World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

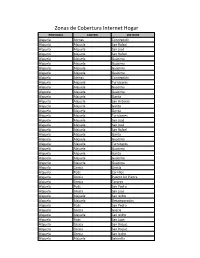

Zonas De Cobertura Internet Hogar

Zonas de Cobertura Internet Hogar PROVINCIA CANTON DISTRITO Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela San Antonio Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Poás Carrillos Alajuela Grecia Puente De Piedra Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia San José Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Desamparados Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Poás San Juan Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Sabanilla Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Grecia Bolivar Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia San Jose Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Tacares -

Nombre Del Comercio Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario

Nombre del Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario comercio Almacén Agrícola Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Cruce Del L-S 7:00am a 6:00 pm Aguas Claras Higuerón Camino A Rio Negro Comercial El Globo Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, contiguo L - S de 8:00 a.m. a 8:00 al Banco Nacional p.m. Librería Fox Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, frente al L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Liceo Aguas Claras p.m. Librería Valverde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 500 norte L-D de 7:00 am-8:30 pm de la Escuela Porfirio Ruiz Navarro Minisúper Asecabri Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Las Brisas L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 6:00 400mts este del templo católico p.m. Minisúper Los Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, Cuatro L-D de 6 am-8 pm Amigos Bocas diagonal a la Escuela Puro Verde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Porvenir L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Supermercado 100mts sur del liceo rural El Porvenir p.m. (Upala) Súper Coco Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 300 mts L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 7:00 norte del Bar Atlántico p.m. MINISUPER RIO Alajuela AGUAS ALAJUELA, UPALA , AGUAS CLARAS, L-S DE 7:00AM A 5:00 PM NIÑO CLARAS CUATRO BOCAS 200M ESTE EL LICEO Abastecedor El Alajuela Aguas Zarcas Alajuela, Aguas Zarcas, 25mts norte del L - D de 8:00 a.m. -

TIBÁS - MORAVIA - GUADALUPE De Autobús

Horario y mapa de la línea INTER URUCA - TIBÁS - MORAVIA - GUADALUPE de autobús Cercanías A Parque INTERLÍNEA URUCA - TIBÁS - M… Guadalupe, Ver En Modo Sitio Web Goicoechea →Terminal La Uruca La línea INTER URUCA - TIBÁS - MORAVIA - GUADALUPE de autobús (Cercanías A Parque Guadalupe, Goicoechea →Terminal La Uruca) tiene 2 rutas. Sus horas de operación los días laborables regulares son: (1) a Cercanías A Parque Guadalupe, Goicoechea →Terminal La Uruca: 5:00 - 18:00 (2) a Terminal La Uruca →Cercanías A Parque Guadalupe, Goicoechea: 5:00 - 19:00 Usa la aplicación Moovit para encontrar la parada de la línea INTER URUCA - TIBÁS - MORAVIA - GUADALUPE de autobús más cercana y descubre cuándo llega la próxima línea INTERLÍNEA URUCA - TIBÁS - MORAVIA - GUADALUPE de autobús Sentido: Cercanías A Parque Guadalupe, Horario de la línea INTER URUCA - TIBÁS - MORAVIA - Goicoechea →Terminal La Uruca GUADALUPE de autobús 30 paradas Cercanías A Parque Guadalupe, Goicoechea →Terminal La VER HORARIO DE LA LÍNEA Uruca Horario de ruta: lunes 5:00 - 18:00 Cercanías A Parque Guadalupe, Goicoechea martes 5:00 - 18:00 Parqueo Almacén Gollo Guadalupe, Goicoechea miércoles 5:00 - 18:00 Calle 63, Costa Rica jueves 5:00 - 18:00 Frente A Multicentro Mig, Guadalupe Goicoechea viernes 5:00 - 18:00 Costado Norte Sykes San Vicente Moravia sábado 5:00 - 18:00 Diagonal 47, Costa Rica domingo 5:00 - 18:00 Costado Sur Iglesia De San Vicente De Moravia Costado Este Supermercado Jumbo, Moravia Calle 63, Costa Rica Información de la línea INTER URUCA - TIBÁS - MORAVIA Liceo Laboratorio -

