01441/HHD SHIPTON UNDER WYCHWOOD CONLB PROW. The Old Beerhouse Simons Lane Shipton Under Wychwood. 17/01442/LBC SHIPTON UNDER WYCHWOOD LBC. The Old Beerhouse Simons Lane Shipton Under Wychwood. 17/01453/HHD WOODSTOCK CONLB. 126 Oxford Street Woodstock Oxfordshire. 17/01337/HHD LITTLE TEW CONLB. Manor House Chipping Norton Road Little Tew. 17/01338/LBC LITTLE TEW LBC. Manor House Chipping Norton Road Little Tew. 17/01392/LBC STANDLAKE LBC. Midway Lancott Lane Brighthampton. 17/01395/HHD DUCKLINGTON CONLB. 3 The Square Ducklington Witney. 17/01450/S73 GREAT TEW CONLB. Land at the Great Tew Estate Great Tew Oxfordshire. 17/01482/HHD FULBROOK PROW. Appledore Garnes Lane Fulbrook. 17/01627/HHD HAILEY CONLB PROW. 1 Middletown Cottages Middletown Hailey. 17/01332/HHD BAMPTON PROW. 5 Mercury Court Bampton Oxfordshire. 17/01255/FUL WITNEY CONLB. The Old Coach House Marlborough Lane Witney. 17/01397/FUL ALVESCOT CONLB. Rock Cottage Main Road Alvescot. 17/01406/HHD FILKINS AND BROUGHTON POGGS CONLB. Broctun House Broughton Poggs Lechlade. 17/01399/FUL CHASTLETON CONLB. School Kitebrook House Little Compton. 17/01409/HHD BRIZE NORTON CONLB. Yew Tree Cottage 60 Station Road Brize Norton. 17/01410/LBC BRIZE NORTON LBC. Yew Tree Cottage 60 Station Road Brize Norton. 17/01423/LBC ASCOTT UNDER WYCHWOOD LBC. The Old Farmhouse 15 High Street Ascott Under Wychwood. 17/01214/FUL WITNEY PROW. Cannon Pool Service Station 92 Hailey Road Witney. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

A Brief History of Port Meadow and Wolvercote Common and Picksey Mead, and Why Their Plant Communities Changed Over the Last 90 Years A

A brief history of Port Meadow and Wolvercote Common and Picksey Mead, and why their plant communities changed over the last 90 years A. W McDonald Summary A multidisciplinary approach to landscape history enabled the examination of botanical, hydrological and agricultural data spanning some 4,000 years. The results showed Bronze Age humans affecting the vegetation by pasturing cattle on the floodplain extending from Yarnton to Oxford. In the Iron Age pastoralists were over-grazing Port Meadow and, between the sixth and ninth centuries, part of the floodplain was set aside for a hay crop whilst the aftermath or second grass crop continued to be shared as pasture. By Domesday floodplain meads were the most expensive land recorded in this survey and Port Meadow was established as common land belonging to Oxford. Having discussed the soil and water conditions on the floodplain and its potential effect on the plant communities, the management history of Port Meadow with Wolvercote Common is followed by that of Picksey Mead. Finally, the plant communities are discussed. Those established in 1981/2 are compared with data sets for the early 1920s and for 1996-2006. Changes in the species composition between sites are due to different management regimes and those over time and within sites are attributed to changes in the water-table. Introduction The Oxford grassland comprises common pasture and mead situated on alluvium over limestone gravel. It is unusual for its four thousand years of management history and evidence for the effect this has had on the vegetation. Sited in the upper Thames valley, within three miles of Oxford City centre, Port Meadow (325 acres/132 ha) and Wolvercote Common (75 acres/30.4 ha) (Figure 1 and Figure 2) are known locally as the Meadow, even though they are pasture1. -