DESAMPARADOS - GRAVILIAS - VILLA NUEVA De Autobús

Horario y mapa de la línea SAN JOSÉ - DESAMPARADOS - GRAVILIAS - VILLA NUEVA de autobús San José - Desamparados SAN JOSÉ - DESAMPARADOS - … - Gravilias - Ver En Modo Sitio Web Villa Nueva (R:70) La línea SAN JOSÉ - DESAMPARADOS - GRAVILIAS - VILLA NUEVA de autobús (San José - Desamparados - Gravilias - Villa Nueva (R:70)) tiene 2 rutas. Sus horas de operación los días laborables regulares son: (1) a Terminal Riberalta, Plantel De Buses Atd Desamparados →Terminal San José, Cercanías Plaza De Las Garantías Sociales La Soledad: 7:05 - 19:05 (2) a Terminal San José, Cercanías Plaza De Las Garantías Sociales La Soledad →Terminal Riberalta, Frente A Plantel De Buses Atd Desamparados: 5:20 - 19:40 Usa la aplicación Moovit para encontrar la parada de la línea SAN JOSÉ - DESAMPARADOS - GRAVILIAS - VILLA NUEVA de autobús más cercana y descubre cuándo llega la próxima línea SAN JOSÉ - DESAMPARADOS - GRAVILIAS - VILLA NUEVA de autobús Sentido: Terminal Riberalta, Plantel De Buses Atd Horario de la línea SAN JOSÉ - DESAMPARADOS - Desamparados →Terminal San José, Cercanías GRAVILIAS - VILLA NUEVA de autobús Plaza De Las Garantías Sociales La Soledad Terminal Riberalta, Plantel De Buses Atd → 27 paradas Desamparados Terminal San José, Cercanías Plaza VER HORARIO DE LA LÍNEA De Las Garantías Sociales La Soledad Horario de ruta: Terminal Riberalta, Plantel De Buses Atd lunes Sin servicio Desamparados martes Sin servicio Contiguo A Abastecedor Cisne De Orocercanías miércoles Sin servicio Abastecedor Cisne De Oro, Riberalta Desamparados jueves Sin servicio -

Mapa De Vías Provincia 1 San José Cantón 12 Acosta

MAPA DE VÍAS PROVINCIA 1 SAN JOSÉ CANTÓN 12 ACOSTA 465000 470000 475000 480000 485000 Mapa de Vías Provincia 1 San José AlajCuelea ntro Urbano de San Ignacio ESCALA 1 : 5.050 Cantón 12 Acosta 482200 Ministerio de Hacienda l Río a J iz Órgano de Normalización Técnica orc rr o a C Santa Ana a d Escazú 0 ra 0 b 0 e 5 u o 9 z 0 Q la 1 b Ta a ad br ue Proyecto Habitacional de Q Interés Social El Tablazo Cementerio Pollo El Leñador CAIPAD Salón Comunal SAN IGNACIO Plaza de Fútbol Mora San Ignacio l venida 3 a A r t Escuela Cristóbal Colón n Sucursal CCSS nm e C BNCR BCR e l l Parque Central a Gollo C 1 Alajuelita C æ e l Cruz Roja l a a l l Gimnasio e C 0 0 0 1 0 4 A 4 Aprobado por: 3 3 8 8 0 Delegación de Policía 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 9 0 o 1 gr Ne o Ing. Alberto Poveda Alvarado CTP Acosta UNED Acosta Rí nm Director Órgano Normalización Técnica Jaular Río T Pozos abarcia Hogar de Ancianos A Ta 482200 ba R rc ut Q ia a N u ac e io Cañadas b na r l 2 a 0 San PabloBar San Pablo d 9 Palmichal Proyecto Vida Nueva a æ S nmnm CTP Palmichal nm a Salón Comunal nm l to Cedral Charcalillo Fila Calle Valverde Bar Linda Vista A Tarbaca Q Puriscal a u t e i b P Bolívar r a a d d PALMICHAL a a P r a b lm e ic u h Q a l Hacienda Jorco Bajo Cerdas Escuelanm Caragral Escuela Bnmaæjo Cerdas a Sevilla c ra Escuela Sevilla ir nm h a a C n a i n d o M a r M b a ³ e d a u a d r Q a a ill b r rt e b a u e M æ u da Q Lagunmnillas a Q br A Bajos de Jorco e Ta u ba Salón Comunal Q 0 rc nm æ 0 ia Escuela y Colegio Juan Calderón Valverde 0 l a 5 nm iz 8 Bar El Sesteo rr 0 a Q -

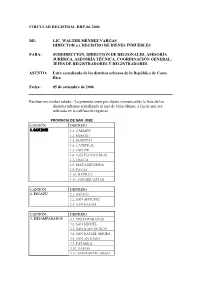

Circular Registral Drp-06-2006

CIRCULAR REGISTRAL DRP-06-2006 DE: LIC. WALTER MÉNDEZ VARGAS DIRECTOR a.i. REGISTRO DE BIENES INMUEBLES PARA: SUBDIRECCIÓN, DIRECCIÓN DE REGIONALES, ASESORÍA JURÍDICA, ASEOSRÍA TÉCNICA, COORDINACIÓN GENERAL, JEFES DE REGISTRADORES Y REGISTRADORES. ASUNTO: Lista actualizada de los distritos urbanos de la República de Costa Rica Fecha: 05 de setiembre de 2006 Reciban mi cordial saludo. La presente tiene por objeto comunicarles la lista de los distritos urbanos actualizada al mes de Julio último, a fin de que sea utilizada en la califiación registral. PROVINCIA DE SAN JOSE CANTÓN DISTRITO 1. SAN JOSE 1.1. CARMEN 1.2. MERCED 1.3. HOSPITAL 1.4. CATEDRAL 1.5. ZAPOTE 1.6. SAN FCO DOS RIOS 1.7. URUCA 1.8. MATA REDONDA 1.9. PAVAS 1.10. HATILLO 1.11. SAN SEBASTIAN CANTÓN DISTRITO 2. ESCAZU 2.1. ESCAZU 2.2. SAN ANTONIO 2.3. SAN RAFAEL CANTÓN DISTRITO 3. DESAMPARADOS 3.1. DESAMPARADOS 3.2. SAN MIGUEL 3.3. SAN JUAN DE DIOS 3.4. SAN RAFAEL ARRIBA 3.5. SAN ANTONIO 3.7. PATARRA 3.10. DAMAS 3.11. SAN RAFAEL ABAJO 3.12. GRAVILIAS CANTÓN DISTRITO 4. PURISCAL 4.1. SANTIAGO CANTÓN DISTRITO 5. TARRAZU 5.1. SAN MARCOS CANTÓN DISTRITO 6. ASERRI 6.1. ASERRI 6.2. TARBACA (PRAGA) 6.3. VUELTA JORCO 6.4. SAN GABRIEL 6.5.LEGUA 6.6. MONTERREY CANTÓN DISTRITO 7. MORA 7.1 COLON CANTÓN DISTRITO 8. GOICOECHEA 8.1.GUADALUPE 8.2. SAN FRANCISCO 8.3. CALLE BLANCOS 8.4. MATA PLATANO 8.5. IPIS 8.6. RANCHO REDONDO CANTÓN DISTRITO 9. -