Early Medieval Oxfordshire

Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire Sally Crawford and Anne Dodd, December 2007 1. Introduction: nature of the evidence, history of research and the role of material culture Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire has been extremely well served by archaeological research, not least because of coincidence of Oxfordshire’s diverse underlying geology and the presence of the University of Oxford. Successive generations of geologists at Oxford studied and analysed the landscape of Oxfordshire, and in so doing, laid the foundations for the new discipline of archaeology. As early as 1677, geologist Robert Plot had published his The Natural History of Oxfordshire ; William Smith (1769- 1839), who was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire, determined the law of superposition of strata, and in so doing formulated the principles of stratigraphy used by archaeologists and geologists alike; and William Buckland (1784-1856) conducted experimental archaeology on mammoth bones, and recognised the first human prehistoric skeleton. Antiquarian interest in Oxfordshire lead to a number of significant discoveries: John Akerman and Stephen Stone's researches in the gravels at Standlake recorded Anglo-Saxon graves, and Stone also recognised and plotted cropmarks in his local area from the back of his horse (Akerman and Stone 1858; Stone 1859; Brown 1973). Although Oxford did not have an undergraduate degree in Archaeology until the 1990s, the Oxford University Archaeological Society, originally the Oxford University Brass Rubbing Society, was founded in the 1890s, and was responsible for a large number of small but significant excavations in and around Oxfordshire as well as providing a training ground for many British archaeologists. Pioneering work in aerial photography was carried out on the Oxfordshire gravels by Major Allen in the 1930s, and Edwin Thurlow Leeds, based at the Ashmolean Museum, carried out excavations at Sutton Courtenay, identifying Anglo-Saxon settlement in the 1920s, and at Abingdon, identifying a major early Anglo-Saxon cemetery (Leeds 1923, 1927, 1947; Leeds 1936). -

John Buchan's Uncollected Journalism a Critical and Bibliographic Investigation

JOHN BUCHAN’S UNCOLLECTED JOURNALISM A CRITICAL AND BIBLIOGRAPHIC INVESTIGATION PART II CATALOGUE OF BUCHAN’S UNCOLLECTED JOURNALISM PART II CATALOGUE OF BUCHAN’S UNCOLLECTED JOURNALISM Volume One INTRODUCTION............................................................................................. 1 A: LITERATURE AND BOOKS…………………………………………………………………….. 11 B: POETRY AND VERSE…………………………………………………………………………….. 30 C: BIOGRAPHY, MEMOIRS, AND LETTERS………………………………………………… 62 D: HISTORY………………………………………………………………………………………………. 99 E: RELIGION……………………………………………………………………………………………. 126 F: PHILOSOPHY AND SCIENCE………………………………………………………………… 130 G: POLITICS AND SOCIETY……………………………………………………………………… 146 Volume Two H: IMPERIAL AND FOREIGN AFFAIRS……………………………………………………… 178 I: WAR, MILITARY, AND NAVAL AFFAIRS……………………………………………….. 229 J: ECONOMICS, BUSINESS, AND TRADE UNIONS…………………………………… 262 K: EDUCATION……………………………………………………………………………………….. 272 L: THE LAW AND LEGAL CASES………………………………………………………………. 278 M: TRAVEL AND EXPLORATION……………………………………………………………… 283 N: FISHING, HUNTING, MOUNTAINEERING, AND OTHER SPORTS………….. 304 PART II CATALOGUE OF BUCHAN’S UNCOLLECTED JOURNALISM INTRODUCTION This catalogue has been prepared to assist Buchan specialists and other scholars of all levels and interests who are seeking to research his uncollected journalism. It is based on the standard reference work for Buchan scholars, Robert G Blanchard’s The First Editions of John Buchan: A Collector’s Bibliography (1981), which is generally referred to as Blanchard. The catalogue builds on this work -

Oxfordshire Local History News

OXFORDSHIRE LOCAL HISTORY NEWS The Newsletter of the Oxfordshire Local History Association Issue 128 Spring 2014 ISSN 1465-469 Chairman’s Musings gaining not only On the night of 31 March 1974, the inhabitants of the Henley but also south north-western part of the Royal County of Berkshire Buckinghamshire, went to bed as usual. When they awoke the following including High morning, which happened to be April Fools’ Day, they Wycombe, Marlow found themselves in Oxfordshire. It was no joke and, and Slough. forty years later, ‘occupied North Berkshire’ is still firmly part of Oxfordshire. The Royal Commission’s report Today, many of the people who live there have was soon followed by probably forgotten that it was ever part of Berkshire. a Labour government Those under forty years of age, or who moved in after white paper. This the changes, may never have known this. Most broadly accepted the probably don’t care either. But to local historians it is, recommendations of course, important to know about boundaries and apart from deferring a decision on provincial councils. how they have changed and developed. But in the 1970 general election, the Conservatives were elected. Prime Minister Edward Heath appointed The manner in which the 1974 county boundary Peter Walker as the minister responsible for sorting the changes came about is little known but rather matter out. He produced another but very different interesting. Reform of local government had been on white paper. It also deferred a decision on provincial the political agenda since the end of World War II.