Reporte Comercios Participantes MK

COMERCIO PARTICIPANTE PROVINCIA DIRECCIÓN TELÉFONO CENTRO DE MATERIALES LA MARINA ALAJUELA 200N,DEL INA BO.LA MARINA LA PALMERA LOC.M.D.VERDE SAN CARLOS,ALAJUELA. 24743614 SERVICIOS DE PINTURA BLANDON LIMON COST.O.MAXIPALI,LOC.MI.COLINA,LIMON. 27587465 FERRETERIA VALLEJO HEREDIA HEREDIA AURORA 300 N TANQUES DE AGUA 22937374 FERRESOLUCIONES SAN JOSE SAN JOSE 100 S.CASA ITALIA 22252722 RODIOS CARTAGO 50 O.GRAVILIAS,MI.PALMAS,OCCI DENTAL,CARTAGO. 88860643 FERRETERIA PACHECO Y VARGAS CARTAGO 50S.CRUCE AGUA CALIENTE,LOC.MDBO PITAHAYA,OCCIDENTAL,CARTAGO 25523423 ALMACEN EL MEJOR PRECIO LIMON 200 N.BCO.NAC.CARIARI POCOCILIMON. 27677015 ALMACEN FERRETERIA 3 R LIMON 20 E,SERVI REPUESTOS GUAPILESPOCOCI,LIMON. 27103907 FERRETERIA CARRANZA ALAJUELA FTE.MERCADO MUNICIP.LOS CHILESLOC.COLOR GRIS,LOS CHILES CTROALAJUELA. 24710033 INDUNI ALMACEN ELECTRICO ALAJUELA 500 mts norte de tribunales de Justicia, Carretera a tuetal 24451590 FERRETERIA BLANDON LIMON GUACIMO CTRO.LOC.1,CC.TERMINAL DE BUSES GUACIMO,50 E.50 S.CLINICA CCSS,1ER PISO,MD.LIMON. 27166942 MATERIALES SAN CARLOS ALAJUELA 50 O.GUACAMAYA,CIUDAD QUESADASAN CARLOS,ALAJUELA. 24607922 IMPORTACIONES PURISCAL SAN JOSE 100S,25 O,DE CASA CURAL PURIS CAL,BO.CTRO.DEL DISTRITO SAN TIAGO DE PURISCAL,SAN JOSE. 24166340 FERRETERIA JACO PUNTARENAS 600 E,POPS,M.D,LOCAL BLANCO,PUJACO,GARABITO,B CTR DISTR PUNTARENAS 26433260 FERRETERIA WM SUAREZ ALAJUELA 150 O,25 S,IGLESIA RINCON ZARAGOZA,PALMARES,M/D,BLA NCO,ALAJUELA. 24532355 ROBERTO VARGAS E HIJO ALAJUELA COST.N.MERCADO MUNICIPAL ATENA S,ATENAS,ALAJUELA. 24468585 FERRETERIA SEGURA SAN JOSE 200 mts oeste Perimercado Vargas Araya 22534010 FERRETERIA EL ANGEL CARTAGO PARAISO 200S.25E.ESTADIO MUNI CIPAL,PARAISO CARTAGO. -

Sucursales Correos De Costa Rica

SUCURSALES CORREOS DE COSTA RICA Oficina Código Dirección Sector 27 de Abril 5153 Costado sur de la Plaza. Guanacaste, Santa Cruz, Veintisiete de Abril. 50303 Resto del País Acosta 1500 Costado Este de la Iglesia Católica, contiguo a Guardia de Asistencia Rural, San GAM Ignacio, Acosta, San José 11201 Central 1000 Frente Club Unión. San José, San Jose, Merced. 10102 GAM Aguas Zarcas 4433 De la Iglesia Católica, 100 metros este y 25 metros sur. Alajuela, San Carlos, Resto del País Aguas Zarcas. 21004 Alajuela 4050 Calle 5 Avenida 1. Alajuela, Alajuela. 20101 GAM Alajuelita 1400 De la iglesia Católica 25 metros al sur San José, Alajuelita, Alajuelita. 11001 GAM Asamblea 1013 Edificio Central Asamblea Legislativa San José, San Jose, Carmen. 10101 GAM Legislativa Aserrí 1450 Del Liceo de Aserrí, 50 metros al norte. San José, Aserrí, Aserrí. 10601 GAM Atenas 4013 De la esquina sureste de el Mercado, 30 metros este. Alajuela, Atenas, Atenas. Resto del País 20501 Bagaces 5750 Contiguo a la Guardia de Asistencia Rural. Guanacaste, Bagaces, Bagaces. Resto del País 50401 Barranca 5450 Frente a Bodegas de Incoop. Puntarenas, Puntarenas, Barranca. 60108 Resto del País Barrio México 1005 De la plaza de deportes 50 metros norte y 25 metros este, San José, San José, GAM Merced. 10102 Barrio San José de 4030 De la iglesia Católica, 200 metros oeste. Alajuela, Alajuela , San José. 20102 GAM Alajuela Barva de Heredia 3011 Calle 4, Avenida 6. Heredia, Barva, Barva. 40201 GAM Bataán 7251 Frente a la parada de Buses. Limón, Matina, Batan. 70502 Resto del País Boca de Arenal 4407 De la Iglesia Católica, 200 metros sur. -

Reporte Epidemiológico Del Covid-19 Al 18 De Mayo 2021

UNIVERSIDAD DE COSTA RICA Proyecto: 748-C0-245 “Análisis y simulación espacial de la Pandemia Covid-19 a nivel cantonal, para el caso de Costa Rica, Observatorio del Desarrollo-UCR”. Elaborado por: MSI. Agustín Gómez Meléndez Estudiantes: Antonieta Avalos Salas (Geografía) María Jesús Mora Vásquez (Estadística) Valeria Alvarado Madrigal (Estadística) Nayelli Barquero Ramírez (Estadística) El Observatorio del Desarrollo (OdD) reúne, organiza e interpreta la dinámica de los casos de la enfermedad COVID-19 en Costa Rica a partir de la información oficial suministrada por el Ministerio de Salud. El presente informe se centra en los días del 12 al 18 de mayo del 2021. En los últimos 7 días, del 12 al 18 de mayo, Costa Rica acumuló un total de 17 206 casos nuevos de Covid-19, de los cuales 14 064 fueron diagnosticados por prueba y 3 142 por nexo epidemiológico. En comparación con los 7 días previos, se presentó un crecimiento de 1 472 casos, es decir, un 9% más de casos nuevos. El promedio de casos diarios pasó de 2 247 a 2 458 para esta semana. Evolución de los casos darios de Covid-19 para Costa Rica y promedio movil cada 7 días y la tasa de reproducibildiad (R_t) 3500 2 1,8 3000 1,6 2500 1,4 1,2 2000 1 1500 0,8 1000 0,6 0,4 500 0,2 0 0 44280 44290 44300 44310 44320 44330 44340 Casos diarios Promedio Movil RT Si se analiza el comportamiento mensual del Covid-19, al final de marzo se reportaron 217 346 casos y al final de abril 250 991, es decir, el incremento fue de un 15,5%. -

LA GACETA N° 274 De La Fecha 17 11 2020

La Uruca, San José, Costa Rica, martes 17 de noviembre del 2020 AÑO CXLII Nº 274 76 páginas Pág 2 La Gaceta Nº 274 — Martes 17 de noviembre del 2020 son: Diario, Mayor y Balances, todos del tomo número dos. Se CONTENIDO emplaza por ocho días hábiles a partir de la publicación a cualquier interesado a fin de oír objeciones ante el Registro de Asociaciones.— Pág Diez de noviembre del 2020.—Francini Araya Arrieta, Presidente y N° Representante Legal.—1 vez.—( IN2020501056 ). FE DE ERRATAS ..................................................... 2 ZUSOME S. A. PODER EJECUTIVO La señora Ana Zulay Soto, en calidad de apoderada de la empresa: Directriz ................................................................... 2 Zusome S. A., cédula jurídica N° 3-103-105527, solicita al Registro Acuerdos .................................................................. 3 Nacional, se rectifique en la base de datos su nombre correcto: Ana Zulay Soto Méndez y no: “Ana Zalay”, como por error material se DOCUMENTOS VARIOS........................................ 7 consignó en la constitución de la sociedad que representa. Escritura TRIBUNAL SUPREMO DE ELECCIONES N° 145, otorgada ante la notaría de la Licda. Jacqueline Villalobos Resoluciones .......................................................... 36 Durán.—San José, 12 de noviembre del 2020.—Licda. Jacqueline Villalobos Durán, Notaria.—1 vez.—( IN2020501110 ). Avisos ..................................................................... 36 CONTRATACIÓN ADMINISTRATIVA .............. 37 PODER EJECUTIVO REGLAMENTOS -

Listado De Centros Educativos Donde No Se Impartirán Lecciones Del 16 Al

Listado de centros educativos donde no se impartirán lecciones Del 16 al 29 de marzo del 2020 Según resoluciones MEP-0530-2020 y MEP-0531-2020 Actualizado el domingo 15 de marzo de 2020 a las 2:55 p.m. # Provincia Cantón Distrito Dirección Regional Circuito Nombre del Centro Educativo Código 1 Alajuela Alajuela Alajuela DRE Alajuela 1 ENSEÑANZA ESPECIAL Y REHABILITACION ALAJUELA 4439 2 Alajuela Grecia Grecia DRE Alajuela 6 ENSEÑANZA ESPECIAL DE GRECIA 4440 3 Alajuela San Carlos Quesada DRE San Carlos 14 ENSEÑANZA ESPECIAL AMANDA ALVAREZ DE UGALDE 4514 4 Alajuela San Ramón San Ramón DRE Occidente 1 ENSEÑANZA ESPECIAL Y REHABILITACION DE SAN RAMÓN 4495 5 Cartago Cartago Carmen DRE Cartago 1 DR CARLOS SAENZ HERRERA 4535 6 Cartago La Unión Río Azul DRE Desamparados 1 FRANCISCO GAMBOA MORA 548 7 Cartago La Unión Río Azul DRE Desamparados 1 LINDA VISTA 476 8 Cartago La Unión San Diego DRE Cartago 6 CALLE GIRALES 1917 9 Cartago La Unión San Diego DRE Cartago 6 CALLE MESÉN 1726 10 Cartago La Unión San Diego DRE Cartago 6 LICEO SAN DIEGO 4059 11 Cartago La Unión San Diego DRE Cartago 6 SAN DIEGO 1871 12 Cartago La Unión San Diego DRE Cartago 6 SANTIAGO DEL MONTE 1900 13 Cartago La Unión San Diego DRE Cartago 6 UNIDAD PEDAGÓGICA SAN DIEGO 5834 14 Cartago La Unión San Juan DRE Cartago 6 MARÍA AMELIA MONTEALEGRE 1880 15 Cartago La Unión San Juan DRE Cartago 6 VILLAS DE AYARCO 1728 16 Cartago La Unión San Rafael DRE Cartago 6 CAROLINA BELLELLI DE M. -

San Jose Nos Mueve

PLAN DE GOBIERNO MUNICIPAL 2020-2024 SAN JOSE NOS MUEVE INDICE 1.- Introducción. 2.- Integrantes a Candidatos a Regidores y Síndicos. 3.- Diagnóstico situacional del Cantón Central de San José. 4.- Ejes Rectores de nuestra propuesta para el Cantón. a) San José con futuro Próspero. b) San José con futuro Sustentable. c) San José con futuro Incluyente. d) San José con futuro Seguro. e) San José con futuro Funcional. f) San José con futuro Innovador. 5.- Etapas de Planeación del Futuro Programa Desarrollo Municipal y puntos críticos. 6.-Principios administración municipal 2020-2024. 7.-Diseño, formulación, participación ciudadana, análisis, aprobación, ejecución, control y seguimiento del Plan a Ejecutar Municipal, 2020-2024. 8.- Programas sectoriales por eje rector. 9.- Agradecimientos. 10.- Referencias bibliográficas y fuentes consultadas. Mensaje del Candidato Alcalde Estimados ( as ) habitantes del Cantón Central de San José: El Partido Nuestro Pueblo, lo conforman un grupo de ciudadanos identificados con el cambio por un San José, más verde, ecológico, seguro y democrático. En este tiempo de crisis cantonal, nacional y de falta de liderazgo, me han honrado con la designación, de ser su candidato a la Alcaldía Municipal de San José, (2020-2024). Candidatura que asumo con mucha humildad, pero motivado en construir “Una ciudad de San José mejor ”, con mayor vida cultural, más espacios públicos seguros, y áreas verdes que sean de nuestra pertenencia y que a su vez sean puntos de encuentro e intercambio vecinal, un sistema vial que dé prioridad al peatón, al transporte público moderno y seguro, con la debida atención a niños y adultos mayores,así como grupos vulnerables y con mayores estímulos a la iniciativa de empresas privadas familiares, micro y pequeñas.